Life of a Repentant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rough Guide to Naples & the Amalfi Coast

HEK=> =K?:;I J>;HEK=>=K?:;je CVeaZh i]Z6bVaÒ8dVhi D7FB;IJ>;7C7B<?9E7IJ 7ZcZkZcid BdcYgV\dcZ 8{ejV HVc<^dg\^d 8VhZgiV HVciÉ6\ViV YZaHVcc^d YZ^<di^ HVciVBVg^V 8{ejVKiZgZ 8VhiZaKdaijgcd 8VhVaY^ Eg^cX^eZ 6g^Zcod / AV\dY^EVig^V BVg^\a^Vcd 6kZaa^cd 9WfeZ_Y^_de CdaV 8jbV CVeaZh AV\dY^;jhVgd Edoojda^ BiKZhjk^jh BZgXVidHVcHZkZg^cd EgX^YV :gXdaVcd Fecf[__ >hX]^V EdbeZ^ >hX]^V IdggZ6ccjco^ViV 8VhiZaaVbbVgZY^HiVW^V 7Vnd[CVeaZh GVkZaad HdggZcid Edh^iVcd HVaZgcd 6bVa[^ 8{eg^ <ja[d[HVaZgcd 6cVX{eg^ 8{eg^ CVeaZh I]Z8Vbe^;aZ\gZ^ Hdji]d[CVeaZh I]Z6bVa[^8dVhi I]Z^haVcYh LN Cdgi]d[CVeaZh FW[ijkc About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections, and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The introductory colour section is designed to give you a feel for Naples and the Amalfi Coast, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The guide chapters cover the region in depth, each starting with a highlights panel, introduction and a map to help you plan your route. Contexts fills you in on history, books and film while individual colour sections introduce Neapolitan cuisine and performance. Language gives you an extensive menu reader and enough Italian to get by. 9 781843 537144 ISBN 978-1-84353-714-4 The book concludes with all the small print, including details of how to send in updates and corrections, and a comprehensive index. -

Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta, Soccavo, Pianura, Piscinola, Chiaiano, Scampia

Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 Assessorato allo Sviluppo Dipartimento Lavoro e Impresa Servizio Impresa e Sportello Unico per le Attività Produttive BANDO RETI Legge 266/97 - Annualità 2011 Agevolazioni a favore delle piccole imprese e microimprese operanti nei quartieri: Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta, Soccavo, Pianura, Piscinola, Chiaiano, Scampia, Miano, Secondigliano, San Pietro a Patierno, Ponticelli, Barra, San Giovanni a Teduccio, San Lorenzo, Vicaria, Poggioreale, Stella, San Carlo Arena, Mercato, Pendino, Avvocata, Montecalvario, S.Giuseppe, Porto. Art. 14 della legge 7 agosto 1997, n. 266. Decreto del ministro delle attività produttive 14 settembre 2004, n. 267. Pagina 1 di 12 Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 SOMMARIO ART. 1 – OBIETTIVI, AMBITO DI APPLICAZIONE E DOTAZIONE FINANZIARIA ART. 2 – REQUISITI DI ACCESSO. ART. 3 – INTERVENTI IMPRENDITORIALI AMMISSIBILI. ART. 4 – TIPOLOGIA E MISURA DEL FINANZIAMENTO ART. 5 – SPESE AMMISSIBILI ART. 6 – VARIAZIONI ALLE SPESE DI PROGETTO ART. 7 – PRESENTAZIONE DOMANDA DI AMMISSIONE ALLE AGEVOLAZIONI ART. 8 – PROCEDURE DI VALUTAZIONE E SELEZIONE ART. 9 – ATTO DI ADESIONE E OBBLIGO ART. 10 – REALIZZAZIONE DELL’INVESTIMENTO ART. 11 – EROGAZIONE DEL CONTRIBUTO ART. 12 –ISPEZIONI, CONTROLLI, ESCLUSIONIE REVOCHE DEI CONTRIBUTI ART. 13 – PROCEDIMENTO AMMINISTRATIVO ART. 14 – TUTELA DELLA PRIVACY ART. 15 – DISPOSIZIONI FINALI Pagina 2 di 12 Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 Art. 1 – Obiettivi, -

