How William F. Cody Helped Save the Buffalo Without Really Trying

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reimagining Dodge Appendices A

APPENDIX A DODGE CITY HISTORICAL ESSAY William M. Hunter, M.A. Heberling Associates, Inc. A-1 Dodge City Although seemingly remote, Dodge City has always linked to the broader world in important ways. Dodge City, working through the urban centers of the Middle West, was the meeting place of country and city where cattlemen from the prairie states accessed eastern markets (Cronon 1991:211-212). Indeed, the ecological transformation of mixed prairie into the current agriculture is but one manifestation of the interpenetration of city and country that continues to characterize the production of landscape (Cronon 1991: 212). The settlement of the area around Dodge by migrants from the Old Northwest introduced agents of landscape change into a new environment, one dependent on weather and climate and subject to drought (Cronon 1991:214). Only through extensive irrigation and the development of special techniques could farmers consistently produce staple crops, forcing many to adapt to the conditions and turn from the cultivation of wheat to the raising of livestock. However, if livestock was to become the foundation of a new western agriculture, farmers and ranchers had to transform the landscape by confining or eliminating its original human and animal inhabitants, particularly the vast millions of American bison (Cronon 1991:214). Prior to advent of the railroad, the herd of bison was a defining feature of the grasslands. With the introduction of the world economy into the region, market and sport hunters prized the bison, like the earlier furbearing animals of the east and upper Midwest, as commodities (Cronon 1991:216). The perfection of tanning bison hide by 1870 doomed the herds. -

The Formation of Temporary Communities in Anime Fandom: a Story of Bottom-Up Globalization ______

THE FORMATION OF TEMPORARY COMMUNITIES IN ANIME FANDOM: A STORY OF BOTTOM-UP GLOBALIZATION ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Geography ____________________________________ By Cynthia R. Davis Thesis Committee Approval: Mark Drayse, Department of Geography & the Environment, Chair Jonathan Taylor, Department of Geography & the Environment Zia Salim, Department of Geography & the Environment Summer, 2017 ABSTRACT Japanese animation, commonly referred to as anime, has earned a strong foothold in the American entertainment industry over the last few decades. Anime is known by many to be a more mature option for animation fans since Western animation has typically been sanitized to be “kid-friendly.” This thesis explores how this came to be, by exploring the following questions: (1) What were the differences in the development and perception of the animation industries in Japan and the United States? (2) Why/how did people in the United States take such interest in anime? (3) What is the role of anime conventions within the anime fandom community, both historically and in the present? These questions were answered with a mix of historical research, mapping, and interviews that were conducted in 2015 at Anime Expo, North America’s largest anime convention. This thesis concludes that anime would not have succeeded as it has in the United States without the heavy involvement of domestic animation fans. Fans created networks, clubs, and conventions that allowed for the exchange of information on anime, before Japanese companies started to officially release anime titles for distribution in the United States. -

FILM & TV GENRES: the Western

FILM & TV GENRES: The Western [J-Term, Taos, 2016] FILM 3300-0012 Dr. RICK WORLAND SMU Fort Burgwin Campus, Taos, NM. Daily, Jan 4-13. 9:00am-Noon; and 1:00-4:00pm. Hours: No regular office hours for J-term; email or see me after class. Phone: 214/768-3708 (Main campus office) email: [email protected] Required Text: Mary Lea Bandy & Kevin Stoehr, Ride, Boldly Ride: The Evolution of the American Western. (UC Press, 2012). Course Description: The genre film is inextricably linked with the Hollywood style of production. Yet our assumption will be that popular movie genres are not simply entertainment; they also present, challenge, and negotiate particular cultural values, assumptions, and conflicts. The Western is probably the most studied genre since it is closely tied in complex ways to American history itself. Until the mid 1970s, the Western was also the most perennially popular American movie genre; at this point it virtually disappeared. Why? The objectives of the class are: i) to describe some of the major conventions and concerns of the Western genre and its history; ii) introduce some concepts about the function of popular genres generally; iii) provide tools of film criticism and analysis applicable to a variety of films and genres. iv) understand how and why the Western evolved in relation to particular industry and historical forces over the years. Overall, we will study the movies with reference to American culture. Instructor Bio: Dr. Rick Worland received his Ph.D. in Motion Picture/Television Critical Studies from UCLA. He is a Professor in the Division of Film & Media Arts at SMU where his teaching includes Film History, Documentary, popular genres including the Western and the horror film, television history, and the films of Alfred Hitchcock. -

