Interview with Louis Nirenberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

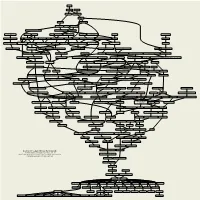

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction To

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Springer-V erlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH Richard Courant • Fritz John Introd uction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Reprint of the 1989 Edition Springer Originally published in 1965 by Interscience Publishers, a division of John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Reprinted in 1989 by Springer-Verlag New York, Inc. Mathematics Subject Classification (1991): 26-XX, 26-01 Cataloging in Publication Data applied for Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Courant, Richard: Introduction to calcu1us and analysis / Richard Courant; Fritz John.- Reprint of the 1989 ed.- Berlin; Heidelberg; New York; Barcelona; Hong Kong; London; Milan; Paris; Singapore; Tokyo: Springer (Classics in mathematics) VoL 1 (1999) ISBN 978-3-540-65058-4 ISBN 978-3-642-58604-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-58604-0 Photograph of Richard Courant from: C. Reid, Courant in Gottingen and New York. The Story of an Improbable Mathematician, Springer New York, 1976 Photograph of Fritz John by kind permission of The Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York ISSN 1431-0821 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved. whether the whole or part of the material is concemed. specifically the rights of trans1ation. reprinting. reuse of illustrations. recitation. broadcasting. reproduction on microfilm or in any other way. and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted onlyunder the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9.1965. in its current version. and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer-Verlag. Violations are Iiable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. -

Notices of the American Mathematical

OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY VOLUMf 12, NUMBER 2 ISSUE NO. 80 FEBRUARY 1965 cNotiaiJ OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Edited by John W. Green and Gordon L. \Yalker CONTENTS MEETINGS Calendar of Meetings o o o o o o o o o • o o • o o o o o o o • o 0 o 0 o 0 • 0 • 0 0 • 0 0 184 Program of the Meeting in New York. o 0 o 0 o 0 0 • 0 o o o 0 0 0 0 • 0 0 0 0 0 • 185 Abstracts for the Meeting- Pages 209-216 PRELIMINARY ANNOUNCEMENTS OF MEETINGS • o o o o o o o o • o 0 • 0 • 0 • • • 188 ACTIVITIES OF OTHER ASSOCIATIONS •••• o o. o o o o • o o o •• o 0 0 0. o 0 0 0 0 191 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR • o ••••• o o • o o o o o • o ••• o •••• o o o •• o o • o o 192 MEMORANDA TO MEMBERS List of Retired Mathematicians 190 Increase in Page Charges o o ••• o •• o • o o o •••••• 0 ••• 0 0 0 •• 0 0 0 0 194 Journals in Microform • o •••• o 0 ••• o • o ••• 0 •• o ••••• 0 •• 0 • • • • 194 Backlog of Mathematics Research Journals 0 0 0. 0. 0 ••• 0 •• 0 •• 0.. 195 Corporate Members ••••••••••••• 0 • 0 0 0 0 •• 0 0 • 0 •• 0 0 •• 0 ••• 0 201 ASSISTANTSHIPS AND FELLOWSHIPS IN MATHEMATICS 1965-1966 0 ••• 0 • 0 196 NEW AMS PUBLICATIONS • o •• o •• o •••• o • o o ••••• o o o •• o o •• o • o • o • 197 PERSONAL ITEMS .••••• o •• o. -

Prizes and Awards Session

PRIZES AND AWARDS SESSION Wednesday, July 12, 2021 9:00 AM EDT 2021 SIAM Annual Meeting July 19 – 23, 2021 Held in Virtual Format 1 Table of Contents AWM-SIAM Sonia Kovalevsky Lecture ................................................................................................... 3 George B. Dantzig Prize ............................................................................................................................. 5 George Pólya Prize for Mathematical Exposition .................................................................................... 7 George Pólya Prize in Applied Combinatorics ......................................................................................... 8 I.E. Block Community Lecture .................................................................................................................. 9 John von Neumann Prize ......................................................................................................................... 11 Lagrange Prize in Continuous Optimization .......................................................................................... 13 Ralph E. Kleinman Prize .......................................................................................................................... 15 SIAM Prize for Distinguished Service to the Profession ....................................................................... 17 SIAM Student Paper Prizes .................................................................................................................... -

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Emigration Of

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 51/2011 DOI: 10.4171/OWR/2011/51 Emigration of Mathematicians and Transmission of Mathematics: Historical Lessons and Consequences of the Third Reich Organised by June Barrow-Green, Milton-Keynes Della Fenster, Richmond Joachim Schwermer, Wien Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze, Kristiansand October 30th – November 5th, 2011 Abstract. This conference provided a focused venue to explore the intellec- tual migration of mathematicians and mathematics spurred by the Nazis and still influential today. The week of talks and discussions (both formal and informal) created a rich opportunity for the cross-fertilization of ideas among almost 50 mathematicians, historians of mathematics, general historians, and curators. Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 01A60. Introduction by the Organisers The talks at this conference tended to fall into the two categories of lists of sources and historical arguments built from collections of sources. This combi- nation yielded an unexpected richness as new archival materials and new angles of investigation of those archival materials came together to forge a deeper un- derstanding of the migration of mathematicians and mathematics during the Nazi era. The idea of measurement, for example, emerged as a critical idea of the confer- ence. The conference called attention to and, in fact, relied on, the seemingly stan- dard approach to measuring emigration and immigration by counting emigrants and/or immigrants and their host or departing countries. Looking further than this numerical approach, however, the conference participants learned the value of measuring emigration/immigration via other less obvious forms of measurement. 2892 Oberwolfach Report 51/2011 Forms completed by individuals on religious beliefs and other personal attributes provided an interesting cartography of Italian society in the 1930s and early 1940s. -

