A Statistical Portrait of the Death Penalty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Death Row U.S.A

DEATH ROW U.S.A. Summer 2017 A quarterly report by the Criminal Justice Project of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Deborah Fins, Esq. Consultant to the Criminal Justice Project NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Death Row U.S.A. Summer 2017 (As of July 1, 2017) TOTAL NUMBER OF DEATH ROW INMATES KNOWN TO LDF: 2,817 Race of Defendant: White 1,196 (42.46%) Black 1,168 (41.46%) Latino/Latina 373 (13.24%) Native American 26 (0.92%) Asian 53 (1.88%) Unknown at this issue 1 (0.04%) Gender: Male 2,764 (98.12%) Female 53 (1.88%) JURISDICTIONS WITH CURRENT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 33 Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington, Wyoming, U.S. Government, U.S. Military. JURISDICTIONS WITHOUT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 20 Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico [see note below], New York, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin. [NOTE: New Mexico repealed the death penalty prospectively. The men already sentenced remain under sentence of death.] Death Row U.S.A. Page 1 In the United States Supreme Court Update to Spring 2017 Issue of Significant Criminal, Habeas, & Other Pending Cases for Cases to Be Decided in October Term 2016 or 2017 1. CASES RAISING CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS First Amendment Packingham v. North Carolina, No. 15-1194 (Use of websites by sex offender) (decision below 777 S.E.2d 738 (N.C. -

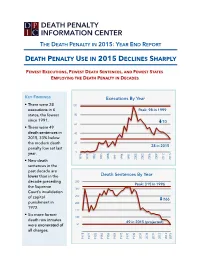

Year End Report

THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2015: YEAR END REPORT DEATH PENALTY USE IN 2015 DECLINES SHARPLY FEWEST EXECUTIONS, FEWEST DEATH SENTENCES, AND FEWEST STATES EMPLOYING THE DEATH PENALTY IN DECADES KEY FINDINGS Executions By Year • There were 28 100 executions in 6 Peak: 98 in 1999 states, the fewest 80 since 1991. ⬇70 60 • There were 49 death sentences in 40 2015, 33% below the modern death 20 28 in 2015 penalty low set last year. 0 • New death 1976 1979 1982 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 sentences in the past decade are lower than in the Death Sentences By Year decade preceding 350 Peak: 315 in 1996 the Supreme 300 Court’s invalidation of capital 250 ⬇266 punishment in 200 1972. 150 • Six more former 100 death row inmates 49 in 2015 (projected) were exonerated of 50 all charges. 1974 1977 1980 1983 1986 1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2015 THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2015: YEAR END REPORT U.S. DEATH PENALTY DECLINE ACCELERATES IN 2015 By all measures, use of and support for the death penalty Executions by continued its steady decline in the United States in 2015. The 2015 2014 State number of new death sentences imposed in the U.S. fell sharply from already historic lows, executions dropped to Texas 13 10 their lowest levels in 24 years, and public opinion polls revealed that a majority of Americans preferred life without Missouri 6 10 parole to the death penalty. Opposition to capital punishment polled higher than any time since 1972. -

Here Is a “Policy” Or “Custom” When There Was Significant Evidence of Brady Violations by the Orleans Parish District Attorney in This and Many Other Cases

No. _________ ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- EARL TRUVIA; GREGORY BRIGHT, Petitioners, v. HARRY F. CONNICK, in his capacity as District Attorney for the Parish of Orleans; GEORGE HEATH, Detective, Individually and in his official capacity as Officer of the City of New Orleans Police Department; JOSEPH MICELI, Individually and in his official capacity as Officer of the City of New Orleans Police Department; THE CITY OF NEW ORLEANS; EDDIE JORDAN, Respondents. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI --------------------------------- --------------------------------- ERWIN CHEMERINSKY PHILLIP E. FRIDUSS Counsel of Record LANDRUM, FRIDUSS UNIVERSITY OF & ASH, LLC CALIFORNIA, IRVINE 8681 Highway 92 SCHOOL OF LAW Suite 400 401 E. Peltason Woodstock, Georgia 30189 Irvine, California 92697-8000 (678) 384-3012 (949) 824-7722 [email protected] [email protected] ROBIN BRYAN CHEATHAM WILLIAM T. MITCHELL ADAMS & REESE, LLP MICHAEL HOFFER One Shell Square CRUSER & MITCHELL, LLP 701 Poydras St., Suite 4500 275 Scientific Dr. New Orleans, Louisiana 70139 Suite 2000 (504) 581-3234 Norcross, Georgia 30092 [email protected] (404) 881-2622 [email protected] [email protected] -