MUNICIPALITA' 4 S. Lorenzo, Vicaria, Poggioreale, Zona Industriale MUNICIPALITA' 7 Miano, Secondigliano, San Pietro a Patierno Servizio Attività Tecniche

Comune di Napoli Data: 25/05/2018, OD/2018/0000449 MUNICIPALITA' 4 S. Lorenzo, Vicaria, Poggioreale, Zona Industriale MUNICIPALITA' 7 Miano, Secondigliano, San Pietro a Patierno Servizio Attività Tecniche ORDINANZA DIRIGENZIALE N° 013 del 24/05/2018 OGGETTO: Istituzione di un dispositivo di traffico temporaneo di divieto di transito veicolare e di sosta con rimozione coatta in via Oreste Salomone, via Del Riposo, viale Fulco Ruffo di Calabria. IL DIRIGENTE Premesso che: • è in corso l'appalto dell’intervento di realizzazione della Stazione “Capodichino” della Linea 1 della Metropolitana di Napoli in capo al Servizio Realizzazione e Manutenzione Linea metropolitana 1; • la Società Concessionaria Metropolitana di Napoli S.p.A. ha evidenziato la necessità di predisporre i relativi provvedimenti di interdizione al traffico veicolare per consentire il rifacimento del manto bituminoso di alcuni tratti stradali in prossimità dell'accesso all'aeroporto di Napoli; • in data 11/05/2018 nel corso della della riunione della Conferenza dei Servizi, convocata con nota PG/2018/420736 del 09/05/2018, sono stati acquisiti i pareri rilasciati dal Servizio Realizzazione e Manutenzione Linea metropolitana 1, dal Servizio Autonomono Polizia Locale U.O. Aereoportuale, dal Servizio attività tecniche della Municipalità 7, dalla Società GE.S.A.C. S.p.A., della Società Autostrade per l’Italia S.p.A., della Società Metropolitana di Napoli S.p.A., della Società Capodichino AS.M. S.C.a.r.l.; • nella medesima riunione è stato stabilito ai fini viabilistici di procedere secondo le seguenti fasi, rappresentate nelle planimetrie che si allegano alla presente e in particolare; ◦ fase 1 con con decorrenza dal 28/05/2018 al 31/05/2018 dalle ore 23:00 alle ore 06:00 - in viale Fulco Ruffo di Calabria in direzione rotatoria, dalla confluenza con via Cupa Carbone all’intersezione con via Oreste Salomone, in via Oreste Salomone dal civico n. -

Metropolitane E Linee Regionali: Mappa Della

Formia Caserta Caserta Benevento Villa Literno San Marcellino Sant’Antimo Frattamaggiore Cancello Albanova Frignano Aversa Sant’Arpino Grumo Nevano 12 Acerra 11Aversa Centro Acerra Alfa Lancia 2 Aversa Ippodromo Giugliano Alfa Lancia 4 Casalnuovo igna Baiano Casoria 2 Melito 1 in costruzione Mugnano Afragola La P Talona e e co o linea 1 in costruzione Casalnuovo ont Ar erna iemont Piscinola ola P Brusciano Salice asalcist Scampia co P Prat C De Ruggier Chiaiano Par 1 11 Aeroporto Pomigliano d’ Giugliano Frullone Capodichino Volla Qualiano Colli Aminei Botteghelle Policlinico Poggioreale Materdei Madonnelle Rione Alto Centro Argine Direzionale Palasport Montedonzelli Salvator Stazione Rosa Cavour Centrale Medaglie d’Oro Villa Visconti Museo 1 Garibaldi Gianturco anni rocchia Quar v cio T esuvio Montesanto a V Quar La Piazza Olivella S.Gioeduc fficina cola to C Socca Corso Duomo T O onticelli onticelli De Meis er ollena O Quar P T T Quattro in costruzione a Barr P P C P Guindazzi fficina entr P ianura rencia raiano P C Vittorio Dante to isani ia Giornate Morghen Emanuele t v v o o o e Montesanto S.Maria Bartolo Longo Madonna dell’Arco Via del Pozzo 5 8 C Gianturco S.Giorgio Grotta Vanvitelli Fuga A Toledo S. Anastasia Università Porta 3 a Cremano del Sole Petraio Corso Vittorio Nolana S. Giorgio Cavalli di Bronzo Villa Augustea ostruzione Cimarosa Emanuele 3 12131415 Portici Bellavista Somma Vesuviana Licola B Palazzolo linea 7 in c Augusteo Municipio Immacolatella Portici Via Libertà Quarto Corso Vittorio Emanuele A Porto di Napoli Rione Trieste Ercolano Scavi Marina di Marano Corso Vittorio Ottaviano di Licola Emanuele Parco S.Giovanni Barra 2 Ercolano Miglio d’Oro Fuorigrotta Margherita ostruzione S. -