Selected Papers

Selected Papers Volume I Arizona, 1968 Peter D. Lax Selected Papers Volume I Edited by Peter Sarnak and Andrew Majda Peter D. Lax Courant Institute New York, NY 10012 USA Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 11Dxx, 35-xx, 37Kxx, 58J50, 65-xx, 70Hxx, 81Uxx Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lax, Peter D. [Papers. Selections] Selected papers / Peter Lax ; edited by Peter Sarnak and Andrew Majda. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-387-22925-6 (v. 1 : alk paper) — ISBN 0-387-22926-4 (v. 2 : alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—United States. 2. Mathematics—Study and teaching—United States. 3. Lax, Peter D. 4. Mathematicians—United States. I. Sarnak, Peter. II. Majda, Andrew, 1949- III. Title. QA3.L2642 2004 510—dc22 2004056450 ISBN 0-387-22925-6 Printed on acid-free paper. © 2005 Springer Science+Business Media, Inc. All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, Inc., 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed in the United States of America. -

Implications for Understanding the Role of Affect in Mathematical Thinking

Mathematicians and music: Implications for understanding the role of affect in mathematical thinking Rena E. Gelb Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Rena E. Gelb All Rights Reserved Abstract Mathematicians and music: Implications for understanding the role of affect in mathematical thinking Rena E. Gelb The study examines the role of music in the lives and work of 20th century mathematicians within the framework of understanding the contribution of affect to mathematical thinking. The current study focuses on understanding affect and mathematical identity in the contexts of the personal, familial, communal and artistic domains, with a particular focus on musical communities. The study draws on published and archival documents and uses a multiple case study approach in analyzing six mathematicians. The study applies the constant comparative method to identify common themes across cases. The study finds that the ways the subjects are involved in music is personal, familial, communal and social, connecting them to communities of other mathematicians. The results further show that the subjects connect their involvement in music with their mathematical practices through 1) characterizing the mathematician as an artist and mathematics as an art, in particular the art of music; 2) prioritizing aesthetic criteria in their practices of mathematics; and 3) comparing themselves and other mathematicians to musicians. The results show that there is a close connection between subjects’ mathematical and musical identities. I identify eight affective elements that mathematicians display in their work in mathematics, and propose an organization of these affective elements around a view of mathematics as an art, with a particular focus on the art of music. -

Homogenization 2001, Proceedings of the First HMS2000 International School and Conference on Ho- Mogenization

in \Homogenization 2001, Proceedings of the First HMS2000 International School and Conference on Ho- mogenization. Naples, Complesso Monte S. Angelo, June 18-22 and 23-27, 2001, Ed. L. Carbone and R. De Arcangelis, 191{211, Gakkotosho, Tokyo, 2003". On Homogenization and Γ-convergence Luc TARTAR1 In memory of Ennio DE GIORGI When in the Fall of 1976 I had chosen \Homog´en´eisationdans les ´equationsaux d´eriv´eespartielles" (Homogenization in partial differential equations) for the title of my Peccot lectures, which I gave in the beginning of 1977 at Coll`egede France in Paris, I did not know of the term Γ-convergence, which I first heard almost a year after, in a talk that Ennio DE GIORGI gave in the seminar that Jacques-Louis LIONS was organizing at Coll`egede France on Friday afternoons. I had not found the definition of Γ-convergence really new, as it was quite similar to questions that were already discussed in control theory under the name of relaxation (which was a more general question than what most people mean by that term now), and it was the convergence in the sense of Umberto MOSCO [Mos] but without the restriction to convex functionals, and it was the natural nonlinear analog of a result concerning G-convergence that Ennio DE GIORGI had obtained with Sergio SPAGNOLO [DG&Spa]; however, Ennio DE GIORGI's talk contained a quite interesting example, for which he referred to Luciano MODICA (and Stefano MORTOLA) [Mod&Mor], where functionals involving surface integrals appeared as Γ-limits of functionals involving volume integrals, and I thought that it was the interesting part of the concept, so I had found it similar to previous questions but I had felt that the point of view was slightly different. -