America's Fascination with Multiple Murder

CHAPTER ONE AMERICA’S FASCINATION WITH MULTIPLE MURDER he break of dawn on November 16, 1957, heralded the start of deer hunting T season in rural Waushara County, Wisconsin. The men of Plainfield went off with their hunting rifles and knives but without any clue of what Edward Gein would do that day. Gein was known to the 647 residents of Plainfield as a quiet man who kept to himself in his aging, dilapidated farmhouse. But when the men of the vil- lage returned from hunting that evening, they learned the awful truth about their 51-year-old neighbor and the atrocities that he had ritualized within the walls of his farmhouse. The first in a series of discoveries that would disrupt the usually tranquil town occurred when Frank Worden arrived at his hardware store after hunting all day. Frank’s mother, Bernice Worden, who had been minding the store, was missing and so was Frank’s truck. But there was a pool of blood on the floor and a trail of blood leading toward the place where the truck had been garaged. The investigation of Bernice’s disappearance and possible homicide led police to the farm of Ed Gein. Because the farm had no electricity, the investigators con- ducted a slow and ominous search with flashlights, methodically scanning the barn for clues. The sheriff’s light suddenly exposed a hanging figure, apparently Mrs. Worden. As Captain Schoephoerster later described in court: Mrs. Worden had been completely dressed out like a deer with her head cut off at the shoulders. -

Frequencies Between Serial Killer Typology And

FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS A dissertation presented to the faculty of ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY SANTA BARBARA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY in CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY By Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori March 2016 FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS This dissertation, by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: _______________________________ Ron Pilato, Psy.D. Chairperson _______________________________ Brett Kia-Keating, Ed.D. Second Faculty _______________________________ Maxann Shwartz, Ph.D. External Expert ii © Copyright by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, 2016 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS LERYN ROSE-DOGGETT MESSORI Antioch University Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA This study examined the association between serial killer typologies and previously proposed etiological factors within serial killer case histories. Stratified sampling based on race and gender was used to identify thirty-six serial killers for this study. The percentage of serial killers within each race and gender category included in the study was taken from current serial killer demographic statistics between 1950 and 2010. Detailed data -

Prosecutors' Perspective on California's Death Penalty

California District Attorneys Association Prosecutors' Perspective on California's Death Penalty Produced in collaboration with the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation MARCH 2003 GILBERT G. OTERO LAWRENCE G. BROWN President Executive Director Prosecutors' Perspective on California's Death Penalty MARCH 2003 CDAA BOARD OF DIRECTORS OFFICERS DIRECTORS PRESIDENT John Paul Bernardi, Los Angeles County Gilbert G. Otero Imperial County Cregor G. Datig, Riverside County SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT Bradford Fenocchio, Placer County David W. Paulson Solano County James P. Fox, San Mateo County SECRETARY-TREASURER Ed Jagels, Kern County Jan Scully Sacramento County Ernest J. LiCalsi, Madera County SERGEANT-AT-ARMS Martin T. Murray, San Mateo County Gerald Shea San Luis Obispo County Rolanda Pierre Dixon, Santa Clara County PAST PRESIDENT Frank J. Vanella, San Bernardino County Gordon Spencer Merced County Terry Wiley, Alameda County Acknowledgments The research and preparation of this document required the effort, skill, and collaboration of some of California’s most experienced capital-case prosecutors and talented administration- of-justice attorneys. Deep gratitude is extended to all who assisted. Special recognition is also deserved by CDAA’s Projects Editor, Kaye Bassett, Esq. This paper would not have been possible without the hard work and dedication of the California District Attorneys Association’s Death Penalty White Paper Ad Hoc Committee. CALIFORNIA DISTRICT ATTORNEYS ASSOCIATION DEATH PENALTY WHITE PAPER AD HOC COMMITTEE JIM ANDERSON ALAMEDA COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE TAMI R. BOGERT CALIFORNIA DISTRICT ATTORNEYS ASSOCIATION SUSAN BLAKE CRIMINAL JUSTICE LEGAL FOUNDATION LAWRENCE G. BROWN CALIFORNIA DISTRICT ATTORNEYS ASSOCIATION WARD A. CAMPBELL CALIFORNIA ATTORNEY GENERAL’S OFFICE BRENDA DALY SAN DIEGO COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE DANE GILLETTE CALIFORNIA ATTORNEY GENERAL’S OFFICE DAVID R. -

