From Black Slaves to Black Star

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Autoethnography of Scottish Hip-Hop: Identity, Locality, Outsiderdom and Social Commentary

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Napier An autoethnography of Scottish hip-hop: identity, locality, outsiderdom and social commentary Dave Hook A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Edinburgh Napier University, for the award of Doctor of Philosophy June 2018 Declaration This critical appraisal is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. It has not been previously submitted, in part or whole, to any university or institution for any degree, diploma, or other qualification. Signed:_________________________________________________________ Date:______5th June 2018 ________________________________________ Dave Hook BA PGCert FHEA Edinburgh i Abstract The published works that form the basis of this PhD are a selection of hip-hop songs written over a period of six years between 2010 and 2015. The lyrics for these pieces are all written by the author and performed with hip-hop group Stanley Odd. The songs have been recorded and commercially released by a number of independent record labels (Circular Records, Handsome Tramp Records and A Modern Way Recordings) with worldwide digital distribution licensed to Fine Tunes, and physical sales through Proper Music Distribution. Considering the poetics of Scottish hip-hop, the accompanying critical reflection is an autoethnographic study, focused on rap lyricism, identity and performance. The significance of the writing lies in how the pieces collectively explore notions of identity, ‘outsiderdom’, politics and society in a Scottish context. Further to this, the pieces are noteworthy in their interpretation of US hip-hop frameworks and structures, adapted and reworked through Scottish culture, dialect and perspective. -

Tom Jennings

12 | VARIANT 30 | WINTER 2007 Rebel Poets Reloaded Tom Jennings On April 4th this year, nationally-syndicated Notes US radio shock-jock Don Imus had a good laugh 1. Despite the plague of reactionary cockroaches crawling trading misogynist racial slurs about the Rutgers from the woodwork in his support – see the detailed University women’s basketball team – par for the account of the affair given by Ishmael Reed, ‘Imus Said Publicly What Many Media Elites Say Privately: How course, perhaps, for such malicious specimens paid Imus’ Media Collaborators Almost Rescued Their Chief’, to foster ratings through prejudicial hatred at the CounterPunch, 24 April, 2007. expense of the powerless and anyone to the left of 2. Not quite explicitly ‘by any means necessary’, though Genghis Khan. This time, though, a massive outcry censorship was obviously a subtext; whereas dealing spearheaded by the lofty liberal guardians of with the material conditions of dispossessed groups public taste left him fired a week later by CBS.1 So whose cultures include such forms of expression was not – as in the regular UK correlations between youth far, so Jade Goody – except that Imus’ whinge that music and crime in misguided but ominous anti-sociality he only parroted the language and attitudes of bandwagons. Adisa Banjoko succinctly highlights the commercial rap music was taken up and validated perspectival chasm between the US civil rights and by all sides of the argument. In a twinkle of the hip-hop generations, dismissing the focus on the use of language in ‘NAACP: Is That All You Got?’ (www.daveyd. -

Apollo Theater Announces Details of 2017 Winter/Spring Programs

APOLLO THEATER ANNOUNCES DETAILS OF 2017 WINTER/SPRING PROGRAMS The Apollo Theater Presents AFROPUNK Unapologetically Black: The African American Songbook Remixed A Celebration of Black Protest Music Creative and Musical Direction by Robert Glasper Featuring special guests Jill Scott, Bilal, Toshi Reagon and Staceyann Chin Saturday, February 25th, -7:30 p.m. Africa Now! Presented in Partnership with the World Music Institute Highlighting the Best of the African Music Scene Featuring Musical Force Mbongwana Star, desert punk / blues band, Songhoy Blues, Vocal Powerhouse Lura & House/Afropunk Sensation DJ Nenim Saturday, March 11th, - 8:00 p.m. The Return of WOW – The Apollo Theater presents Southbank Centre London’s WOW - Women of the World Festival A John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Production with Special Guests Esperanza Spalding and Dee Dee Bridgewater Under the musical direction of Terri Lyne Carrington Bringing Together Women Artists, Activists, and Leaders from Around the Globe Featuring an Evening with The Moth and a Tribute to Legendary Songstress Abbey Lincoln Thursday May 4th - Sunday May 7th The Return of the Theater’s Signature Programs Apollo Music Café, Apollo Comedy Club, Amateur Night at the Apollo, and Apollo Uptown Hall As well as ongoing Education and Community Outreach Programs (Harlem, NY – January 18, 2017) – The Apollo Theater today announced additional details for the Winter/Spring programs as part of its 2017 season. The new schedule includes a slate of dynamic programming encompassing festivals, and collaborations with artists and world class arts organizations as well as a wide array of thought-provoking and socially engaging community forums and a host a of education programs for students, young professionals and families. -

Unraveling Native Son: Propagating Communism) Racial Hatred) Societal Change Or None of the Above??

