Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patricia Murray Patricia Clum & Patricia M

PATRICIA MURRAY PATRICIA CLUM & PATRICIA M. MAKE-UP DESIGNER CANADIAN CITIZENSHIP & RESIDENCE / US RESIDENCE / IATSE 891 / ACFC HEAD OF DEPARTMENT FEATURE FILMS DIRECTOR/PRODUCER CAST THE ART OF RACING IN THE RAIN D: Simon Curtis Amanda Seyfried Fox 2000 Pictures P: Joannie Burstein, 2nd Unit Make-up Vancouver Patrick Dempsey, Tania Landau, Make-Up FX Artist Neal H. Moritz THE PACKAGE D: Jake Szymanski Daniel Doheny, Luke Spencer Roberts, Netflix EP: Shawn Williamson, Geraldine Viswanathan, Sadie Calvano, Brightlight Pictures & Jamie Goehring, Kevin Leeson, Eduardo Franco Red Hour Productions Haroon Saleem HOD & Make-Up FX Artist P: Ross Dinerstein, Nicky Weinstock, Ben Stiller, Anders Holm, Kyle Newacheck, Blake Anderson, Adam DeVine STATUS UPDATE D: Scott Speer Ross Lynch, Olivia Holt, Netflix P: Jennifer Gibgot, Dominic Rustam, Harvey Guillen, Famke Janssen, Offspring Entertainment & Adam Shankman, Shawn Williamson Wendi McLendon-Covey Brightlight Pictures HOD TOMORROWLAND D: Brad Bird Raffey Cassidy, Kathryn Hahn Walt Disney Pictures P: Damon Lindelof Make-Up Onset FX Supervisor Co-P: Bernie Bellew, Tom Peitzman PERCY JACKSON: D: Thor Freudenthal Missy Pyle, Yvette Nicole Brown, SEA OF MONSTERS P: Chris Columbus, Christopher Redman Fox 2000 Pictures Karen Rosenfelt, Michael Barnathan Make-Up FX Supervisor DAYDREAM NATION D: Michael Goldbach Personal Make-Up Artist to Kat Dennings Screen Siren Pictures EP: Tim Brown, Cameron Lamb HOD P: Trish Dolman, Christine Haebler, Michael Olsen, Simone Urdl THE TWILIGHT SAGA: ECLIPSE D: David Slade Ashley Greene, Bryce Dallas Howard, Summit Entertainment P: Wyck Godfrey, Greg Mooradian, Kellan Lutz Make-Up Artist Main Unit Karen Rosenfelt SLAP SHOT 2 D: Steve Boyum Stephen Baldwin, Gary Busey, Universal Pictures P: Ron French Callum Keith Rennie, Jessica Steen HOD JUST FRIENDS D: Roger Kumble Ryan Reynolds New Line Cinema P: Chris Bender, Bill Johnson, Make-Up FX Artist Michael Ohoven, J.C. -

Social Assessment January 2014

Government of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Regional Disaster Vulnerability Reduction Project (RDVRP) Social Assessment Report January 2014 Central Planning Division, Ministry of Finance and Economic Plann ing 1st Floor, Administrative Centre, Bay Street, Kingstown, St.V incent and the Grenadines Tel.: 784-457-1746 ● Fax: 784-456-2430 E-mail: [email protected] St. Vincent and the Grenadines 2 Social Assessment Regional Disaster Vulnerability Reduction Project Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations .................................................................................................... 5 Social Indicators ..................................................................................................................... 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 8 Objective of the Disaster Vulnerability Reduction Project ....................................................... 9 Socio-economic profile of St. Vincent and the Grenadines ............................................ 10 Country Description ................................................................................................................ 10 Weather and Climate .............................................................................................................. 10 Population Demographic Factors .......................................................................................... -