Community Newsletter Week of September 30 - October 4, 2019 a Publication of the City of Dodge City Public Information Office

Community Newsletter Week of September 30 - October 4, 2019 A publication of the City of Dodge City Public Information Office 1. A City Commission work session is scheduled for 6 pm on Monday, October 7th, before the regular meeting. The topics of discussion will include the City Manager selection process and a presentation of concepts for the Downtown Streetscape project. The streetscape project will be funded through STAR Bonds proceeds, and features improvements focused on Front Street, including new street lights, landscaping, pedestrian walkways, and other amenities. 2. Members of the Dodge City-Ford County Complete Count Committee attended the Grand Opening of the 2020 Census Headquarters Office in Wichita, Kansas. In addition, the Complete Count Committee launched its Facebook Page to educate and communicate with residents about the 2020 Census. You can search and like the Facebook page “Dodge City-Ford County Census 2020”. 3. Ernestor De La Rosa, Assistant City Manager/ Legislative Affairs, attended the first meeting of KDOT’s FORWARD/Long Range Transportation Plan Advisory Group. The meeting focused on ideas, strategies, and structure for the next state transportation plan. Moreover, KDOT will hold the next Local Consult Meeting in Southwest Kansas on November 19, 2019 in Liberal, Kansas (Seward County Community College, Student Wellness Building, 1801 North Kansas Ave. Liberal, KS 67901). This round of consult meetings is essential to attend as KDOT will look for a prioritization of projects for District 6 to include in the next plan. Below is a map with a complete list of the consult meetings around the state. 4. Ernestor De La Rosa, Assistant City Manager/Legislative Affairs, attended the Cities for Action Convening in Seattle, Washington, last week. -

NORMAN K Denzin Sacagawea's Nickname1, Or the Sacagawea

NORMAN K DENZIN Sacagawea’s Nickname1, or The Sacagawea Problem The tropical emotion that has created a legendary Sacajawea awaits study...Few others have had so much sentimental fantasy expended on them. A good many men who have written about her...have obviously fallen in love with her. Almost every woman who has written about her has become Sacajawea in her inner reverie (DeVoto, 195, p. 618; see also Waldo, 1978, p. xii). Anyway, what it all comes down to is this: the story of Sacagawea...can be told a lot of different ways (Allen, 1984, p. 4). Many millions of Native American women have lived and died...and yet, until quite recently, only two – Pocahantas and Sacagawea – have left even faint tracings of their personalities on history (McMurtry, 001, p. 155). PROLOGUE 1 THE CAMERA EYE (1) 2: Introduction: Voice 1: Narrator-as-Dramatist This essay3 is a co-performance text, a four-act play – with act one and four presented here – that builds on and extends the performance texts presented in Denzin (004, 005).4 “Sacagawea’s Nickname, or the Sacagawea Problem” enacts a critical cultural politics concerning Native American women and their presence in the Lewis and Clark Journals. It is another telling of how critical race theory and critical pedagogy meet popular history. The revisionist history at hand is the history of Sacagawea and the representation of Native American women in two cultural and symbolic landscapes: the expedition journals, and Montana’s most famous novel, A B Guthrie, Jr.’s mid-century novel (1947), Big Sky (Blew, 1988, p. -

Nebraska's Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Nebraska’s Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World Full Citation: William E Deahl Jr, “Nebraska’s Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World,” Nebraska History 49 (1968): 282-297 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1968Entertainment.pdf Date: 11/23/2015 Article Summary: Buffalo Bill Cody and Dr. W F Carver were not the first to mount a Wild West show, but their opening performances in 1883 were the first truly successful entertainments of that type. Their varied acts attracted audiences familiar with Cody and his adventures. Cataloging Information: Names: William F Cody, W F Carver, James Butler Hickok, P T Barnum, Sidney Barnett, Ned Buntline (Edward Zane Carroll Judson), Joseph G McCoy, Nate Salsbury, Frank North, A H Bogardus Nebraska Place Names: Omaha Wild West Shows: Wild West, Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition -

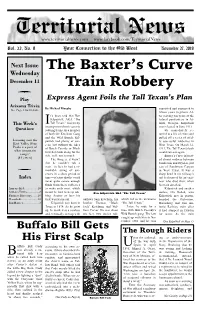

The Baxter's Curve Train Robbery

Territorial News www.territorialnews.com www.facebook.com/TerritorialNews Vol. 33, No. 9 Your Connection to the Old West November 27, 2019 Next Issue The Baxter’s Curve Wednesday December 11 Train Robbery Play Express Agent Foils the Tall Texan’s Plan Arizona Trivia By Michael Murphy convicted and sentenced to See Page 2 for Details fifteen years in prison. Af- t’s been said that Ben ter serving ten years at the Kilpatrick, AKA “The federal penitentiary in At- This Week’s I Tall Texan,” was pretty lanta, Georgia, Kilpatrick incompetent when it came to was released in June 1911. Question: robbing trains. As a member He immediately re- of both the Ketchum Gang turned to a life of crime and and the Wild Bunch, Kil- pulled off a series of mild- Looming over the patrick had plenty of suc- ly successful robberies in East Valley, Four cess, but without the likes West Texas. On March 12, Peaks is a part of of Butch Cassidy or Black 1912, The Tall Texan’s luck what mountain Jack Ketchum along for the would run out again. range? ride, well, not so much. Baxter’s Curve is locat- (8 Letters) The thing is, it wasn’t ed almost midway between that he couldn’t rob a Sanderson and Dryden, just train—in fact he had a re- east of Sanderson Canyon markable string of suc- in West Texas. It was a cesses in a short period of sharp bend in the railway’s Index time—it’s just that he could rail bed named for an engi- never quite secure enough neer who died there when funds from these robberies his train derailed. -

9. List of Film Genres and Sub-Genres PDF HANDOUT

9. List of film genres and sub-genres PDF HANDOUT The following list of film genres and sub-genres has been adapted from “Film Sub-Genres Types (and Hybrids)” written by Tim Dirks29. Genre Film sub-genres types and hybrids Action or adventure • Action or Adventure Comedy • Literature/Folklore Adventure • Action/Adventure Drama Heroes • Alien Invasion • Martial Arts Action (Kung-Fu) • Animal • Man- or Woman-In-Peril • Biker • Man vs. Nature • Blaxploitation • Mountain • Blockbusters • Period Action Films • Buddy • Political Conspiracies, Thrillers • Buddy Cops (or Odd Couple) • Poliziotteschi (Italian) • Caper • Prison • Chase Films or Thrillers • Psychological Thriller • Comic-Book Action • Quest • Confined Space Action • Rape and Revenge Films • Conspiracy Thriller (Paranoid • Road Thriller) • Romantic Adventures • Cop Action • Sci-Fi Action/Adventure • Costume Adventures • Samurai • Crime Films • Sea Adventures • Desert Epics • Searches/Expeditions for Lost • Disaster or Doomsday Continents • Epic Adventure Films • Serialized films • Erotic Thrillers • Space Adventures • Escape • Sports—Action • Espionage • Spy • Exploitation (ie Nunsploitation, • Straight Action/Conflict Naziploitation • Super-Heroes • Family-oriented Adventure • Surfing or Surf Films • Fantasy Adventure • Survival • Futuristic • Swashbuckler • Girls With Guns • Sword and Sorcery (or “Sword and • Guy Films Sandal”) • Heist—Caper Films • (Action) Suspense Thrillers • Heroic Bloodshed Films • Techno-Thrillers • Historical Spectacles • Treasure Hunts • Hong Kong • Undercover -