Fritz John, 1910–1994 an Elegant Construction of the Fundamental Solution for Par- Fritz John Died in New Rochelle, NY, on February 10, 1994

people.qxp 3/16/99 5:26 PM Page 255 Mathematics People Mathematics of the AMS and the Society for Industrial and Moser Receives Wolf Prize Applied Mathematics (1968), the Craig Watson Medal of Jürgen Moser of the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (1969), the John von in Zürich will receive the 1994–1995 Wolf Prize in Mathe- Neumann Lectureship of SIAM (1984), the L. E. J. Brouwer matics. The noted German mathematician will be honored Medal (1984), an Honorary Professorship at the Instituto with the $100,000 award by the Israel-based Wolf Foun- de Matematica Pura e Applicada (1989), and an honorary dation for his “fundamental work on stability in Hamil- doctorate from the University of Bochum (1990). Moser is tonian mechanics and his profound and influential con- a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. tributions to nonlinear differential equations.” The 1994–1995 Wolf Prizes will be presented in March —from Wolf Foundation News Release by the president of Israel, Ezer Weizman, at the Knesset (Parliament) building in Jerusalem. A total of $600,000 will be awarded for outstanding achievements in the fields Aisenstadt Prizes Announced of agriculture, chemistry, physics, medicine, the arts, and mathematics. The Wolf Foundation was established by the The Centre de Recherches Mathématiques in Montreal has late Ricardo Wolf, an inventor, diplomat, and philanthropist. announced that the third and fourth André Aisenstadt Among Moser’s most important achievements is his Mathematics Prizes have been awarded to Nigel D. Hig- role in the development of KAM (Kolmogorov-Arnold- son of Pennsylvania State University and Michael J. -

Scientific Curriculum of Emanuele Haus

Scientific curriculum of Emanuele Haus October 25, 2018 Personal data • Date of birth: 31st July 1983 • Place of birth: Milan (ITALY) • Citizenship: Italian • Gender: male Present position • (December 2016 - present): Fixed-term researcher (RTD-A) at the University of Naples “Federico II”. Previous positions • (November 2016 - December 2016): Research collaborator (“co.co.co.”) at the University of Roma Tre, within the ERC project “HamPDEs – Hamil- tonian PDEs and small divisor problems: a dynamical systems approach” (principal investigator: Michela Procesi). • (August 2014 - July 2016): “assegno di ricerca” (post-doc position) at the University of Naples “Federico II”, within the STAR project “Water waves, PDEs and dynamical systems with small divisors” (principal investi- gator: Pietro Baldi) and the ERC project “HamPDEs – Hamiltonian PDEs and small divisor problems: a dynamical systems approach” (principal in- vestigator: Michela Procesi, local coordinator: Pietro Baldi). • (March 2013 - July 2014): “assegno di ricerca” (post-doc position) at the University of Rome “La Sapienza”, within the ERC project “HamPDEs – Hamiltonian PDEs and small divisor problems: a dynamical systems approach” (principal investigator: Michela Procesi). • (January 2012 - December 2012): post-doc position at the Labora- toire de Mathématiques “Jean Leray” (Nantes), within the ANR project “HANDDY – Hamiltonian and Dispersive equations: Dynamics” (principal investigator: Benoît Grébert). Abilitazione Scientifica Nazionale (National Scientific Qualification) • In 2018, I have obtained the Italian Abilitazione Scientifica Nazionale for the rôle of Associate Professor in the sector 01/A3 (Mathematical Analysis, Probability and Mathematical Statistics). Qualification aux fonctions de Maître de Conférences • In 2013, I have obtained the French Qualification aux fonctions de Maître de Conférences in Mathematics (section 25 of CNRS). -

The Mathematical Heritage of Henri Poincaré

http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/pspum/039.1 THE MATHEMATICAL HERITAGE of HENRI POINCARE PROCEEDINGS OF SYMPOSIA IN PURE MATHEMATICS Volume 39, Part 1 THE MATHEMATICAL HERITAGE Of HENRI POINCARE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND PROCEEDINGS OF SYMPOSIA IN PURE MATHEMATICS OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 39 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SYMPOSIUM ON THE MATHEMATICAL HERITAGE OF HENRI POINCARfe HELD AT INDIANA UNIVERSITY BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA APRIL 7-10, 1980 EDITED BY FELIX E. BROWDER Prepared by the American Mathematical Society with partial support from National Science Foundation grant MCS 79-22916 1980 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 01-XX, 14-XX, 22-XX, 30-XX, 32-XX, 34-XX, 35-XX, 47-XX, 53-XX, 55-XX, 57-XX, 58-XX, 70-XX, 76-XX, 83-XX. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: The Mathematical Heritage of Henri Poincare\ (Proceedings of symposia in pure mathematics; v. 39, pt. 1— ) Bibliography: p. 1. Mathematics—Congresses. 2. Poincare', Henri, 1854—1912— Congresses. I. Browder, Felix E. II. Series: Proceedings of symposia in pure mathematics; v. 39, pt. 1, etc. QA1.M4266 1983 510 83-2774 ISBN 0-8218-1442-7 (set) ISBN 0-8218-1449-4 (part 2) ISBN 0-8218-1448-6 (part 1) ISSN 0082-0717 COPYING AND REPRINTING. Individual readers of this publication, and nonprofit librar• ies acting for them are permitted to make fair use of the material, such as to copy an article for use in teaching or research. Permission is granted to quote brief passages from this publication in re• views provided the customary acknowledgement of the source is given.