Abstract Department of Political Science Westfield

ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE WESTFIELD, ALWYN W BA. HONORS UNIVERSITY OF ESSEX, 1976 MS. LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON, 1977 THE IMPACT OF LEADERSHIP ON POLITICS AND POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT IN ST VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES UNDER EBENEZER THEODORE JOSHUA AND ROBERT MILTON CATO Committee Chair: Dr. F.SJ. Ledgister Dissertation dated May 2012 This study examines the contributions of Joshua and Cato as government and opposition political leaders in the politics and political development of SVG. Checklist of variable of political development is used to ensure objectivity. Various theories of leadership and political development are highlighted. The researcher found that these theories cannot fully explain the conditions existing in small island nations like SVG. SVG is among the few nations which went through stages of transition from colonialism to associate statehood, to independence. This had significant effect on the people and particularly the leaders who inherited a bankrupt country with limited resources and 1 persistent civil disobedience. With regards to political development, the mass of the population saw this as some sort of salvation for fulfillment of their hopes and aspirations. Joshua and Cato led the country for over thirty years. In that period, they have significantly changed the country both in positive and negative directions. These leaders made promises of a better tomorrow if their followers are prepared to make sacrifices. The people obliged with sacrifices, only to become disillusioned because they have not witnessed the promised salvation. The conclusions drawn from the findings suggest that in the process of competing for political power, these leaders have created a series of social ills in SVG. -

2013 Budget Speech

BUILDING A SUSTAINABLE, RESILIENT ECONOMY IN CHALLENGING TIMES BY DR. THE HON. RALPH E. GONSALVES PRIME MINISTER OF ST. VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES INTRODUCTION Mr. Speaker, Honourable Members, since our country’s attainment of independence on October 27, 1979, there have been 33 annual budgets. Robert Milton Cato, of blessed memory, crafted four of these budgets; Sir James Mitchell fashioned fourteen; Arnhim Eustace delivered three; and Budget 2013 is the twelfth which I am presenting. Each Minister of Finance has sought to make St. Vincent and the Grenadines a better place for its citizens; and to a greater or lesser extent each has succeeded despite the inherent limitations of our vulnerable small, multi-island economy and the awesome external challenges which confront us. Each national Budget has had its own peculiar or special frame against the backdrop of the general socio-economic condition. Each national Budget, too, is required to have its own focus, coherence, and developmental thrust. Each Budget is necessarily a house-keeping and developmental exercise, but much takes place, too, in the economy outside the Budget’s structured frame. For convenience, each possesses its own theme. For Budget 2013, the overarching theme is simple, yet profound: Building a Sustainable, Resilient Economy in Challenging Times. Mr. Speaker, it is inescapable that a Budget, especially in its developmental as distinct from its routine house-keeping function, is shaped by the Government’s thinking, explicit or implicit, in respect of the appropriate or relevant praxis – theory and practice – of economic development for micro-economies such as St. Vincent and the Grenadines. -

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines INTRODUCTION located on Saint Vincent, Bequia, Canouan, Mustique, and Union Island. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines is a multi-island Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, like most of state in the Eastern Caribbean. The islands have a the English-speaking Caribbean, has a British combined land area of 389 km2. Saint Vincent, with colonial past. The country gained independence in an area of 344 km2, is the largest island (1). The 1979, but continues to operate under a Westminster- Grenadines include 7 inhabited islands and 23 style parliamentary democracy. It is politically stable uninhabited cays and islets. All the islands are and elections are held every five years, the most accessible by sea transport. Airport facilities are recent in December 2010. Christianity is the Health in the Americas, 2012 Edition: Country Volume N ’ Pan American Health Organization, 2012 HEALTH IN THE AMERICAS, 2012 N COUNTRY VOLUME dominant religion, and the official language is fairly constant at 2.1–2.2 per woman. The crude English (1). death rate also remained constant at between 70 and In 2001 the population of Saint Vincent and 80 per 10,000 population (4). Saint Vincent and the the Grenadines was 102,631. In 2006, the estimated Grenadines has experienced fluctuations in its population was 100,271 and in 2009, it was 101,016, population over the past 20 years as a result of a decrease of 1,615 (1.6%) with respect to 2001. The emigration. According to the CIA World Factbook, sex distribution of the population in 2009 was almost the net migration rate in 2008 was estimated at 7.56 even, with males accounting for 50.5% (50,983) and migrants per 1,000 population (5). -

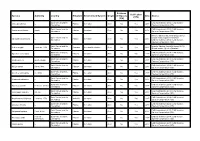

GRIIS Records of Verified Introduced and Invasive Species

Evidence Verification Species Authority Country Kingdom Environment/System Origin of Impacts Date Source (Y/N) (Y/N) Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Abrus precatorius L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Acacia auriculiformis Benth. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Invasive Species Specialist Group (2015). Saint Vincent and the Global Invasive Species Database. Adenanthera pavonina L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the Invasive Species Specialist Group (2015). Aedes aegypti Linnaeus, 1762 Animalia terrestrial/freshwater Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Global Invasive Species Database. Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Ageratum conyzoides L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Albizia procera Benth. (Roxb.) Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Albizia saman (Jacq.) Merr. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Aleurites moluccanus (L.) Willd. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Allamanda cathartica L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Alpinia purpurata K.Schum. (Vieill.) Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). -

