Re-Framing Memory. Between Individual and Collective Forms of Constructing the Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scraps of Folklore Collected by John Philipps Emslie

Folklore ISSN: 0015-587X (Print) 1469-8315 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfol20 Scraps of Folklore Collected by John Philipps Emslie C. S. Burne To cite this article: C. S. Burne (1915) Scraps of Folklore Collected by John Philipps Emslie, Folklore, 26:2, 153-170, DOI: 10.1080/0015587X.1915.9718868 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0015587X.1915.9718868 Published online: 01 Feb 2012. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 12 View related articles Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfol20 Download by: [University of Toronto Libraries] Date: 27 June 2016, At: 05:29 COLLECTANEA. SCRAPS OF FOLKLORE COLLICTED BY JOHN PHILIPPS EMSLIE. [THE late Mr. J. P. Emslie was a Londoner by birth, and an engraver by profession. He was accustomed throughout his life— ^839-1913—to make sketching excursions on foot in different parts of England, and to enquire into the local folklore by the way. What he heard he recorded in two small lamo notebooks, one dealing with London and its environs, the other with the country at large, which have now been presented by his executors to the Folklore Society. They will be placed in the Society's library, and the similar books containing topographical drawings, which accompanied them, in the London County Council's Museum. The following Notes represent the contents of the general commonplace book, arranged under counties by Miss Frances Henley of Charlton Kings. -

East Sussex Record Office Report of the County Archivist April 2008 to March 2009 Introduction

eastsussex.gov.uk East Sussex Record Office Report of the County Archivist April 2008 to March 2009 Introduction The year was again dominated by efforts towards achieving The Keep, the new Historical Resource Centre, but the core work of the Record Office continued more busily than ever and there was much of which to be proud. In July 2008 we took in our ten-thousandth accession, something of a milestone in the office’s own history of almost 60 years. An application to the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) for £4.9million towards the costs of The Keep was submitted by the Record Office on behalf of the capital partners, East Sussex County Council, Brighton & Hove City Council and the University of Sussex, in September. This represented around 20% of the anticipated costs of the building, since the partners remain committed to find the remainder. In December we learned our fate: that we had been unsuccessful. Feedback from the HLF indicated that ours had been an exemplary application, and one which they would have liked to have supported but, in a year when the effect of diverting HLF money to the Olympics was being felt, it was thought necessary to give precedence to some very high-profile projects. We were, of course, disappointed, but determined not to be deterred, and the partners agreed to pursue ways forward within the existing funding. Because it would further hold up the project, adding to inflation costs, but give no guarantee of success, we decided not to re-apply to the HLF, and by the end of the financial year were beginning to look at options for a less expensive building. -

Lewes Bonfire Celebrations Supplementary Report Agenda

Public Document Pack 25 June 2018 Dear Councillor Scrutiny Committee 28 June 2018 I am now able to enclose, for consideration, the following report at the above meeting that was unavailable when the agenda was printed. Item Item No 6 Lewes Bonfire Celebrations (Pages 1 - 38) Yours sincerely Robert Cottrill Chief Executive This page is intentionally left blank Agenda Item 6 Report to: Scrutiny Committee Date: 28 June 2018 Title: Lewes Bonfire Celebrations Report of: Director of Service Delivery Ward(s): Lewes, Falmer, Glynde, Southease and Cooksbridge Purpose of report: For Scrutiny Committee to consider the consultation event with Members held by the Chair of the Tactical Co-ordination Group for station closures on bonfire night on public safety grounds. Officer (1) To consider the consultation event which took place on 8 recommendation(s): June, which was presented by the Chair of the Tactical Co-ordination Group and attended by Lewes district, Lewes town and East Sussex county council members and representatives of blue light and related services (2) To note and consider officer advice which is as follows: That in recognition that the paramount concern at Bonfire is one of public safety, any decision around the operation of the train service is one which should be taken by strategic and tactical commanders, based on threat and risk, whilst taking into account and mitigating insofar as may be possible, those concerns raised by councillors (3) To consider whether Scrutiny Committee should make any recommendation to Cabinet as to the response which Lewes District Council should make to the consultation Reasons for Public safety at this event is of considerable concern and of recommendations: paramount importance. -