Il Vallone Dello Scudillo. Un Parco Agricolo E Boschivo Nel Cuore Di Napoli Da Salvare

IL VALLONE DELLO SCUDILLO. UN PARCO AGRICOLO E BOSCHIVO NEL CUORE DI NAPOLI DA SALVARE ALESSANDRA CAPUTI ANNA FAVA “A Napoli esiste un grande patrimonio di verde pubblico nel cuore della città. Nonostante i danni provocati dalla speculazione edilizia nel secondo dopoguerra, il verde urbano rappresenta ancora un decimo della superficie comunale. Aree agricole, boschi, parchi pubblici, colline ricoperte di macchia mediterranea e valloni, ricoprono il territorio a macchia di leopardo.” uesti luoghi, di straordinario valore di un grande polmone verde e una serie di passeggiate paesaggistico, storico e botanico, hanno panoramiche intorno alle colline del Vomero, di contribuito a rendere celebre il paesaggio Posillipo e di Capodimonte. Dopo la guerra, però, napoletano nel corso dei secoli. Fino il piano è falsificato in modo da rendere edificabili alla prima metà del Novecento, il centro le aree agricole. Il secondo piano, del 1972, mette Qstorico è stato circondato da una costellazione di in salvo il centro storico e alcune aree verdi ancora borghi e da una campagna fertilissima, che abbracciava inedificate. Il terzo, del 2004 e tuttora vigente, tutela a perdita d’occhio le colline circostanti e digradava fino in modo particolare il verde pubblico e prevede, per al mare. Durante il Fascismo, alcuni di questi borghi1 la prima volta, un “consumo di suolo zero”. Partendo furono annessi al Comune di Napoli, avviando il dal presupposto che «il complessivo sistema degli processo di urbanizzazione. All’indomani del conflitto spazi verdi costituisce con i centri storici il territorio bellico, la speculazione edilizia esplose, deturpando più pregiato della città»3, pianifica «un unico sistema per sempre il profilo armonioso delle colline. -

La Sfida Della Resilienza Urbana / La Sfida Della Resilienza Urban Resilience Rubriche/Sections

15 lala ss��dada delladella resilienzaresilienza urbanaurbana Vol. 8 n. 2 (DICEMBRE 2015) print ISSN 1974-6849, e-ISSN 2281-4574 TERRITORIO DELLA RICERCA Università degli Studi Federico II di Napoli SU INSEDIAMENTI E AMBIENTE Centro Interdipartimentale di Ricerca L.U.P.T. RIVISTA INTERNAZIONALE semestrale (Laboratorio di Urbanistica e Pianificazione Territoriale) DI CULTURA URBANISTICA “R. D’Ambrosio” http://www.tria.unina.it/index.php/tria Direttore scientifico /Editor-in-Chief Mario Coletta Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Condirettore / Coeditor-in-Chief Antonio Acierno Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Comitato scientifico /Scientific Committee Comitato centrale di redazione / Editorial Board Antonio Acierno (Caporedattore / Managing editor), Teresa Boccia, Robert-Max Antoni Seminaire Robert Auzelle Parigi (Francia) Angelo Mazza (Coord. relazioni internazionali / International rela- Rob Atkinson University of West England (Regno Unito) tions), Maria Cerreta, Antonella Cuccurullo, Candida Cuturi, Tuzin Baycan Levent Università Tecnica di Istambul (Turchia) Tiziana Coletta, Pasquale De Toro, Irene Ioffredo, Gianluca Roberto Busi Università degli Studi di Brescia (Italia) Lanzi, Emilio Luongo, Valeria Mauro, Ferdinando Musto, Sebastiano Cacciaguerra Università degli Studi di Udine (Italia) Raffaele Paciello, Francesca Pirozzi, Luigi Scarpa Clara Cardia Politecnico di Milano (Italia) Maurizio Carta Università degli Studi di Palermo (Italia) Redattori sedi periferiche / Territorial Editors Pietro Ciarlo Università -

