Table 4.3 Strategies for Ensuring a Rigorous Research Process (Based on Nicholls, 2009A)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Paris Region Is the #1 Destination on the Planet: with 50 Million Visitors Each Year, the Area Is Synonymous with “Art De Vivre”, Culture, Gastronomy and History

Saint-Denis Basilicum and Maison de la Légion d’Honneur © Plaine Commune, Direction du Développement Economique, SEPE, Som VOSAVANH-DEPLAGNE - Plain of Montesson © CSAGBS-EDesaux - La Défense Business district © 11h45 for Defacto - Campus © Ecole Polytechnique Paris/Saclay. J. Barande - © Ville d’Enghien-les-Bains - INSEAD Fontainebleau © Yann Piriou - Charenton-le-Pont – Ivry-sur-Seine © ParisEstMarne&Bois - Bassin de La Villette, Paris Plages © CRT Ile-de-France - Tripelon-Jarry Welcome to Paris Region Paris Region Facts and Figures 2020 lays out a panorama of the region’s economic dynamism and social life, Europe’s business positioning it among the leading regions in Europe and worldwide. & innovation With its fundamental key indicators, the brochure “Paris Region Facts and powerhouse Figures 2020” is a tool for decision and action for companies and economic stakeholders. It is useful to economic and political leaders of the region and to all those who want to have a global vision of this dynamic regional economy. Paris Region Facts and Figures 2020 is a collaborative publication produced by Choose Paris Region, L’Institut Paris Region and the Paris Île-de-France Regional Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Jardin_des_tuileries_Tour_Eiffel_01_tvb CRT IDF-Van Biesen Table of contents 5 Welcome to Paris Region 27 Digital Infrastructure 6 Overview 28 Real Estate 10 Population 30 Transport and Mobility 12 Economy and Business 32 Logistics 18 Employment 34 Meetings and Exhibitions 20 Education 36 Tourism and Quality of life 24 R&D and Innovation Paris Region Facts & Figures 2020 Welcome to Paris Region 5 A dynamic and A business fast-growing region and innovation powerhouse Paris Region, The Paris Region is a truly global region which accounts for 23.3% The highest GDP in the European of France’s workforce, 31% of Union (EU28) in billions of euros. -

Global Vs. Local-The Hungarian Retail Wars

Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) October 2015 Global Vs. Local-The Hungarian Retail Wars Charles S. Mayer Reza M. Bakhshandeh Central European University, Budapest, Hungary Key Words MNE’s, SME’s, Hungary, FMCG Retailing, Cooperatives, Rivalry Abstract In this paper we explore the impact of the ivasion of large global retailers into the Hungarian FMCG space. As well as giving the historical evolution of the market, we also show a recipe on how the local SME’s can cope with the foreign competition. “If you can’t beat them, at least emulate them well.” 1. Introduction Our research started with a casual observation. There seemed to be too many FMCG (Fast Moving Consumer Goods) stores in Hungary, compared to the population size, and the purchasing power. What was the reason for this proliferation, and what outcomes could be expected from it? Would the winners necessarily be the MNE’s, and the losers the local SME’S? These were the questions that focused our research for this paper. With the opening of the CEE to the West, large multinational retailers moved quickly into the region. This was particularly true for the extended food retailing sector (FMCG’s). Hungary, being very central, and having had good economic relations with the West in the past, was one of the more attractive markets to enter. We will follow the entry of one such multinational, Delhaize (Match), in detail. At the same time, we will note how two independent local chains, CBA and COOP were able to respond to the threat of the invasion of the multinationals. -

Trade for Development Centre - BTC (Belgian Development Agency)

Trade for Development Centre - BTC (Belgian Development Agency) 1 Trade for Development Centre - BTC (Belgian Development Agency) Author: Facts Figures Future, http://www.3xf.nl Managing Editor: Carl Michiels © BTC, Belgian Development Agency, 2011. All rights reserved. The content of this publication may be reproduced after permission has been obtained from BTC and provided that the source is acknowledged. This publication of the Trade for Development Centre does not necessarily represent the views of BTC. Photo courtesy: © iStockphoto/Mediaphotos Cover: © CTB Josiane Droeghag 2 Trade for Development Centre - BTC (Belgian Development Agency) ......................................................................................................................................... 3 ............................................................................................................................ 4 .................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Consumption .................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Imports .............................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Supplying markets ........................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Exports ............................................................................................................................. -

