WWF Global Marine Turtle Strategy 23 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arcus Foundation 2012 Annual Report the Arcus Foundation Is a Leading Global Foundation Advancing Pressing Social Justice and Conservation Issues

ConservationSocialJustice Arcus Foundation 2012 Annual Report The Arcus Foundation is a leading global foundation advancing pressing social justice and conservation issues. The creation of a more just and humane world, based on diversity, Arcus works to advance LGBT equality, as well as to conserve and protect the great apes. equality, and fundamental respect. L etter from Jon Stryker 02 L etter from Kevin Jennings 03 New York, U.S. Cambridge, U.K. Great Apes 04 44 West 28th Street, 17th Floor Wellington House, East Road New York, NY 10001 U.S. Cambridge CB1 1BH, U.K. Great Apes–Grantees 22 Phone +1.212.488.3000 Phone +44.1223.451050 Fax + 1. 212.488.3010 Fax +44.1223.451100 Strategy 24 [email protected] [email protected] F inancials / Board & Staff ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: © Emerson, Wajdowicz Studios / NYC / www.DesignEWS.com EDITORIAL TEAM: Editor, Sebastian Naidoo Writers, Barbara Kancelbaum & Susanne Morrell 25 THANK YOU TO OUR GRANTEES, PARTNERS, AND FRIENDS WHO CONTRIBUTED TO THE CONTENT OF THIS REPORT. © 2013 Arcus Foundation Front cover photo © Jurek Wajdowicz, Inside front cover photo © Isla Davidson Movements—whether social justice, animal conservation, or any other—take time and a sustained sense of urgency, In 2012 alone, we partnered with commitment, and fortitude. more than 110 courageous organizations hotos © Jurek Wajdowicz hotos © Jurek P working in over 40 countries around the globe. Dear Friends, Dear Friends, As I write this letter we are approaching the number 880, which represents a nearly 400 Looking back on some of the significant of the Congo. Continued habitat loss, spillover 50th anniversary of Dr. -

Pangolin-Id-Guide-Rast-English.Pdf

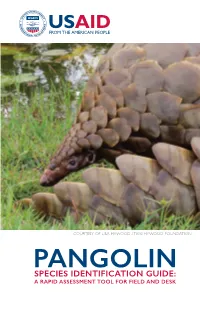

COURTESY OF LISA HYWOOD / TIKKI HYWOOD FOUNDATION PANGOLIN SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE: A RAPID ASSESSMENT TOOL FOR FIELD AND DESK Citation: Cota-Larson, R. 2017. Pangolin Species Identification Guide: A Rapid Assessment Tool for Field and Desk. Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development. Bangkok: USAID Wildlife Asia Activity. Available online at: http://www.usaidwildlifeasia.org/resources. Cover: Ground Pangolin (Smutsia temminckii). Photo: Lisa Hywood/Tikki Hywood Foundation For hard copies, please contact: USAID Wildlife Asia, 208 Wireless Road, Unit 406 Lumpini, Pathumwan, Bangkok 10330 Thailand Tel: +66 20155941-3, Email: [email protected] About USAID Wildlife Asia The USAID Wildlife Asia Activity works to address wildlife trafficking as a transnational crime. The project aims to reduce consumer demand for wildlife parts and products, strengthen law enforcement, enhance legal and political commitment, and support regional collaboration to reduce wildlife crime in Southeast Asia, particularly Cambodia; Laos; Thailand; Vietnam, and China. Species focus of USAID Wildlife Asia include elephant, rhinoceros, tiger, and pangolin. For more information, please visit www.usaidwildlifeasia.org Disclaimer The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. ANSAR KHAN / LIFE LINE FOR NATURE SOCIETY CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE 2 INTRODUCTION TO PANGOLINS 3 RANGE MAPS 4 SPECIES SUMMARIES 6 HEADS AND PROFILES 10 SCALE DISTRIBUTION 12 FEET 14 TAILS 16 SCALE SAMPLES 18 SKINS 22 PANGOLIN PRODUCTS 24 END NOTES 28 REGIONAL RESCUE CENTER CONTACT INFORMATION 29 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS TECHNICAL ADVISORS: Lisa Hywood (Tikki Hywood Foundation) and Quyen Vu (Education for Nature-Vietnam) COPY EDITORS: Andrew W. -

