Chapter One: an Introduction………………………………………….Page 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 153 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 6, 2007 No. 22 House of Representatives The House met at 10:30 a.m. and was become true. It is Orwellian double- committee of initial referral has a called to order by the Speaker pro tem- think, an amazing concept. statement that the proposition con- pore (Mr. JOHNSON of Georgia). They believe that if you simply just tains no congressional earmarks. So f say you are lowering drug prices, poof, the chairman of the Appropriations it’s done, ignoring the reality that Committee, Mr. OBEY, conveniently DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO prices really won’t be lowered and submitted to the record on January 29 TEMPORE fewer drugs will be made available to that prior to the omnibus bill being The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- our seniors. considered, quote, ‘‘does not contain fore the House the following commu- They believe that if you just say you any congressional earmarks, limited nication from the Speaker: are implementing all of the 9/11 Com- tax benefits, or limited tariff benefits.’’ WASHINGTON, DC, mission’s recommendations, it changes But, in fact, Mr. Speaker, this omnibus February 6, 2007. the fact that the bill that was passed spending bill that the Democrats I hereby appoint the Honorable HENRY C. here on the floor doesn’t reflect the to- passed last week contained hundreds of ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, Jr. to act as Speaker pro tality of those recommendations. -

House Section

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JUNE 21, 2005 No. 83 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was I would like to read an e-mail that there has never been a worse time for called to order by the Speaker pro tem- one of my staffers received at the end Congress to be part of a campaign pore (Miss MCMORRIS). of last week from a friend of hers cur- against public broadcasting. We formed f rently serving in Iraq. The soldier says: the Public Broadcasting Caucus 5 years ‘‘I know there are growing doubts, ago here on Capitol Hill to help pro- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO questions and concerns by many re- mote the exchange of ideas sur- TEMPORE garding our presence here and how long rounding public broadcasting, to help The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- we should stay. For what it is worth, equip staff and Members of Congress to fore the House the following commu- the attachment hopefully tells you deal with the issues that surround that nication from the Speaker: why we are trying to make a positive important service. difference in this country’s future.’’ There are complexities in areas of le- WASHINGTON, DC, This is the attachment, Madam June 21, 2005. gitimate disagreement and technical I hereby appoint the Honorable CATHY Speaker, and a picture truly is worth matters, make no mistake about it, MCMORRIS to act as Speaker pro tempore on 1,000 words. -

Dear Peace and Justice Activist, July 22, 1997

Peace and Justice Awardees 1995-2006 1995 Mickey and Olivia Abelson They have worked tirelessly through Cambridge Sane Free and others organizations to promote peace on a global basis. They’re incredible! Olivia is a member of Cambridge Community Cable Television and brings programming for the local community. Rosalie Anders Long time member of Cambridge Peace Action and the National board of Women’s Action of New Dedication for (WAND). Committed to creating a better community locally as well as globally, Rosalie has nurtured a housing coop for more than 10 years and devoted loving energy to creating a sustainable Cambridge. Her commitment to peace issues begin with her neighborhood and extend to the international. Michael Bonislawski I hope that his study of labor history and workers’ struggles of the past will lead to some justice… He’s had a life- long experience as a member of labor unions… During his first years at GE, he unrelentingly held to his principles that all workers deserve a safe work place, respect, and decent wages. His dedication to the labor struggle, personally and academically has lasted a life time, and should be recognized for it. Steve Brion-Meisels As a national and State Board member (currently national co-chair) of Peace Action, Steven has devoted his extraordinary ability to lead, design strategies to advance programs using his mediation skills in helping solve problems… Within his neighborhood and for every school in the city, Steven has left his handiwork in the form of peaceable classrooms, middle school mediation programs, commitment to conflict resolution and the ripping effects of boundless caring. -

