Understanding the Digital Music Commodity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November-2015 Jukebox Songlist

Jukebox list ARTIST SONG TITLE Year 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 1978 112 DANCE WITH ME 2002 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 2000 2 PAC CHANGES 2000 2 PAC GHETTO GOSPEL 2000 28 DAYS AND APOLLO 440 SAY WHAT? 2001 28 DAYS RIP IT UP 2000 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU 2003 3 DOORS DOWN ITS NOT MY TIME 2008 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 2001 30 SECONDS TO MARS CLOSER TO THE EDGE 2010 30 SECONDS TO MARS THE KILL (BURY ME) 2006 360 FT GOSSLING BOYS LIKE YOU CLEAN 0 3LW NO MORE (BABY IMA DO RIGHT) 2001 3OH!3 DONT TRUST ME 2000 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY STARSTRUKK 2000 3OH3 DOUBLE VISION 0 3OH3 ft Kesha My First Kiss 0 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP 1992 411 THE DUMB 2004 411 THE FEAT GHOSTFACE KILAH ON MY KNEES 2000 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So perfect (Warning) 2014 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS 2003 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 2005 50 CENT FEAT JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE AYO TECHNOLOGY 2000 50 CENT FEAT. MOBB DEEP OUTTA CONTROL 2005 50 CENT IN DA CLUB 2003 50 CENT JUST A LIL BIT 2005 50 CENT P.I.M.P 2003 666 AMOKK 1999 98 DEGREES GIVE ME JUST ONE NIGHT (UNA NOCHE) 2000 A HA TAKE ON ME 1980 A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE 2002 AALIYAH TRY AGAIN 2000 AARON CARTER I WANT CANDY 2000 ABBA DANCING QUEEN 1976 ABBA MAMA MIA 0 ABBA ROCK ME 1979 ABBA WATERLOO 1974 ABC POISON ARROW 1982 ABS WHAT YOU GOT 2002 ACE OF BASE ALL THAT SHE WANTS (12 INCH VERSION) 2000 ACKER BILK STRANGER ON THE SHORE 0 ADAM BRAND KING OF THE ROAD 0 ADAM HARVEY THE HOUSE THAT JACK BUILT 0 ADAM LAMBERT FOR YOUR ENTERTAINMENT 0 ADAM LAMBERT IF I HAD YOU 0 ADELE SET FIRE TO THE RAIN 0 ADRIAN LUX TEENAGE CRIME 0 AEROSMITH I DONT WANT TO MISS A THING 1998 AEROSMITH JANIES GOT A GUN 1989 AFI MISS MURDER 2006 AFROJACK FT EVA SIMONS TAKE OVER CONTROL 2000 AFROMAN BECAUSE I GOT HIGH 2001 Agnes I Need You Now (Radio Edit) 0 AGNES RELEASE ME 2009 AIR LA FEMME DARGENT 1998 AKON ANGEL 2010 AKON DONT MATTER 2007 AKON FEAT COLBY ODONIS & KARDINAL BEAUTIFUL 2009 OFFISHALL Akon Feat Keri Hilson Oh Africa 2010 AKON FEAT SNOOP DOGG I WANNA LOV YOU 2000 AKON FEAT. -

