What Is in a Gift?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance Art

(hard cover) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Master of Arts Fine Arts 2006 LASALLE-SIA COLLEGE OF THE ARTS (blank page) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts) LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts Faculty of Fine Arts Singapore May, 2006 ii Accepted by the Faculty of Fine Arts, LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts). Vincent Leow Studio Supervisor Adeline Kueh Thesis Supervisor I certify that the thesis being submitted for examination is my own account of my own research, which has been conducted ethically. The data and the results presented are the genuine data and results actually obtained by me during the conduct of the research. Where I have drawn on the work, ideas and results of others this has been appropriately acknowledged in the thesis. The greater portion of the work described in the thesis has been undertaken subsequently to my registration for the degree for which I am submitting this document. Lee Wen In submitting this thesis to LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations and policies of the college. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made available and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. This work is also subject to the college policy on intellectual property. -

Exhibition Guide

ArTScience MuSeuM™ PreSenTS ceLeBrATinG SinGAPOre’S cOnTeMPOrArY ArT Exhibition GuidE Detail, And We Were Like Those Who Dreamed, Donna Ong Open 10am to 7pm daily | www.MarinaBaySands.com/ArtScienceMuseum Facebook.com/ArtScienceMuseum | Twitter.com/ArtSciMuseum WELCOME TO PRUDENTIAL SINGAPORE EYE Angela Chong Angela chong is an installation artist who Prudential Singapore Eye presents a with great conceptual confidence. uses light, sound, narrative and interactive comprehensive survey of Singapore’s Works range across media including media to blur the line between fiction and contemporary art scene through the painting, installation and photography. reality. She has shown work in Amsterdam Light Festival in the netherlands; Vivid works of some of the country’s most The line-up includes a number of Festival in Sydney; 100 Points of Light Festival innovative artists. The exhibiting artists who are gaining an international in Melbourne; cP international Biennale in artists were chosen from over 110 following, to artists who are just Jakarta, indonesia, and iLight Marina Bay in submissions and represent a selection beginning to be known. Like all the other Singapore. of the best contemporary art in Prudential Eye exhibitions, Prudential 3D Tic-Tac-Toe is an interactive light sculpture Singapore. Prudential Singapore Eye is Singapore Eye aims to bring to light which allows multiple players of all ages to the first major exhibition in a year of a new and exciting contemporary art play Tic-Tac-Toe with one another. cultural celebrations of the nation’s 50th scene and foster greater appreciation of anniversary. Singapore’s visual art scene both locally and internationally. 3D Tic-Tac-Toe, 2014 The works of the exhibiting artists demonstrate versatility, with many of the artists working experimentally Jeremy Sharma Jeremy Sharma works primarily as a conceptual painter. -

Curriculum Vitae

HO TZU NYEN何子彥 CURRICULUM VITAE 1976 Born in Singapore 2007 Graduated from National University of Singapore, Master of Art (by Research), Southeast Asian Studies Programme 2001 Graduated from University of Melbourne, Victorian College of the Arts, School of Creative Arts (Dean's Awards), Bachelor of Creative Arts Currently lives and works in Singapore SELECTED VISUAL ARTS EXHIBITIONS 2010 Media Landscape -Zone East, The Korean Cultural Centre, London, United Kingdom Liverpool Biennial, Media Landscape -Zone East, Liverpool, United Kingdom Solo exhibition at the Contemporary Art Centre South Australia, Australia No Soul for Sale, Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom Video Art Biennial, Tel Aviv, Israel intercool 3.0, Hartware Medienkunstverein im Dortmunder U, Dortmund, Germany ShContemporary, Future Perfect, Shanghai, China 2009 The Zarathustra Project, 6th Asia-Art Pacific Triennial, Australia H the Happy Robot, 6th Asia-Art Pacific Triennial, Australia Yokomama Festival of Art and Media, Japan The Dojima River Biennale, Osaka, Japan The Making of the New Silk Roads, Bangkok University Gallery, Thailand The Singapore Art Show, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore Some Rooms, Osage Kwun Tong, Hong Kong, China 2008 Coffee, Cigarettes and Phad Thai- Contemporary Art from Southeast Asia, Eslite Gallery. Taiwan Art Multiple, Ke Center for the Contemporary Arts, Shanghai, China Loop in Motion, Video Festival, Seoul, South Korea MU Popshop, Stichting MU, Eindhoven, The Netherlands HO TZU NYEN何子彥 CURRICULUM VITAE Art & Entrepreneurship, Credit-Suisse -