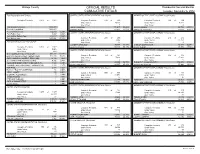

Official Results Cumulative Totals

Orange County OFFICIAL RESULTS Presidential General Election CUMULATIVE TOTALS Tuesday, November 6, 2012 Total Registration and Turnout UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 45th District MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 55th District Complete Precincts: 1,977 of 1,977 Complete Precincts: 519 of 519 Complete Precincts: 160 of 160 Under Votes: 19,555 Under Votes: 8,377 Over Votes: 7 Over Votes: 4 Total Registered Voters 1,683,001 JOHN CAMPBELL 171,417 58.46% CURT HAGMAN 56,736 65.39% Precinct Registration 1,683,001 SUKHEE KANG 121,814 41.54% GREGG D. FRITCHLE 30,033 34.61% Precinct Ballots Cast 552,018 32.80% UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 46th District MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 65th District Early Ballots Cast 5,343 0.32% Vote-by-Mail Ballots Cast 575,843 34.22% Total Ballots Cast 1,133,204 67.33% Complete Precincts: 290 of 290 Complete Precincts: 276 of 276 Under Votes: 7,682 Under Votes: 11,167 PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT Over Votes: 17 Over Votes: 8 LORETTA SANCHEZ 95,694 63.87% SHARON QUIRK-SILVA 68,988 52.04% Complete Precincts: 1,977 of 1,977 JERRY HAYDEN 54,121 36.13% CHRIS NORBY 63,576 47.96% Under Votes: 9,926 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 47th District MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 68th District Over Votes: 614 MITT ROMNEY PAUL RYAN (REP) 582,332 51.87% BARACK OBAMA JOSEPH BIDEN (DEM) 512,440 45.65% Complete Precincts: 184 of 184 Complete Precincts: 345 of 345 7,648 17,944 GARY JOHNSON JAMES P. GRAY (LIB) 14,132 1.26% Under Votes: Under Votes: 5 6 JILL STEIN CHERI HONKALA (GRN) 4,792 0.43% Over Votes: Over Votes: 49,599 54.72% 104,706 60.82% ROSEANNE BARR CINDY SHEEHAN (P-F) 3,348 0.30% GARY DELONG DONALD P. -

Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech

Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech David Supp-Montgomerie A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication Studies in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Christian Lundberg V. William Balthrop Carole Blair Lawrence Grossberg William Keith © 2013 David Supp-Montgomerie ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT David Supp-Montgomerie: Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech (Under the direction of Christian Lundberg) This dissertation is a critique of the idea that the artifice of public speech is a problem to be solved. This idea is shown to entail the privilege attributed to purportedly direct or unmediated speech in U.S. public culture. I propose that we attend to the ēthos producing effects of rhetorical concealment by asserting that all public speech is constituted through rhetorical artifice. Wherever an alternative to rhetoric is offered, one finds a rhetoric of non-rhetoric at work. A primary strategy in such rhetoric is the performance of sincerity. In this dissertation, I analyze the function of sincerity in contexts of public deliberation. I seek to show how claims to sincerity are strategic, demonstrate how claims that a speaker employs artifice have been employed to imply a lack of sincerity, and disabuse communication, rhetoric, and deliberative theory of the notion that sincere expression occurs without technology. In Chapter Two I begin with the original problem of artifice for rhetoric in classical Athens in the writings of Plato and Isocrates. -