IUSB Graduate Journal Ill 1 Unraveling Native Son: Propagating Communism) Racial Hatred) Societal Change or None of the Above?? by:jacqueline Becker Department of English ABSTRACT: This paper explores the many different ways in which Communism is portrayed within Richard Wright's novel Native Son. It also seeks to illustrate that regardless of the reasoning behind the conflicted portrayal of Communism, within the text, it does serve a vital purpose, and that is to illustrate to the reader that there is no easy answer or solution for the problems facing society. Bigger and his actions cannot be simply dismissed as a product of a damaged society, nor can Communism be seen as an all-encompassing saving grace that will fix all of societies woes. Instead, this novel, seeks to illustrate the type of people that can be produced in a society divided by racial class lines. It shows what can happen when one oppressed group feels as though they have no power over their own lives. I have attempted to illustrate that what Wright ultimately achieved, through his novel Native Son, is to illuminate to readers of the time that a serious problem existed within their society, specifically in Chicago within the "Black Belt" and that the solution lies not with one social group or political party, not through senseless violence, but rather through changes in policy. ~Research~ 2 lll Jacqueline Becker Unraveling Native Son: Propagating Communism) Racial Hatred) Societal Change or None of the Above?? ichard Wright's novel, Native Son, presents Communism in many different lights. On the one hand, the pushy nature R of Jan and Mary, two white characters trying to share their beliefs about an equal society under Communism, by forcing Bigger, the black protagonist, to dine and drink with them, is ultimately what leads to Mary's death. -

How Bigger Was Born Anew

Fall 2020 29 ow Bier as Born new datation Reuration and Double Consciousness in Nambi E elle’s Native Son Isaiah Matthew Wooden This essay analyzes Nambi E. Kelley’s stage adaptation of Native Son to consider the ways tt Aicn Aeicn is itlie by n constitte to cts o etion t sharpens particular focus on how Kelley reinvigorates Wright’s novel’s searing social and cil cities by ctiely ein te oisin etpo o oble consciosness n iin ne o, enin, n se to te etpo, elleys Native Son extends the debates about “the problem of the color line” that Du Bois’s writing helped engender at te beinnin o te tentiet centy into te tentyst n, in so oin, opens citicl space to reckon with the persistent and pernicious problem of anti-Black racism. ewords adaptation, refguration, double consciousness, Native Son, Nambi E. Kelley This essay takes as a central point of departure the claim that African American drama is vitalized by and, indeed, constituted through acts of refguration. It is such acts that endow the remarkably capacious genre with any sense or semblance of coherence. Retion is notably a word with multiple signifcations. It calls to mind processes of representation and recalculation. It also points to matters of meaning-making and modifcation. The pref re does important work here, suggesting change, alteration, or even improvement. For the purposes of this essay, I use etion to refer to the strategies, practices, methods, and techniques that African American dramatists deploy to transform or give new meaning to certain ideas, concepts, artifacts, and histories, thereby opening up fresh interpretive and defnitional possibilities and, when appropriate, prompting much-needed reckonings. -

A Descriptive and Comparative Study of Conceptual Metaphors in Pop and Metal Lyrics

