Espying Balletic Heights by Lynn Matluck Brooks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sleeping Beauty Untouchable Swan Lake In

THE ROYAL BALLET Director KEVIN O’HARE CBE Founder DAME NINETTE DE VALOIS OM CH DBE Founder Choreographer SIR FREDERICK ASHTON OM CH CBE Founder Music Director CONSTANT LAMBERT Prima Ballerina Assoluta DAME MARGOT FONTEYN DBE THE ROYAL BALLET: BACK ON STAGE Conductor JONATHAN LO ELITE SYNCOPATIONS Piano Conductor ROBERT CLARK ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE Concert Master VASKO VASSILEV Introduced by ANITA RANI FRIDAY 9 OCTOBER 2020 This performance is dedicated to the late Ian Taylor, former Chair of the Board of Trustees, in grateful recognition of his exceptional service and philanthropy. Generous philanthropic support from AUD JEBSEN THE SLEEPING BEAUTY OVERTURE Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE UNTOUCHABLE EXCERPT Choreography HOFESH SHECHTER Music HOFESH SHECHTER and NELL CATCHPOLE Dancers LUCA ACRI, MICA BRADBURY, ANNETTE BUVOLI, HARRY CHURCHES, ASHLEY DEAN, LEO DIXON, TÉO DUBREUIL, BENJAMIN ELLA, ISABELLA GASPARINI, HANNAH GRENNELL, JAMES HAY, JOSHUA JUNKER, PAUL KAY, ISABEL LUBACH, KRISTEN MCNALLY, AIDEN O’BRIEN, ROMANY PAJDAK, CALVIN RICHARDSON, FRANCISCO SERRANO and DAVID YUDES SWAN LAKE ACT II PAS DE DEUX Choreography LEV IVANOV Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY Costume designer JOHN MACFARLANE ODETTE AKANE TAKADA PRINCE SIEGFRIED FEDERICO BONELLI IN OUR WISHES Choreography CATHY MARSTON Music SERGEY RACHMANINOFF Costume designer ROKSANDA Dancers FUMI KANEKO and REECE CLARKE Solo piano KATE SHIPWAY JEWELS ‘DIAMONDS’ PAS DE DEUX Choreography GEORGE BALANCHINE Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY -

Royal Opera House Performance Review 2006/07

royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 1 Royal Opera House Performance Review 2006/07 The Royal Ballet - The Royal Opera royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 2 Contents 01 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S 02 TH E ROYA L OP E R A PE R F O R M A N C E S royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 3 3 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S 2 0 0 6 / 2 0 0 7 01 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 4 4 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S 2 0 0 6 / 2 0 0 7 GI S E L L E NU M B E R O F PE R F O R M A N C E S 6 (15 matinee and evening 19, 20, 28, 29 April) AV E R A G E AT T E N D A N C E 91% CO M P O S E R Adolphe Adam, revised by Joseph Horovitz CH O R E O G R A P H E R Marius Petipa after Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot SC E N A R I O Théophile Gautier after Heinrich Meine PRO D U C T I O N Peter Wright DE S I G N S John Macfarlane OR I G I N A L LI G H T I N G Jennifer Tipton, re-created by Clare O’Donoghue STAG I N G Christopher Carr CO N D U C T O R Boris Gruzin PR I N C I PA L C A S T I N G Giselle – Leanne Benjamin (2) / Darcey Bussell (2) / Jaimie Tapper (2) Count Albrecht – Edward Watson (2) / Roberto Bolle (2) / Federico Bonelli (2) Hilarion – Bennet Gartside (2) / Thiago Soares (2) / Gary Avis (2) / Myrtha – Marianela Nuñez (1) / Lauren Cuthbertson (3) (1- replacing Zenaida Yanowsky 15/04/06) / Zenaida Yanowsky (1) / Vanessa Palmer (1) royal_ballet_royal_opera.qxd 18/9/07 14:15 Page 5 5 TH E ROYA L BA L L E T PE R F O R M A N C E S 2 0 0 6 / 2 0 0 7 LA FI L L E MA L GA R D E E NU M B E R O F PE R F O R M A N C E S 10 (21, 25, 26 April, 1, 2, 4, 5, 12, 13, 20 May 2006) AV E R A G E AT T E N D A N C E 86% CH O R E O G R A P H Y Frederick Ashton MU S I C Ferdinand Hérold, freely adapted and arranged by John Lanchbery from the 1828 version SC E N A R I O Jean Dauberval DE S I G N S Osbert Lancaster LI G H T I N G John B. -