The Calhoun-Liberty Journal

LIBERTY COUNTY 50¢ UNOFFICIAL THE CALHOUN-LIBERTY INCLUDES NOV. 6 GENERAL TAX ELECTION RESULTS PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT Romney, Ryan (REP) .........2298 OURNAL Obama, Biden (DEM) .........0939 CLJNews.comJ WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2012 Vol. 32, No. 44 Thomas Robert Stevens, Alden Link (OBJ) ...006 Gary Johnson, James P. Gray (LBT) .............009 Virgil H. Goode, Jr., James N. Clymer (CPF) .....003 Jill Stein, Cheri Honkala (GRE) .......................002 Finch elected Liberty County Sheriff; Andre Barnett, Kenneth Cross (REF) ..............000 Stewart Alexander, Alex Mendoza (SOC) ....002 Peta Lindsay, Yari Osori (PSL) ...................000 Roseanne Barr, Cindy Sheehan (PFP) .......016 Calhoun voters put Kimbrel in office Tom Hoefling, Jonathan D. Ellis (AIP) ..........002 Ross C. Anderson, Luis J. Rodriguez (JPF) ..001 There were some close races and anx- ious moments Tuesday night as big UNITED STATES SENATOR Connie Mack (REP).......................1536 changes were made in the sheriff’s of- Bill Nelson (DEM) ........................1584 fice on both sides of the Apalachicola Bill Gaylor (NPA) ............................069 River. Nick Finch, shown at left, was vot- Chris Borgia (NPA) ........................042 ed in as the new Liberty County Sheriff REP. IN CONGRESS after beating incumbent Donnie Conyers DISTRICT 2 by 177 votes. Calhoun County voted in Steve Southerland (REP) ...........2081 retired Blountstown Police Chief Glenn Al Lawson (DEM) ..........................1185 Kimbrel, right, as the new Sheriff. He STATE ATTORNEY -

2010-2019 Election Results-Moffat County 2010 Primary Total Reg

2010-2019 Election Results-Moffat County 2010 Primary Total Reg. Voters 2010 General Total Reg. Voters 2011 Coordinated Contest or Question Party Total Cast Votes Contest or Question Party Total Cast Votes Contest or Question US Senator 2730 US Senator 4681 Ken Buck Republican 1339 Ken Buck Republican 3080 Moffat County School District RE #1 Jane Norton Republican 907 Michael F Bennett Democrat 1104 JB Chapman Andrew Romanoff Democrat 131 Bob Kinsley Green 129 Michael F Bennett Democrat 187 Maclyn "Mac" Stringer Libertarian 79 Moffat County School District RE #3 Maclyn "Mac" Stringer Libertarian 1 Charley Miller Unaffiliated 62 Tony St John John Finger Libertarian 1 J Moromisato Unaffiliated 36 Debbie Belleville Representative to 112th US Congress-3 Jason Napolitano Ind Reform 75 Scott R Tipton Republican 1096 Write-in: Bruce E Lohmiller Green 0 Moffat County School District RE #5 Bob McConnell Republican 1043 Write-in: Michele M Newman Unaffiliated 0 Ken Wergin John Salazar Democrat 268 Write-in: Robert Rank Republican 0 Sherry St. Louis Governor Representative to 112th US Congress-3 Dan Maes Republican 1161 John Salazar Democrat 1228 Proposition 103 (statutory) Scott McInnis Republican 1123 Scott R Tipton Republican 3127 YES John Hickenlooper Democrat 265 Gregory Gilman Libertarian 129 NO Dan"Kilo" Sallis Libertarian 2 Jake Segrest Unaffiliated 100 Jaimes Brown Libertarian 0 Write-in: John W Hargis Sr Unaffiliated 0 Secretary of State Write-in: James Fritz Unaffiliated 0 Scott Gessler Republican 1779 Governor/ Lieutenant Governor Bernie Buescher Democrat 242 John Hickenlooper/Joseph Garcia Democrat 351 State Treasurer Dan Maes/Tambor Williams Republican 1393 J.J. -

GEORGE W. BUSH Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Halle Berry: a Biography Melissa Ewey Johnson Osama Bin Laden: a Biography Thomas R