Art of Tang Da Wu

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Body and communication : the ‘ordinary’ art of Tang Da Wu Wee, C. J. Wan‑Ling 2018 Wee, C. J. W.‑L. (2018). Body and communication : the ‘ordinary’ artof Tang Da Wu. Theatre Research International, 42(3), 286‑306. doi:10.1017/S0307883317000591 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/144518 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0307883317000591 © 2018 International Federation for Theatre Research. All rights reserved. This paper was published by Cambridge University Press in Theatre Research International and is made available with permission of International Federation for Theatre Research. Downloaded on 27 Sep 2021 10:02:22 SGT Accepted and finalized version of: Wee, C. J. W.-L. (2018). ‘Body and communication: The “Ordinary” Art of Tang Da Wu’. Theatre Research International, 42(3), 286-306. C. J. W.-L. Wee [email protected] Body and Communication: The ‘Ordinary’ Art of Tang Da Wu Abstract What might the contemporary performing body look like when it seeks to communicate and to cultivate the need to live well within the natural environment, whether the context of that living well is framed and set upon either by longstanding cultural traditions or by diverse modernizing forces over some time? The Singapore performance and visual artist Tang Da Wu has engaged with a present and a region fractured by the predations of unacceptable cultural norms – the consequences of colonial modernity or the modern nation-state taking on imperial pretensions – and the subsumption of Singapore society under capitalist modernization. Tang’s performing body both refuses the diminution of time to the present, as is the wont of the forces he engages with, and undertakes interventions by sometimes elusive and ironic means – unlike some overdetermined contemporary performance art – that reject the image of the modernist ‘artist as hero’. -

After Utopia Premises the Idea of Utopia on Four Prospects

1 May – 18 Oct 2015 Organised by Supported by In celebration of © 2015 Singapore Art Museum © 2015 Individual contributors All artworks are © the artists unless otherwise stated. Information correct at the time of the publication. Exhibition Curators: Tan Siuli Louis Ho Artwork captions by: Joyce Toh (JT) 1 May – 18 Oct 2015 Tan Siuli (TSL) Louis Ho (LH) All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for purposes of private study, research, criticism, or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior consent from the Publisher. Printer: AlsOdoMinie, Singapore Cover Image: H. Eichhorn, Tropic Woods (detail), issued by Meyers, lithographed by Bibliographisches Institut Leipzig, 1900, as featured in Donna Ong, The Forest Speaks Back (I), 2014. Photograph by John Yuen. Image courtesy of the Artist. Inside Cover Image: Maryanto, Pandora’s Box (detail), 2013, 2015. Image courtesy of the Artist. n naming his fictional island ‘Utopia’, writer Thomas More conjoined the Greek words for ‘good place’ and ‘no place’ – a reminder that the idealised society he conjured was fundamentally phantasmal. And yet, the search and yearning for utopia is a ceaseless humanist endeavour. Predicated on possibility and hope, utopian principles and models of worlds better than our own have been perpetually re-imagined, and through the centuries, continue to haunt our consciousness. Where have we located our utopias? How have we tried to bring into being the utopias we have aspired to? How do these manifestations serve as mirrors to both our innermost yearnings as well as to our contemporary realities – that gnawing sense that this world is not enough? Drawing largely from SAM’s permanent collection, as well as artists’ collections and new commissions, After Utopia premises the idea of Utopia on four prospects. -

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-Making

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 6 Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Antoinette, Michelle, author. Title: Contemporary Asian art and exhibitions : connectivities and world-making / Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner. ISBN: 9781925021998 (paperback) 9781925022001 (ebook) Subjects: Art, Asian. Art, Modern--21st century. Intercultural communication in art. Exhibitions. Other Authors/Contributors: Turner, Caroline, 1947- author. Dewey Number: 709.5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover illustration: N.S. Harsha, Ambitions and Dreams 2005; cloth pasted on rock, size of each shadow 6 m. Community project designed for TVS School, Tumkur, India. © N.S. Harsha; image courtesy of the artist; photograph: Sachidananda K.J. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction Part 1 — Critical Themes, Geopolitical Change and Global Contexts in Contemporary Asian Art . 1 Caroline Turner Introduction Part 2 — Asia Present and Resonant: Themes of Connectivity and World-making in Contemporary Asian Art . 23 Michelle Antoinette 1 . Polytropic Philippine: Intimating the World in Pieces . 47 Patrick D. Flores 2 . The Worlding of the Asian Modern . -

