Interview with James Thompson # IST-A-L-2013-054.15 Interview # 15: March 30, 2015 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illinois Assembly on Political Representation and Alternative Electoral Systems I 3 4 FOREWORD

ILLINOIS ASSEMBLY ON POLITICAL REPRESENTATION AND ALTERNATIVE # ELECTORAL SYSTEMS FINAL REPORT AND BACKGROUND PAPERS ILLINOIS ASSEMBLY ON POLITICAL REPRESENTATION AND ALTERNATIVE #ELECTORAL SYSTEMS FINAL REPORT AND BACKGROUND PAPERS S P R I N G 2 0 0 1 2 CONTENTS Foreword...................................................................................................................................... 5 Jack H. Knott I. Introduction and Summary of the Assembly Report ......................................................... 7 II. National and International Context ..................................................................................... 15 An Overview of the Core Issues ....................................................................................... 15 James H. Kuklinski Electoral Reform in the UK: Alive in ‘95.......................................................................... 17 Mary Georghiou Electoral Reform in Japan .................................................................................................. 19 Thomas Lundberg 1994 Elections in Italy .........................................................................................................21 Richard Katz New Zealand’s Method for Representing Minorities .................................................... 26 Jack H. Nagel Voting in the Major Democracies...................................................................................... 30 Center for Voting and Democracy The Preference Vote and Election of Women ................................................................. -

Chapter 2, State Executive Branch

CHAPTER TWO STATE EXECUTIVE BRANCH The Council of State Governments 23 THE GOVERNORS, 1986-87 By Thad L. Beyle Considerable interest in gubernatorial elec Rhode lsland), and Madeleine Kunin (D.Ver. tions was expressed during 1986-87, a period mont). between presidential campaign& Fint, there Thirteen incumbent governors were constitu was considerable political activity in the form tionally ineligible to seek another term: Bob of campaigning as 39 governol"8hips were con Graham (D.Florida), George Ariyoshi (D·Ha· tested. Second, as the problema 8B8OCiated with waii), John Carlin (D.Kansas), Martha Layne the federal deficit and the ideoiogicalstance of Collins (D.Kentucky), Joseph Brennan (D the Reagan administration continued, gover Maine), Harry Hughes (D.Maryland), Thney non and other state leaders made difficult deci Anaya (D.New Mexico), George Nigh CD·Okla sions on the extent of their statal' commitment homa), Victor Atiyeh (R.Oregon), Dick Thorn· to a range ofpolicy concerns. Third was the con burgh (R.Pennsylvania), Richard Riley (D. tinuing role of the governorship in producing South Carolina), William Janklow (R.South serious presidential candidates aft.er a period Dakota), and Lamar Alexander (R.Thnne68e6). in which it was believed that governors could Seven incumbents opted to retire; George no longer be considered as potential candidates Wallace (D.Alabama), Bruce Babbitt CD-Arizo for president.) Fourth was the negative publi. na), Richard Lamm (D-Colorado), John Evans city fostered by the questionable actions of (D.Idaho). William Allain (D-Mississippi), several governors. which in one case lead to an Robert Kerry CD·Nebraska), and Ed Hershler impeachment and in two others contributed to CD ·Wyoming). -

Fiscal Year 2005

THE CENTER FOR STATE POLICY AND LEADERSHIP 2005 ANNUAL REPORT UNIVERSITY of ILLINOIS at SPRINGFIELD THE CENTER FOR STATE POLICY AND LEADERSHIP Our Mission he UIS Center for State Policy and Leadership, T located in the Illinois state capital, emphasizes policy and state governance. The Center identifies and addresses public policy issues at all levels of government, promotes governmental effectiveness, fosters leadership development, engages in citizen education, and contributes to the dialogue on matters of significant public concern. Working in partnership with government, local communities, citizens, and the nonprofit sector, the Center contributes to the core missions of the University of Illinois at Springfield by mobilizing the expertise of its faculty, staff, students, and media units to carry out research and dissemination, professional development and training, civic engagement, technical assistance, and public service activities. Our Vision he UIS Center for State Policy and Leadership T will be an independent and nationally recognized resource for scholars and Illinois policy-makers, opinion leaders, and citizens. The Center will be known for its high-quality, nonpartisan public policy research, innovative leadership and training programs, and timely and thought-provoking educational forums, publications, media productions, and public radio broadcasts. The Center will take an active role in the development of ethical, competent, and engaged students, faculty, staff, and community and government leaders by providing intern, civic engagement, and professional development opportunities, in-person and through the use of multi-media and on-line technologies. Produced by Center Publications/Illinois Issues. Peggy Boyer Long, director; Amy Karhliker, editor; Diana L.C. Nelson, art director. The University of Illinois at Springfield is an affirmative action/equal opportunity institution. -

