Parks: the International Journal of Protected Areas and Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4-12-2011 Event 1 Men, 400M Freestyle Jeugd/Senioren 02-12

Open Nederlandse Kampioenschappen Zwemmen Eindhoven, 2- - 4-12-2011 Event 1 Men, 400m Freestyle Jeugd/Senioren 02-12-2011 Results World Record 3:40.07 Paul Biedermann Rome (ITA) 26-07-2009 European Record 3:40.07 Paul Biedermann Rome (ITA) 26-07-2009 Nederlands Record Senioren 3:47.20 Pieter van den Hoogenband Amersfoort 20-04-2002 Nederlands Record Jeugd 3:55.65 Dion Dreesens Belgrado (SRB) 06-07-2011 Limiet OS 2012 Londen 3:47.90 Richttijd EK 2012 Antwerpen 3:51.49 Richttijd EJK 2012 Antwerpen 3:58.01 rank name club name time RT pts Jeugd 1 en 2 provisional results Louis Croenen ShaRK SHARK/133/94 4:00.24 +0,74 50m: 28.06 28.06 150m: 1:28.92 30.52 250m: 2:29.75 30.31 350m: 3:30.59 30.29 100m: 58.40 30.34 200m: 1:59.44 30.52 300m: 3:00.30 30.55 400m: 4:00.24 29.65 Lander Hendrickx BEST BEST/241/94 4:00.38 +0,73 50m: 28.04 28.04 150m: 1:28.85 30.61 250m: 2:29.60 30.31 350m: 3:30.64 30.46 100m: 58.24 30.20 200m: 1:59.29 30.44 300m: 3:00.18 30.58 400m: 4:00.38 29.74 Maarten Brzoskowski EIFFELswimmersPSV 199500769 4:05.97 +0,71 50m: 28.10 28.10 150m: 1:30.50 31.51 250m: 2:34.00 31.28 350m: 3:36.48 31.30 100m: 58.99 30.89 200m: 2:02.72 32.22 300m: 3:05.18 31.18 400m: 4:05.97 29.49 Lowie Vandamme Kon.Brugse Zwemkring BZK/463/94 4:08.38 +0,76 50m: 27.70 27.70 150m: 1:29.35 31.14 250m: 2:32.37 31.71 350m: 3:36.68 32.44 100m: 58.21 30.51 200m: 2:00.66 31.31 300m: 3:04.24 31.87 400m: 4:08.38 31.70 Conor Turner Aer Lingus 1994turn 4:10.39 +0,70 50m: 29.25 29.25 150m: 1:32.87 32.16 250m: 2:36.52 31.65 350m: 3:40.19 31.70 100m: 1:00.71 31.46 200m: -

A New Species of Mioeuoticus (Lorisiformes, Primates) from the Early Middle Miocene of Kenya

ANTHROPOLOGICAL SCIENCE Vol. 125(2), 59–65, 2017 A new species of Mioeuoticus (Lorisiformes, Primates) from the early Middle Miocene of Kenya Yutaka KUNIMATSU1*, Hiroshi TSUJIKAWA2, Masato NAKATSUKASA3, Daisuke SHIMIZU3, Naomichi OGIHARA4, Yasuhiro KIKUCHI5, Yoshihiko NAKANO6, Tomo TAKANO7, Naoki MORIMOTO3, Hidemi ISHIDA8 1Faculty of Business Administration, Ryukoku University, Kyoto 612-8577, Japan 2Department of Rehabilitation, Faculty of Medical Science and Welfare, Tohoku Bunka Gakuen University, Sendai 981-8551, Japan 3Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan 4Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Science and Technology, Keio University, Yokohama 223-8522, Japan 5Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Saga University, Saga 849-8501, Japan 6Graduate School of Human Sciences, Osaka University, Suita 565-0871, Japan 7Japan Monkey Center, Inuyama 484-0081, Japan 8Professor Emeritus, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan Received 24 November 2016; accepted 22 March 2017 Abstract We here describe a prosimian specimen discovered from the early Middle Miocene (~15 Ma) of Nachola, northern Kenya. It is a right maxilla that preserves P4–M3, and is assigned to a new species of the Miocene lorisid genus Mioeuoticus. Previously, Mioeuoticus was known from the Early Miocene of East Africa. The Nachola specimen is therefore the first discovery of this genus from the Middle Mi- ocene. The presence of a new lorisid species in the Nachola fauna indicates a forested paleoenvironment for this locality, consistent with previously known evidence including the abundance of large-bodied hominoid fossils (Nacholapithecus kerioi), the dominance of browsers among the herbivore fauna, and the presence of plenty of petrified wood. -