Ngos in the Global Conservation Movement

NGOs in the Global Conservation Movement: Can They Prevent Extinction? (African Apes as an Example) by Laura Prickett A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Approved April 2019 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: MaryJane Parmentier, Chair Gregg Zachary Leah Gerber ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2019 ABSTRACT Development throughout the course of history has traditionally resulted in the demise of biodiversity. As humans strive to develop their daily livelihoods, it is often at the expense of nearby wildlife and the environment. Conservation non- governmental organizations (NGOs), among other actors in the global agenda, have blossomed in the past century with the realization that there is an immediate need for conservation action. Unlike government agencies, conservation NGOs have an independent, potentially more objective outlook on procedures and policies that would benefit certain regions or certain species the most. They often have national and international government support, in addition to the credibility and influencing power to sway policy decisions and participate in international agendas. The key to their success lies in the ability to balance conservation efforts with socioeconomic development efforts. One cannot occur without the other, but they must work in coordination. This study looks at the example of African Great Apes. Eight ape- focused NGOs and three unique case studies will be examined in order to describe the impact that NGOs have. Most of these NGOs have been able to build the capacity from an initial conservation agenda, to incorporating socioeconomic factors that benefit the development of local communities in addition to the apes and habitat they set out to influence. -

Africa Security Brief a Publication of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies

NO. 28 / MAY 2014 AFRICA SECURITY BRIEF A PUBLICATION OF THE AFRICA CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES Wildlife Poaching: Africa’s Surging Trafficking Threat By Bradley anderson and Johan Jooste u Spikes in the prices of ivory and rhino horn have propelled an escalation in killings of African elephants and rhinoceroses. Without urgent corrective measures, extinction of these populations is likely. u This is not just a wildlife poaching problem but part of a global illicit trafficking network that is empowering violent groups and co-opting some elements of Africa’s security sector. u An immediate bolstering of Africa’s wildlife ranger network is needed to slow the pace of elephant and rhino killings and buy time. Addressing this threat over the longer term will require dramatically reducing the demand for these animal parts, especially within Asian markets. HIGHLIGHTS I condemn poaching and condemn those who entice young people to go hunting, because the game they kill is not for them…. It is at the behest of the powerful…. There is someone who makes a lot of money (from hunting), but those who die are often young people who innocently do it thinking that it makes life easy, it makes easy money, but they lose their lives. —Joaquim Chissano, former President of Mozambique and Founder of the Joaquim Chissano Foundation Wildlife Preservation Initiative in Mozambique A booming black market trade worth hundreds of significant net population declines have begun. Rhino millions of dollars is fueling corruption in Africa’s ports, poaching has also skyrocketed. Illegal killings in southern customs offices, and security forces as well as providing Africa from 2000 to 2007 were rare, frequently fewer than new revenues for insurgent groups and criminal networks 10 a year. -

Stolen Apes – the Illicit Trade in Chimpan- Zees, Gorillas, Bonobos and Orangutans