1 Column Unindented

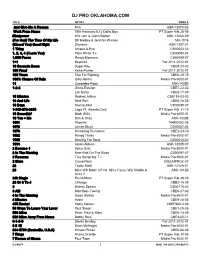

DJ PRO OKLAHOMA.COM TITLE ARTIST SONG # Just Give Me A Reason Pink ASK-1307A-08 Work From Home Fifth Harmony ft.Ty Dolla $ign PT Super Hits 28-06 #thatpower Will.i.am & Justin Bieber ASK-1306A-09 (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes MH-1016 (Kissed You) Good Night Gloriana ASK-1207-01 1 Thing Amerie & Eve CB30053-02 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's CB30094-04 1,000 Faces Randy Montana CB60459-07 1+1 Beyonce Fall 2011-2012-01 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray CBE9-23-02 100 Proof Kellie Pickler Fall 2011-2012-01 100 Years Five For Fighting CBE6-29-15 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Media Pro 6000-01 11 Cassadee Pope ASK-1403B 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan CBE7-23-03 Len Barry CBE9-11-09 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins CB5134-03-03 18 And Life Skid Row CBE6-26-05 18 Days Saving Abel CB30088-07 1-800-273-8255 Logic Ft. Alessia Cara PT Super Hits 31-10 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Media Pro 6000-01 19 You + Me Dan & Shay ASK-1402B 1901 Phoenix PHM1002-05 1973 James Blunt CB30067-04 1979 Smashing Pumpkins CBE3-24-10 1982 Randy Travis Media Pro 6000-01 1985 Bowling For Soup CB30048-02 1994 Jason Aldean ASK-1303B-07 2 Become 1 Spice Girls Media Pro 6000-01 2 In The Morning New Kids On The Block CB30097-07 2 Reasons Trey Songz ftg. T.I. Media Pro 6000-01 2 Stars Camp Rock DISCMPRCK-07 22 Taylor Swift ASK-1212A-01 23 Mike Will Made It Feat. -

"Weird Al" Yankovic

"Weird Al" Yankovic - Ebay Abba - Take A Chance On Me `M` - Pop Muzik Abba - The Name Of The Game 10cc - The Things We Do For Love Abba - The Winner Takes It All 10cc - Wall Street Shuffle Abba - Waterloo 1927 - Compulsory Hero ABC - Poison Arrow 1927 - If I Could ABC - When Smokey Sings 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings And Queens Ac Dc - Long Way To The Top 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings And Queens Ac Dc - Thunderstruck 30h!3 - Don't Trust Me Ac Dc - You Shook Me All Night Long 3Oh!3 feat. Katy Perry - Starstrukk AC/DC - Rocker 5 Star - Rain Or Shine Ac/dc - Back In Black 50 Cent - Candy Shop AC/DC - For Those About To Rock 50 Cent - Just A Lil' Bit AC/DC - Heatseeker A.R. Rahman Feat. The Pussycat Dolls - Jai Ho! (You AC/DC - Hell's Bells Are My Destiny) AC/DC - Let There Be Rock Aaliyah - Try Again AC/DC - Thunderstruck Abba - Chiquitita AC-DC - It's A Long Way To The Top Abba - Dancing Queen Adam Faith - The Time Has Come Abba - Does Your Mother Know Adamski - Killer Abba - Fernando Adrian Zmed (Grease 2) - Prowlin' Abba - Gimme Gimme Gimme (A Man After Midnight) Adventures Of Stevie V - Dirty Cash Abba - Knowing Me, Knowing You Aerosmith - Dude (Looks Like A Lady) Abba - Mamma Mia Aerosmith - Love In An Elevator Abba - Super Trouper Aerosmith - Sweet Emotion A-Ha - Cry Wolf Alanis Morissette - Not The Doctor A-Ha - Touchy Alanis Morissette - You Oughta Know A-Ha - Hunting High & Low Alanis Morrisette - I see Right Through You A-Ha - The Sun Always Shines On TV Alarm - 68 Guns Air Supply - All Out Of Love Albert Hammond - Free Electric Band -

As-Easy-As-A-Nuclear-War-Extract

First published in 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the copyright holder Copyright © Paul Cuddihy 2015 Published by Drone Publishing The right of Paul Cuddihy to be identified as the author of the work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design: Siobhann Caulfield Cover photograph: Tony Hamilton (Special thanks to Joe Hamilton for his enthusiasm and patience during the photo-shoot for the cover) Additional artwork: Tam McKinley ISBN: 1499337507 ISBN-13: 978-1499337501 Track List 1 Rio 1 2 Like An Angel 3 3 Skin Trade 13 4 All You Need Is Now 29 5 Come Undone 35 6 Hold Back The Rain 40 7 Planet Earth 43 8 Of Crime And Passion 66 9 Careless Memories 72 10 Sound Of Thunder 80 11 Girls On Film 89 12 Electric Barbarella 95 13 Save A Prayer 97 14 The Wild Boys 12 1 15 Someone Else Not Me 13 2 16 The Chauffeur 139 17 Hungry Like The Wolf 146 18 Last Chance On The Stairway 162 19 Violence of Summer (Love’s Taking Over) 164 20 The Reflex 174 21 Ordinary World 184 22 Lonely In Your Nightmare 192 23 A View To A Kill 20 1 24 Pressure Off 223 25 Is There Something I Should Know 231 PAUL CUDDIHY The cool thing about reading is that when you read a short story or you read something that takes your mind and expands where your thoughts can go, that's powerful. -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