CONTENTS Is on Our Youth, the Leaders of Tomorrow

St. Vincent & the Grenadines Association of Toronto Inc. Quarterly Newsletter October 2007 5555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESK This event was scheduled for late November but I have Greetings and best wishes to all members, friends and now learnt that it is postponed to March 1, 2008. We supporters of the Association. We thank you for your trust that this will be an opportunity for our young continued support as we strive to serve our community. people to look at the many opportunities that may become available to them. The last few months of the year are usually interesting ones for the Association as we look forward to As we look forward to the Annual General Meeting in wrapping up events held earlier in the year as well as January it would be useful if we would take some time planning for the ones to come including Independence out to prepare ourselves for it. Over the past few years Anniversary celebrations, the awarding of scholarships, the focus was just around the office of the president. the Children’s Christmas Party, the Christmas Hamper Getting persons to fill the other offices continue to be Project and to crown it off the preparation for the challenging and from time to time persons are forced to annual general meeting. accept these positions not merely because they are qualified to perform the role but because no one else On behalf of the executive I thank all those who have wanted the position. If we feel that there is need for volunteered their services and time so far to help us this organization to continue then we need to do what it accomplish what we have. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Canouan Estate Resort & Villas

MUSTIQUE THE ENT & GREN UNION ISLAND INC AD . V IN T ES CANOUAN S POINT JUPITER ESTATE RESORT & VILLAS ST. VINCENT MAYREAU CORBEC BAY HYAMBOOM BAY Canouan (pronounced ka-no-wan) is an island in the Grenadines, and one of nine inhabited and more than 20 uninhabited islands and cays which constitute Saint Vincent & The Grenadines. With a population of L’ANCE GUYAC BAY around 1,700, the small, at 3.5 miles (5.6km) by 1.25 miles (2km) yet inherently captivating island of Canouan BEQUIA BARBADOS R4 L’Ance Guyac is situated 25 miles (40km) South of Saint Vincent. Running along the Atlantic facing aspect of the island is 25 to 45 mins Beach Club PETIT MAHAULT BAY a barrier reef; whilst two bays separate its Southern side. The highest point on Canouan is Mount Royal. GRENADA 15 to 30 mins MUSTIQUE ST LUCIA 15 to 30 mins CANOUAN ST VINCENT SANDY LANE 10 mins YACHT CLUB LEGEND RESIDENCES TOBAGO CAYS K LITTLE BAY MAHAULT BEACH CANOUAN GOLF CLUB EVL TURTLE CREEK E31 IL SOGNO UNION ISLAND Canouan is accessible by POINT MOODY E27 BIG BLUE OCEAN E34 SILVER TURTLE air via five major gateways: CANOUAN ESTATE CHAPEL Barbados, St Lucia, Grenada, Martinique and ROAD mainland St Vincent. Its WHALING BAY airport features a 5900 ft runway, accommodating HIKING TRAIL private light, medium and some heavy jets for day or VILLAS RAMEAU BAY night landing. BOAT TRANSFERS Bellini’s Restaurant & Bar CARENAGE CANOTEN GV1 GV10 . La Piazza Restaurant & Bar E31 A4 CANOUAN ESTATE BOUNDARY R1 R2 A4 GV3 VILLAMIA GV14 THE BEACH HOUSE CATO BAY CS1 CS2 RUNWAY GV4 GOLF VILLA -

