Correspondent Visions of Vietnam by Mark A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Framing 'The Other'. a Critical Review of Vietnam War Movies and Their Representation of Asians and Vietnamese.*

Framing ‘the Other’. A critical review of Vietnam war movies and their representation of Asians and Vietnamese.* John Kleinen W e W ere Soldiers (2002), depicting the first major clash between regular North-Vietnamese troops and U.S. troops at Ia Drang in Southern Vietnam over three days in November 1965, is the Vietnam War version of Saving Private Ryan and The Thin Red Line. Director, writer and producer, Randall Wallace, shows the viewer both American family values and dying soldiers. The movie is based on the book W e were soldiers once ... and young by the U.S. commander in the battle, retired Lieutenant General Harold G. Moore (a John Wayne- like performance by Mel Gibson).1 In the film, the U.S. troops have little idea of what they face, are overrun and suffer heavy casualties. The American GIs are seen fighting for their comrades, not their fatherland. This narrow patriotism is accompanied by a new theme: the respect for the victims ‘on the other side’. For the first time in the Hollywood tradition, we see fading shots of dying ‘VC’ and of their widows reading loved ones’ diaries. This is not because the filmmaker was emphasizing ‘love’ or ‘peace’ instead of ‘war’, but more importantly, Wallace seems to say, that war is noble. Ironically, the popular Vietnamese actor, Don Duong, who plays the communist commander Nguyen Huu An who led the Vietnamese People’s Army to victory, has been criticized at home for tarnishing the image of Vietnamese soldiers. Don Duong has appeared in several foreign films and numerous Vietnamese-made movies about the War. -

Top 30 Vietnam War Books

America's wars have inspired some of the world's best literature, and the Vietnam War is no exception By Marc Leepson The Vietnam War has left many legacies. Among the most positive is an abundance of top-notch books, many written by veterans of the conflict. NONFICTION These include winners of National Book Awards and Pulitzer Prizes, AMERICA'S LONGEST WAR: • • • • • both fiction and nonfiction. A slew of war memoirs stand with the best THE UNITED STATES writing of that genre. Nearly all of the big books about the Vietnam War AND VIETNAM, 1950-1975 remain in print in 2014, and the 50th anniversary commemoration of by George Herring, 1978 the war is an opportune time to recognize the best of them. This book is widely viewed as the besj concise history of the Vietnam War. Her• In the short history of Vietnam War literature, publishers would ring, a former University of Kentucky hardly touch a book on the war until the late 1970s and early 1980s—a history professor, covers virtually every part of the self-induced national amnesia about that conflict and its important event in the conflict, present• outcome. After sufficient time had elapsed to ease some of the war's ing the war objectively and assessing its psychic wounds, we saw a mini explosion of important books. Most legacy. Revised and updated over the of the books on the following, very subjective, list of the top 15 fiction years, America's Longest War is used in and nonfiction titles, came out in the late '70s and throughout the '80s. -

I Am Getting Over a Virus That I May First Have Noticed in June, When the Secretary at the Tech Firm I Manage Pointed out That I Wasn't Making Sense

I am getting over a virus. By Dan Duffy. Address: [email protected]. Distributed January 2008. I am getting over a virus that I may first have noticed in June, when the secretary at the tech firm I manage pointed out that I wasn't making sense. Making sense is my job, sending lawyers and engineers out to evaluate the intellectual property in software developed with open source components, and making sure that what they come back with adds up. If I had to explain why I'm able to do this, I'd say that anthropologists work in interdisciplinary teams at multiple sites to explore globalization, that is, capitalism. Law is the special province of socio-cultural anthropology and I am particularly grounded in the liberal ideology behind IP. I am further skilled in the utopian traditions OS comes from, and my bases in linguistics and archeology and evolution, as well as ethnography of science and medicine, help in dealing with engineers who don't think I'm a technical person. Fieldwork experience enables me to relate to the executives of multinationals, each a nation in itself, who we service. But no one asks, as long as I make sense. That week I wasn't, after I ran out Monday to bring in the hay from the back field at the farm I live on. The farmer is an old man with a bypass and the hired man was busy with his own share. Jumping in and out of a truck, climbing stacks with a bale, keeps me relaxed and happy. -