Ashton Triple Cast Sheet 16 17 ENG.Indd

THE ROYAL BALLET Approximate timings DIRECTOR KEVIN O’HARE Live cinema relay begins at 7.15pm, ballet begins at 7.30pm FOUNDER DAME NINETTE DE VALOIS OM CH DBE FOUNDER CHOREOGRAPHER The Dream 55 minutes SIR FREDERICK ASHTON OM CH CBE Interval FOUNDER MUSIC DIRECTOR CONSTANT LAMBERT Symphonic Variations 20 minutes PRIMA BALLERINA ASSOLUTA Interval DAME MARGOT FONTEYN DBE Marguerite and Armand 35 minutes The live relay will end at approximately 10.25pm Tweet your thoughts about tonight’s performance before it starts, THE DREAM during the intervals or afterwards with #ROHashton FREE DIGITAL PROGRAMME SYMPHONIC Royal Opera House Digital Programmes bring together a range of specially selected films, articles, pictures and features to bring you closer to the production. Use promo code ‘FREEDREAM’ to claim yours (RRP £2.99). VARIATIONS roh.org.uk/publications 2016/17 LIVE CINEMA SEASON MARGUERITE OTELLO WEDNESDAY 28 JUNE 2017 AND ARMAND 2017/18 LIVE CINEMA SEASON THE MAGIC FLUTE WEDNESDAY 20 SEPTEMBER 2017 LA BOHÈME TUESDAY 3 OCTOBER 2017 CHOREOGRAPHY FREDERICK ASHTON ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND MONDAY 23 OCTOBER 2017 THE NUTCRACKER TUESDAY 5 DECEMBER 2017 CONDUCTOR EMMANUEL PLASSON RIGOLETTO TUESDAY 16 JANUARY 2018 TOSCA WEDNESDAY 7 FEBRUARY 2018 ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE THE WINTER’S TALE WEDNESDAY 28 FEBRUARY 2018 CONCERT MASTER VASKO VASSILEV CARMEN TUESDAY 6 MARCH 2018 NEW MCGREGOR, THE AGE OF ANXIETY, DIRECTED FOR THE SCREEN BY NEW WHEELDON TUESDAY 27 MARCH 2018 ROSS MACGIBBON MACBETH WEDNESDAY 4 APRIL 2018 MANON THURSDAY 3 MAY 2018 LIVE FROM THE SWAN LAKE TUESDAY 12 JUNE 2018 ROYAL OPERA HOUSE WEDNESDAY 7 JUNE 2017, 7.15PM For more information about the Royal Opera House and to explore our work further, visit roh.org.uk/cinema THE DREAM SYMPHONIC VARIATIONS Oberon, King of the Fairies, has quarrelled with his Queen, Titania, who refuses to MUSIC CÉSAR FRANCK hand over the changeling boy. -

And We Danced Episode 3 Credits

AND WE DANCED WildBear Entertainment, ABC TV and The Australian Ballet acknowledge the Traditional Owners of country throughout Australia and recognise their continuing connection to land, waters and culture. We pay our respects to their Elders past and present. EPISODE THREE Executive Producers Veronica Fury Alan Erson Michael Tear Development Producer Stephen Waller INTERVIEWEES Margot Anderson Dimity Azoury Peter F Bahen Lisa Bolte Adam Bull Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chengwu Guo David Hallberg Ella Havelka Steven Heathcote AM Marilyn Jones OBE Ako Kondoo David McAllister AC Graeme Murphy AO Stephen Page AO Lisa Pavane Colin Peasley OAM Marilyn Rowe AM OBE Amber Scott Hugh Sheridan Fiona Tonkin OAM Elizabeth Toohey Emma Watkins Michael Williams SPECIAL THANKS TO David McAllister AC David Hallberg Nicolette Fraillon AM 1 Artists of The Australian Ballet past and present Artists of Bangarra Dance Theatre past and present Orchestra Victoria Opera Australia Orchestra The Australian Ballet School Tony Iffland Janine Burdeu The Wiggles The Langham Hotel Melbourne Brett Ludeman, David Ward ARCHIVE SOURCES The Australian Ballet ABC Archives National Film and Sound Archive Associated Press Getty The Apiary The Wiggles International Arts Newspix Bolshoi Ballet American Ballet Theater FOOTAGE The Australian Ballet Year of Limitless Possibilities, 2020 Brand Film Artists of The Australian Ballet Valerie Tereshchenko, Robyn Hendricks, Dimity Azoury, Callum Linnane, Jake Mangakahia Choreography David McAllister AM Cinematography Brett Ludeman and Ryan Alexander Lloyd Produced by Robyn Fincham and Brett Ludeman Filmed on location at Mundi Mundi Station, via Silverton NSW The Living Desert Sculpture Park, Junction Mine, The Imperial Fine Accommodation, Broken Hill NSW. -