Construction Soil and Surface Water Management Sub Plan

Abergeldie Contractors Pty Ltd ABN: 47 004 533 519 5 George Young St, Regents Park NSW 2143 (P) 02 8717 7777 (F) 02 8717 7778 SYDNEY INTERNATIONAL SPEEDWAY Sydney Metro West CONTRACT No. 00013/11864 Construction Soil and Surface Water ManaGement Sub Plan 11 January 2021 T4129 - Sydney International Speedway – Construction Soil and Surface Water Management Sub Plan Revision Date: 11 January 2021 Page 2 of 77 THIS PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK Abergeldie ComPlex Infrastructure 5 George Young Street Regents Park NSW 2143 ABN 47 004 533 519 T4129 - Sydney International Speedway – Construction Soil and Surface Water Management Sub Plan Revision Date: 11 January 2021 Page 3 of 77 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 DOCUMENT CONTROL .................................................................................................... 5 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 8 2.1 CONTEXT ....................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................. 8 2.3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................. 8 2.4 IMPLEMENTATION OF THIS SUB-PLAN .................................................................... 13 2.5 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS OVERVIEW ..................................... 13 3 PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVES ...................................................................................... -

Visitcyprus.Com

Cyprus... inspiring champions “I found this training camp ideal. I must compliment the organisation and all involved for an excellent stay again. I highly recommend all professional teams to come to the island…” Gery Vink, Coach of Jong Ajax 1 Sports Tourism in Cyprus There are many reasons why athletes and sports lovers are drawn to the beautiful island of Cyprus… There’s the exceptional climate, the range of up-to-date sports facilities, the high-quality service industry, and the short travel times between city, sea and mountains. Cyprus offers a wide choice of sports facilities. From gyms Many international sports bodies have already recognized Cyprus to training grounds, from Olympic swimming pools to mountain as the ideal training destination. And it’s easy to see why National biking routes, there’s everything the modern sportsman or Olympic Committees from a number of countries have chosen woman could ask for. Cyprus as their pre-Olympic Games training destination. One of the world’s favourite holiday destinations, Cyprus also Medical care in Cyprus is of the highest standard, combining has an impressive choice of accommodation, from self-catering advanced equipment and facilities with the expertise of highly apartments to luxury hotels. When considering where to stay, it’s skilled practitioners. worth remembering that many hotels provide fully equipped The safe and friendly atmosphere also encourages athletes to fitness centres and health spas with qualified personnel - the bring families for an enjoyable break in the sun. Great restaurants, ideal way to train and relax. friendly cafes and great beaches make Cyprus the perfect place A gateway between Europe and the Middle East, Cyprus enjoys to unwind and relax. -

