Causes and Consequences of Food Retailing Innovation in Developing Countries: Supermarkets in Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Paris Region Is the #1 Destination on the Planet: with 50 Million Visitors Each Year, the Area Is Synonymous with “Art De Vivre”, Culture, Gastronomy and History

Saint-Denis Basilicum and Maison de la Légion d’Honneur © Plaine Commune, Direction du Développement Economique, SEPE, Som VOSAVANH-DEPLAGNE - Plain of Montesson © CSAGBS-EDesaux - La Défense Business district © 11h45 for Defacto - Campus © Ecole Polytechnique Paris/Saclay. J. Barande - © Ville d’Enghien-les-Bains - INSEAD Fontainebleau © Yann Piriou - Charenton-le-Pont – Ivry-sur-Seine © ParisEstMarne&Bois - Bassin de La Villette, Paris Plages © CRT Ile-de-France - Tripelon-Jarry Welcome to Paris Region Paris Region Facts and Figures 2020 lays out a panorama of the region’s economic dynamism and social life, Europe’s business positioning it among the leading regions in Europe and worldwide. & innovation With its fundamental key indicators, the brochure “Paris Region Facts and powerhouse Figures 2020” is a tool for decision and action for companies and economic stakeholders. It is useful to economic and political leaders of the region and to all those who want to have a global vision of this dynamic regional economy. Paris Region Facts and Figures 2020 is a collaborative publication produced by Choose Paris Region, L’Institut Paris Region and the Paris Île-de-France Regional Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Jardin_des_tuileries_Tour_Eiffel_01_tvb CRT IDF-Van Biesen Table of contents 5 Welcome to Paris Region 27 Digital Infrastructure 6 Overview 28 Real Estate 10 Population 30 Transport and Mobility 12 Economy and Business 32 Logistics 18 Employment 34 Meetings and Exhibitions 20 Education 36 Tourism and Quality of life 24 R&D and Innovation Paris Region Facts & Figures 2020 Welcome to Paris Region 5 A dynamic and A business fast-growing region and innovation powerhouse Paris Region, The Paris Region is a truly global region which accounts for 23.3% The highest GDP in the European of France’s workforce, 31% of Union (EU28) in billions of euros. -

Global Vs. Local-The Hungarian Retail Wars

Journal of Business and Retail Management Research (JBRMR) October 2015 Global Vs. Local-The Hungarian Retail Wars Charles S. Mayer Reza M. Bakhshandeh Central European University, Budapest, Hungary Key Words MNE’s, SME’s, Hungary, FMCG Retailing, Cooperatives, Rivalry Abstract In this paper we explore the impact of the ivasion of large global retailers into the Hungarian FMCG space. As well as giving the historical evolution of the market, we also show a recipe on how the local SME’s can cope with the foreign competition. “If you can’t beat them, at least emulate them well.” 1. Introduction Our research started with a casual observation. There seemed to be too many FMCG (Fast Moving Consumer Goods) stores in Hungary, compared to the population size, and the purchasing power. What was the reason for this proliferation, and what outcomes could be expected from it? Would the winners necessarily be the MNE’s, and the losers the local SME’S? These were the questions that focused our research for this paper. With the opening of the CEE to the West, large multinational retailers moved quickly into the region. This was particularly true for the extended food retailing sector (FMCG’s). Hungary, being very central, and having had good economic relations with the West in the past, was one of the more attractive markets to enter. We will follow the entry of one such multinational, Delhaize (Match), in detail. At the same time, we will note how two independent local chains, CBA and COOP were able to respond to the threat of the invasion of the multinationals. -

Trade for Development Centre - BTC (Belgian Development Agency)

Trade for Development Centre - BTC (Belgian Development Agency) 1 Trade for Development Centre - BTC (Belgian Development Agency) Author: Facts Figures Future, http://www.3xf.nl Managing Editor: Carl Michiels © BTC, Belgian Development Agency, 2011. All rights reserved. The content of this publication may be reproduced after permission has been obtained from BTC and provided that the source is acknowledged. This publication of the Trade for Development Centre does not necessarily represent the views of BTC. Photo courtesy: © iStockphoto/Mediaphotos Cover: © CTB Josiane Droeghag 2 Trade for Development Centre - BTC (Belgian Development Agency) ......................................................................................................................................... 3 ............................................................................................................................ 4 .................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Consumption .................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Imports .............................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Supplying markets ........................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Exports ............................................................................................................................. -

Producer/Retailer Contractual Relationships in the Fishing Sector : Food Quality, Procurement and Prices Stéphane Gouin, Erwan Charles, Jean-Pierre Boude