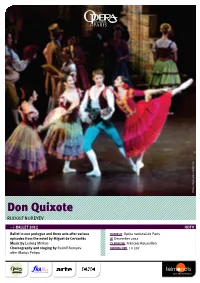

Don Quixote RUDOLF NUREYEV

s i r a P e d l a n o i t a n a r é p O : o t o h P © Don Quixote RUDOLF NUREYEV > BALLET 2012 HDTV Ballet in one prologue and three acts after various FILMED AT Opéra national de Paris episodes from the novel by Miguel de Cervantès IN December 2012 Music by Ludwig Minkus TV DIRECTOR François Roussillon Choreography and staging by Rudolf Nureyev RUNNING TIME 1 x 120’ after Marius Petipa Don Quixote artistic information DESCRIPTION “The Knight of the Sad Face” and his faithful squire, Sancho Panza, are mixed up in the wild love affairs of the stunning Kitri and the seductive Basilio in a richly colourful, humorous and virtuoso ballet. Marius Petipa’s Don Quixote premiered in Moscow in 1869 with music by Ludwig Minkus and met with resounding success from the start. The novelty lay within its break from the supernatural universe of romantic ballet. Written as if it were a play for the theatre, the work had realistic heroes and a solidly structured plot and scenes. The libretto and the choreography were handed down without interruption in Russia, but Petipa’s version remained unknown in the west for a long time. In 1981, Rudolf Nureyev introduced his own version of the work into the Paris Opera’s repertoire. While retaining the great classical pages and the strong, fiery dances, the choreographer gave greater emphasis to the comic dimension contriving a particularly lively and light-hearted production. In 2002, Alexander Beliaev and Elena Rivkina were invited to create new sets and costumes specially for the Opera Bastille. -

For Immediate Release Media Contact

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT: Jacalyn Lawton Public Relations Manager [email protected] [email protected] HOUSTON BALLET PROUDLY ANNOUNCES ITS 2021-2022 SEASON HOUSTON, TEXAS [May 3, 2021] — Houston Ballet proudly announces its 2021-2022 season and return to live performances at its home theater at Wortham Theater Center this fall. After canceling part of its 2019-2020 season and the entirety of its 2020-2021 season due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Houston Ballet is thrilled to share the joy of its jubilant return to the stage. “We’re overjoyed to return the Wortham Theater Center stage and bring back our talented artists and supporters into the same space to share these joyous occasions once more,” says Stanton Welch AM, Houston Ballet Artistic Director. “We’ve grown from this difficult time and have been inspired by our community to keep creating art that reflects the diverse and innovative city we call home.” The 2021-2022 season lineup includes an array of works by world-renowned artists, continuing to showcase Houston as a mecca for global talent. In addition to Welch’s own works being presented, patrons will enjoy distinct stylings from choreographers such as George Balanchine, Trey McIntyre and Houston Ballet Principal Dancers Melody Mennite and Connor Walsh. Accompanying the visually stunning performances, audiences will hear iconic scores from famous composers such as Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Leo Delibes, in addition to works set to sounds from music legends like David Bowie. “Our subscribers and supporters are as thrilled as we are to return to live performances in September, and we’re counting on the community’s continued financial support as we return after two back-to-back crises,” says Jim Nelson, Houston Ballet Executive Director. -

Music, Dance and Swans the Influence Music Has on Two Choreographies of the Scene Pas D’Action (Act