FIRE Fascination Fi...Pdf

www.rumblebook.co.uk fire fascination, firework and festival mark fleming fire fascination, firework and festival copyright © 2013 Mark Fleming designed and published by Rumble United Kingdom www.rumblebook.co.uk [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-9550621-3-1 All rights reserved. This electronic book edition is released with the intention of it being freely distributed. No charge must be made. This only applies to the electronic book in whole form. Otherwise, no part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means - graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems - without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. Contents introduction 1 fire 5 Guy Fawkes 13 gunpowder 27 the makers 53 culture 87 acknowledgments 102 photo credits 103 links 105 fire fascination, firework and festival introduction So, like a forgotten fire, a childhood can always flare up again within us. Gaston Bachelard he excitement reached its peak before Any lingering romance came with the the countdown. There came a ripple blisters of tying endless tubes to wooden Tof noise from the crowd when the stakes, with fingers made purple by cold. firework lighters lit their portfires, before But, bit by bit, the waiting display grew, the taking their positions beside the fireworks. fireworks readied and covered against the The display stood poised and loaded, ready seasonal damp. Aerial shells nestled at the to make the night its own. Most in the crowd bottom of their launch tubes, fuses dangling looked to the sky in anticipation, their eyes over-the-top, fixed with paper tape to stop picking through clouds of breath and the the breeze flapping them about. -

LEWES BONFIRE PORTRAITS Fawkes Night with a Bonfire Celebration of Epic Proportions

Please do not add text to the spine of this book. The spine of this book is too small to safely accommodate text. If you place text on the spine, it could cause the book to be rejected. BACK COVER PORTRAITS LEWES BONFIRE FRONT COVER On the 5th Of nOvember my home town of Lewes commemorates Guy LEWES BONFIRE PORTRAITS Fawkes Night with a Bonfire celebration of epic proportions. Quiet streets turnThese wild instructions with flaming should torches not andappear exploding in your fireworks, exported PDF.and swell with Cover Type: Softcover (Perfect Bound) visitors eager to witness costumed locals processing through the streets. Book Size: Small Square 7x7 Please note, all critical text and art should appear within this gray area. Page Count: 88 BonfireAny content is a outsidefiercely thisindependent area may beevent. unevenly Funded trimmed and organised or hidden bywhen Lewes’ Paper Type: Premium Lustre (100# Text) seventhe book Bonfire is bound. societies, If you it’s would for thelike participantsyour artwork tomore extend than tothe the onlookers. very edge of your finished book, then pull your artwork edge to the red bleed Theline. elaborate costumes and colour-coded striped jumpers are a sign of belonging, a clue to which society you’re with. Members march in remembrance,Please be sure asto completea rite of passage,your Pages to designcelebrate prior the to rebellious creating spirityour of Cover template. The Page Count must be exact when creating your thoseCover who template. fought for our freedoms, and for the joy of it. PhotographyBe sure to review is my wayyour of exported understanding PDF in the an significanceoutside application of Bonfire (like to thoseAdobe who Reader) march to through ensure Lewes’ it appears hilly streetscorrectly until and their without feet ache these and theirinstructions. -

Tales and Churches and Tales of Churches the First Leg of The

Tales and Churches and Tales of Churches The first leg of the legendary 18-miler ended with Shetland ponies in the village of Firle. The waist-high animals were unendingly friendly in their welcome, ambling over from their grazing spots to willingly be petted. Needless to say, they were an instant hit. “Can we ride them?” I had half-jokingly asked when first told that we would be encountering these cute-tastic creatures. My question had been met with chuckling doubt as to the animals’ ability to hold us, but there is an even more compelling reason not to saddle up one of these little beasts. Shetland folklore, naturally obligated to make mention of the distinctive animals, brings us the njuggle. A folkloric waterhorse inclined to potentially malevolent pranks, the njuggle is a nuisance primarily to millers in its harmlessly playful incarnation, hiding under the mill and interfering with its operation but easily banished with a lump of burning peat. Its more sinister side resembles its Celtic analog, the kelpie. In the form of a splendid Shetland pony, the njuggle wanders about until some unwary weary traveler, perhaps lured by the ill-intent of the creature or perhaps just by unlucky circumstance, mounts its back. With this, the njuggle gallops headlong into the nearest loch, often drowning the hapless traveler who ought to have known better than to accept a ride from a Shetland pony. There were no lochs nearby, only the river Ouse. Either way, it was a less fanciful instinct that kept me off the ponies’ backs; but their deep eyes and calm acquiescence to human overtures of friendship seemed to me a perfect lure. -