Producer/retailer Contractual Relationships in the fishing sector : food quality, procurement and prices Stéphane Gouin, Erwan Charles, Jean-Pierre Boude, . European Association of Fisheries Economists To cite this version: Stéphane Gouin, Erwan Charles, Jean-Pierre Boude, . European Association of Fisheries Economists. Producer/retailer Contractual Relationships in the fishing sector : food quality, procurement and prices. 16th Annual Conference of the European Association of Fisheries Economists, European Association of Fisheries Economists (EAFE). FRA., Apr 2004, Roma, Italy. 15 p. hal-02311416 HAL Id: hal-02311416 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02311416 Submitted on 7 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License t XVIth Annual EAFE Conference, Roma, April 5-7th 2004 I EAFE, Romu, April 5-7th 2004 Producer/retailer Contractual Relationships in the fTshing sector : food quality, procurement and prices Gouin 5., Charles 8., Boude fP. Agrocampus Rennes Département d'Economie Rurale et Gestion 65, rue de Saint Brieuc CS 84215 F 35042 Rennes cedex gouin@agrocampus-rennes. fr boude@agrocampus-rennes. fr and *CEDEM Université de Bretagne Occidentale 12, rue de Kergoat BP 816 29285 Brest cedex erwan. -

Romania: Retail Food Sector

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 2/6/2017 GAIN Report Number: RO1703 Romania Post: Bucharest Retail Food Sector Report Categories: Retail Foods Approved By: Russ Nicely Prepared By: Ioana Stoenescu Report Highlights: Over the last three years, Romania has seen strong positive growth, with encouraging developments in the economic and policy areas, becoming one of the most attractive markets in Southeastern Europe. After just a few notable events during 2015, the Romanian retail market experienced remarkable growth in 2016 reaching 2,000 stores operated by international retailers. As modern retail systems grow, exports of U.S. processed and high value foods to Romania will continue to expand. In 2015 U.S. agri- food exports to Romania increased by 45 percent from U.S. $96 million to U.S. $139 million over the last year. Romania's food sector is expected to be among the regional best performers during the next five years, with promising market prospects for U.S. exporters such as tree nuts, distilled spirits and wines. General Information: I. MARKET SUMMARY General Information Romania has been a member of the EU since 2007 and a member of NATO since 2004. Within the 28 EU countries, Romania has the seventh largest population, with 19.5 million inhabitants. Romania is presently a market with outstanding potential, a strategic location, and an increasingly solid business climate. Although there is the need for an exporter to evaluate the market in order to assess the business opportunities, exporting to Romania is steadily becoming less challenging than in previous years in terms of the predictability of the business environment. -

Retail Food Sector Retail Foods France

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 9/13/2012 GAIN Report Number: FR9608 France Retail Foods Retail Food Sector Approved By: Lashonda McLeod Agricultural Attaché Prepared By: Laurent J. Journo Ag Marketing Specialist Report Highlights: In 2011, consumers spent approximately 13 percent of their budget on food and beverage purchases. Approximately 70 percent of household food purchases were made in hyper/supermarkets, and hard discounters. As a result of the economic situation in France, consumers are now paying more attention to prices. This situation is likely to continue in 2012 and 2013. Post: Paris Author Defined: Average exchange rate used in this report, unless otherwise specified: Calendar Year 2009: US Dollar 1 = 0.72 Euros Calendar Year 2010: US Dollar 1 = 0.75 Euros Calendar Year 2011: US Dollar 1 = 0.72 Euros (Source: The Federal Bank of New York and/or the International Monetary Fund) SECTION I. MARKET SUMMARY France’s retail distribution network is diverse and sophisticated. The food retail sector is generally comprised of six types of establishments: hypermarkets, supermarkets, hard discounters, convenience, gourmet centers in department stores, and traditional outlets. (See definition Section C of this report). In 2011, sales within the first five categories represented 75 percent of the country’s retail food market, and traditional outlets, which include neighborhood and specialized food stores, represented 25 percent of the market. In 2011, the overall retail food sales in France were valued at $323.6 billion, a 3 percent increase over 2010, due to price increases. -