The Healthy Incentive for Pre-Schools (HIP) Project

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Science 2013-2 The Healthy Incentive for Pre-schools (HIP) Project: The Development, Validation, Evaluation and Implementation of an Healthy Incentive Scheme in the Irish Full Day Care Pre-school Setting. Charlotte Johnston Molloy [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/sciendoc Part of the Biochemical Phenomena, Metabolism, and Nutrition Commons, and the Medical Nutrition Commons Recommended Citation Johnston Molloy, C. (2013). The healthy incentive for pre-schools (HIP) project: the development, validation, evaluation and implementation of an healthy incentive scheme in the Irish full day care pre- school setting. Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/D7WW20 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Science at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License The Healthy Incentive for Pre-schools (HIP) project: The development, validation, evaluation and implementation of an healthy incentive scheme in the Irish full day care pre-school setting. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Charlotte Johnston Molloy B.Sc. (Hum. Nut. & Diet.), M.Sc. (Agr.) Supervisors Dr. John M. Kearney Prof. Nóirín Hayes Dr. Clare Corish School of Biological Sciences Dublin Institute of Technology February 2013 i Abstract While many children are now cared for outside the home, inadequate nutrition and physical activity practices in pre-schools have been reported. -

Producer/Retailer Contractual Relationships in the Fishing Sector : Food Quality, Procurement and Prices Stéphane Gouin, Erwan Charles, Jean-Pierre Boude

Producer/retailer Contractual Relationships in the fishing sector : food quality, procurement and prices Stéphane Gouin, Erwan Charles, Jean-Pierre Boude, . European Association of Fisheries Economists To cite this version: Stéphane Gouin, Erwan Charles, Jean-Pierre Boude, . European Association of Fisheries Economists. Producer/retailer Contractual Relationships in the fishing sector : food quality, procurement and prices. 16th Annual Conference of the European Association of Fisheries Economists, European Association of Fisheries Economists (EAFE). FRA., Apr 2004, Roma, Italy. 15 p. hal-02311416 HAL Id: hal-02311416 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02311416 Submitted on 7 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License t XVIth Annual EAFE Conference, Roma, April 5-7th 2004 I EAFE, Romu, April 5-7th 2004 Producer/retailer Contractual Relationships in the fTshing sector : food quality, procurement and prices Gouin 5., Charles 8., Boude fP. Agrocampus Rennes Département d'Economie Rurale et Gestion 65, rue de Saint Brieuc CS 84215 F 35042 Rennes cedex gouin@agrocampus-rennes. fr boude@agrocampus-rennes. fr and *CEDEM Université de Bretagne Occidentale 12, rue de Kergoat BP 816 29285 Brest cedex erwan. -

Romania: Retail Food Sector

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 2/6/2017 GAIN Report Number: RO1703 Romania Post: Bucharest Retail Food Sector Report Categories: Retail Foods Approved By: Russ Nicely Prepared By: Ioana Stoenescu Report Highlights: Over the last three years, Romania has seen strong positive growth, with encouraging developments in the economic and policy areas, becoming one of the most attractive markets in Southeastern Europe. After just a few notable events during 2015, the Romanian retail market experienced remarkable growth in 2016 reaching 2,000 stores operated by international retailers. As modern retail systems grow, exports of U.S. processed and high value foods to Romania will continue to expand. In 2015 U.S. agri- food exports to Romania increased by 45 percent from U.S. $96 million to U.S. $139 million over the last year. Romania's food sector is expected to be among the regional best performers during the next five years, with promising market prospects for U.S. exporters such as tree nuts, distilled spirits and wines. General Information: I. MARKET SUMMARY General Information Romania has been a member of the EU since 2007 and a member of NATO since 2004. Within the 28 EU countries, Romania has the seventh largest population, with 19.5 million inhabitants. Romania is presently a market with outstanding potential, a strategic location, and an increasingly solid business climate. Although there is the need for an exporter to evaluate the market in order to assess the business opportunities, exporting to Romania is steadily becoming less challenging than in previous years in terms of the predictability of the business environment. -

Health Inequalities on the Island of Ireland - an Agenda for Change!