East Sussex Health and Wellbeing Board

EAST SUSSEX HEALTH AND WELLBEING BOARD TUESDAY, 8 DECEMBER 2020 2.30 PM CC2, COUNTY HALL, LEWES ++Please note that this meeting is taking place remotely++ MEMBERSHIP - Councillor Keith Glazier, East Sussex County Council (Chair) Councillor Carl Maynard, East Sussex County Council Councillor John Ungar, East Sussex County Council Councillor Trevor Webb, East Sussex County Council Councillor Philip Lunn, Wealden District Council Councillor Paul Barnett, Hastings Borough Council Louise Ansari, East Sussex Clinical Commissioning Group Jessica Britton, East Sussex Clinical Commissioning Group Dr David Warden, East Sussex Clinical Commissioning Group Mark Stainton, Director of Adult Social Care and Health Stuart Gallimore, Director of Children's Services, ESCC Darrell Gale, Director of Public Health John Routledge, Healthwatch East Sussex Sarah MacDonald, NHS England South (South East) Joanne Chadwick-Bell, East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust Siobhan Melia, Sussex Community NHS Trust Simone Button, Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (SPFT) INVITED OBSERVERS Councillor Rebecca Whippy, Eastbourne Borough Council WITH SPEAKING RIGHTS Councillor Zoe Nicholson, Lewes District Council Councillor John Barnes MBE, Rother District Council Becky Shaw, Chief Executive, ESCC Michelle Nice, Voluntary and Community Sector Representative Mark Matthews, East Sussex Fire and Rescue Service Katy Bourne, Sussex Police and Crime Commissioner A G E N D A 1 Minutes of meeting of Health and Wellbeing Board held on 17 September (Pages 3 - 10) 2 Apologies for absence 3 Disclosure by all members present of personal interests in matters on the agenda 4 Urgent items Notification of items which the Chair considers to be urgent and proposes to take at the end of the agenda. -

Christianity: a History

Christianity: A History A series of personal perspectives g Foreword 6 BC Quirinius becomes Aaqil Ahmed, Governor of Syria and conducts census Commissioning Editor Religion & Multicultural, Channel 4 c8–4 BC Birth of Jesus Christianity: A History is the biggest project I have commissioned during my time at Channel 4. It’s almost unheard of for a mainstream broadcaster to dedicate eight hours of c28 AD prime time television to Christianity in this way. I think it’s fair to say that it’s a big risk, but a John the Baptist begins his ministry; risk we really wanted to take. he baptises Jesus c29 and is later arrested Jesus begins ministry, Why? Because, of the sheer scale of the project and the complexity of the story at its very and beheaded preaching: ‘Repent, for heart. As with all religions, the history of Christianity is not a simple one. It contains dark the kingdom of heaven c32 moments, compromises and great achievements, and features life changing heroes and is near’ Execution of villains. We feel that now is the right time for Channel 4 to present these stories in a way that John the Baptist will inform our audience about how this faith has shaped our world, and more specifically, our c30–36 nation. Episode 1: Crucifixion of Jesus Two examples of Christianity’s impact on our modern world are the Reformation and the Jesus c37 Crusades. Without the Reformation we may not have become a Protestant nation with many Conversion of Paul of the characteristics, language and structures we take for granted today. -

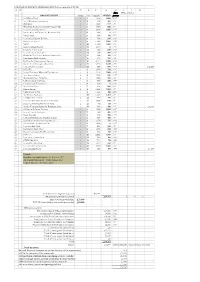

FINANCIAL GRANTS AWARDED 2018/19 Year Sorted by CYCLE a B C D E F G H I J K Stat

FINANCIAL GRANTS AWARDED 2018/19 Year sorted by CYCLE A B C D E F G H I J K Stat. Fwd provision line ORGANIZATION Cycle ref request AWARD power 1 LGB Brass Band 1 1 1,000 1,000 s145 2 Nevill Residents Association 1 2 200 200 s137 3 Riffrafters 1 3 1,800 972 s19 4 Woodkids: Lewes Community Nature Club 1 4 1,000 800 s19 5 Lewes Community Events 1 5 2,000 1,000 s145 6 North, West and Market St. Residents Assc. 1 6 500 0 s137 7 Visual Artist 1 7 300 150 GPC 8 Commercial Square Bonfire 1 8 500 500 s145 9 Plastic Free Lewes 1 9 1,969 1,000 s142 10 MTRA 1 10 1,990 1,000 s137 11 Secret Orchard Project 1 11 1,999 0 s137 12 Lewes Live Literature 1 12 600 600 s145 13 Lewes Concert Orchestra 1 13 500 500 s145 14 Windrush 70 Creative Writing Competition 1 14 300 300 s137 15 East Sussex Radio Society 1 15 970 900 s145 16 DeMontfort Improvement Group 1 16 2,143 1,500 s142 17 Stories Seen Through a Glass Plate 1 17 1,330 1,330 s144 18 Lewes Bonfire Council 1 18 500 500 s144 £12,252 19 RELATE 2 1 1,500 750 s137 20 Lewes Holocaust Memorial Day Group 2 2 1,778 1,000 s144 21 New Sussex Opera 2 3 1,000 500 s145 22 The Musicians of All Saints 2 4 1,000 550 s145 23 Lewes Concert Orchestra 2 5 500 500 s145 24 Crowborough Foundation 2 6 300 0 s142 25 The Bevern Trust 2 7 910 500 s19 26 Pippas Group 2 8 3,000 2,000 s19 27 Lewes Passion Play 2 9 1,000 400 GPC 28 The Dance Academy 2 10 1,163 1,163 s19 29 Landport Travel Club 2 11 390 390 s19 30 Lewes Community Allotment – Flourish 2 12 2,000 850 s19 31 Sussex Community Rail Partnership 2 13 80 80 s137 32 North, West and Market St. -