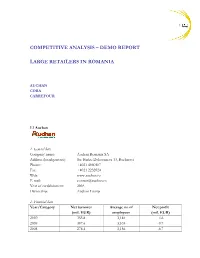

DEMO Competitive Analysis Retail

COMPETITIVE ANALYSIS – DEMO REPORT LARGE RETAILERS IN ROMANIA AUCHAN CORA CARREFOUR 1.1 Auchan 1. General data Company name: Auchan Romania SA Address (headquarters): Str. Barbu Delavrancea 13, Bucharest Phone: +4021 4080107 Fax: +4021 2232024 Web: www.auchan.ro E-mail: [email protected] Year of establishment: 2005 Ownership: Auchan Group 2. Financial data Year/Category Net turnover Average no of Net profit (mil. EUR) employees (mil. EUR) 2010 355.8 3,184 -4.6 2009 307.6 3,103 -9.7 2008 278.4 3,156 -6.7 A FRD Center Market Entry Services Demo Publication www.market-entry.ro 3. Key persons Name Position Contact details Mr. Patrick Espasa General Director Email: [email protected] Mr. Tiberiu Danetiu Marketing Director Email: [email protected] Ms. Mariana Dragan Communication Manager Email: [email protected] Tel: +4 021 4080294 4. Brief profile Auchan Romania is part of the French Group Auchan. Auchan opened its first hypermarket on the Romanian market in 2006. This store is located in Bucharest (in the Titan area) and has the surface of over 16,000 sqm. The store records a daily traffic of 30,000 – 45,000 persons and registers the biggest sales in the Auchan network in Romania. At present, Auchan has nine hypermarkets in Romania, located in Bucharest (two stores – in the Titan and Militari areas), Pitesti, Targu Mures, Cluj Napoca, Suceava, Timisoara, Constanta and Craiova. The Auchan hypermarket in Cluj Napoca was opened in November 2007, with an investment of 40 million EUR. The store is located in the Iulius Mall, has the surface of some 10,000 sqm and offers over 45,000 products. -

Groupe Auchan / Magyar Hipermarket Regulation (Ec)

EN Case No COMP/M.6506 - GROUPE AUCHAN / MAGYAR HIPERMARKET Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EC) No 139/2004 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 18/04/2012 In electronic form on the EUR-Lex website under document number 32012M6506 Office for Publications of the European Union L-2985 Luxembourg EUROPEAN COMMISSION In the published version of this decision, some Brussels, 18.04.2012 information has been omitted pursuant to Article C(2012) 2682 17(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 concerning non-disclosure of business secrets and other confidential information. The omissions are PUBLIC VERSION shown thus […]. Where possible the information omitted has been replaced by ranges of figures or a general description. MERGER PROCEDURE To the notifying party: Dear Sir/Madam, Subject: Case No COMP/M.6506 - GROUPE AUCHAN / MAGYAR HIPERMARKET Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) of Council Regulation No 139/20041 1. On 9 March 2012, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 by which Auchan Magyarország Kft (Hungary), belonging to the Groupe Auchan SA ("Auchan", France) acquires within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation sole control of Magyar Hipermarket Kereskedelmi Kft. ("Magyar Hipermarket", Hungary) by way of purchase of shares.2 Auchan is designated hereinafter as the "Notifying Party", Auchan and Magyar Hipermarket together as the "Parties". 1 OJ L 24, 29.1.2004, p. 1 ("the Merger Regulation"). With effect from 1 December 2009, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ("TFEU") has introduced certain changes, such as the replacement of "Community" by "Union" and "common market" by "internal market". -

FRENCH MARKET PRESENTATION for : FEVIA from : Sophie Delcroix – Elise Deroo – Green Seed France Date : 19Th June, 2014

FRENCH MARKET PRESENTATION For : FEVIA From : Sophie Delcroix – Elise Deroo – Green Seed France Date : 19th June, 2014 FEVIA 1 I. GREEN SEED GROUP : WHO WE ARE II. MARKET BACKGROUND AND CONSUMER TRENDS III. THE FRENCH RETAIL SECTOR IV. KEY RETAILERS PROFILES V. FOODSERVICE VI. KEY LEARNINGS VII. CASE STUDIES FEVIA 2 Green Seed Group Having 25 years of experience, the Green Seed Group is a unique international network of 11 offices in Europe, North America and Australia, specializing in the food & beverage sector OUR MISSION Advise both French and foreign food and beverage companies or marketing boards, on how to develop a sustainable and profitable position abroad Green Seed France help you to develop your activity in France using our in-depth knowledge of the local food and beverage market and our established contacts within the trade FEVIA 3 A growing and unique international network Germany (+ A, CH) The Netherlands Scandinavia U.S.A./Canada Great Britain Belgium France Portugal Spain Italy 11 offices covering 18 countries Australasia FEVIA 4 The Green Seed model Over the last decade, one of the most important trends in the French food & drink trade has been for retailers to deal with their suppliers on a direct line. Green Seed France has developed its business model around this trend. We act as business facilitators ensuring that every step of the process is managed with maximum efficiency. From first market visit, to launch as well as the ongoing relationship that follows. We offer a highly cost-effective solution of “flexible local sales and marketing management support” aimed at adding value. -