The Observer Snhews March 7, 2002 2 Campus Security Log the Essence of Black History

ObserverObserverObserverTheThe Volume VIII, Issue 6 Southern New Hampshire University Thursday, March 7, 2002 McIninch Art Gallery Robert Frost Hall officially opens gets By Kara Dufour wired! Co-Editor in Chief By Matt Miville As some at SNHU followed Staff Writer their normal Friday evening routines, invited guests Over the past couple of mingled in the foyer of Rob- months people have mar- ert Frost Hall, drinking wine veled at the new buildings and soda and snacking on de- design. There is far more than licious treats. On Friday, Feb. meets the eye. In my efforts 22, at 7 p.m., the McIninch to find out what Robert Frost Art Gallery officially opened Hall was made of technologi- its doors, marking a special cally, this reporter set out to addition to SNHU. get some information about The McIninch Art Gallery what goes on behind the first opened its doors at a pre- scenes. What this reporter view on Thursday, Feb. 21, an found was impressive com- event for the entire SNHU puter labs, classrooms, com- campus. Approximately 125 mon areas, labs and the elu- students, faculty and staff sive new Trade Room. Every were the first to set eyes on day, hundreds of students the art works, with punch and pass by these technological cookies served in front of the wonders, but perhaps not re- gallery. alize what they contain. Although the Open House Dr. Stephanie Collins, assis- was a significant event, the Photo by Kara Dufour tant professor of information real show was on Feb. 22. In Pictured above are SNHU president Richard Gustafson (far left) with Douglas McIninch (far right) and his wife (middle left) and mother (middle right). -

Entertainment&Media

ENTERTAINMENT&MEDIA CJ E&M CJ CGV CJ HELLOVISION 1 CJ E&M is Asia’s No.1 integrated contents company, offering a variety of contents and platform services, including media, movies, live entertainment, and games. CJ E&M leverages synergies by converging a myriad of contents to lead the global Hallyu with new contents developed for one source for multi-use. 25 Korea’s first Multiplex Theater CGV boasts the largest number of cinemas in Korea and the greatest brand power. CGV has continued to develop a unique cinema experience so that the audience can watch a movie within the optimal environment. Cultureplex offers a new paradigm in movie theaters and is just one of the many innovations that CJ has brought to the movie industry. 41 CJ HelloVision is a leader in the smart platform market, delivering valuable contents and information to customers. CJ HelloVision provides you with advanced services fit for the new media environment. Its products include smart cable TV ‘hello tv Smart,’ digital cable TV ‘hello tv,’ fast speed internet ‘hello net,’ internet home telephone ‘hello fone,’ Korea’s No.1 budget phone service ‘hello mobile’ and the N screen service ‘tving.’ CJ E&M CJ CGV CJ HELLOVISION 2 3 BUSINESS OVERVIEW FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS CJ E&M Weight of each business Sales by year (Unit: billion won) CJ E&M Center, 66, Sangamsan-ro, Mapo-gu, Seoul as % of sales www.cjenm.com (As of 2013) 2013 1,716.1 2012 1,394.6 29% Asia’s No.1 Total Contents Company CJ E&M, 2011 1,279.2 45% creating a culture and a trend 12% Media Sales Profit by Year (Unit: billion won) Game 14% CJ E&M is the No.1 total contents company creating culture and trends. -