Robert D. Ray

ROBERT D. RAY Few names in Iowa’s 172-year history are as instantly recognizable as Robert D. Ray. He was born in Des Moines September 26, 1928 and passed away in Des Moines on July 8, 2018. In the intervening years, Robert D. Ray’s leadership touched the lives of generations of Iowans on dozens of fronts and reached global impact on several occasions. Ray grew up in the Drake neighborhood and met the love of his life and future wife, Billie Lee Hornberger, at what is now First Christian Church while they were students at Roosevelt High School. The Roosevelt High School sweethearts started dating in 1945 and were married on December 22, 1951. His life revolved around love of family, first as a son and brother, followed by his passion to be a devoted husband, dedicated father to the Ray’s three daughters and adoring grandfather to their eight grandchildren. After World War II, Ray served the U. S. Army in Japan. He graduated from Drake University with a business degree in 1952 and law degree 1954. He was a law and reading clerk in the Iowa State Senate, where he began to understand government and relish politics. Later, he built a successful practice as a trial lawyer with two brothers named Lawyer; the firm was Lawyer, Lawyer and Ray. In 1963, Ray was elected Iowa Republican State Chairman and became a member of the Republican National Committee. After heavy losses in the 1964 Goldwater debacle, Ray resolved to rebuild and the GOP elected three new Congressmen and 88 state legislators in 1966. -

Interview with Dawn Clark Netsch # ISL-A-L-2010-013.07 Interview # 7: September 17, 2010 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Dawn Clark Netsch # ISL-A-L-2010-013.07 Interview # 7: September 17, 2010 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 Note to the Reader: Readers of the oral history memoir should bear in mind that this is a transcript of the spoken word, and that the interviewer, interviewee and editor sought to preserve the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein. We leave these for the reader to judge. DePue: Today is Friday, September 17, 2010 in the afternoon. I’m sitting in an office located in the library at Northwestern University Law School with Senator Dawn Clark Netsch. Good afternoon, Senator. Netsch: Good afternoon. (laughs) DePue: You’ve had a busy day already, haven’t you? Netsch: Wow, yes. (laughs) And there’s more to come. DePue: Why don’t you tell us quickly what you just came from? Netsch: It was not a debate, but it was a forum for the two lieutenant governor candidates sponsored by the group that represents or brings together the association for the people who are in the public relations business. -

Boyd Rice Is a Putz in My Book, but Examining His Politics, You'll Find a More Compelling and Compelled Point of View Than Many Other Cultural Commentators

Regarding Evil by Ross B. Cisneros B.F.A The Cooper Union School of Art, 2002 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN VISUAL STUDIES AT THE_____ __ ATMTSSACHUSETTS INSTRTUT MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOG OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2005 JUN 28 2005 c 2005 Ross B. Cisneros, All rights reserved. LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic ROTCH copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Degrtmei't Aehitecture '-M~y 6, 2005 Certified by: Krzy'sztof Wodiczko Professor of Visual Arts Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Ad6le Naud6 Santos Chair, Committee on Graduate Students Acting Head, Department of Architecture Dean, School of Architecture and Planning 2 REGARDING EVIL By ROSS B. CISNEROS Submitted to the Department of Architecture On May 6, 2005 in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Visual Studies ABSTRACT The transnational summit, Regarding Evil, was called to assembly with the simultaneous sounding of the trumps in six sites around the world, projected simulcast. In collaboration with the six individuals who were issued the instruments, each announced their particular state of emergency and converged at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with a seventh blast. Scotsman Kenneth Smith assumed the role of 7th piper. Artists and scholars of international reputation had been invited to present visual and discursive material confronting the elusive and immeasurable subject of Evil, its transpolitical behaviors, charismatic aesthetic, and viral disbursement in the vast enterprise of simulation, symbolic power, and catastrophe. -