Netherlands Retail Foods Benelux Food Retail Market

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 1/26/2010 GAIN Report Number: NL0002 Netherlands Retail Foods Benelux Food Retail Market Approved By: Stephen Huete Prepared By: Marcel Pinckaers Report Highlights: Despite the current economic situation, the turnover of the Benelux food retail market in 2009 was €52.7 billion, 4.4% higher than previous year. In addition, the food retail market continues to consolidate further. Post: The Hague Author Defined: Section I. Market Summary Benelux Food Retail Market Approximately 80 percent of the Dutch food retail outlets are full service supermarkets, operating on floor space between 500 and 1,500 square meters located downtown and in residential areas. The remaining 20 percent includes superstores located in industrial parks, convenience stores near human traffic and department stores. In Belgium, full service supermarkets, like Colruyt and AD Delhaize, account for an estimated 75 percent of the market. The share of superstores and convenience stores in Belgium is higher than in the Netherlands, an estimated 25%. In Luxembourg, full service supermarkets like Cactus, Alvo and Match dominate the market as well. In all three markets, independent food retail stores are increasingly leaving the scene. On-going consolidation in the retail market, changing consumer demands and shrinking margins seem to drive this trend. The top 3 biggest retailers in the Netherlands, Albert Heijn, C1000, and Jumbo [1] , have a market share of 56 percent. The market for discounters like Aldi and Lidl has stabilized around 15%. -

Trends in the Top Retail Trade in Romania

Scientific Papers Series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development Vol. 19, Issue 1, 2019 PRINT ISSN 2284-7995, E-ISSN 2285-3952 TRENDS IN THE TOP RETAIL TRADE IN ROMANIA Agatha POPESCU University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Bucharest, 59 Marasti Boulevard, District 1, 011464, Bucharest Romania, Phone: +40213182564, Fax: +40213182888, Email: [email protected] Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The paper analyzed the retail trade in Romania during the last decade, 2008-2017, pointing out the performance achieved by the top 10 retailers Kaufland, Carrefour, Lidl, Auchan, Mega Image, Profi, Metro, Selgros, Rewe and Cora Hypermarket, based on the number of stores, turnover, net profit, market share and average number of employees. Romanian market proved to be a good business environment for retailers as long as consumption is increasing determined by the growth of wages and reduction of VAT. Both hypermarkets, supermarkets, discount stores and minimarkets have appeared on Romania's map and their number continue to grow as expected in the near future. The number of square meters commercial space per inhabitant is enough high as long as Romanians like shopping. For this reason, the retailers have to develop new strategies to strengthen their business and cover much better consumers' needs. Important efforts should be made to develop the minimarket network in the smaller cities and even in the rural localities, the commercial space should be modernized and offer a pleasant and attractive environment for shopping, e-commerce should be extended as a modern purchasing alternative, the offer should be diversified including more Romanian products as preferred by consumers, organic products should be more visible on the shelves which have to offer healthy products to the clients, a more intensive advertising should be useful for a better information of the consumers and for increasing sales and profit of the retailers. -

168-014 Bakucz Ferto.Indd

Agric.Econ – Czech, 61, 2015 (11): 511–521 Original Paper doi: 10.17221/168/2014-AGRICECON Empirical tests of sale theories: Hungarian milk prices Zoltán BAKUCS1,2, Imre FERTŐ1,2,3 1Institute of Economics, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary 2Corvinus University of Budapest, Budapest, Hungary 3University of Kaposvár, Kaposvár, Hungary Abstract: Th e paper tests various predictions of the sale theory literature, using the retailer specifi c price data in Hungary. Besides being set in a New Member State, characterised by rather diff erent history of retailing than the established market economies, one of the main innovations of this paper is the comparative assessment of price promotions of two homoge- nous, every-day products diff erent only with respect to their perishability: one litre boxed and one litre durable fl uid milk. Using a battery of empirical techniques from the simple summary statistics, the distribution analysis to the discrete choice models and the co-integration, there is concluded that competing theory predictions on price distributions are not accep- ted. Also the Hypothesis that manufacturers determine timing of sales is rejected. Th e results do not confi rm that durable goods should have a qualitatively diff erent pricing pattern than perishable products. When the temporal order of sales is considered, the estimations support the Hypothesis of alternate sales. In sum, the predictions of the existing retail sales models only partly confi rm certain empirical aspects of price promotions. Key words: chain level prices, milk products, price promotion, sale theories Periodic price reductions, or price promotions, manufacturers or rather retailers decide on sales, constitute a widely observed phenomenon in retail- pricing strategies followed by retailers etc.).