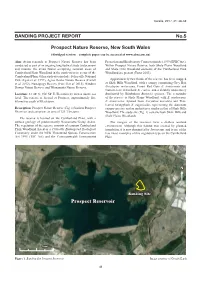

BANDING PROJECT REPORT No.5 Prospect Nature Reserve, New

Corella, 2017, 41: 48-52 BANDING PROJECT REPORT No.5 Prospect Nature Reserve, New South Wales (Abridged version – complete paper can be accessed at www.absa.asn.au) Aim: Avian research at Prospect Nature Reserve has been Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). conducted as part of an ongoing longitudinal study to document Within Prospect Nature Reserve, both Shale Plains Woodland and monitor the avian faunas occupying remnant areas of and Shale Hills Woodland elements of the Cumberland Plain Cumberland Plain Woodland in the north-western sector of the Woodland are present (Tozer 2003). Cumberland Plain. Other study sites include: Scheyville National Park (Egan et al. 1997), Agnes Banks Nature Reserve (Farrell Approximately two-thirds of the reserve has been mapped et al. 2012), Nurragingy Reserve (Farrell et al. 2015), Windsor as Shale Hills Woodland, with a canopy comprising Grey Box Downs Nature Reserve and Wianamatta Nature Reserve. Eucalyptus moluccana, Forest Red Gum E. tereticornis and Narrow-leaved Ironbark E. crebra, and a shrubby understorey Location: 33° 48′ S; 150° 54′ E. Elevation 61 metres above sea dominated by Blackthorn Bursaria spinosa. The remainder level. The reserve is located at Prospect, approximately five of the reserve is Shale Plains Woodland, with E. moluccana, kilometres south of Blacktown. E. tereticornis, Spotted Gum Corymbia maculata and Thin- leaved Stringybark E. eugenioides representing the dominant Description: Prospect Nature Reserve (Fig. 1) borders Prospect canopy species, and an understorey similar to that of Shale Hills Reservoir and comprises an area of 325.3 hectares. Woodland. The study site (Fig. 1) contains both Shale Hills and Shale Plains Woodlands. -

Tectono-Sedimentary Evolution of the Offshore Hydrocarbon Exploration Block 5, East Africa: Implication for Hydrocarbon Generation and Migration

Open Journal of Geology, 2018, 8, 819-840 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojg ISSN Online: 2161-7589 ISSN Print: 2161-7570 Tectono-Sedimentary Evolution of the Offshore Hydrocarbon Exploration Block 5, East Africa: Implication for Hydrocarbon Generation and Migration Ezekiel J. Seni1, Gabriel D. Mulibo1*, Giovanni Bertotti2 1Department of Geology, University of Dar es Salaam, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania 2Department of Geoscience and Civil engineering, Deft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherland How to cite this paper: Seni, E.J., Mulibo, Abstract G.D. and Bertotti, G. (2018) Tectono-Sedi- mentary Evolution of the Offshore Hydro- Sedimentary deposits in Block 5, offshore Tanzania basin have been imaged carbon Exploration Block 5, East Africa: using two-dimensional (2D) seismic data. The seismic data and well data re- Implication for Hydrocarbon Generation veal four tectonic units representing different tectonic events in relation to and Migration. Open Journal of Geology, 8, 819-840. structural styles, sedimentation and hydrocarbon potential evolved in Block 5. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojg.2018.88048 Results show that during Early to Late Jurassic, Block 5 was affected by the break-up of Gondwana and the drifting of Madagascar as evidenced by pat- Received: June 8, 2018 Accepted: August 1, 2018 terns of sediments and structural features. The chaotic and discontinuous Published: August 3, 2018 reflectors are characteristics features on the sediments pattern indicating a possible transitional setting following the breakup of Gondwana. From the Copyright © 2018 by authors and Late Cretaceous, Block 5 sits in more stable subsiding sag as the consequence Scientific Research Publishing Inc. -