“We'll Let the Gooks Play the Indians” the Endurance of the Frontier Myth in the Hyperreality of Full Metal Jacket (Stanley Kubrick, 1987)

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 18 | 2019 Guerre en poésie, poésie en guerre “We'll let the gooks play the Indians” The Endurance of the Frontier Myth in the Hyperreality of Full Metal Jacket (Stanley Kubrick, 1987) Vincent Jaunas Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/18912 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.18912 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Vincent Jaunas, ““We'll let the gooks play the Indians””, Miranda [Online], 18 | 2019, Online since 17 April 2019, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/18912 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.18912 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. “We'll let the gooks play the Indians” 1 “We'll let the gooks play the Indians” The Endurance of the Frontier Myth in the Hyperreality of Full Metal Jacket (Stanley Kubrick, 1987) Vincent Jaunas 1 Upon their release, Stanley Kubrick’s films were often misunderstood and only acquired a cult status in the long run. Yet before Full Metal Jacket, none of them was ever accused of being uninventive. However, when in 1987 the director released his own take on the Vietnam War, influential American critic Roger Ebert considered that “this isn't a bad film but it‘s not a great film and in the recent history of movies about Vietnam Full Metal Jacket is too little and too late" (Ebert 1987). Released almost a decade after Michael Cimino's The Deer Hunter (1978) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), Kubrick’s film even came after a new trend of 1980s Vietnam films such as the Rambo franchise or Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986). -

“The Killing of Gus Hasford”

LA Weekly, June 4–10, 1993 “The Killing of Gus Hasford” By Grover Lewis 1. SEMPER GUS “The best work of fiction about the Vietnam War,” Newsweek called Gus Hasford’s The Short-Timers when it was first published in 1979. The slim hardcover sold, like most first novels, in the low thousands, but established its author as one of the premier writing talents of his generation. In the tradition of Stephen Crane, Hemingway and James Jones, the book summoned up the horrors of war in an unrelenting voice with all the potential for world-class success. Hasford’s critical stock rose even higher when Stanley Kubrick filmed the book as Full Metal Jacket. Released in 1987, the picture received one major Academy Award nomination—shared by Kubrick, Michael Herr and Hasford himself for best screen adaptation. At a stroke, the struggling, rootless young novelist entered the upper realms of “A-list” Hollywood. But in a skein of envy, spite and the inexorable grinding of bureaucratic “justice”—all of them compounded by Hasford’s own obsessive passion for books— his newfound celebrity backfired, and he was sent to jail on bizarrely exaggerated charges involving stolen and overdue library books. It all combined to kill him. Gus died alone, as he had mostly lived, in Greece on January 29 at the measly age of 45 from the complications of untreated diabetes. His death coincided eerily with the 25th anniversary of the Tet offensive, the campaign so graphically described in The Short-Timers. Two weeks after the shock of his death, 20-odd mourners had gathered in the chapel at Tacoma’s Mountain View Memorial Park. -

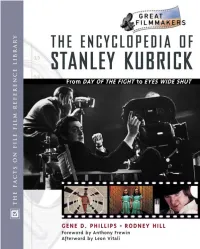

The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick

THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK GENE D. PHILLIPS RODNEY HILL with John C.Tibbetts James M.Welsh Series Editors Foreword by Anthony Frewin Afterword by Leon Vitali The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick Copyright © 2002 by Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hill, Rodney, 1965– The encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick / Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill; foreword by Anthony Frewin p. cm.— (Library of great filmmakers) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4388-4 (alk. paper) 1. Kubrick, Stanley—Encyclopedias. I. Phillips, Gene D. II.Title. III. Series. PN1998.3.K83 H55 2002 791.43'0233'092—dc21 [B] 2001040402 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K.Arroyo Cover design by Nora Wertz Illustrations by John C.Tibbetts Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