UNIVERSIDAD DE CHILE FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y HUMANIDADES DEPARTAMENTO DE LINGÜÍSTICA METAPHORS WE SING BY: A DESCRIPTIVE AND COMPARATIVE STUDY OF CONCEPTUAL METAPHORS IN POP AND METAL LYRICS. Informe final de Seminario de Grado para optar al Grado de Licenciado en Lengua y Literatura Inglesas Estudiantes: María Elena Álvarez I. Diego Ávila S. Carolina Blanco S. Nelly Gonzalez C. Katherine Keim R. Rodolfo Romero R. Rocío Saavedra L. Lorena Solar R. Manuel Villanovoa C. Profesor Guía: Carlos Zenteno B. Santiago-Chile 2009 2 Acknowledgements We would like to thank Professor Carlos Zenteno for his academic encouragement and for teaching us that [KNOWLEDGE IS A VALUABLE OBJECT]. Without his support and guidance this research would never have seen the light. Also, our appreciation to Natalia Saez, who, with no formal attachment to our research, took her own time to help us. Finally, we would like to thank Professor Guillermo Soto, whose suggestions were fundamental to the completion of this research. Degree Seminar Group 3 AGRADECIMIENTOS Gracias a mi mamá por todo su apoyo, por haberme entregado todo el amor que una hija puede recibir. Te amo infinitamente. A la Estelita, por sus sabias palabras en los momentos importantes, gracias simplemente por ser ella. A mis tías, tío y primos por su apoyo y cariño constantes. A mis amigas de la U, ya que sin ellas la universidad jamás hubiese sido lo mismo. Gracias a Christian, mi compañero incondicional de este viaje que hemos decidido emprender juntos; gracias por todo su apoyo y amor. A mi abuelo, que me ha acompañado en todos los momentos importantes de mi vida… sé que ahora estás conmigo. -

3 Feet High and Rising”--De La Soul (1989) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Vikki Tobak (Guest Post)*

“3 Feet High and Rising”--De La Soul (1989) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Vikki Tobak (guest post)* De La Soul For hip-hop, the late 1980’s was a tinderbox of possibility. The music had already raised its voice over tensions stemming from the “crack epidemic,” from Reagan-era politics, and an inner city community hit hard by failing policies of policing and an underfunded education system--a general energy rife with tension and desperation. From coast to coast, groundbreaking albums from Public Enemy’s “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” to N.W.A.’s “Straight Outta Compton” were expressing an unprecedented line of fire into American musical and political norms. The line was drawn and now the stage was set for an unparalleled time of creativity, righteousness and possibility in hip-hop. Enter De La Soul. De La Soul didn’t just open the door to the possibility of being different. They kicked it in. If the preceding generation took hip-hop from the park jams and revolutionary commentary to lay the foundation of a burgeoning hip-hop music industry, De La Soul was going to take that foundation and flip it. The kids on the outside who were a little different, dressed different and had a sense of humor and experimentation for days. In 1987, a trio from Long Island, NY--Kelvin “Posdnous” Mercer, Dave “Trugoy the Dove” Jolicoeur, and Vincent “Maseo, P.A. Pasemaster Mase and Plug Three” Mason—were classmates at Amityville Memorial High in the “black belt” enclave of Long Island were dusting off their parents’ record collections and digging into the possibilities of rhyming over breaks like the Honey Drippers’ “Impeach the President” all the while immersing themselves in the imperfections and dust-laden loops and interludes of early funk and soul albums. -

New Album from Rap MC Talib Kweli 11-22

New Album from Rap MC Talib Kweli 11-22 Written by Robert ID2069 Wednesday, 02 November 2005 08:22 - One of hip-hop’s highly charged and talented rap MC’s Talib Kweli will release his new CD "Right About Now...," thru KOCH Records and Blacksmith Music on November 22nd. The album features fellow hip-hop and rap artists Jean Grae, Mos Def, Papoose and others also features 12 all new tracks. The first singles "Who Got It," produced by Kareem Riggs, and "Fly That Knot" are reacting simultaneously at urban radio right now. Kweli states, "''Right About Now'' sums up this project. Usually when my music comes out, the people hear where I was a year ago. This project represents where I am right now." Rap artist Talib Kweli is currently co-headlining The Breed Love Odyssey Tour (sponsored by PlayStation and House of Blues) with Mos Def. The national tour continues through the end of the year and also features Jean Grae, Pharoahe Monch and Medina Green. Kweli is a member of legendary groups Black Star (with Mos Def) and Reflection Eternal (with super producer Hi-Tek), as well as a successful solo artist, and has established himself as one of the most skilled artists in hip-hop today. Kweli ranks among the most respected MCs in the game -- even garnering reverence from multi-platinum artist Jay-Z in his song "Moment of Clarity" on the platinum release "The Black Album." With lyrics that range from the classic battle rap to emotionally charged, socially conscious commentary, Kweli is an intelligent wordsmith who has the knack for bridging the gaps between hip-hop fans of all types. -

Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison: Conflicting Masculinities