Report of the conference on "Creating connections": health inqualities on the island of Ireland - an agenda for change! Item Type Report Authors Public Health Alliance Ireland (PHAI) Rights PHAI Download date 02/10/2021 01:15:44 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10147/45051 Find this and similar works at - http://www.lenus.ie/hse Report of the conference on “Creating Connections” Health inequalities on the island of Ireland - an agenda for change! Maynooth, November 2004 CREATING CONNECTIONS Perspectives on Health Inequalities on the island of Ireland Organising and Editorial Committee: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thomas Quigley Chair The Public Health Alliance Ireland (PHAI) and the (safefood, the Food Safety Promotion Board) Northern Ireland Public Health Alliance (NIPHA) in association with the Institute of Public Health in Ireland Monica-Anne Brennan (IPHI) would like to thank the organising committee for (Public Health Alliance Ireland) their work in organising the conference from which these perspectives are derived and for their assistance Majella McCloskey in editing this report. Special thanks to the chairs of (Association of Chief Officers of Voluntary the conference sessions: Owen Metcalfe, Brigid Quirke, Organisations NI) Majella McCloskey, Martin Higgins, Thomas Quigley and Diarmuid O’Donovan. Gary McFarlane (Chartered Institute of Environmental Health NI) The Alliances acknowledge the financial support received for the Creating Connections Conference and Aisling O’Connor this publication from the following: (Institute of Public Health -

Retail Food Sector Retail Foods France

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 9/13/2012 GAIN Report Number: FR9608 France Retail Foods Retail Food Sector Approved By: Lashonda McLeod Agricultural Attaché Prepared By: Laurent J. Journo Ag Marketing Specialist Report Highlights: In 2011, consumers spent approximately 13 percent of their budget on food and beverage purchases. Approximately 70 percent of household food purchases were made in hyper/supermarkets, and hard discounters. As a result of the economic situation in France, consumers are now paying more attention to prices. This situation is likely to continue in 2012 and 2013. Post: Paris Author Defined: Average exchange rate used in this report, unless otherwise specified: Calendar Year 2009: US Dollar 1 = 0.72 Euros Calendar Year 2010: US Dollar 1 = 0.75 Euros Calendar Year 2011: US Dollar 1 = 0.72 Euros (Source: The Federal Bank of New York and/or the International Monetary Fund) SECTION I. MARKET SUMMARY France’s retail distribution network is diverse and sophisticated. The food retail sector is generally comprised of six types of establishments: hypermarkets, supermarkets, hard discounters, convenience, gourmet centers in department stores, and traditional outlets. (See definition Section C of this report). In 2011, sales within the first five categories represented 75 percent of the country’s retail food market, and traditional outlets, which include neighborhood and specialized food stores, represented 25 percent of the market. In 2011, the overall retail food sales in France were valued at $323.6 billion, a 3 percent increase over 2010, due to price increases. -

The Childhood Overweight and Obesity on the Island of Ireland Campaign Ireland

Let’s Take on Childhood Obesity – The Childhood Overweight and Obesity on the Island of Ireland campaign Ireland Which ‘life stage’ for CVDs prevention targets the intervention? Childhood and Adolescence Short description of the intervention: Let’s Take on Childhood Obesity is a public health campaign to take on childhood obesity aimed at parents of children aged 2-12 years, on the island of Ireland. This is a 3 year campaign and was launched in October 2013 by Safefood i in partnership with the Health Service Executive 2 and Healthy Ireland Framework 3 in the Republic of Ireland and the ‘Fitter Futures for All’ Implementation Plan in Northern Ireland 4. The campaign urges parents to make practical changes to everyday lifestyle habits which would make a big difference to their children’s future health. Tackling Childhood Obesity is a public health priority, with 1 in 4 children across the Island of Ireland carrying excess weight. There is growing evidence underlining the impact of obesity on short and long term health and well-being. Children who are obese are likely to remain obese through to adulthood. The aim of the campaign is to halt the rise in both overweight and obesity levels in children by: 1. Communicating practical solutions that parents can adopt in order to tackle the everyday habits that are associated with excess weight gain in childhood. 2. Maintaining awareness of the health challenges posed by excess weight in childhood and the negative impact this can have on the quality of life. The campaign provides parents with practical solutions that they can adopt to tackle everyday habits associated with excess weight. -