Hollywood Cinema Walter C

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Publications Department of Cinema and Photography 2006 Hollywood Cinema Walter C. Metz Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/cp_articles Recommended Citation Metz, Walter C. "Hollywood Cinema." The Cambridge Companion to Modern American Culture. Ed. Christopher Bigsby. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. (Jan 2006): 374-391. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Cinema and Photography at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Hollywood Cinema” By Walter Metz Published in: The Cambridge Companion to Modern American Culture. Ed. Christopher Bigsby. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006. 374-391. Hollywood, soon to become the United States’ national film industry, was founded in the early teens by a group of film companies which came to Los Angeles at first to escape the winter conditions of their New York- and Chicago-based production locations. However, the advantages of production in southern California—particularly the varied landscapes in the region crucial for exterior, on-location photography—soon made Hollywood the dominant film production center in the country.i Hollywood, of course, is not synonymous with filmmaking in the United States. Before the early 1910s, American filmmaking was mostly New York-based, and specialized in the production of short films (circa 1909, a one-reel short, or approximately 10 minutes). At the time, French film companies dominated global film distribution, and it was more likely that one would see a French film in the United States than an American-produced one. -

Calamity Jane

Calamity Jane Calamity Jane was born on May 1, 1852 in Princeton, Missouri. Her real name was Martha Jane Cannary. By the time she was 12 years old, both of her parents had died. It was then her job to raise her 5 younger brothers and sisters. She moved the family from Missouri to Wyoming and did whatever she could to take care of her brothers and sisters. In 1876, Calamity Jane settled in Deadwood, South Dakota, the site of a new gold rush. It has been told that during this time she met Wild Bill Hickok, who was known for his shooting skills. Jane would later say that she married him in 1873. Many people think this was not true because if you look at the years, she said she married him 3 years before she really met him. When she was in Deadwood, Jane carried goods and machinery to camps outside of the town and worked other jobs too. She was known for being loud and annoying. She also did not act very lady like. However, she was known to be very generous and giving. Jane worked as a cook, a nurse, a miner and an ox-team driver, and became an excellent horseback rider who was great with a gun. She was a good shot and a fearless rider for a girl her age. By 1893, Calamity Jane was appearing in Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show as a trick shooter and horse rider. She died on August 1, 1903, in Terry, South Dakota, at the age of 51. -

The Western by Eric Patterson the Cowboy Member of the Disco Group the Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, Glbtq, Inc

The Western by Eric Patterson The cowboy member of the Disco group The Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Village People wears a Entry Copyright © 2008 glbtq, Inc. costume derived from Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com those found in the Hollywood Western to create an instantly The Western is a distinctive American narrative genre that has developed over more recognizable than two centuries and now is recognized and consumed worldwide. Its most familiar hypermasculine persona. expressions are in literature, popular fiction, film, and television, but it also is This image created by important in painting, photography, music, sport, and advertising. Flickr contributor Jackie from Monouth County, New Jersey appears Heroic Western narratives have served to justify transformation and often destruction under the Creative of indigenous peoples and ecosystems, to rationalize the supposedly superior Commons Attribution 2.0 economic and social order organized by European Americans, and particularly to License. depict and enforce the dominant culture's ideals of competitive masculine individualism. The celebration of male power, beauty, and homosocial relationships in Westerns is compelling to many readers and viewers. Although the form of masculinity idealized in the Western is in opposition to the majority's stereotypical constructions of male homosexuality, both man-loving men and those who claim to reject same-sex attraction have found a great deal of interest in the narrative. Development and Form of the Western The national fantasy of the Western has its roots in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in the wars between Native Americans and European colonists. It developed during the rapid westward movement of settlers and the continuing conflict with native peoples after the American Revolution. -

FLM201 Film Genre: Understanding Types of Film (Study Guide)

Course Development Team Head of Programme : Khoo Sim Eng Course Developer(s) : Khoo Sim Eng Technical Writer : Maybel Heng, ETP © 2021 Singapore University of Social Sciences. All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Educational Technology & Production, Singapore University of Social Sciences. ISBN 978-981-47-6093-5 Educational Technology & Production Singapore University of Social Sciences 463 Clementi Road Singapore 599494 How to cite this Study Guide (MLA): Khoo, Sim Eng. FLM201 Film Genre: Understanding Types of Film (Study Guide). Singapore University of Social Sciences, 2021. Release V1.8 Build S1.0.5, T1.5.21 Table of Contents Table of Contents Course Guide 1. Welcome.................................................................................................................. CG-2 2. Course Description and Aims............................................................................ CG-3 3. Learning Outcomes.............................................................................................. CG-6 4. Learning Material................................................................................................. CG-7 5. Assessment Overview.......................................................................................... CG-8 6. Course Schedule.................................................................................................. CG-10 7. Learning Mode...................................................................................................