GEORGE W. BUSH Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Halle Berry: A Biography Melissa Ewey Johnson Osama bin Laden: A Biography Thomas R. Mockaitis Tyra Banks: A Biography Carole Jacobs Jean-Michel Basquiat: A Biography Eric Fretz Howard Stern: A Biography Rich Mintzer Tiger Woods: A Biography, Second Edition Lawrence J. Londino Justin Timberlake: A Biography Kimberly Dillon Summers Walt Disney: A Biography Louise Krasniewicz Chief Joseph: A Biography Vanessa Gunther John Lennon: A Biography Jacqueline Edmondson Carrie Underwood: A Biography Vernell Hackett Christina Aguilera: A Biography Mary Anne Donovan Paul Newman: A Biography Marian Edelman Borden GEORGE W. BUSH A Biography Clarke Rountree GREENWOOD BIOGRAPHIES Copyright 2011 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rountree, Clarke, 1958– George W. Bush : a biography / Clarke Rountree. p. cm. — (Greenwood biographies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-38500-1 (hard copy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-313-38501-8 (ebook) 1. Bush, George W. (George Walker), 1946– 2. United States— Politics and government—2001–2009. 3. Presidents—United States— Biography. I. Title. E903.R68 2010 973.931092—dc22 [B] 2010032025 ISBN: 978-0-313-38500-1 EISBN: 978-0-313-38501-8 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. -

List of Candidate Filings

Contest/Candidate Proof List Consolidated General Election Contests: 1010 to 4945 - Contests On Ballot Candidates are in Random Alpha Order Candidates: Qualified Candidates Num Num Contest/District Vote For Cands Qualified Status Partisan PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT 1010 President, Vice President 0-0 Riverside County 1 6 6 ON BALLOT Incumbent(s): Barack Obama Elected Candidate(s): BARACK OBAMA, Democratic Qualified Date: 7/16/2012 JOSEPH BIDEN User Codes: Cand ID: 1 Filing Fee: $0.00 Fees Paid: $0.00 $0.00 Requirements Status ------------------------------------------------------- Sigs In Lieu Issued Sigs In Lieu Filed Declaration of Intent Issued Declaration of Intent Filed Candidate Statement Issued Candidate Statement Filed Declaration of Candidacy Issued Declaration of Candidacy Filed Code of Fair Campaign Practices Filed JILL STEIN, Green Qualified Date: 7/16/2012 CHERI HONKALA User Codes: Cand ID: 4 Filing Fee: $0.00 Fees Paid: $0.00 $0.00 Requirements Status ------------------------------------------------------- Sigs In Lieu Issued Sigs In Lieu Filed Declaration of Intent Issued Declaration of Intent Filed Candidate Statement Issued Candidate Statement Filed Declaration of Candidacy Issued Declaration of Candidacy Filed Code of Fair Campaign Practices Filed THOMAS HOEFLING, American Independent Qualified Date: 7/16/2012 ROBERT ORNELAS User Codes: Cand ID: 7 Filing Fee: $0.00 Fees Paid: $0.00 $0.00 Requirements Status ------------------------------------------------------- Sigs In Lieu Issued Sigs In Lieu Filed Declaration of -

Extensions of Remarks E1399 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

July 13, 2006 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1399 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS AMENDING PUBLIC HEALTH SERV- CONGRATULATING THE MENTAL members volunteer and maintain the expense ICE ACT WITH RESPECT TO NA- HEALTH CENTER OF CHAMPAIGN of the Hampshire County Library. In 1926, the TIONAL FOUNDATION FOR THE COUNTY ON ITS 50TH ANNIVER- auxiliary assisted the Legion in designing an CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL SARY honor roll plaque for the World War I service- AND PREVENTION men of Hampshire County. HON. TIMOTHY V. JOHNSON Post No. 137 has an active membership of OF ILLINOIS 400 in Capon Bridge, WV. Post Commander SPEECH OF Bob Brasher is assisted by President Sally IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Reid and Larry LaFollette, head of the Sons of HON. DANNY K. DAVIS Thursday, July 13, 2006 the Legion group. OF ILLINOIS Mr. JOHNSON of Illinois. Mr. Speaker, I rise Each of these organizations provides a today in honor of the Mental Health Center of venue for fellowship, volunteerism, and patriot- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Champaign County on the celebration of its ism. The service each member has given to Tuesday, July 11, 2006 50th anniversary. their Nation and community shall be forever The Champaign County Mental Health Clinic cherished and represented. Mr. DAVIS of Illinois. Mr. Speaker, Benjamin opened its doors 50 years ago as a program f Disraeli once exclaimed, ‘‘The health of the of the Champaign County Mental Health Soci- PENCE CALLS ON CONGRESS TO ety. On July 22, 1968, the Mental Health Cen- people is really the foundation upon which all STAND FOR THE SANCTITY OF ter became incorporated and changed its their happiness and all their powers as a state LIFE depend.’’ name to the Mental Health Center of Cham- paign County. -