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-Making

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 6 Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Antoinette, Michelle, author. Title: Contemporary Asian art and exhibitions : connectivities and world-making / Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner. ISBN: 9781925021998 (paperback) 9781925022001 (ebook) Subjects: Art, Asian. Art, Modern--21st century. Intercultural communication in art. Exhibitions. Other Authors/Contributors: Turner, Caroline, 1947- author. Dewey Number: 709.5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover illustration: N.S. Harsha, Ambitions and Dreams 2005; cloth pasted on rock, size of each shadow 6 m. Community project designed for TVS School, Tumkur, India. © N.S. Harsha; image courtesy of the artist; photograph: Sachidananda K.J. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction Part 1 — Critical Themes, Geopolitical Change and Global Contexts in Contemporary Asian Art . 1 Caroline Turner Introduction Part 2 — Asia Present and Resonant: Themes of Connectivity and World-making in Contemporary Asian Art . 23 Michelle Antoinette 1 . Polytropic Philippine: Intimating the World in Pieces . 47 Patrick D. Flores 2 . The Worlding of the Asian Modern . -

MEDIA RELEASE the Collectors Show Returns with New, Rarely-Seen

MEDIA RELEASE For Immediate Release The Collectors Show returns with new, rarely-seen treasures from private collections 22 January 2013, Singapore – The Singapore Art Museum (SAM) & Credit Suisse are proud to present the third edition of The Collectors Show, one of the most anticipated exhibitions on Singapore’s arts calendar. Independently curated and organised by SAM, and sponsored by Credit Suisse as part of its Innovation in Art series, the exhibition draws from important private collections to present 23 contemporary masterpieces from the Asia-Pacific region. This exceptional exhibition series draws entirely from the private collections of individuals, art foundations, private museums and other organizations, offering museum-goers a unique glimpse into spectacular artworks normally held behind closed doors. The Collectors Show reflects the impact of museum-curated exhibitions in helping visitors find new ways to look at contemporary art. The theme of each exhibition connects the disparate pieces of art together in a thoughtful way, linking the art to our larger contemporary society and culture. Titled ‘Weight of History’, this year’s Collectors Show examines how artists engage with and evaluate local traditions and culture, displaying interconnected relationships between past and present in our increasingly globalised societies. Through the eyes of contemporary artists, Weight of History aims to raise questions about what defines history and how personal accounts of the past are just as valuable as official depictions of historical events, and why the past is still relevant to contemporary art making in Asia. Artists presented in the show hail from across the Asia-Pacific region, including China, Japan, Korea, India, Pakistan, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, Australia, as well as Tibet and Taiwan. -

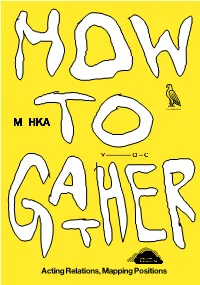

Acting Relations, Mapping Positions Part I: the Individual HOW to GATHER Acting Relations, Mapping Positions

Kunsthalle Wien Acting Relations, Mapping Positions Part I: The Individual HOW TO GATHER Acting Relations, Mapping Positions 3 21 Bart De Baere, Defne Ayas, Keren Cytter — Nicolaus Schafhausen — Note From Bed Background 23 9 Hanne Lippard — Marie Egger — Here’s it Editorial 25 Sergey Bratkov — Predictions on the Moon 33 Liam Gillick — Letters from Moscow 43 Li Mu — The Labourer 63 Ho Tzu-Nyen and Lee Weng-Choy — Curation is Also a Form of Transportation 77 Lee Weng-Choy — Three Degrees of Intimacy 81 Meggy Rustamova — Waiting for the Secret (Script) 85 Johanna van Overmeir — Janus 88 Janus Faced Freedom Marina Simakova Part II: In Relation Part III: Political Gestures HOW TO GATHER Acting Relations, Mapping Positions 89 119 176 225 Peter Wächtler — Mián Mián and Konstantin Zvezdochotov — Anna Jermolaewa and Leather Man / Woman of Nicolaus Schafhausen — About Ezgin Altinses Vanessa Joan Müller — the Bistro Talkshow Political Extras 180 104 131 Inventing Ritual 237 Jimmie Durham — Communicative Failures Leon Kahane — A Stone and Defeats 186 Figures of Authority Andrey Shental Gabriel Lester — 108 MurMure 243 Donna Kukama — 132 Nástio Mosquito — The Cemetery for Bad Honoré δ’O and 195 SOUTH Behaviours Fabrice Hyber — Honoré δ’O — Telepathic Protocol The Ten Commandments 246 114 Saâdane Afif — On Intimacy 137 215 Play Opposite Maria Kotlyachkova, Nadia Qiu Zhijie — Vaast Colson — Gorokhova Map of the Third World Ten Side Notes as Warm Up 250 Rana Hamadeh — 140 219 Performance Script Augustas Serapinas — Andrey Kuzkin — Conversation Behind -