The Needle Lives to See Another Day! Three-Drug Protocol Ruled Constitutional in Glossip V. Gross

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 51 Number 3 Spring 2017 pp.881-890 Spring 2017 The Needle Lives to See Another Day! Three-Drug Protocol Ruled Constitutional in Glossip v. Gross Steven Paku Valparaiso University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven Paku, The Needle Lives to See Another Day! Three-Drug Protocol Ruled Constitutional in Glossip v. Gross, 51 Val. U. L. Rev. 881 (2017). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol51/iss3/10 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Paku: The Needle Lives to See Another Day! Three-Drug Protocol Ruled Co Comment THE NEEDLE LIVES TO SEE ANOTHER DAY! THREE-DRUG PROTOCOL RULED CONSTITUTIONAL IN GLOSSIP V. GROSS I. INTRODUCTION The Eighth Amendment provides one of the most important protections for citizens—prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment.1 Since the founding of the United States, the death penalty has been left to the states to implement, so long as it does not violate the Eighth Amendment.2 As a result, states have ratified their criminal codes and constitutions to keep their method of capital punishment within the constitutional limits.3 Challenges to states’ methods of execution began as early as the mid-1800s.4 In one such case from 2015, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in Glossip v. -

![APPROVAL SHEET This [Thesis] [Dissertation] [Case Study](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7014/approval-sheet-this-thesis-dissertation-case-study-927014.webp)

APPROVAL SHEET This [Thesis] [Dissertation] [Case Study

RUNNING HEAD: DETERMINING A CORRELATION BETWEEN CHILDHOOD TRAUMA & VIOLENT ACTS 1 APPROVAL SHEET This [thesis] [dissertation] [case study] [independent study] is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of [example degree designation: Master of Science] [Student Name] Approved: [Example date: March 15, 2019] Committee Chair / Advisor Committee Member 1 Committee Member 2 Committee Member 3 Outside FGCU Committee Member The final copy of this thesis [dissertation] has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. RUNNING HEAD: DETERMINING A CORRELATION BETWEEN CHILDHOOD TRAUMA & VIOLENT ACTS 2 Identifying Patterns Between the Sexual Serial Killer & Pedophile: Is There a Correlation Between their Violent Acts and Childhood Trauma? ______________________________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences Florida Gulf Coast University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Science _____________________________________________________________________________ By Alexis Droomer 2020 RUNNING HEAD: DETERMINING A CORRELATION BETWEEN CHILDHOOD TRAUMA & VIOLENT ACTS 3 Abstract Studies have been conducted to determine if a sexual serial killer and pedophile are similar and/or different to one another. Despite the difference in their criminal acts, sexual serial killers and pedophiles have similar characteristics. Biological, environmental and psychological theories of criminal behavior were studied which illustrated their significance to how a person can choose to commit a crime. The purpose of this study is to determine if there is a presence or absence within multiple forms of childhood trauma experienced between the sexual serial killer and pedophile. -

1372 Swimming Guide.Indd

• • • • • • • • • • • the huskers coaching staff season review athletic administration THIS IS NEBRASKA Table of Contents Nebraska Swimming & Diving 2010-11 Media Guide ThisIsNebraska ..............................1-21 Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................................1 Athletic Department Directory ...............................................................................................................................................2 Media Information and Services ...........................................................................................................................................3 This Is Nebraska ................................................................................................................................................................4-5 Sports Facilities .................................................................................................................................................................6-7 Husker Power ....................................................................................................................................................................8-9 Athletic Medicine and Nutrition ......................................................................................................................................10-11 -

Spring 2008 Rick Halperin, President Friends-- I Would Like to Thank Everyone Who Helped Make Our Recent Annual Conference Held in Houston on January 26 a Big Success