A Multi-Level Perspective Analysis of the Change in Music Consumption 1989-2014

A multi-level perspective analysis of the change in music consumption 1989-2014 by Richard Samuels Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Geography and Planning Cardiff University 2018 i Abstract This thesis seeks to examine the historical socio-technical transitions in the music industry through the 1990s and 2000s which fundamentally altered the way in which music is consumed along with the environmental resource impact of such transitions. Specifically, the investigation seeks to establish a historical narrative of events that are significant to the story of this transition through the use of the multi-level perspective on socio-technical transitions as a framework. This thesis adopts a multi-level perspective for socio-technical transitions approach to analyse this historical narrative seeking to identify key events and actors that influenced the transition as well as enhance the methodological implementation of the multi-level perspective. Additionally, this thesis utilised the Material Intensity Per Service unit methodology to derive several illustrative scenarios of music consumption and their associated resource usage to establish whether the socio-technical transitions experienced by the music industry can be said to be dematerialising socio-technical transitions. This thesis provides a number of original empirical and theoretical contributions to knowledge. This is achieved by presenting a multi-level perspective analysis of a historical narrative established using over 1000 primary sources. The research identifies, examines and discusses key events, actors and transition pathways denote the complex nature of dematerialising socio-technical systems as well as highlights specifically the influence different actors and actor groups can have on the pathways that transitions take. -

Artificial Realities; the Courtauld Institute of Art, 2016

Artificial 1 Realities Dates // 30.01.16 30.05.17 Sponsored by // 8 Curation Introduction Words // Jonathan Chapplow-Hansen ‘Imagination is not to avoid reality, nor is it resulting in five thematic lenses including description or an evocation of objects or Traces of Memory, Alterations in Light, situations, it is to say that poetry does not Falsehood & Fiction, Selected Paths and tamper with the world but moves it [...] it Transitional Spaces. The variety of ideational creates a new object, a play, a dance which is content is met with a heterogeneity in not a mirror up to nature but - ’ media as the fifty or so works take shape in sculpture, painting, site-specific installation, [Spring & All, William Carlos Williams] video and sound formats as well as in scent. In this passage by William Carlos Williams, A notable aspect of Artificial Realities is its the notion of solid reality is placed against use of non-purpose built exhibition spaces, imagination, and poetry is given an uncertain including halls, staircases, and niches. Herein location somewhere between these two we can see space as a signifier of movement, realms. The twelfth edition to the East flux, and liminality. Martin Buber and D.W Wing Biennial aims to explore this zone of Winnicot explored this notion of the ‘in- uncertainty, in an attempt to materialise between’ as a ‘meeting ground of potentiality what Williams chose not to articulate when and authenticity’,1 which one can understand he left his phrase unfinished and suspended. as the layering of expectation and reality - the It intends to investigate movement and continual vibrating threshold of subject and mobility in outwardly flat definitions, to find object. -

Atlantic Crossing

Artists like WARRENAI Tour Hard And Push Tap Could The Jam Band M Help Save The Music? ATLANTIC CROSSING 1/0000 ZOV£-10806 V3 Ii3V39 9N01 MIKA INVADES 3AV W13 OVa a STOO AlN33219 AINOW AMERICA IIII""1111"111111""111"1"11"11"1"Illii"P"II"1111 00/000 tOV loo OPIVW#6/23/00NE6TON 00 11910-E N3S,,*.***************...*. 3310NX0A .4 www.americanradiohistory.com "No, seriously, I'm at First Entertainment. Yeah, I know it's Saturday:" So there I was - 9:20 am, relaxing on the patio, enjoying the free gourmet coffee, being way too productive via the free WiFi, when it dawned on me ... I'm at my credit union. AND, it's Saturday morning! First Entertainment Credit Union is proud to announce the opening of our newest branch located at 4067 Laurel Canyon Blvd. near Ventura Blvd. in Studio City. Our members are all folks just like you - entertainment industry people with, you know... important stuff to do. Stop by soon - the java's on us, the patio is always open, and full - service banking convenience surrounds you. We now have 9 convenient locations in the Greater LA area to serve you. All branches are FIRSTENTERTAINMENT ¡_ CREDITUNION open Monday - Thursday 8:30 am to 5:00 pm and An Alternative Way to Bank k Friday 8:30 am to 6:00 pm and online 24/7. Plus, our Studio City Branch is also open on Saturday Everyone welcome! 9:00 am to 2:00 pm. We hope to see you soon. If you're reading this ad, you're eligible to join. -