Stirring a Fine Brew

GBA4 | GBAFOCUS Friday, June 5, 2020 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY Art the HKbox art galleries are open for Out of business again. Tai Kwun Contemporary is back with two new art exhibitions — including one on the timely theme of confinement. Chitralekha Basu reports. Ho Tzu Nyen’s Earth is a spectacular video installation, paying homage to a range of Jun Nguyen Hatsushiba’s video offers a surreal take classical European Renaissance paintings. Now on show at Tai Kwun Contemporary. on the plight of the Vietnamese boat people. ittingly, one of the two exhibitions as photo display boxes. of St James’ e ective and awkward. launched to mark the reopening of The steel cages contain a set of Settlement, a There are more pieces in the show Tai Kwun Contemporary on May 25 four photographs taken by Thai art- charity that helps underscoring the complicated, potential- explores the idea of being boxed in. ist Pratchaya Phinthong. At first rehabilitate people ly-unsettling nature of cultural encoun- FMuch of humanity has experienced the feeling glance the images could be mis- with special needs ters. Ming Wong’s three-channel video, of being sequestered in their own unique ways taken for glimpses of the sky, taken — wove the other one In Love for the Mood, tweaks a scene in the last few months, since the outbreak from inside a cave or dormant vol- using yarns dyed in the from Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai’s of the novel coronavirus. My Body Holds Its cano. They are in fact chunks of mete- most vivid shades of blue, classic fi lm, In the Mood for Love. -

Classic Contemporary Contemporary Southeast Asian Art from the Singapore Art Museum Collection

CLASSIC CONTEMPORARY CONTEMPORARY SOUTHEAST ASIAN ART FROM THE SINGAPORE ART MUSEUM COLLECTION 29 JANUARY TO 2 MAY 2010 ADVISORY: THIS PUBLICATION CONTAINS IMAGES OF A GRAPHIC NATURE ABOUT THE EXHIBITION Classic Contemporary shines the spotlight on Singapore Art Museum’s most iconic contemporary artworks in its collection. By playfully asking what makes a work of art “classic” or “contemporary” — or “classic contemporary” — this accessible and quirky exhibition aims to introduce new audiences to the ideas and art forms of contemporary art. A stellar cast of painting, sculpture, video, photography and performance art from across Southeast Asia are brought together and given the red-carpet treatment, and the whole of the SAM 8Q building is transformed into a dramatic stage for these stars and icons. Yet beneath the glamour, many of the artworks also probe and prod serious issues — often asking critical and challenging questions about society, nation and the history of art itself. Since its inception in 1996, SAM has focused on collecting the works of artists practicing in the region, and many of these once-emerging artists have since established notable achievements on regional and international platforms. This exhibition marks the start of SAM’s new contemporary art programming centred on enabling artistic development through the creation of exhibition and programming platforms, as well as growing audiences for contemporary art. Classic Contemporary offers an opportunity to revisit major works by Suzann Victor, Matthew Ngui, Simryn Gill, Redza Piyadasa, Jim Supangkat, Nindityo Adipurnomo, Agnes Arellano, Agus Suwage, and Montien Boonma, among others. A full programme of curatorial lectures, artist presentations, moving image screenings and performances complete the classic contemporary experience. -

Every 23 Days

CONTENTS 11 Foreword 13 Introduction 15 Essay: Every 23 days... 17-21 Asialink Visual Arts Touring Exhibitions 1990-2010 23-86 Venue List 89-91 Index 92-93 Acknowledgements 94 FOREWORD 13 Asialink celebrates twenty years as a leader in Australia-Asia engagement through business, government, philanthropic and cultural partnerships. Part of the celebration is the publication of this booklet to commemorate the Touring Visual Arts Exhibitions Program which has been a central focus of Asialink’s work over this whole period. Artistic practice encourages dialogue between different cultures, with visual arts particularly able to transcend language barriers and create immediate and exciting rapport. Asialink has presented some of the best art of our time to large audiences in eighteen countries across Asia through exhibition and special projects, celebrating the strength and creativity on offer in Australia and throughout the region. The Australian Government, through the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, is pleased to provide support to Asialink as it continues to present the talents of artists of today to an ever increasing international audience. The Hon Stephen Smith MP Minister for Foreign Affairs INTRODUCTION 15 Every 23 Days: 20 Years Touring Asia documents the journey of nearly 80 Australian-based contemporary exhibitions’ history that have toured primarily through Asia as a part of the Asialink Touring Exhibition Program. This publication provides a chronological and in-depth overview of these exhibitions including special country focused projects and an introductory essay reflecting on the Program’s history. Since its inception in 1990, Asialink has toured contemporary architecture, ceramics, glass, installation, jewellery, painting, photography, textiles, video, works on paper to over 200 venues in Asia.