Seeking Justice IN TEXAS TEXASCOALITIONTOA BOLISHTHEDEATHPENALTY WORKINGTHROUGHEDUC ATIONANDACTION S P R I N G 2 0 0 8 2008 Off to a Great Start with More to Come! Inside This Issue: Music for Life in Beaumont, El Paso, and maybe Denton! From the Chair 2 The Sara Hickman concert series continues to roll through Texas cities with Mental Health Campaign 3 concerts in Corpus Christi, and Houston so far this year. Each concert has helped raise awareness of the death penalty, reached new audiences, and pro- Music for Life Tour 4 vided new contacts to help TCADP generate dialogue on the issue throughout the state. In March, Sara will be in Beaumont at Lamar University working with our Beaumont Chapter Updates 5, 6 chapter. El Paso Mayor John Cooke will sing and play guitar with Sara in El Paso at Club Member Spotlight 7 101. We want to be in Denton in May but are looking for a venue. (Let us know if you have a possible location.) Check page 4 for tour locations and dates. Spread the word Annual Award Winners 8 and come out for some great music with a message! TCADP Conference 9 At the Death House Door Panel Discussion and World Premier New Board Members 10 Don’t miss March 5 at the Texas Capitol, a panel discussion with clips from the movie. Ways You Can Help! 11 The panel discussion will include lots of great speakers. The film which features the Carlos Deluna case and the story of Rev. Carroll Mistaken Identity: Carlos Deluna Impending Executions Pickett will be debuting at the South by Southwest Film Festival (SXSW) on Sunday, March 9 at 4:00pm at The Paramount Impending Executions Theatre in Austin, TX. -

The Chair, the Needle, and the Damage Done: What the Electric Chair and the Rebirth of the Method-Of-Execution Challenge Could M

Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy Volume 15 Article 5 Issue 1 Fall 2005 The hC air, the Needle, and the Damage Done: What the Electric Chair and the Rebirth of the Method-of-Execution Challenge Could Mean for the Future of the Eighth Amendment Timothy S. Kearns Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cjlpp Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kearns, Timothy S. (2005) "The hC air, the Needle, and the Damage Done: What the Electric Chair and the Rebirth of the Method-of- Execution Challenge Could Mean for the Future of the Eighth Amendment," Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy: Vol. 15: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cjlpp/vol15/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHAIR, THE NEEDLE, AND THE DAMAGE DONE: WHAT THE ELECTRIC CHAIR AND THE REBIRTH OF THE METHOD-OF-EXECUTION CHALLENGE COULD MEAN FOR THE FUTURE OF THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT Timothy S. Kearnst INTRODUCTION ............................................. 197 I. THE ELECTROCUTION CASES ....................... 201 A. THE KEMMLER DECISION ............................ 201 B. THE KEMMLER EXECUTION ........................... 202 C. FROM IN RE KMMLER to "Evolving Standards" ..... 204 II. THE LOWER COURTS ................................ 206 A. THE CIRCUIT COURTS ................................. 206 B. THE STATE COURTS .................................. 211 C. NEBRASKA - THE LAST HOLDOUT .................. -

The Death Penalty in the OSCE Area: Background Paper 2013

This paper was prepared by the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR). Every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained in this paper is accurate and impartial. This paper updates The Death Penalty in the OSCE Area: Background Paper 2013. It is intended to provide a concise update to highlight changes in the status of the death penalty in OSCE participating States since the previous publication and to promote constructive discussion of this issue. It covers the period from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014. All comments or suggestions should be addressed to ODIHR’s Human Rights Department at [email protected]. Published by the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Miodowa 10 00-557 Warsaw Poland www.osce.org/odihr The© OSCE/ODIHR Death 2014 Penalty inISBN the ________ OSCE Area All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction is accompanied by an acknowledgement of ODIHR as the source. Designed by Nona Reuter Background Paper 2014 ODIHR This paper was prepared by the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR). Every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained in this paper is accurate and impartial. This paper updates The Death Penalty in the OSCE Area: Background Paper 2013. It is intended to provide a concise update to highlight changes in the status of the death penalty in OSCE participating States since the previous publication and to promote constructive discussion of this issue.