Taxonomic Studies Change Conservation Priorities in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops Fuscatus)

Adaptations of An Avian Supertramp: Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus) Chapter 6: Survival and Dispersal The pearly-eyed thrasher has a wide geographical distribution, obtains regional and local abundance, and undergoes morphological plasticity on islands, especially at different elevations. It readily adapts to diverse habitats in noncompetitive situations. Its status as an avian supertramp becomes even more evident when one considers its proficiency in dispersing to and colonizing small, often sparsely The pearly-eye is a inhabited islands and disturbed habitats. long-lived species, Although rare in nature, an additional attribute of a supertramp would be a even for a tropical protracted lifetime once colonists become established. The pearly-eye possesses passerine. such an attribute. It is a long-lived species, even for a tropical passerine. This chapter treats adult thrasher survival, longevity, short- and long-range natal dispersal of the young, including the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of natal dispersers, and a comparison of the field techniques used in monitoring the spatiotemporal aspects of dispersal, e.g., observations, biotelemetry, and banding. Rounding out the chapter are some of the inherent and ecological factors influencing immature thrashers’ survival and dispersal, e.g., preferred habitat, diet, season, ectoparasites, and the effects of two major hurricanes, which resulted in food shortages following both disturbances. Annual Survival Rates (Rain-Forest Population) In the early 1990s, the tenet that tropical birds survive much longer than their north temperate counterparts, many of which are migratory, came into question (Karr et al. 1990). Whether or not the dogma can survive, however, awaits further empirical evidence from additional studies. -

Bahamas: Endemics & Kirtland's Warbler 2019 BIRDS

Field Guides Tour Report Bahamas: Endemics & Kirtland's Warbler 2019 Mar 23, 2019 to Mar 27, 2019 Jesse Fagan For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Here we are in the Nassau airport at the end of our fun trip through the Bahamas. Thanks again to the group for a great time. This was another successful running of our short and fun itinerary to the Bahamas. We had awesome weather this year, and the birds didn't disappoint. We got to see all the possible endemics (including the local Bahama Oriole), several regional endemics (amazing looks at Great Lizard-Cuckoo and very cooperative West Indian Woodpecker), and, of course, wintering Kirtland's Warbler. Thanks to my fun group, and I look forward to seeing you again on another adventure. Jesse aka Motmot (from Dahlonega, Georgia) KEYS FOR THIS LIST One of the following keys may be shown in brackets for individual species as appropriate: * = heard only, I = introduced, E = endemic, N = nesting, a = austral migrant, b = boreal migrant BIRDS Podicipedidae (Grebes) LEAST GREBE (Tachybaptus dominicus) – A group of three birds seen on Eleuthera Island. PIEDBILLED GREBE (Podilymbus podiceps) – One distant bird seen on a large freshwater lake on Eleuthera Island. Columbidae (Pigeons and Doves) ROCK PIGEON (Columba livia) – In Marsh Harbour, Abaco Island. WHITECROWNED PIGEON (Patagioenas leucocephala) – Seen on all the islands. EURASIAN COLLAREDDOVE (Streptopelia decaocto) – This is where the North American invasion began. A burgled pet shop in 1974 and subsequent invasion of SE Florida was how it all started. -

Cuba Caribbean Endemic Birding VIII 3Rd to 12Th March 2017 (10 Days) Trip Report

Cuba Caribbean Endemic Birding VIII 3rd to 12th March 2017 (10 days) Trip Report Bee Hummingbird by Forrest Rowland Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader, Forrest Rowland Tour Participants: Alan Baratz, Ron and Cheryl Farmer, Cassia Gallagher, George Kenyon, Steve Nanz, Clive Prior, Heidi Steiner, Lucy Waskell, and Janet Zinn Trip Report – RBL Cuba - Caribbean Endemic Birding VIII 2017 2 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Tour Top Ten List: 1. Bee Hummingbird 6. Blue-headed Quail-Dove 2. Cuban Tody 7. Great Lizard Cuckoo 3. Cuban Trogon 8. Cuban Nightjar 4. Zapata Wren 9. Western Spindalis 5. Cuban Green Woodpecker 10. Gundlach’s Hawk ___________________________________________________________________________________ Tour Summary As any tour to Cuba does, we started by meeting up in fascinating Havana, where the drive from the airport to the luxurious (relatively, for Cuba) 5th Avenue Four Points Sheraton Hotel offers up more interesting sights than about any other airport drive I can think of. Passing oxcarts, Tractors hauling cane, and numerous old cars in various states of maintenance and care, participants made their way to one of the two Hotels in Cuba recently affiliated with larger world chain operations. While this might seem to be a bit of an odd juxtaposition to the indigenous parochial surroundings, the locals seem very excited to have the recent influx of foreign interest and monies to update and improve the local infrastructure, including this fine hotel. With the Russian embassy building dominating the skyline (a bizarre, monolithic, imposing structure indeed!) from our balconies, and the Caribbean on the horizon, we enjoyed the best Western Spindalis by Dušan Brinkhuizen accommodations in the city. -