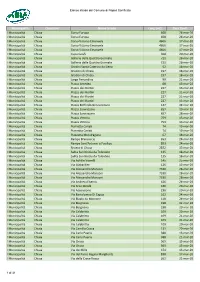

Municipalità Quartiere Nome Strada Lung.(Mt) Data Sanif

Elenco strade del Comune di Napoli Sanificate Municipalità Quartiere Nome Strada Lung.(mt) Data Sanif. I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Europa 608 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Europa 608 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Cupa Caiafa 368 20-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Galleria delle Quattro Giornate 721 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Galleria delle Quattro Giornate 721 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradini Santa Caterina da Siena 52 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradoni di Chiaia 197 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradoni di Chiaia 197 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Largo Ferrandina 99 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Amedeo 68 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Roffredo Beneventano 147 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 20-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Vittoria 759 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Vittoria 759 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Cariati 74 19-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Cariati 74 19-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Mondragone 67 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Rampe Brancaccio 653 24-mar-20 I Municipalità -

Del Comune Di Napoli

del comune di Napoli a cura del WWF Campania e della cooperativa La Locomotiva Centro di Documentazione CESPIA-CRIANZA Indagine sui servizi e la fruibilità dei Parchi e Giardini pubblici del comune di Napoli 3 Indice IL WWF A NAPOLI LA COOPERATIVA LA LOCOMOTIVA INTRODUZIONE E METODOLOGIA CARTA DEI PARCHI DEL COMUNE DI NAPOLI L’IMPORTANZA DELLE AREE VERDI E IL PROGRAMMA ECOREGIONALE DEL WWF DATI PRELIMINARI GLI INDICATORI UTILIZZATI CONCLUSIONI ALLEGATI: LE SCHEDE Municipalità no 1 Chiaia-S. Ferdiando-Posillipo Municipalità no 2 Avvocata-Mercato-Pendino-Porto-S. Giuseppe Municipalità no 3 Stella-S. Carlo all’Arena Municipalità no 4 S. Lorenzo-Vicaria-Poggioreale-Zona Industriale Municipalità no 5 Arenella-Vomero Municipalità no 6 Barra-S. Giovanni-Ponticelli Municipalità no 7 Miano-S. Pietro-Secondigliano Municipalità no 8 Chiaiano-Marianella-Piscinola-Scampia Municipalità no 9 Pianura-Soccavo Municipalità no 10 Bagnoli-Fuorigrotta ALLEGATI: APPROFONDIMENTI NATURALSITICI Bosco di Capodimonte Parco dei Camaldoli Parco del Poggio Parco Virgiliano Villa Comunale Villa Floridiana Parco Viviani RINGRAZIAMENTI E CREDITS Stesura e coordinamento gruppo di lavoro: Giovanni La Magna per il WWF, Anna Esposito per la cooperativa La Locomotiva. Hanno inoltre collaborato alla stesura del dossier: Giovanni La Magna, Ornella Capezzuto per il WWF, Anna Esposito, Marilina Cassetta per la cooperativa La Loco- motiva. Gli approfondimenti naturalistici sono stati curati da Anna Esposito e Giovanni La Magna, Nicola Bernardo, Giusy De Luca, Valerio Elefante, Martina Genovese, Natale Mirko, Antonio Pignalosa, Valerio Giovanni Russo, Andrea Sene- se, un gruppo di studenti di Scienze della Natura volontari del WWF. Gli approfondimenti del Real Parco di Capodi- monte, sono state fornite da Elio Esse. -