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison: Conflicting Masculinities H. Alexander Nejako College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Nejako, H. Alexander, "Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison: Conflicting Masculinities" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625892. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nehz-v842 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RICHARD WRIGHT AND RALPH ELLISON: CONFLICTING MASCULINITIES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by H. Alexander Nejako 1994 ProQuest Number: 10629319 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10629319 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2011 No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson Jr. Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Horace E. Anderson, Jr., No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us, 20 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 115 (2011), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/818/. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No Bitin' Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson, Jr: I. History and Purpose of Copyright Act's Regulation of Copying ..................................................................................... 119 II. Impact of Technology ................................................................... 126 A. The Act of Copying and Attitudes Toward Copying ........... 126 B. Suggestions from the Literature for Bridging the Gap ......... 127 III. Potential Influence of Norms-Based Approaches to Regulation of Copying ................................................................. 129 IV. The Hip-Hop Imitation Paradigm ............................................... -

YASIIN BEY Formerly Known As “Mos Def”

The Apollo Theater and the Kennedy Center Present Final U.S. Performances for Hip-Hop Legend YASIIN BEY Formerly Known as “Mos Def” The Apollo Theater Tuesday, December 21st, 2016 The Kennedy Center New Year’s Eve Celebration at the Kennedy Center Concert Hall Saturday, December 31st, 2016 – Monday, January 2, 2017 (Harlem, NY) – The Apollo Theater and The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts announced today that they will present the final U.S. performances of one of hip hop’s most influential artists - Yasiin Bey (formerly known as Mos Def). These special engagements follow Bey’s announcement earlier this year of his retirement from the music business and will kick-off at the Apollo Theater on Tuesday, December 21st, culminating at The Kennedy Center from Saturday, December 31st through Sunday, January 2, 2017. Every show will offer a unique musical experience for audiences with Bey performing songs from a different album each night including The New Danger, True Magic, The Ecstatic, and Black on Both Sides, alongside new material. He will also be joined by surprise special guests for each performance. Additionally, The Kennedy Center shows will serve as a New Years Eve celebration and will feature a post-show party in the Grand Foyer. Yasin Bey has appeared at both the Apollo Theater and Kennedy Center multiple times throughout his career. “We are so excited to collaborate with the Kennedy Center on what will be a milestone moment in not only hip-hop history but also in popular culture. The Apollo is the epicenter of African American culture and has always been a nurturer and supporter of innovation and artistic brilliance, so it is only fitting that Yasiin Bey have his final U.S. -

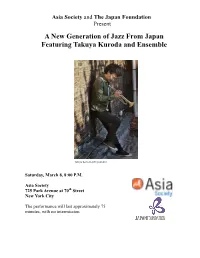

A New Generation of Jazz from Japan Featuring Takuya Kuroda and Ensemble

Asia Society and The Japan Foundation Present A New Generation of Jazz From Japan Featuring Takuya Kuroda and Ensemble Takuya Kuroda (Hiroyuki Seo) Saturday, March 8, 8:00 P.M. Asia Society 725 Park Avenue at 70th Street New York City The performance will last approximately 75 minutes, with no intermission. Asia Society and The Japan Foundation Present A New Generation of Jazz From Japan Featuring Takuya Kuroda and Ensemble THE ENSEMBLE: Takuya Kuroda, trumpet Rashaan Carter, bass Adam Jackson, drums Corey King, trombone Keita Ogawa, percussion Takeshi Ohbayashi, piano/keyboards ABOUT THE ARTISTS TAKUYA KURODA (TRUMPET) Japanese trumpeter Takuya Kuroda is a veteran and mainstay of the New York Jazz scene. A 2006 graduate of The New School’s Jazz and Contemporary Music Program, Takuya has performed alongside some of the best musicians (Junior Mance, Jose James, Greg Tardy, Andy Ezrin, Jiro Yoshida, Akoya Afrobeat, Valery Ponomarev Big Band) at some of the city’s most renowned live music venues including Radio City Music Hall, The Blue Note, The Village Underground, Sweet Rhythm, 55 Bar, and SOBs. RASHAAN CARTER (BASS) Rashaan Carter is entrenched in the New York jazz scene and has worked with Benny Golson, Curtis Fuller and Louis Hayes, Wallace Roney, Marc Cary, Cindy Blackman, Doug and Jean Carn, Antoine Roney, Sonny Simmons, and many more. ADAM JACKSON (DRUMS) Adam Jackson has had the pleasure of working with platinum recording group Destiny’s Child, Ciara, Grammy-nominated Emily King, Frank McComb and on the Tony Award winning musical Memphis. COREY KING (TROMBONE) Since his arrival in New York, Corey King has performed and/or recorded with notable artists such as Dave Binney, Dr.