Observations of New Bird Species for San Salvador Island, the Bahamas Michael E

Caribbean Naturalist No. 26 2015 Observations of New Bird Species for San Salvador Island, The Bahamas Michael E. Akresh and David I. King The Caribbean Naturalist . ♦ A peer-reviewed and edited interdisciplinary natural history science journal with a re- gional focus on the Caribbean ( ISSN 2326-7119 [online]). ♦ Featuring research articles, notes, and research summaries on terrestrial, fresh-water, and marine organisms, and their habitats. The journal's versatility also extends to pub- lishing symposium proceedings or other collections of related papers as special issues. ♦ Focusing on field ecology, biology, behavior, biogeography, taxonomy, evolution, anatomy, physiology, geology, and related fields. Manuscripts on genetics, molecular biology, anthropology, etc., are welcome, especially if they provide natural history in- sights that are of interest to field scientists. ♦ Offers authors the option of publishing large maps, data tables, audio and video clips, and even powerpoint presentations as online supplemental files. ♦ Proposals for Special Issues are welcome. ♦ Arrangements for indexing through a wide range of services, including Web of Knowledge (includes Web of Science, Current Contents Connect, Biological Ab- stracts, BIOSIS Citation Index, BIOSIS Previews, CAB Abstracts), PROQUEST, SCOPUS, BIOBASE, EMBiology, Current Awareness in Biological Sciences (CABS), EBSCOHost, VINITI (All-Russian Institute of Scientific and Technical Information), FFAB (Fish, Fisheries, and Aquatic Biodiversity Worldwide), WOW (Waters and Oceans Worldwide), and Zoological Record, are being pursued. ♦ The journal staff is pleased to discuss ideas for manuscripts and to assist during all stages of manuscript preparation. The journal has a mandatory page charge to help defray a portion of the costs of publishing the manuscript. Instructions for Authors are available online on the journal’s website (www.eaglehill.us/cana). -

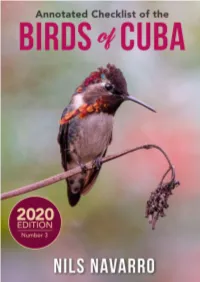

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 3 2020 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com 1 Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Bee Hummingbird/Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae), Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo courtesy Aslam I. Castellón Maure Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2020 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2020 ISBN: 978-09909419-6-5 Recommended citation Navarro, N. 2020. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos 3. 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. by his own illustrations, creates a personalized He is a freelance naturalist, author and an field guide style that is both practical and useful, internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and with icons as substitutes for texts. It also includes scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of other important features based on his personal Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as experience and understanding of the needs of field curator of the herpetological collection of the guide users. Nils continues to contribute his Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he artwork and copyrights to BirdsCaribbean, other described several new species of lizards and frogs NGOs, and national and international institutions in for Cuba. -

West Indian Mammals from the Albert Schwartz Collection: Biological and Historical Information

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum Museum, University of Nebraska State June 2003 West Indian Mammals from the Albert Schwartz Collection: Biological and Historical Information Robert M. Timm The University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas Hugh H. Genoways University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy Part of the Zoology Commons Timm, Robert M. and Genoways, Hugh H., "West Indian Mammals from the Albert Schwartz Collection: Biological and Historical Information" (2003). Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum. 107. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy/107 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Scientific Papers Natural History Museum The University of Kansas 16 June 2003 Number 29:147 West Indian Mammals from the Albert Schwartz Collection: Biological and Historical Information INatural History Museum & Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. The University of Kansas. Lawrence. Kansas 66045.7561. USA. *Universityof Nebraska State Museum & School of Natural Resource Sciences. W436 Nebraska Hall. University of Nebraska-Lincoln Lincoln. Nebraska -

Caribbean Conservation Trust ABA II CUBA Bird Survey April 5-17, 2011 ______Compiled, Written and Photos by Michael J