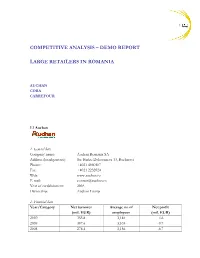

DEMO Competitive Analysis Retail

COMPETITIVE ANALYSIS – DEMO REPORT LARGE RETAILERS IN ROMANIA AUCHAN CORA CARREFOUR 1.1 Auchan 1. General data Company name: Auchan Romania SA Address (headquarters): Str. Barbu Delavrancea 13, Bucharest Phone: +4021 4080107 Fax: +4021 2232024 Web: www.auchan.ro E-mail: [email protected] Year of establishment: 2005 Ownership: Auchan Group 2. Financial data Year/Category Net turnover Average no of Net profit (mil. EUR) employees (mil. EUR) 2010 355.8 3,184 -4.6 2009 307.6 3,103 -9.7 2008 278.4 3,156 -6.7 A FRD Center Market Entry Services Demo Publication www.market-entry.ro 3. Key persons Name Position Contact details Mr. Patrick Espasa General Director Email: [email protected] Mr. Tiberiu Danetiu Marketing Director Email: [email protected] Ms. Mariana Dragan Communication Manager Email: [email protected] Tel: +4 021 4080294 4. Brief profile Auchan Romania is part of the French Group Auchan. Auchan opened its first hypermarket on the Romanian market in 2006. This store is located in Bucharest (in the Titan area) and has the surface of over 16,000 sqm. The store records a daily traffic of 30,000 – 45,000 persons and registers the biggest sales in the Auchan network in Romania. At present, Auchan has nine hypermarkets in Romania, located in Bucharest (two stores – in the Titan and Militari areas), Pitesti, Targu Mures, Cluj Napoca, Suceava, Timisoara, Constanta and Craiova. The Auchan hypermarket in Cluj Napoca was opened in November 2007, with an investment of 40 million EUR. The store is located in the Iulius Mall, has the surface of some 10,000 sqm and offers over 45,000 products. -

THE OPERATION of the NORTH-SOUTH IMPLEMENTATION BODIES John Coakley, Brian Ó Caoindealbháin and Robin Wilson

Centre for International Borders Research Papers produced as part of the project Mapping frontiers, plotting pathways: routes to North-South cooperation in a divided island THE OPERATION OF THE NORTH-SOUTH IMPLEMENTATION BODIES John Coakley, Brian Ó Caoindealbháin and Robin Wilson Project supported by the EU Programme for Peace and Reconciliation and administered by the Higher Education Authority, 2004-06 WORKING PAPER 6 THE OPERATION OF THE NORTH-SOUTH IMPLEMENTATION BODIES John Coakley, Brian Ó Caoindealbháin and Robin Wilson MFPP Working Papers No. 6, 2006 (also printed as IBIS working paper no. 56) © the authors, 2006 Mapping Frontiers, Plotting Pathways Working Paper No. 6, 2006 (also printed as IBIS working paper no. 56) Institute for British-Irish Studies Institute of Governance Geary Institute for the Social Sciences Centre for International Borders Research ISSN 1649-0304 University College Dublin Queen’s University Belfast ABSTRACT BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION THE OPERATION OF THE NORTH-SOUTH John Coakley is an associate professor of politics at University College Dublin. He IMPLEMENTATION BODIES has edited or co-edited Changing shades of orange and green: redefining the union and the nation in contemporary Ireland (UCD Press, 2002); The territorial manage- This paper examines the functioning of the North-South implementation bodies for- ment of ethnic conflict (2nd ed., Frank Cass, 2003); From political violence to nego- mally created in 1999 over the first five years of their existence. It reviews the politi- tiated settlement: the winding path to peace in twentieth century Ireland (UCD Press, cal and administrative difficulties that delayed their establishment as functioning in- 2004); and Politics in the Republic of Ireland (4th ed., Routledge, 2004). -

Groupe Auchan / Magyar Hipermarket Regulation (Ec)

EN Case No COMP/M.6506 - GROUPE AUCHAN / MAGYAR HIPERMARKET Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EC) No 139/2004 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 18/04/2012 In electronic form on the EUR-Lex website under document number 32012M6506 Office for Publications of the European Union L-2985 Luxembourg EUROPEAN COMMISSION In the published version of this decision, some Brussels, 18.04.2012 information has been omitted pursuant to Article C(2012) 2682 17(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 concerning non-disclosure of business secrets and other confidential information. The omissions are PUBLIC VERSION shown thus […]. Where possible the information omitted has been replaced by ranges of figures or a general description. MERGER PROCEDURE To the notifying party: Dear Sir/Madam, Subject: Case No COMP/M.6506 - GROUPE AUCHAN / MAGYAR HIPERMARKET Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) of Council Regulation No 139/20041 1. On 9 March 2012, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 by which Auchan Magyarország Kft (Hungary), belonging to the Groupe Auchan SA ("Auchan", France) acquires within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation sole control of Magyar Hipermarket Kereskedelmi Kft. ("Magyar Hipermarket", Hungary) by way of purchase of shares.2 Auchan is designated hereinafter as the "Notifying Party", Auchan and Magyar Hipermarket together as the "Parties". 1 OJ L 24, 29.1.2004, p. 1 ("the Merger Regulation"). With effect from 1 December 2009, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ("TFEU") has introduced certain changes, such as the replacement of "Community" by "Union" and "common market" by "internal market".