A RAPID RESPONSE ASSESSMENT STOLENTHE ILLICIT TRADE IN CHIMPANZEES, GORILLAS, BONOBOSAPES AND ORANGUTANS Stiles, D., Redmond, I., Cress, D., Nellemann, C., Formo, R.K. (eds). 2013. Stolen Apes – The Illicit Trade in Chimpan- zees, Gorillas, Bonobos and Orangutans. A Rapid Response Assessment. United Nations Environment Programme, GRID-Arendal. www.grida.no ISBN: 978-82-7701-111-0 Printed by Birkeland Trykkeri AS, Norway This publication was made possible through the financial UNEP and UNESCO support of the Government of Sweden. promote environmentally sound practices globally and in our own activi- Disclaimer ties. This publication is printed on fully recycled The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. The designations employed and the paper, FSC certified, post-consumer waste and presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on chlorine-free. Inks are vegetable-based and coatings the part of UNEP or contributory organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city, company or area or its authority, or concern- are water-based. Our distribution policy aims to ing the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. reduce our carbon footprint. STOLENTHE ILLICIT TRADE IN CHIMPANZEES, GORILLAS, BONOBOSAPES AND ORANGUTANS A RAPID RESPONSE ASSESSMENT Editorial Team Daniel Stiles Ian Redmond Doug Cress Christian Nellemann Rannveig Knutsdatter Formo Cartography Riccardo Pravettoni 4 PREFACE The trafficking of great apes adds additional and unwelcome pressures on charismatic fauna that provide an impetus for tourism and thus revenues to the economy. The illegal trade in wildlife makes up one part of the multi-billion dollar business that is environmental crime and is increasingly being perpetrated at the cost of the poor and vulnerable. -

USAID WA Bicc Scoping Study for Pangolin Conservation in West Africa

WEST AFRICA BIODIVERSITY AND CLIMATE CHANGE (WA BICC) SCOPING STUDY FOR PANGOLIN CONSERVATION IN WEST AFRICA December 2020 This document is made possible by the generous support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of its authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. This document was produced by the West Africa Biodiversity and Climate Change (WA BiCC) program through a Task Order under the Restoring the Environment through Prosperity, Livelihoods, and Conserving Ecosystems (REPLACE) Indefinite Quantity Contract (USAID Contract No. AID- OAA-I-13-00058, Order Number AID-624-TO-15-00002) between USAID and Tetra Tech, Inc. For more information on the WA BiCC program, contact: USAID/West Africa Biodiversity and Climate Change Tetra Tech 2nd Labone Link, North Labone Accra, Ghana Tel: +233 (0) 302 788 600 Email: www.tetratech.com/intdev Website: www.wabicc.org Stephen Kelleher Chief of Party Accra, Ghana Tel: +233 (0) 302 788 600 Vaneska Litz Project Manager Burlington, Vermont Tel: +1 802 495 0303 Email: [email protected] Citation: USAID/West Africa Biodiversity and Climate Change (WA BiCC). (2020). Scoping study for pangolin conservation in West Africa. 2nd Labone Link, North Labone, Accra, Ghana. 227pp. Cover Photo: Black-bellied Pangolin (Phataginus tetradactyla) being rehabilitated by the Sangha Pangolin Project, Dzangha-Sangha National Park, Central African Republic (Photo Credit: Alessandra Sikand and Sangha Pangolin Project) Author: Matthew H. Shirley, Orata Consulting, LLC Note: This report utilizes hyperlinks to outside studies, reports, articles, and websites. -

Ivory Markets in Central Africa

TRAFFIC IVORY MARKETS IN CENTRAL AFRICA REPORT Market Surveys in Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Gabon: 2007, 2009, 2014/2015 SEPTEMBER 2017 Sone NKOKE Christopher, Jean-François LAGROT, Stéphane RINGUET and Tom MILLIKEN TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Reprod uction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views of the authors expressed in this publication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. Published by TRAFFIC Central Africa Regional office Yaoundé, Cameroon and TRAFFIC International, Cambridge. Design by: Hallie Sacks © TRAFFIC 2017. Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. ISBN no: 978-1-85850-421-6 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722 Suggested citation: Nkoke, S.C. Lagrot J.F. Ringuet, S. and Milliken, T. (2017). Ivory Markets in Central Africa – Market Surveys in Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Gabon: 2007, 2009, 2014/2015. TRAFFIC. -