Well-Groomed Predecessors Assigned to the Lorisid Species Nycticeboides Simpsoni

536 Nature Vol. 289 12 February 1981 from the late Miocene Siwalik deposits of Pakistan (some 7-10 million years old) Well-groomed predecessors assigned to the lorisid species Nycticeboides simpsoni. This newly from R. D. Martin discovered species definitely had a tooth RECONSTRUCTIONS of mammalian phy It has been claimed 7 that the tooth-comb in comb, and Rose et a/. have applied their logeny have depended heavily on dental small-bodied lemurs and lorises is too SEM procedure to the crowns of one evidence, since teeth are preferentially fragile to allow for its use in feeding, but canine and two incisors. These teeth closely preserved in the fossil record. As a rule fruit pulp provides no great resistance and resemble their counterparts in modern anterior teeth (especially incisors) are easily gums are usually collected in a semi-liquid lorisids and SEM examination revealed the lost in fossilization and most weight has state. It is therefore a moot point whether fine vertical grooves characteristic of use in been placed on the characteristics of cheek grooming or feeding was the primary grooming. Thus, the use of the lorisid teeth (premolars and molars). However, function of the tooth comb in lemurs and tooth-comb in grooming can be definitely there are some striking modifications of the lorises, but it is certain that both functions traced back at least 7 million years. Un lower anterior teeth among living are served in extant species. fortunately, though, feeding on gum or mammals and these provide not only useful Our understanding of the origin of soft fruit pulp is not known to leave diagnostic features but also valuable tooth-comb grooming has now been con characteristic wear patterns on the tooth functional clues. -

Mapping Known and Potential Karst Areas in the Northwest Territories, Canada

Mapping Known and Potential Karst Areas in the Northwest Territories, Canada Derek Ford, PGeo., PhD, FRSC. Emeritus Professor of Geography and Earth Sciences, McMaster University [email protected] For: Environment and Natural Resources, Government of the Northwest Territories August 2009 (i) Executive Summary The Goal of this Report is to Produce Maps of the Known and Potential Karst Landform Sites in the Northwest Territories (NWT) Karst landforms are those created by the dissolution of comparatively soluble rocks and the routing of the water (from rain or snowmelt) underground via caves rather than at the surface in river channels. The principal karst rocks are salt (so soluble that it is scarcely seen at the surface in the NWT), gypsum and anhydrite (solubility around 2500 mg/l of water), and limestone and dolomite (solubility around 250 -350 mg/l). All of these rock types are common and widespread amongst the sedimentary strata in the NWT. Surface karst landforms include: a) karren, which are spreads of individually small solution pits, shafts, and runnels that, collectively, may cover many hectares (limestone pavements); b) sinkholes of solutional, collapse, or other origin that can be tens to hundreds of metres in diameter and proportionally as deep. Sinkholes are considered the diagnostic karst landform worldwide; c) larger topographically closed depressions that may flood or drain seasonally, poljes if flat-floored, otherwise turloughs; d) extensive dry valleys and gorges, dry because their formative waters have been captured underground. All water sinking underground via karst landforms of all sizes drain quickly in comparison with all other types of groundwater because they are able to flow through solutionally enlarged conduits, termed caves where they are of enterable size. -

Oliva Vieira 2017.Pdf

Catena 149 (2017) 637–647 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Catena journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/catena Soil temperatures in an Atlantic high mountain environment: The Forcadona buried ice patch (Picos de Europa, NW Spain) Jesús Ruiz-Fernández a,⁎,MarcOlivab, Filip Hrbáček c, Gonçalo Vieira b, Cristina García-Hernández a a Department of Geography, University of Oviedo, Oviedo, Spain b Centre for Geographical Studies, Institute of Geography and Spatial Planning, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal c Department of Geography, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic article info abstract Article history: The present study focuses on the analysis of the ground and near-rock surface air thermal conditions at the Received 15 February 2016 Forcadona glacial cirque (2227 m a.s.l.) located in the Western Massif of the Picos de Europa, Spain. Temperatures Received in revised form 13 June 2016 have been monitored in three distinct geomorphological and topographical sites in the Forcadona area over the Accepted 27 June 2016 period 2006–11. The Forcadona buried ice patch is the remnant of a Little Ice Age glacier located in the bottom of a Available online 1 August 2016 glacial cirque. Its location in a deep cirque determines abundant snow accumulation, with snow cover between 8 and 12 months. The presence of snow favours stable soil temperatures and geomorphic stability. Similarly to Keywords: fi Soil temperatures other Cantabrian Mountains, the annual thermal regime of the soil is de ned by two seasonal periods (continu- Cirque wall temperatures ous thaw with daily oscillations and isothermal regime), as well as two short transition periods. -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