Legislative Oversight in Illinois

Legislative Oversight in Illinois Capacity and Usage Assessment Oversight through Analytic Bureaucracies: Moderate Oversight through the Appropriations Process: Moderate Oversight through Committees: Moderate Oversight through Administrative Rule Review: High Oversight through Advice and Consent: Moderate Oversight through Monitoring Contracts: Limited Judgment of Overall Institutional Capacity for Oversight: High Judgment of Overall Use of Institutional Capacity for Oversight: High Summary Assessment Illinois’ legislature appears to do an adequate job of overseeing the executive, despite having substantial institutional capacity to produce information and institutional structures that facilitate bipartisan participation. We note that the absence of recordings of oversight hearings and other committee hearings makes it very difficult to assess legislators’ performance on oversight. The appropriations process appears to be controlled by legislative leadership. And there is a contest of wills between the executive branch and the legislature that led to a two year budget stalemate. Major Strengths Illinois balances partisan membership on its oversight committee, the Legislature Audit Committee (LAC) and its Joint Committee on Administrative Rules (JCAR), which insures that the minority party has a voice in these hearings. The legislature’s rule review powers are extraordinarily strong—trending toward a legislative veto. Furthermore, the state’s legislature does appear to make substantial use of audit reports in creating legislation and during the budget and appropriations process. Joint committee meetings make it easier to communicate audit reports to both chambers. The appropriations process is often contentious, however, and appears to be infused with partisan politics. The Illinois General Assembly seems to scrutinize appointees thoroughly, and it intervenes in the governor’s efforts to reorganize agencies. -

Six Rivers, Five Glaciers, and an Outburst Flood: the Considerable Legacy of the Illinois River

SIX RIVERS, FIVE GLACIERS, AND AN OUTBURST FLOOD: THE CONSIDERABLE LEGACY OF THE ILLINOIS RIVER Don McKay, Chief Scientist, Illinois State Geological Survey 615 East Peabody Drive, Champaign, Illinois 61820 [email protected] INTRODUCTION The waters of the modern Illinois River flow gently through looping meanders bordered by quiet backwater lakes and drop only a few inches in each river mile. Concealed beneath this gentle river is geologic evidence that the Illinois descended from ancient rivers with surprising and sometimes violent histories. The geologic story of the Illinois River is not only an account of an interesting chapter of Earth history, but it also reveals a rich geologic legacy of valuable and vulnerable resources that should be managed and used wisely. Modern, detailed, geologic field mapping has enabled new insights into the river’s history. Begun in 2000 by the Illinois State Geological Survey (ISGS), geologic mapping in the Middle Illinois River Valley area (Fig 1) was undertaken to aid planning for an expansion of Illinois Highway 29 between Chillicothe and I-180 west of Hennepin. Mapping was focused initially on the western bluff and valley bottom west of the river near the present highway but has since been expanded to more than 275 sq mi in Putnam, Marshall, and Peoria counties. Funding was provided by Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) and by ISGS. Several maps are scheduled to be published (McKay and others 2008a, 2008b, 2008c). Figure 1. Location of recent and ongoing geologic mapping area in the Middle Illinois River Valley region of north-central Illinois (left) and northeastern portion of the Chillicothe 7.5-minute surficial geology map (right) showing areas of river deposits, glacial tills, and bedrock where they occur at land surface. -

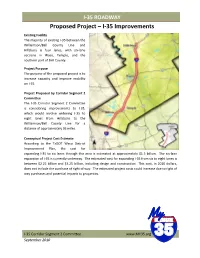

Proposed Project – I-35 Improvements

I‐35 ROADWAY Proposed Project – I‐35 Improvements Existing Facility The majority of existing I‐35 between the Williamson/Bell County Line and Hillsboro is four lanes, with six‐lane sections in Waco, Temple, and the southern part of Bell County. Project Purpose The purpose of the proposed project is to increase capacity and improve mobility on I‐35. Project Proposed by Corridor Segment 2 Committee The I‐35 Corridor Segment 2 Committee is considering improvements to I‐35, which would involve widening I‐35 to eight lanes from Hillsboro to the Williamso n/Bell County Line for a distance of approximately 93 miles. Conceptual Project Cost Estimate According to the TxDOT Waco District Improvement Plan, the cost for expanding I‐35 to six lanes through this area is estimated at approximately $1.5 billion. The six‐lane expansion of I‐35 is currently underway. The estimated cost for expanding I‐35 from six to eight lanes is between $2.25 billion and $3.25 billion, including design and construction. This cost, in 2010 dollars, does not include the purchase of right of way. The estimated project costs could increase due to right of way purchases and potential impacts to properties. I‐35 Corridor Segment 2 Committee www.MY35.org September 2010 I‐35 ROADWAY Proposed Project – I‐35E from I‐20 to Hillsboro Existing Facility The existing I‐35E facility is four lanes from Hillsboro to approximately ten miles south of I‐20, where it transitions to six and then eight lanes. Project Purpose The purpose of the proposed project is to increase capacity and improve overall mobility on I‐35E. -