Caribbean Conservation Trust April 5-17, 2011 Cuba Bird Survey Caribbean Conservation Trust ABA II CUBA Bird Survey April 5-17, 2011 _______________________________________________________ Compiled, written and photos by Michael J. Good, MS Trip Summary: We tallied 166 species and counted 10,208 individual birds during our 10 day field trip, covering 2,630 KM around the country of Cuba. Subtracting the 2,406 Turkey Vultures (a higher concentration than in the US and certainly Maine!!) and 1601 Cattle Egret....that still leaves a respectable 6,201 individuals birds seen!! (For details go to Ebird.org) Participants: All participants were American citizens with varying degrees of birding experience. All very good in the field and excellent at locating birds in the scope and binoculars. We had one Photographer George Jett who helped to document many of the birds we saw. Everyone was engaging and involved and they were all gracious and understanding about the schedule of events for each day and the need to be prompt. Not one problem and we were never late for an early morning bird, like the Zapata Wren in La Turba or the Bee Hummingbird and Cuban Parrots in Bermejas. I enjoyed getting to know everyone and appreciated the opportunity to bird with them in Cuba. It was an honor. Kritchevsky, Evelyn Sholtes Bryn Mawr PA Soliday, Elke Matijevich Richardson TX Hardister, John Paul Jr. Concord NC Earle, Timothy Keese Winnetka IL Earle, Eliza Howe Winnetka IL Jett, George Waldorf MD Brewer, Gwen Waldorf MD Clegg, Eileen Columbia MD Derven, Peter Durango CO Derven, Ellen Durango CO Johnson, David Lloyd Cassopolis MI Sarah Boucas-Neto PA Weintraub, Rona Mill Valley CA Burkhart, Kathleen Miami FL The Staff This April’s staff included Dr. -

New Hope Audubon Society Newsletter Volume 33, Number 1: January-February 2007

New Hope Audubon Society Newsletter Volume 33, Number 1: January-February 2007 Conservation Corner – Jordan Lake by Joanna Hiller In my last article, I stated that I would like to take a closer look at places in North Carolina that tourists and local people love to visit. One of these is Jordan Lake. It is considered one of North Carolina’s treasured resources – as a recreational destination, as a natural habitat for significant flora and fauna, as an important water supply for thousands of North Carolinians, as well as a place for exploding development. The NC Division of Parks and Recreation operates eight recreation areas on the 46,768 acres lake – Crosswinds Campground, Ebenezer Church, Parkers Creek, Poplar Point Seaforth, Vista Point, Robeson Creek and New Hope Overlook. In 2004, one million people visited the lake for recreational purposes such as camping, fishing, swimming and hiking. Jordan Lake has achieved ecological importance through fish and wildlife conservation. Quite significantly, it has become one of the largest summertime homes of the bald eagle – thanks to vast, undisturbed regions of forest for nesting and plenty of fish to eat. The population of eagles in the Jordan Lake area has increased dramatically since the flooding of the reservoir in 1983. Although protection efforts have increased its numbers, the bald eagle still remains a rare species. The eagles congregate at the north end of the lake and can seen best from with the NC 751 Bridge crossing Northeast Creek or the Wildlife Resources Commission’s Wildlife Observation Deck. The observation deck is located five miles south of I-40 on 751, six-and-one-half miles north of US 64. -

Tour Report 29 February – 11 March 2016

Cuba Naturetrek Tour Report 29 February – 11 March 2016 West Indian Whistling Duck Cuban Emerald Report compiled by Byron Palacios Images courtesy of Michael New Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Cuba Tour Report Tour Participants: Byron Palacios (leader) together with 12 Naturetrek clients Local guides Santos (national guide), Cesar (La Güira), Orlando & Javier (Zapata), Camilo (La Belen) Yadier (Cayo Coco), Day 1 Monday 29th February UK – Havana – San Diego de los Baños The tour started with group members travelling to Havana from a number of different cities. We gathered together at Havana airport from where we started our journey of approximately two hours to the village of San Diego de los Baños, a buffer settlement of La Güira National Park. We arrived in time for a late dinner. Day 2 Tuesday 1st March La Güira National Park (La Cueva de los Portales & Hacienda Cortina) It was a beautiful sunrise at San Diego de los Baños on our first full day in Cuba. The loud metallic call of Greater Antillean Grackle and the melodic song of Northern Mockingbird got some of us out of our beds and to the hotel gardens to appreciate some of the island’s birdlife and our first Cuban endemics such as Cuba Blackbird and Cuban Emerald. The balcony by the restaurant was the perfect viewpoint to check the tree tops which produced views of some great birds including Tawny-shouldered Blackbird, Turkey Vulture, Mourning Dove, White-crowned Pigeon, Western Cattle Egret, West Indian Woodpecker, Cuban Green Woodpecker, Red-legged Honeycreeper and Western Osprey. -