JAARVERSLAG 2008 Inhoud Contents

DOPINGAUTORITEIT JAARVERSLAG 2008 Inhoud Contents Voorwoord 3 Foreword 3 1 2008 in vogelvlucht 4 1 2008 in brief 4 2 Preventie en voorlichting 7 2 Prevention and education 7 3 Dopingcontroles 18 3 Doping controls 18 4 Internationale zaken 32 4 International Affairs 32 5 Juridische zaken 36 5 Legal Affairs 36 6 Wetenschappelijk onderzoek 40 6 Scientific research 40 7 Mens & organisatie 43 7 People & organisation 43 Bijlagen Annexes: 1 Financiële verantwoording 45 1 Financial 45 2 Samenstelling Bestuur, Raad van 2 Members of Board of Management, Advies en GDS-commissie 46 Advisory Board and TUE committee 46 3 Samenstelling Bureaupersoneel en 3 Office staff and list of doping control overzicht Dopingcontroleofficials 47 officials 47 4 Overzicht wetenschappelijk publicaties en 4 Overview of scientific publications and presentaties 48 presentations 48 5 Afkortingen 50 5 Abbreviations 50 DOPINGAUTORITEIT JAARVERSLAG 2008 2 Voorwoord Foreword Voor u ligt het derde Jaarverslag van de stichting This is the third Annual Report from the Anti- Anti-Doping Autoriteit Nederland. De stichting Doping Authority of the Netherlands. The orga- ontstond op 23 juni 2006 door een fusie van de nisation was established on 23 June 2006 with stichtingen Nederlands Centrum voor Doping- the merger of the Netherlands Centre for Doping vraagstukken en Doping Controle Nederland. Affairs and Doping Control Netherlands. De Dopingautoriteit heeft inmiddels bewezen dat The Doping Authority has now proven that housing het bijeen brengen van Preventie en Controle Prevention and Control in a single organisation binnen één organisatie een belangrijke stap is was an important step. The merger has allowed us geweest. -

In Vitro Culture of Luma Chequen from Vegetative Buds

Cien. Inv. Agr. 40(3):609-615. 2013 www.rcia.uc.cl BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH NOTE In vitro culture of Luma chequen from vegetative buds Héctor Mancilla1, Karla Quiroz1, Ariel Arencibia1, Basilio Carrasco2, and Rolando García-Gonzales1 1Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias y Forestales, Universidad Católica del Maule, Campus San Miguel. Casilla 617, Talca, Chile. 2Facultad de Agronomía, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Ave. Vicuña Mackenna 4860, Macul, Santiago, Chile. Abstract H. Mancilla, K. Quiroz, A. Arencibia, B. Carrasco, and R. García-Gonzales. 2013. In vitro culture of Luma chequen from vegetative buds. Cien. Inv. Agr. 40(3): 609-615. Luma chequen, a small tree or large shrub belonging to the Myrtaceae family, is endemic to South America and has medicinal, nutritional and ornamental potential. However, its native habitat is deteriorating gradually, and it is suffering from the effects of fragmentation that is being caused by the conversion of forest land to agricultural land and the natural expansion of monocultural plantations of exotic species, such as Pinus radiata. The purpose of this work is to develop an effective procedure for establishing in vitro cultures of the native Chilean species L. chequen. Aseptic nodal segments were evaluated after exposure to a disinfecting agent (1% solution of sodium hypochlorite) for different lengths of time. Murashige and Skoog (MS) or Woody Plant (WPM) culture media with 6-Bencilaminopurine (BAP) or 2-isopentenil adenine (2-iP) added to a concentration of 1 mg L-1 were evaluated. Although no significant differences were observed between cultures with and without additives, 40.43% of the explant cultures were successfully established.