Music, Dance and Swans The influence music has on two choreographies of the scene Pas d’action (Act. 2 No. 13-V) from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake Naam: Roselinde Wijnands Studentnummer: 5546036 BA Muziekwetenschap BA Eindwerkstuk, MU3V14004 Studiejaar 2017-2018, block 4 Begeleider: dr. Rebekah Ahrendt Deadline: June 15, 2018 Universiteit Utrecht 1 Abstract The relationship between music and dance has often been analysed, but this is usually done from the perspective of the discipline of either music or dance. Choreomusicology, the study of the relationship between dance and music, emerged as the field that studies works from both point of views. Choreographers usually choreograph the dance after the music is composed. Therefore, the music has taken the natural place of dominance above the choreography and can be said to influence the choreography. This research examines the influence that the music has on two choreographies of Pas d’action (act. 2 no. 13-V), one choreographed by Lev Ivanov, the other choreographed by Rudolf Nureyev from the ballet Swan Lake composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky by conducting a choreomusicological analysis. A brief history of the field of choreomusicology is described before conducting the analyses. Central to these analyses are the important music and choreography accents, aligning dance steps alongside with musical analysis. Examples of the similarities and differences between the relationship between music and dance of the two choreographies are given. The influence music has on these choreographies will be discussed. The results are that in both the analyses an influence is seen in the way the choreography is built to the music and often follows the music rhythmically. -

East by Northeast the Kingdom of the Shades (From Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Music by Ludwig Minkus Staged by Glenda Lucena

2013/2014 La Bayadère Act II | Airs | Donizetti Variations Photo by Paul B. Goode, courtesy of the Paul Taylor Dance Company East by Spring Ballet Northeast Seven Hundred Fourth Program of the 2013-14 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents Spring Ballet: East by Northeast The Kingdom of the Shades (from Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Music by Ludwig Minkus Staged by Glenda Lucena Donizetti Variations Choreography by George Balanchine Music by Gaetano Donizetti Staged by Sandra Jennings Airs Choreography by Paul Taylor Music by George Frideric Handel Staged by Constance Dinapoli Michael Vernon, Artistic Director, IU Ballet Theater Stuart Chafetz, Conductor Patrick Mero, Lighting Design _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, March Twenty-Eighth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, March Twenty-Ninth, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, March Twenty-Ninth, Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Kingdom of the Shades (from Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Staged by Glenda Lucena Music by Ludwig Minkus Orchestration by John Lanchbery* Lighting Re-created by Patrick Mero Glenda Lucena, Ballet Mistress Violette Verdy, Principals Coach Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Premiere: February 4, 1877 | Imperial Ballet, Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre, St. Petersburg Grand Pas de Deux Nikiya, a temple dancer . Alexandra Hartnett Solor, a warrior. Matthew Rusk Pas de Trois (3/28 and 3/29 mat.) First Solo. Katie Zimmerman Second Solo . Laura Whitby Third -

The Royal Ballet School Summer Performances White Lodge | 23 June - 10 July 2021 Welcome

THE ROYAL BALLET SCHOOL SUMMER PERFORMANCES WHITE LODGE | 23 JUNE - 10 JULY 2021 WELCOME It is my great pleasure to welcome you to White Lodge for The Royal Ballet School Summer Performances. This has been an extraordinary and unforgettable year of challenge and adaptation for The Royal Ballet School. Today’s performance is a tribute to the resilience and creativity shown by our students and staff throughout that time. Seeing their determination to succeed, separated from each other for so much of the year and unable to train or teach in the studios they love, has been a powerful inspiration. I am delighted that following the sadness of cancelled performances in 2020, we finally have the chance to come together to celebrate their work. I wanted our students to enjoy dancing in front of an audience again, and the best way to do this was to give them as many chances to perform on stage as possible. The School’s teams have, with spectacular effort, put together nine different programmes over 32 performances. Each of the eight year groups will have the chance to dance in their own dedicated performances, culminating in a final collective, socially distanced, performance at the Royal Opera House. I am proud to say that the dedication and hard work of our remarkable community of dancers and teachers mean we can continue to call the School one of the very best in the world. Across this season, dancers of all ages are performing a range of work that shows off the skills they have learnt through their training. -

The Late John Lanchbery Was Commissioned by Rudolf Nureyev to Arrange the Score for His Production of Don Quixote

Olivia Bell, 2007 Photography David Kelly MUSIC NOTE The late John Lanchbery was commissioned by Rudolf Nureyev to arrange the score for his production of Don Quixote. Here, Lanchbery explains his approach to the music. Conductor John Lanchbery, 1997 Photography Jim McFarlane In Russia in the second half of the 19th century, unadventurous, and just occasionally uninteresting. Like the scores for all 19th-century ballets that have the growth and popularity of the arts resulted in the His unending fund of melody was at its best in waltz- stayed in the Russian repertoire, Don Quixote has long immigration of a number of non-Russian musicians time, obviously because of his early life in Vienna; ago been tinkered with, added to and subtracted from who served a useful purpose until such time as the when in doubt he wrote in this rhythm, and it is fun to without mercy. When Nureyev commissioned me to do great Russian school of composers came into force. note that in his tragic ballet La Bayadère, a story of a completely new version of it for (coincidentally) the fatal snake-bite, unrequited love and a haunted temple Vienna Opera House in 1966, I therefore suffered no In the ballet of the time the music had above all to be in mythological India, the best musical moment is pangs of conscience in trying to improve the hotch- melodic, easily remembered, and simple in its form when a corps de ballet of beautiful Hindu lady-ghosts potch which has survived as Minkus’ score. I adapted and rhythmic pattern. -