October 1, 1987

Free Films for free in Grafton- Tough Soccer team loses to Next An update on the status FiiCkS Stovall Theatre, p. 15 LOSS number one UVa., p. 18 Issue ofWJMR THURSDAY, OCTOBER 1,1987 JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY VOL. 65 NO. 10 Warren 'initiates' plans to improve student learning By Martin Romjue news editor A five-year plan designed to improve student learning at JMU is now beyond its planning stage, said JMUs vice president for academic affairs. Formerly know as the five-year plan, the program now is called the academic initiatives for excellence "to symbolize the end of planning" and the start of carrying those plans out, said Dr. Russell Warren, who originated the plan. The academic affairs office sent a 72-page report to all faculty members and administrators last month summarizing accomplishments, remaining goals and costs of separate programs in the plan. Programs include improving advising services for students, using more evaluations of how much Staff photo by MARK MANOUKIAN students learn while at JMU, requiring more liberal arts courses and developing more learning experiences Barkley and Marina Rosser are happy to be sharing their lives and their work. outside the classroom. Higher education is not known for rapid, coordinated change, Warren said. "We're trying to Rosser lives fantasy as show that a university can change quickly, but substantially." The initiatives program is unique in that it will Russian teacher at JMU change several aspects of JMU at the same time. Warren said. By Martin Romjue "My biggest adjustment is having to speak Faculty hearings were held last semester to get news editor English," Mrs. -

An Examination of the Life and Work of Gustav Hasford

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-2010 An Examination of the life and work of Gustav Hasford Matthew Samuel Ross University of Nevada Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Repository Citation Ross, Matthew Samuel, "An Examination of the life and work of Gustav Hasford" (2010). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 236. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1449240 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN EXAMINATION OF THE LIFE AND WORK OF GUSTAV HASFORD by Matthew Samuel Ross Bachelor of Arts University of California, Los Angeles 2006 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the Master of Arts in English Department of English College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2010 Copyright by Matthew Samuel Ross 2010 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE COLLEGE We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by Matthew Samuel Ross entitled An Examination of the Life and Work of Gustav Hasford be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts English John Irsfeld, Committee Chair Richard Harp, Committee Member Joseph McCullough, Committee Member Andy Fry, Graduate Faculty Representative Ronald Smith, Ph. -

Un Chaleco De Acero Título Original: the Short-Timers Gustav Hasford, 1979

Un chaleco de acero Título original: The short-timers Gustav Hasford, 1979 Traducción: Jaime Zulaika Un chaleco de acero Gustav Hasford 1979 Traducción: Jaime Zulaika Portada y maquetación: Demófilo 2019 Libros libres para una Cultura Libre p Biblioteca Libre OMEGALFA 2019 Ω - 2 - Desde sus páginas iniciales en el campamento de ins- trucción hasta el paroxismo final durante la batalla en la selva, «Un chaleco de acero» es una recreación bri- llante y salvaje del descenso a la barbarie que constitu- yó el trasfondo de la intervención norteamericana en Vietnam. La crueldad, la deshumanización y el horror han con- vertido a los protagonistas en máquinas despiadadas dedicadas a matar y a sobrevivir en el seno de la gue- rra. Con una peculiar lógica interna, han terminado por asumir su condición humana como algo perfectamente subsidiario de sus instintos y reacciones primarias de hambre, odio y venganza. Este cuadro sobrecogedor de la brutalidad bélica ha inspirado el film de Stanley Kubrick, «La chaqueta me- tálica». - 3 - Gustav Hasford UN CHALECO DE ACERO - 4 - Dedicado a JOHN C. PENNINGTON, «Penny», cabo fotógrafo de combate, Primera División de la Infantería de Marina Adiós a un soldado Adiós, soldado, el de la ruda campaña (que nosotros comparti- mos), la rápida marcha, la vida de campamento, la feroz contien- da de frentes opuestos, la larga maniobra, las batallas rojas con su carnicería, el estímulo, el juego fuerte, aterrador, hechizo del corazón valiente y viril, contigo y con los tuyos los trenes del tiempo llenos de guerra y expresión bélica. Adiós, querido camarada, tu misión has cumplido, pero yo, más belicoso, yo y este espíritu beligerante que tengo, aún empecinado en nuestra campaña, a través de caminos inexplorados, plenos de enemigos emboscados, y a través de muchas aplastantes derrotas y numerosas crisis, a menudo frenado, aquí avanzando, siempre avanzando, una guerra libro, sí, una guerra, por dejar constancia de más fieras batallas de más peso. -