Biology and Conservation of the Endangered Bahama Swallow (Tachycineta Cyaneoviridis)

Biology and conservation of the endangered Bahama Swallow (Tachycineta cyaneoviridis) Maya Wilson Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Biological Sciences Jeffrey R. Walters Daniel H. Catlin Sarah M. Karpanty Joel W. McGlothlin Meryl C. Mims November 22, 2019 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: endangered species, population distribution, population differentiation, cavity-nesting, nest-web, The Bahamas Copyright, Maya Wilson, 2019 Biology and conservation of the endangered Bahama Swallow (Tachycineta cyaneoviridis) Maya Wilson Abstract In order to prevent species extinctions, conservation strategies need to incorporate the identification and mitigation of the root causes of population decline with an assessment of vulnerability to genetic and stochastic factors affecting small populations. Species or populations with small ranges, such as those on islands, are particularly vulnerable to extinction, and deficient knowledge of these species often impedes conservation efforts. The Bahama Swallow (Tachycineta cyaneoviridis) is an endangered secondary cavity-nester that only breeds on three islands in the northern Bahamas: Abaco, Grand Bahama, and Andros. I investigated questions related to population size and distribution, genetic diversity and population structure, breeding biology, and ecological interactions of the swallow, with the goal of informing the conservation and management of the species. Using several population survey methods on Abaco, I found that swallow site occupancy and density is higher in southern Abaco, especially near roads and pine snags. Future research should prioritize identifying the causes of variable and low population densities in parts of the swallow’s range. I used microsatellite markers and morphometrics to assess differences between populations on Abaco and Andros. -

Cfreptiles & Amphibians

WWW.IRCF.ORG TABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES &IRCF AMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL &15, AMPHIBIANS NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 189 27(2):161–168 • AUG 2020 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES Predation. Chasing Bullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer on sayi) in Direct-developingWisconsin: Frogs On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 (Eleutherodactylidae:. The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: Eleutherodactylus ) A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 RESEARCHin Cuba: ARTICLES New Cases and a Review . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 Tomás. TheM. Knight Rodríguez-Cabrera Anole (Anolis equestris)1 in, L.Florida Yusnaviel García-Padrón2, Ernesto Morell Savall3, and Javier Torres4 .............................................Brian J. Camposano, Kenneth L. Krysko, Kevin M. Enge, Ellen M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 1Sociedad Cubana de Zoología, La Habana, Cuba ([email protected]) CONSERVATION2Museo de Historia Natural ALERT “Tranquilino Sandalio de Noda,” Martí 202, Pinar del Río, Cuba ([email protected]) 3Edificio. World’s 4, Apto Mammals 7, e/Oquendo in Crisis .............................................................................................................................. -

VIÑALES After an Mid Morning Arrival to Havana Airport, We Had Lunch in Old Havana. on Our Way to Viñales We

DAY 1 ARRIVAL - VIÑALES After an mid morning arrival to Havana airport, we had lunch in Old Havana. On our way to Viñales we stop by Las Terrazas looking for a Stygian Owl report seen it very well. After having a good introduction to some of the Caribbean specialties including Olive-capped Warbler, Black-whiskered Vireo and Red-legged Thrush present in a tree patch by a zip line tower, we had a show by Cuban and Yellow-faced Grassquits in a nearby farm. A good surprise on our way out was a Swallow-tailed Kite, not a bird to be expected. After that our next destination was our casas particulares and dinner at Viñales. Cuban Grassquit and Stygian Owl DAY 2 VIÑALES NATIONAL PARK (MARAVILLAS DE VIÑALES TRAIL), HISTORIC WALL, BENITO'S FARM, LOS JAZMINES, CUEVA DEL INDIO & EL PALENQUE Our first full day. The main targets here are easy to guess: whatever was on the way around Viñales! That was exactly what we did. The birds didn't disappointed us! Cuban Tody, Yellow-headed Warbler, Cuban Bullfinch, Cuban Trogon, Cuban Pewee among others. We move to our next spot, near the Historic Wall where we get the main target of the area: the Cuban Solitaire. We had awesome views along with some Cuban Vireo, more Cuban Tody views, one you never get tired to admire! Our next stop was Benito's Farm, a family owned tobacco farm where the participants had a chance to see the process to make cigars. Obviously, some got cigars as a gift or for their personal use right at the farm with some coffee and coffee with rum called "carajillo" Los Jazmines is where we had not just a wonderful Cuban lunch, but also a beautiful view of the Viñales region, and a few of our group danced to the salsa music being played by a local orchestra.