Stephanie Jordan Re-Visioning Nineteenth-Century Music Through Ballet

Stephanie Jordan Re-Visioning Nineteenth-Century Music Through Ballet. The Work of Sir Frederick Ashton Sir Frederick Ashton, founder choreographer of The Royal Ballet, was a noted exponent of nineteenth-century music, especially ballet music. Consider his Les Rendezvous (1933, Daniel-François-Esprit Auber), Les Patineurs (1937, Giacomo Meyerbeer), and Birthday Offering (1956, Alexander Glazunov); then his two/three act ballets La Fille mal gardée (1960, mainly Ferdinand Hérold), Sylvia (1952, Léo Delibes), and The Two Pigeons (1961, André Messager); and finally the two dances to music fromLa Source(Delibes and Léon Minkus), training pieces for the Royal Academy of Dancing (rad) Solo Seal examinations (cir- ca 1956). Nearly all these ballets are to French ballet music for ballet-divertissements within, as well as independent from, opera. Yet we could add Ashton’s settings ofpassages from Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake, his series of ballets to scores by Franz Liszt, The Dream (1964) to incidental music for Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream by Felix Mendelssohn that sounds as if composed for dance, and AMonth in the Country (1976) to Frédéric Chopin (based on the play by Turgenev) which, as we shall see later, has a number of links with nineteenth-century Paris. Month is set to three early Chopin scores for piano and orchestra that are full of dances and dance rhythms. (Ashton maintained a penchant for more recent French music too: he set Darius Milhaud, Paul Dukas, Erik Satie, Francis Poulenc, Claude Debussy and, on a number of occasions, Maurice Ravel.)1 Most of these ballets are well-known Ashton, amongst his finest work, and never lost from the repertory. -

La Fille Mal Gardée

FERDINAND HÉROLD LA FILLE BAMALLET INL TWO GARDÉE ACTS MARIANELA NUÑEZ ∙ CARLOS AcOSTA WILLIAM TUCKET ∙ JONATHAN HOWELLS ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE CONDUCTED BY ANTHONY TwINER STAGED BY FREDERICK ASHTON FERDINAND HÉROLD LA FILLE MAL GARDÉE Ballet company The Royal Ballet Ever since its triumphant premiere in 1960, Frederick Ashton’s Choreographer Frederick Ashton La Fille mal gardée has been treasured as one of his happiest cre- Orchestra Orchestra of the ations - his artistic tribute to nature, and an expression of his Royal Opera House feelings for his beloved Suffolk countryside. Marianela Nuñez Conductor Anthony Twiner and Carlos Acosta perfectly portray the young lovers Lise and Colas, determined to thwart the plans of Widow Simone to mar- Lise Marianela Nuñez ry off her wayward daughter to Alain, the simple son of wealthy Colas Carlos Acosta Farmer Thomas. Widow Simone William Tuckett Alain Jonathan Howells Osbert Lancaster’s colourful, picture-book designs, along with Thomas David Drew Ferdinand Herold’s tuneful score, arranged by John Lanchbery, provide the perfect setting for Ashton’s blissfully bucolic ballet, Video Director Ross McGibbon complete with haywain, pony, maypole and ribbons, a cockerel and his chickens and, of course, the famous clog dance, here Length: 108' wonderfully led by William Tuckett as the irascible but lovable Shot in HDTV 1080/50i Widow Simone. Cat. no. A 020 50036 “La fille mal gardée is sheer perfection. Nuñez and Acosta are A production of BBC unsurpassable respectively in the feminine grace and masculine in association with the confidence of Ashton’s Lise and Colas, and their mimetic skills Royal Opera House, Covent Garden are delicious.” (BBC Music Magazine) World Sales: All rights reserved · credits not contractual · Different territories · Photos: © Bill Cooper · Flyer: luebbeke.com Flyer: · Cooper contractual Bill Different Photos: © territories credits · not rights · All reserved · Tel.