East Sussex Record Office Report of the County Archivist 2010-11

Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................1 Public Services.............................................................................................3 Public Service statistics................................................................................4 Outreach and Learning.................................................................................5 Document Services ......................................................................................7 Work in Brighton and Hove ........................................................................20 Conservation ..............................................................................................25 Records Management ................................................................................27 Staff and Volunteers...................................................................................28 Friends of the East Sussex Record Office..................................................29 Appendix 1 – Record Office Staff, 2010/11 ................................................32 Appendix 2 – East Sussex Accessions ......................................................33 Appendix 3 – Brighton and Hove Accessions.............................................42 Introduction We began the year in a new department (Governance and Community Services) and a new place in the structure as part of Libraries and Culture. This has helped to strengthen still further our joint working with libraries. -

Downland Thymes Spring

DOWNLAND THYMES SPRING DOWNLAND NEWS FOR THE SOUTH DOWNS VOLUNTEER THYMES RANGER SERVICE ISSUE 91 | SPRING 2021 DOWNLAND THYMES SPRING DOWNLAND THYMES SPRING CHAIR’S CORNER I struggled to know what to say to everyone this time around. Volunteering has been so quiet. What on earth is there to talk about? On 25 January the VRS committee held a Gently my wife reminds me. Scepticism. zoom meeting to discuss the finer details At least I’ve done the responsible thing for the AGM, due in March. A very and stayed indoors. Self-aggrandism. pleasant and productive meeting, but a committee meeting on Zoom is hardly Like I had a choice. I was immobile most newsworthy stuff. This year is the 40th of the time. Reflectivism. anniversary of the VRS, so it is important Can’t wait to get back at life though. to mark the occasion at the AGM. Futurism. But what to say now? I note down a few Editor’s Note Ah, but ‘gently’ the specialist said. bullet points. Respect. Specialism. If the last year has shown us I wrote: ‘Share a personal perspective’. anything, it’s that we can all get And we are still in the middle of this some strength and solace from our thing. Realism. I badly hurt my back a couple of months natural surroundings. As a member ago! The cause? Lockdown activity! Now get on and write something. of the Comms Team at South Downs Breaking up concrete, resulting in Journalism. National Park it’s been astonishing to a slipped disc. Those who know me see that even when access to nature Return to ‘normal’ is often a slow, will know that I am always over doing and inspiring views is restricted to challenging and emotional process. -

History Study 2021

History Study 2021 January 2021: HAZARDOUS INDUSTRIES First meeting of the New, hopefully better, Year. It was a grim subject, Hazardous Industries, and some of our presentations were pretty horrifying. I think by the end of the meeting we were all thankful that, in spite of Covid lockdown, we live in these times and not in the Industrial Revolution or Victorian times. A very informative and interesting meeting, however. We covered Coal Mining (a full length 20 minute video), leather tanning, hat-making (mercury to help soften beaver skin produced the mad-hatter disease), textiles, chain making and the radium dial workers of US/Canada. This latter industry was one I have never heard of before – in the 1920s it became a fashion to paint watch and clock dials with luminous radium paint. In spite of the fact that the men working in the labs to produce the paint wore lead aprons and took other precautions, the girls painting the dials were told it was completely safe (including licking the tiny paint brushes to “point” them). The resulting illnesses were similar to “phossy jaw” in match making. For a while it was believed that radium gave you energy so it was put into drinks, toothpastes etc. and, liking the luminescent look, women bought radium cosmetics too. It is thought around 50 dial painters died but many more were made seriously ill and after protracted court cases were compensated, Chain making is another lesser-known industry – if you want to learn more look up the white slaves of Cradley Heath. This was a major “cottage” industry for women living in the black country in the late 19th century.