Naples Photo: Freeday/Shutterstock.Com Meet Naples, the City Where History and Culture Are Intertwined with Flavours and Exciting Activities

Naples Photo: Freeday/Shutterstock.com Meet Naples, the city where history and culture are intertwined with flavours and exciting activities. Explore the cemetery of skulls within the Fontanelle cemetery and the lost city of Pompeii, or visit the famous Vesuvius volcano and the island of Capri. Discover the lost tunnels of Naples and discover the other side of Naples, then end the day visiting the bars, restaurants and vivid nightlife in the evening. Castles, museums and churches add a finishing touch to the picturesque old-world feel. S-F/Shutterstock.com Top 5 Museum of Capodimonte The castle of Capodimonte boasts a wonderful view on the Bay of Naples. Buil... Castel Nuovo Also known as 'Maschio Angioino', this medieval castle dating back to 1279 w... Ovo Castle canadastock/Shutterstock.com Literally named 'Egg Castle', Castel dell'Ovo is a 12th-century fortress tha... Basilica of Saint Clare Not far from Church of Gesù Nuovo, the Basilica of Saint Clare is the bigges... Church of San Lorenzo Maggiore San Lorenzo Maggiore is an extraordinary building complex which mixes gothic... marcovarro/Shutterstock.com Updated 11 December 2019 Destination: Naples Publishing date: 2019-12-11 THE CITY is marked by contrasts and popular traditions, such as the annual miracle whereby San Gennaro’s ‘blood’ becomes liquid in front of the eyes of his followers. Naples is famous throughout the world primarly because of pizza (which, you'll discover, only constitutes a small part of the rich local cuisine) and popular music, with famous songs such as 'O Sole Mio'. canadastock/Shutterstock.com Museum of Capodimonte The historic city of Naples was founded about The castle of 3,000 years ago as Partenope by Greek Capodimonte boasts a merchants. -

Rete Metropolitana Napoli 1.Pdf

aversa piedimonte matese benevento caserta caserta formia frattamaggiore casoria cancello afragola acerra casalnuovo di napoli botteghelle volla poggioreale centro direzionale underground and railways map madonnelle argine palasport salvator gianturco rosa villa gianturco visconti formia vesuvio barra de meis duomo san ponticelli giovanni porta nolana san s. maria giovanni del pozzo bartolo longo licola quarto quarto torregaveta centro san pietrarsa giorgio cavalli di bronzo bellavista portici ercolano pompei castellammare sorrento pompei salerno pozzuoli capolinea autobus edenlandia bus terminal kennedy linea 1 ANM linea 2 Trenitalia collegamento marittimo torregaveta agnano line 1 line 2 sea transfer pozzuoli gerolomini linea 6 ANM parcheggio metrocampania nordest EAV parking line 6 metrocampania nordest line bagnoli ospedale cappuccini dazio funicolari ANM hospital funicolars linea circumvesuviana EAV circumvesuviana railway museo stazione museum station linea circumflegrea EAV castello stazione dell’arte circumflegrea railway castle art station linea cumana EAV università stazione in costruzione cumana railway university station under construction stadio scale mobili rete ferroviaria Trenitalia stadium escalators regional and national railway network mostra d’oltremare nodi di interscambio collegamento aeroporto interchange station airport transfer ostello internazionale Porto - Stazione Centrale - Aeroporto hostelling international APERTURA CHIUSURA PUOI ACQUISTARE I BIGLIETTI PRESSO I open closed DISTRIBUTORI AUTOMATICI O NEI RIVENDITORI -