Elephant Meat Trade in Central Africa

Elephant Meat Trade in Central Africa Summary Report Daniel Stiles 2011 Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 45 About IUCN management. Membership is reviewed and reappointed IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, approximately every three years. helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. The group meets approximately every one to two years to review status and trends of elephant populations and to IUCN works on biodiversity, climate change, energy, discuss progress in specific areas related to conservation human livelihoods and greening the world economy by of the species. Since it was first convened in the mid supporting scientific research, managing field projects all 1970’s, the AfESG has considerably grown in size and over the world, and bringing governments, NGOs, the UN complexity. The AfESG Secretariat, based in Nairobi and companies together to develop policy, laws and best (Kenya), houses full-time staff to facilitate the work of the practice. group and to better serve the members’ needs. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental The challenge of the group is to find workable solutions organization, with more than 1,200 government and NGO to country and regional problems in an open-minded members and almost 11,000 volunteer experts in some atmosphere devoid of deliberate controversies. To meet 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by over 1,000 this challenge, the AfESG has provided technical expertise staff in 45 offices and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and advice by helping to facilitate the development of and private sectors around the world.Web: www.iucn.org national and sub-regional conservation strategies.The group has helped in the development of the Convention IUCN Species Survival Commission on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest system for monitoring the illegal killing of elephants of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global (MIKE). -

On the Trail N°29

On the Trail The defaunation bulletin n°29. Events from the 1st April to the 30th June, 2020 Quarterly information and analysis report on animal poaching and smuggling Published on March 22, 2021 Original version in French 1 On the Trail n°29. Robin des Bois Carried out by Robin des Bois (Robin Hood) with the support of the Brigitte Bardot Foundation, the Franz Weber Foundation and of the Ministry of Ecological and Solidarity Transition, France reconnue d’utilité publique 28, rue Vineuse - 75116 Paris Tél : 01 45 05 14 60 www.fondationbrigittebardot.fr Non Governmental Organization for the Protection of Man and the Environment Since 1985 14 rue de l’Atlas 75019 Paris, France tel : 33 (1) 48.04.09.36 - fax : 33 (1) 48.04.56.41 www.robindesbois.org [email protected] Publication Director : Charlotte Nithart Editors-in-Chief: Jacky Bonnemains and Charlotte Nithart Art Directors : Charlotte Nithart and Jacky Bonnemains Coordination : Elodie Crépeau-Pons Writing : Jacky Bonnemains, Gaëlle Guilissen, Jean-Pierre Edin, Charlotte Nithart and Elodie Crépeau-Pons. Research, Assistant Editor : Gaëlle Guilissen, Flavie Ioos, Elodie Crépeau-Pons and Irene Torres Márquez. Cartography : Dylan Blandel and Nathalie Versluys Cover : Giant humphead wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus) © Klaus Stiefel (CC BY-NC) English Translation : Robin des Bois Previous issues in English : http://www.robindesbois.org/en/a-la-trace-bulletin-dinformation-et-danalyses-sur-le-braconnage-et-la-contrebande/ Previous issues in French : http://www.robindesbois.org/a-la-trace-bulletin-dinformation-et-danalyses-sur-le-braconnage-et-la-contrebande/ On the Trail n°29. Robin des Bois 2 NOTE AND ADVICE TO READERS “On the Trail“, the defaunation magazine, aims to get out of the drip of daily news and to draw up every three months an organized and analyzed survey of poaching, smuggling and worldwide market of animal species protected by national laws and international conventions. -