Rotten Symbol Mongering: Scapegoating in Post-9/11 American War Literature

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2015 Rotten Symbol Mongering: Scapegoating in Post-9/11 American War Literature David Andrew Buchanan University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Buchanan, David Andrew, "Rotten Symbol Mongering: Scapegoating in Post-9/11 American War Literature" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1014. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1014 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. ROTTEN SYMBOL MONGERING: SCAPEGOATING IN POST-9/11 AMERICAN WAR LITERATURE __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by David A. Buchanan August 2015 Advisor: Dr. Billy J. Stratton ©Copyright by David A. Buchanan 2015 All Rights Reserved Author: David A. Buchanan Title: ROTTEN SYMBOL MONGERING: SCAPEGOATING IN POST-9/11 AMERICAN WAR LITERATURE Advisor: Dr. Billy J. Stratton Degree Date: August 2015 Abstract A rhetorical approach to the fiction of war offers an appropriate vehicle by which one may encounter and interrogate such literature and the cultural metanarratives that exist therein. My project is a critical analysis—one that relies heavily upon Kenneth Burke’s dramatistic method and his concepts of scapegoating, the comic corrective, and hierarchical psychosis—of three war novels published in 2012 (The Yellow Birds by Kevin Powers, FOBBIT by David Abrams, and Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain). -

View of the Federal Farmer, Wished for the Substantial Preservation of the State Governments, but Sought a Federal Government That Was More Than Merely Advisory

1 FOR THE COLLECTION OF A LIFETIME The process of creating one’s personal library is the pursuit of a lifetime. It requires special thought and consideration. Each book represents a piece of history, and it is a remarkable task to assemble these individual items into a collection. Our aim at Raptis Rare Books is to render tailored, individualized service to help you achieve your goals. We specialize in working with private collectors with a specific wish list, helping individuals find the ideal gift for special occasions, and partnering with representatives of institutions. We are here to assist you in your pursuit. Thank you for letting us be your guide in bringing the library of your imagination to reality. FOR MORE INFORMATION For further details regarding any of the items featured in these pages, visit our website or call 561-508-3479 for expert assistance from one of our booksellers. Raptis Rare Books | 226 Worth Avenue | Palm Beach, Florida 33480 561-508-3479 | [email protected] www.RaptisRareBooks.com Contents Opening Selections...............................................................................................2 Americana...........................................................................................................16 Religion, History & World Leaders.................................................................37 Literature.............................................................................................................50 Children’s Literature...........................................................................................80 -

Strategies of Representing Victimhood in American Narratives of the War in Vietnam

Uniwersytet Śląski w Katowicach Wydział Filologiczny Aleksandra Musiał “An American Tragedy” Strategies of Representing Victimhood in American Narratives of the War in Vietnam Rozprawa doktorska napisana pod kierunkiem: p r o m o t o r : dr hab. Leszek Drong p r o m o t o r p o m o c n ic z y : dr Marcin Sarnek Katowice 2018 Table of Contents Introduction: Secret Histories..................................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1: Vietnam Syndromes: Symptoms & Contexts 1.1. The American cultural narrative of Vietnam...............................................................................................17 1.2. Repudiating the 1960s................................................................................................................................... 23 1.3. Squandering Vietnam’s subversive potential.............................................................................................. 34 Chapter 2: “War Is as Natural as the Rains”: Myth and Representations of the Vietnamese landscape 2.1. History..............................................................................................................................................................65 2.2. Myth..................................................................................................................................................................75 2.2.1. “The sins of the forest are alive in the jungle”.....................................................................................82