Local Activities to Raise Awareness And

LOCAL ACTIVITIES TO RAISE AWARENESS AND PREPAREDNESS IN NEAPOLITAN AREA Edoardo Cosenza, Councillor for Civil Protection of Campania Region, Italy (better: professor of Structural Enngineering, University of Naples, Italy) Mineral and thermal water Port of Ischia (last eruption 1302) Campi Flegrei, Monte Nuovo, last eruption 1538 Mont Vesuvius, last eruption : march 23, 1944 US soldier and B25 air plan, Terzigno military base Municpalities and twin Regions 2 4 3 1 Evento del (Event of) 24/10/1910 Vittime (Fatalities) 229 Cetara 120, Maiori 50, Vietri sul Mare 50, Casamicciola Terme 9 Evento del (Event of) 25-28/03/1924 Vittime (Fatalities) 201 Amalfi 165, Praiano 36 Evento del (Event of) 25/10/1954 Vittime (Fatalities) 310 Salerno 109, Virtri sul Mare 100, Maiori 34, Cava de’ Tirreni 42, Tramonti 25, Evento del (Event of) 05/05/1998 Vittime (Fatalities) 200 Sarno area 184, Quindici 16 Analisi del dissesto da frana in campania. L.Monti, G.D’Elia e R.M.Toccaceli Atrani, September 2010 Cnr = National Council of Research From 1900: 51% of fatalities in Italy in the month of October !!! Cnr = National Council of Research From 1900: 25% of fatalities in Italy in Campania Region !!! Ipotesi nuova area rossa 2013 Municipi di Napoli Municipi di Napoli Inviluppo dei 1 - Chiaia,Posillipo, Inviluppo dei 1 - Chiaia,Posillipo, depositi degli ultimi S.Ferdinando depositi degli ultimi S.Ferdinando2 - Mercato, Pendino, 55 KaKa 2Avvocata, - Mercato, Montecalvario, Pendino, Avvocata,Porto, San Giuseppe.Montecalvario, Porto,3 - San San Giuseppe.Carlo all’Arena, 3Stella - San Carlo all’Arena, Stella4 - San Lorenzo, Vicaria, 4Poggioreale, - San Lorenzo, Z. -

Municipalità 1 - Chiaia, Posillipo, S

Indirizzi e contatti delle Municipalità cittadine Municipalità 1 - Chiaia, Posillipo, S. Ferdinando Sede Telefoni e fax Email Servizi Demografici Tel. 0817950512 [email protected] Chiaia - S.Ferdinando - Posillipo Fax 0817950502 [email protected] via S.Caterina a Chiaia, 76 [email protected] [email protected] Municipalità 2 - Avvocata, Montecalvario, Mercato, Pendino, Porto, S. Giuseppe Sede Telefoni e fax Email Ufficio anagrafe - Piazza Dante n. Fax 081 7950286 [email protected] 93 - 80135 Napoli (per i quartieri - 081 7950209 [email protected] Avvocata - Montecalvario - San Giuseppe - Porto) Municipalità 3 - Stella, S. Carlo all'Arena Sede Telefoni e fax Email Sezione San Carlo - Via Lieti, 97 Tel. 081 7952419 [email protected] 80131 Napoli Fax 081 7952451 municipalità[email protected] Sezione San Carlo - Via SS. Tel. 081 7952512 [email protected] Giovanni e Paolo, 125 Fax 081 7952501 municipalità[email protected] 80137 Napoli Sezione Stella - Via Sant'Agostino Tel. 081 7952632 [email protected] degli Scalzi, 61 80136 Napoli Fax 081 7952609 municipalità[email protected] Municipalità 4 - S. Lorenzo, Vicaria, Poggioreale, Zona Industriale Sede Telefoni e fax Email Ufficio Anagrafe di Poggioreale Tel. 081 7951317 [email protected] via E. Gianturco 99 - 80142 - Fax 081 7951378 [email protected] Napoli Ufficio Anagrafe di San Lorenzo Tel.081 7951918 [email protected] via Tribunali 227 - 80138 - Napoli Fax 081 7951934 [email protected] Municipalità 5 - Arenella, Vomero Sede Telefoni e fax Email Vomero Via Raffaele Morghen n.