Songs by Artist

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Artist www.adj2.com Title Title Title 10,000 Maniacs 50 Cent AC DC Because The Night Disco Inferno Stiff Upper Lip Trouble Me Just A Lil Bit You Shook Me All Night Long 10Cc P.I.M.P. Ace Of Base I'm Not In Love Straight To The Bank All That She Wants 112 50 Cent & Eminen Beautiful Life Dance With Me Patiently Waiting Cruel Summer 112 & Ludacris 50 Cent & The Game Don't Turn Around Hot & Wet Hate It Or Love It Living In Danger 112 & Supercat 50 Cent Feat. Eminem And Adam Levine Sign, The Na Na Na My Life (Clean) Adam Gregory 1975 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg And Young Crazy Days City Jeezy Adam Lambert Love Me Major Distribution (Clean) Never Close Our Eyes Robbers 69 Boyz Adam Levine The Sound Tootsee Roll Lost Stars UGH 702 Adam Sandler 2 Pac Where My Girls At What The Hell Happened To Me California Love 8 Ball & MJG Adams Family 2 Unlimited You Don't Want Drama The Addams Family Theme Song No Limits 98 Degrees Addams Family 20 Fingers Because Of You The Addams Family Theme Short Dick Man Give Me Just One Night Adele 21 Savage Hardest Thing Chasing Pavements Bank Account I Do Cherish You Cold Shoulder 3 Degrees, The My Everything Hello Woman In Love A Chorus Line Make You Feel My Love 3 Doors Down What I Did For Love One And Only Here Without You a ha Promise This Its Not My Time Take On Me Rolling In The Deep Kryptonite A Taste Of Honey Rumour Has It Loser Boogie Oogie Oogie Set Fire To The Rain 30 Seconds To Mars Sukiyaki Skyfall Kill, The (Bury Me) Aah Someone Like You Kings & Queens Kho Meh Terri -

BTS Love Yourself: Tear Throughout the Past Year Or So, K-Pop Group; BTS Has Been Blown up Like Crazy

BTS Love Yourself: Tear Throughout the past year or so, K-Pop group; BTS has been blown up like crazy. If you haven’t heard their name at least once, then I’m assuming you don’t keep up with the internet much. BTS has had so much worldwide success over the past year, that it’s hard to believe that they started off by advertising themselves with posters on the streets just 5 years ago. Their stage presence makes fans go wild, and have an amazing global following. They soon had became the most successful K-Pop act in U.S. history. Members from left to right: J-Hope, Jungkook, V (Taehyung), Jin, RM, Suga, Jimin If you are not familiar with K-Pop already, it is a genre of music that has originated in Korea. Korean Pop music has been popular internationally for a good few years, it’s not limited to just people in Korea. Every fan has their reason for liking the genre, maybe it’s the language, the sound, the style, or all of those things. Some people misinterpret fans as being ‘Koreaboos,’ which is internet slang for people who appropriate Korean culture and fetishize Koreans. Not all K-Pop fans are like that, many international fans respect Korean culture, and many are in fact against this kind of behaviour. Biographyoooooooooooooooooooooo ooooooooooooooooooooooo As for BTS fans, ARMY’s is the official fandom name, every K-Pop group or artist comes up with a name for their fans. BTS originally stood for ‘Bulletproof Boy Scouts,’ however throughout the years they have become comfortable with it standing for ‘Beyond The Scene.’ They debuted in 2013 along with their first album ‘2 Kool 4 Skool,’ simultaneously with the lead single in it, ‘No More Dream.’ The album was a big hit as it sold over 145,000 copies.