Greater OKLAHOMA CITY at a Glance

Greater OKLAHOMA CITY at a glance 123 Park Avenue | Oklahoma City, OK 73102 | 405.297.8900 | www.greateroklahomacity.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Location ................................................4 Economy .............................................14 Tax Rates .............................................24 Climate ..................................................7 Education ...........................................17 Utilities ................................................25 Population............................................8 Income ................................................21 Incentives ...........................................26 Transportation ..................................10 Labor Analysis ...................................22 Available Services ............................30 Housing ...............................................13 Commercial Real Estate .................23 Ranked No. 1 for Best Large Cities to Start a Business. -WalletHub 2 GREATER OKLAHOMA CITY: One of the fastest-growing cities is integral to our success. Our in America and among the top ten low costs, diverse economy and places for fastest median wage business-friendly environment growth, job creation and to start a have kept the economic doldrums business. A top two small business at bay, and provided value, ranking. One of the most popular stability and profitability to our places for millennials and one of companies – and now we’re the top 10 cities for young adults. poised to do even more. The list of reasons you should Let us introduce -

Pre-Disaster Mitigation Floodwall Projects Cities of Marseilles, Ottawa, and Peru, Lasalle County, Illinois Village of Depue, Bureau County, Illinois January 2018

Final Programmatic Environmental Assessment Pre-Disaster Mitigation Floodwall Projects Cities of Marseilles, Ottawa, and Peru, LaSalle County, Illinois Village of DePue, Bureau County, Illinois January 2018 Prepared by Booz Allen Hamilton 8283 Greensboro Drive McLean, VA 22102 Prepared for FEMA Region V 536 South Clark Street, Sixth Floor Chicago, IL 60605 Photo attributes: Top left: City of Ottawa Top right: City of Peru Bottom left: City of Marseilles Bottom right: Village of DePue Pre-Disaster Mitigation Floodwall Projects Page ii January 2018 Programmatic Environmental Assessment Acronyms and Abbreviations List of Acronyms and Abbreviations oC Degrees Celsius ACHP Advisory Council on Historic Preservation AD Anno Domini AIRFA American Indian Religious Freedom Act APE Area of Potential Effect ARPA Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 BFE Base Flood Elevation BLM Bureau of Land Management BMP Best Management Practice BP Before Present CAA Clean Air Act CEQ Council on Environmental Quality C.F.R. Code of Federal Regulations CLOMR Conditional Letter of Map Revision CRS Community Rating System CWA Clean Water Act CWS Community Water Supplies dB decibels EA Environmental Assessment EO Executive Order EPA Environmental Protection Agency ESA Endangered Species Act FEMA Federal Emergency Management Agency FIRM Flood Insurance Rate Map Pre-Disaster Mitigation Floodwall Projects Page iii January 2018 Programmatic Environmental Assessment Acronyms and Abbreviations FONSI Finding of No Significant Impact FPPA Farmland Protection Policy -

Pets Are Popular with U.S. Presidents

Pets Are Popular With U.S. Presidents Most people have heard by now that President-elect Barack Obama promised his two daughters a puppy if he were elected president. Obama called choosing a dog a “major issue” for the new first family. It seems that pets have always been very popular with U.S. presidents. Only two of the 44 presidents -- Chester A. Arthur and Franklin Pierce -- left no record of having pets. Many presidents and their children had dogs and cats in the White House. President and Mrs. Bush have two dogs and a cat living with them -- the dogs are named Barney and Miss Beazley and the cat is India. But there have been many unusual presidential pets as well. President Calvin Coolidge may have had the most pets. NEWS WORD BOX He had a pygmy hippopotamus, six dogs, a bobcat, a goose, a donkey, a cat, two lion cubs, an antelope, and popular issue record wallaby a wallaby. President Herbert Hoover had several dogs pygmy hippopotamus and his son had two pet alligators, which sometimes took walks outside the White House. Caroline Kennedy, the daughter of President John F. Kennedy, had a pony named Macaroni. She would ride Macaroni around the White House grounds. Some pets also worked while at the White House. Pauline the cow was the last cow to live at the White House. She provided milk for President William Taft. To save money during World War I, President Woodrow Wilson brought in a flock of sheep to trim the White House lawn. The flock included a ram named Old Ike.