Delta Flyer 2011

1 Inh^ltsverzeichnis News vom Trekdinner / Impressum Seite 3 - 4 Trekdinner United V – Europapark Rust Seite 5 - 8 Klingolaus meint ... Seite 9 - 11 Bericht: Fedcon XX Seite 12 - 16 Trekkies treffen Winnetou, zum 7. Mal Seite 17 - 19 Captain’s Table 2011 Seite 20 - 22 Leonard Nimoy zum 80. Geburtstag Seite 23 - 32 William Shatner zum 80. Geburtstag Seite 33 - 36 Weihnachtslied Seite 37 - 38 Star Trek Romane aus dem Cross Cult-Verlag Seite 39 - 46 Star Trek Comics in Deutschland Seite 47 - 53 Wild Cards Seite 54 - 58 Grill-Trek 2011 Seite 59 - 61 Klingolausens‘ Lieblings-TV-Serien Seite 62 - 65 Coole neue Serien vom Klingolaus Seite 66 - 71 SPACEDOG´s Filme und DVDs in Kürze Seite 72 - 73 Film-Kritik: Das Kinojahr 2011 Seite 74 - 78 Film-Kritik: Tron & Tron Legacy Seite 79 - 82 Film-Kritik: Sucker Punch Seite 83 - 85 Film-Kritik: Pearl Harbor vs. Tora! Tora! Tora! Seite 86 - 89 DVD-Kritik: Nydenion Seite 90 - 92 Konzert-Kritiken Seite 93 - 94 Jubiläen, Geburtstage etc. Seite 95 2 News vom Trekdinner Mittelhessen Trekdinner Termine für 2012 Die folgenden Trekdinner-Termine sind vorläufig. Bitte achtet auf Änderungen auf unserer Internetseite. Die Trekdinner im Juni und Dezember entfallen zugunsten des Grill-Trek bzw. der X-Mas-Trek-Weihnachtsfeier. 14.01.: Wetzlar – 04.02.: Linden – 03.03.: Wetzlar – 07.04.: Linden – 05.05.: Wetzlar – 02.06.: Grill-Trek / Reinhardshain – 30.06.: Trekkies treffen Winnetou (Tagestermin mit BehindTheScenes) – 04.08.: Linden – 24./25.08.: Trekdinner United / ESA-ESOC Darmstadt / Filmmuseum Frankfurt – 01.09.: Wetzlar – 29.09.: Linden (vorverlegt w/RingCon) – 27.10.: Wetzlar (vorverlegt w/DarksideCon) – 01.12.: X-Mas Trek – 20 Jahre Trekdinner Mittelhessen (Location wird noch festgelegt) Location und Termine können sich im Einzelfall ändern! Änderungsinfos erscheinen auf der Website und ggf. -

SAINT VINCENT and the GRENADINES Pilot Program For

SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES PPCR PHASE 1 PROPOSAL SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR) PHASE ONE PROPOSAL 1 SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES PPCR PHASE 1 PROPOSAL Contents Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations .................................................................................. 5 Summary of Phase 1 Grant Proposal ................................................................................... 7 1.0 PROJECT BACKGROUND....................................................................................... 10 1.1 National Overview .................................................................................................. 11 1.1.1. Country Context ......................................................................................................... 11 2.0. Vulnerability Context .................................................................................................. 14 2.1 Climate .................................................................................................................... 14 2.1.1 Precipitation ............................................................................................................... 14 2.1.2 Temperature ................................................................................................................ 15 2.1.3 Sea Level Rise ............................................................................................................. 15 2.1.4 Climate Extremes ....................................................................................................... -

The University of Chicago the Creole Archipelago

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CREOLE ARCHIPELAGO: COLONIZATION, EXPERIMENTATION, AND COMMUNITY IN THE SOUTHERN CARIBBEAN, C. 1700-1796 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY TESSA MURPHY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2016 Table of Contents List of Tables …iii List of Maps …iv Dissertation Abstract …v Acknowledgements …x PART I Introduction …1 1. Creating the Creole Archipelago: The Settlement of the Southern Caribbean, 1650-1760...20 PART II 2. Colonizing the Caribbean Frontier, 1763-1773 …71 3. Accommodating Local Knowledge: Experimentations and Concessions in the Southern Caribbean …115 4. Recreating the Creole Archipelago …164 PART III 5. The American Revolution and the Resurgence of the Creole Archipelago, 1774-1785 …210 6. The French Revolution and the Demise of the Creole Archipelago …251 Epilogue …290 Appendix A: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of Dominica …301 Appendix B: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of St. Vincent …310 A Note on Sources …316 Bibliography …319 ii List of Tables 1.1: Respective Populations of France’s Windward Island Colonies, 1671 & 1700 …32 1.2: Respective Populations of Martinique, Grenada, St. Lucia, Dominica, and St. Vincent c.1730 …39 1.3: Change in Reported Population of Free People of Color in Martinique, 1732-1733 …46 1.4: Increase in Reported Populations of Dominica & St. Lucia, 1730-1745 …50 1.5: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in the Lesser Antilles, 1626-1762 …57 1.6: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in Jamaica & Saint-Domingue, 1526-1762 …58 2.1: Reported Populations of the Ceded Islands c.