Animal Protection and Sustainable Development: an Indivisible Relationship

Animal Protection and Sustainable Development: An indivisible relationship HLPF 2019 Animal People is a non-profit animal protection charity dedicated to raising public awareness of animal sentience and suffering, and to building connections among the animal welfare, rights, and conservation movements. The Animal Issues Thematic Cluster (AITC) is a coalition of animal protection and conservation organizations advocating for the care, protection, and conservation of animals and biodiversity within the United Nations Sustainable Development Agenda. Members of the AITC include: ACTAsia International Fund for Animal Welfare Animal People, Inc. (IFAW) African Network for Animal Welfare The Jeremy Coller Foundation Arc of Nubia Liberia Chimpanzee Rescue and Protection (LCRP) Arcus Foundation Nonviolence International Dr. Aysha Akhtar One More Generation Born Free The Orangutan Project Brighter Green Rapad Maroc The Brooke Reacción Climática Compassion in World Farming Safina Center Conservation X Labs S.P.A.R.E. Cruelty Free International Robyn Stark The Donkey Sanctuary Thinking Animals United Farm Animal Investment Risk & Return/Coller Capital (FAIRR) Vier Pfoten / FOUR PAWS German Speleological Federation A Well-Fed World Global Animal Law Welttierschutzgesellschaft Green Faith Wildlife Direct Innovation for the Development and the World Animal Net Protection of the Environment (IDEP) World Wildlife Web The International Action Network on Small Arms (IANSA) Animal Protection and Sustainable Development: An indivisible relationship Edited -

Ivory's Curse

Ivory’s Curse The Militarization & Professionalization of Poaching in Africa — by Varun Vira and Thomas Ewing April 2014 1 about c4ads about the authors C4ADS (www.c4ads.org) is a 501c3 non- Varun Vira received his Master’s degree in profit organization dedicated to data-driv- International Affairs from George Wash- en analysis and evidence-based reporting ington University and his Bachelor’s in of conflict and security issues worldwide. Economics and International Relation from We seek to alleviate the analytical burden Syracuse University. Varun has worked in carried by public sector institutions by ap- then-Senator Kerry’s office and at the Cen- plying manpower, depth, and rigor to ques- ter for Strategic and International Studies tions of conflict and security. Burke Chair in Strategy. Varun’s research at C4ADS focuses on South Asia and the Our approach leverages nontraditional in- Middle East. Varun has lived in India, Sin- vestigative techniques and emerging ana- gapore, the Netherlands and the UK, and lytical technologies. We recognize the value speaks Hindi and Urdu. of working on the ground in the field, cap- turing local knowledge, and collecting orig- Thomas Ewing received degrees in Russian, inal data to inform our analysis. At the same Political Science, and International Studies time, we employ cutting-edge technology from the University of Iowa, where he was to manage and analyze that data. The result inducted into the national Phi Beta Kappa is an innovative analytical approach to con- honor society. He is currently investigat- flict prevention and mitigation. ing illicit networks in Africa and Asia. -

Wildlife Poaching: Africa's Surging Trafficking Threat

NO. 28 / MAY 2014 AFRICA SECURITY BRIEF A PUBLICATION OF THE AFRICA CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES Wildlife Poaching: Africa’s Surging Trafficking Threat By Bradley anderson and Johan Jooste u Spikes in the prices of ivory and rhino horn have propelled an escalation in killings of African elephants and rhinoceroses. Without urgent corrective measures, extinction of these populations is likely. u This is not just a wildlife poaching problem but part of a global illicit trafficking network that is empowering violent groups and co-opting some elements of Africa’s security sector. u An immediate bolstering of Africa’s wildlife ranger network is needed to slow the pace of elephant and rhino killings and buy time. Addressing this threat over the longer term will require dramatically reducing the demand for these animal parts, especially within Asian markets. HIGHLIGHTS I condemn poaching and condemn those who entice young people to go hunting, because the game they kill is not for them…. It is at the behest of the powerful…. There is someone who makes a lot of money (from hunting), but those who die are often young people who innocently do it thinking that it makes life easy, it makes easy money, but they lose their lives. —Joaquim Chissano, former President of Mozambique and Founder of the Joaquim Chissano Foundation Wildlife Preservation Initiative in Mozambique A booming black market trade worth hundreds of significant net population declines have begun. Rhino millions of dollars is fueling corruption in Africa’s ports, poaching has also skyrocketed. Illegal killings in southern customs offices, and security forces as well as providing Africa from 2000 to 2007 were rare, frequently fewer than new revenues for insurgent groups and criminal networks 10 a year.