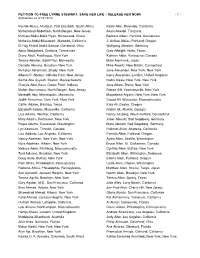

PETITION List 03-18-13 Columns

PETITION TO FREE LYNNE STEWART: SAVE HER LIFE – RELEASE HER NOW! • 1 • Signatories as of 03/18/13 Rashid Abass, Malabar, Port Elizabeth, South Africa Kevin Akin, Riverside, California Mohammad Abdelhadi, North Bergen, New Jersey Akula Akwabi, Tanzania Michael Abdul-Malik Ryan, Homewood, Illinois Barbara Albert, Hartford, Connecticut Mahasin Abdul-Musawwir, Alameda, California J. Ashlee Albies, Portland, Oregon El-Hajj Khalid Abdul-Samad, Cleveland, Ohio Wolfgang Albrecht, Germany Abou Abdulghani, Cordova, Tennessee Gale Albright, Hutto, Texas Diane Abell, Patchogue, New York Kathryn Alder, Vancouver, Canada Teresa Ableiter, Saint Paul, Minnesota Mark Aleshnick, Japan Danielle Abrams, Brooklyn, New York Mike Alewitz, New Britain, Connecticut Nicholas Abramson, Shady, New York Jane Alexander, New York, New York Alberto P. Abreus, Cliffside Park, New Jersey Kerry Alexander, London, United Kingdom Salma Abu Ayyash, Boston, Massachusetts Nadia Alexis, New York, New York Cheryle Abul-Husn, Crown Point, Indiana Jose Alfaro, Bronx, New York Maher Abunamous, North Bergen, New Jersey Robert Alft, Voorheesville, New York Meredith Aby, Minneapolis, Minnesota Magdalena Algarin, New York, New York Judith Ackerman, New York, New York Daoud Ali, Worcester, Massachusetts Caitlin Adams, Bastrop, Texas Kate Ali, Dexter, Oregon Elizabeth Adams, Marysville, California Nadim Ali, Atlanta, Georgia Lisa Adams, Weimar, California Nancy Alisberg, West Harftord, Connecticut Mary Adams, Rochester, New York Jaber Alkoufri, Bad Segeberg, Germany Roger Adams, Eastsound, -

Motherhood and Protest in the United States Since the Sixties

Motherhood and Protest in the United States Since the Sixties Georgina Denton Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History November 2014 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2014 The University of Leeds and Georgina Denton ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to take this opportunity to thank my supervisors Kate Dossett and Simon Hall, who have read copious amounts of my work (including, at times, chapter plans as long as the chapters themselves!) and have always been on hand to offer advice. Their guidance, patience, constructive criticism and good humour have been invaluable throughout this whole process, and I could not have asked for better supervisors. For their vital financial contributions to this project, I would like to acknowledge and thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the British Association for American Studies and the School of History at the University of Leeds. I am grateful to all the staff and faculty in the School of History who have assisted me over the course of my studies. Thanks must also go to my fellow postgraduate students, who have helped make my time at Leeds infinitely more enjoyable – including Say Burgin, Tom Davies, Ollie Godsmark, Nick Grant, Vincent Hiribarren, Henry Irving, Rachael Johnson, Jack Noe, Simone Pelizza, Juliette Reboul, Louise Seaward, Danielle Sprecher, Mark Walmsley, Ceara Weston, and Pete Whitewood.