ALLSTATE INDEMNITY CO. V. RUIZ, 899 So.2D 1121

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Allstate Sustainability Re

Allstate sustainability report PURPOSE our shared purpose As the Good Hands… We empower customers with protection to help them achieve their hopes and dreams. We provide affordable, simple and connected protection solutions. We create opportunity for our team, economic value for our shareholders and improve communities. Overview Our Values • Integrity is non-negotiable. • Inclusive Diversity & Equity values and leverages unique identities with equitable opportunity and rewards. • Collective Success is achieved through empathy and prioritizing enterprise outcomes ahead of individuals. Our Operating Standards • Focus on Customers by anticipating and exceeding service expectations at low costs. • Be the Best at protecting customers, developing talent and running our businesses. • Be Bold with original ideas using speed and conviction to beat the competition. • Earn Attractive Returns by providing customer value, proactively accepting risk and using analytics. Our Behaviors • Collaborate early and often to develop and implement comprehensive solutions and share learnings. • Challenge Ideas to leverage collective expertise, evaluate multiple alternatives and create the best path forward. • Provide Clarity for expected outcomes, decision authority and accountability. • Provide Feedback that is candid, actionable, independent of hierarchy and safe. Allstate 2020 Sustainability Report 1 The story of Our Shared Purpose The story of Our Shared Purpose began years ago, when Tom Wilson became CEO with the goal of making Allstate more customer focused and faster moving. A dozen senior leaders of the corporation went through what became the Energy for Life program to articulate their personal purpose and build plans to achieve it. In , Allstate created a similar plan, and Our Shared Vision became the company’s new story. -

In the Court of Appeals of the State of Mississippi No. 2017

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI NO. 2017-CA-01380-COA ALLSTATE INSURANCE COMPANY APPELLANT/ CROSS-APPELLEE v. GLORIA MILLSAPS, INDIVIDUALLY AND IN APPELLEES/ HER CAPACITY AS THE ADMINISTRATOR CROSS-APPELLANTS OF THE ESTATE OF WILLIE MILLSAPS, DECEASED DATE OF JUDGMENT: 08/11/2017 TRIAL JUDGE: HON. EDDIE H. BOWEN COURT FROM WHICH APPEALED: JASPER COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT, SECOND JUDICIAL DISTRICT ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANT: J. COLLINS WOHNER JR. DAVID GARNER MICHAEL B. WALLACE ROBERT R. STEPHENSON JR. ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEES: SAMUEL STEVEN McHARD PAUL MANION ANDERSON NATURE OF THE CASE: CIVIL - CONTRACT DISPOSITION: REVERSED AND REMANDED - 05/12/2020 MOTION FOR REHEARING FILED: MANDATE ISSUED: EN BANC. McDONALD, J., FOR THE COURT: ¶1. Willie and Gloria Millsaps’s home, located in Jones County, Mississippi, burned on September 3, 2015. After investigating the fire, their insurer, “Allstate”1 denied the claim. 1 In this case there are two “Allstate” entities: Allstate Insurance Company and Allstate Vehicle and Property Insurance Company. Unless otherwise indicated, we use the term “Allstate” to reference Allstate Insurance Company. The Millsapses sued Allstate for breach of contract and other contract-related claims in the Circuit Court of Jasper County, Mississippi. A jury found in favor of the Millsapses against Allstate Insurance Company on the Breach of Contract claim and awarded them a total of $970,000 in damages. After reconvening and hearing testimony on punitive damages, the jury awarded the Millsapses an additional $230,000 in emotional damages ($115,000 for each), and $100,000 in punitive damages. The two verdicts totaled $1,300,000. -

The Sidelight, February 2020

THE SIDELIGHT Published by KYSWAP, Inc., subsidiary of KYANA Charities 3821 Hunsinger Lane Louisville, KY 40220 February 2020 Printed by: USA PRINTING & PROMOTIONS, 4109 BARDSTOWN ROAD, Ste 101, Louisivlle, KY 40218 KYANA REGION AACA OFFICERS President: Fred Trusty……………………. (502) 292-7008 Vice President: Chester Robertson… (502) 935-6879 Sidelight Email for Articles: Secretary: Mark Kubancik………………. (502) 797-8555 Sandra Joseph Treasurer: Pat Palmer-Ball …………….. (502) 693-3106 [email protected] (502) 558-9431 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Alex Wilkins …………………………………… (615) 430-8027 KYSWAP Swap Meet Business, etc. Roger Stephan………………………………… (502) 640-0115 (502) 619-2916 (502) 619-2917 Brian Hill ………………………………………… (502) 327-9243 [email protected] Brian Koressel ………………………………… (502) 408-9181 KYANA Website CALLING COMMITTEE KYANARegionAACA.com Patsy Basham …………………………………. (502) 593-4009 SICK & VISITATION Patsy Basham …………………………………. (502) 593-4009 THE SIDELIGHT MEMBERSHIP CHAIRMAN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF KYSWAP, Roger Stephan………………………………… (502) 640-0115 INC. LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY HISTORIAN Marilyn Ray …………………………………… (502) 361-7434 Deadline for articles is the 18th of preceding month in order to have it PARADE CHAIRMAN printed in the following issue. Articles Howard Hardin …………………………….. (502) 425-0299 from the membership are welcome and will be printed as space permits. CLUB HOUSE RENTALS Members may advertise at no charge, Ruth Hill ………………………………………… (502) 640-8510 either for items for sale or requests to obtain. WEB MASTER Editorials and/or letters to the editor Interon Design …………………………………(502) 593-7407 are the personal opinion of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the CHAPLAIN official policy of the club. Ray Hayes ………………………………………… (502) 533-7330 LIBRARIAN Jane Burke …………………………………….. (502) 500-8012 From the President Fred Trusty Last month I reported that we lost 17 members in 2019 for various reasons. -

60 Charged in Fall Insurance Fraud Sweep

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ October 2018 60 Charged in Fall Insurance Fraud Sweep October 2017. On November 13, Harper allegedly filed a claim indicating that 18 items were stolen from his vehicle. Harper • On October 9, 2018, allegedly provided Mark Folino was Allstate with fraudulent arrested in Lawrence receipts for mink coats County. According to and jackets the criminal complaint, purportedly valued at on March 13, 2018, at more than $43,000. approximately 12:49 Investigators spoke to the owner of the men’s PM, Folino rear-ended a store listed on the receipts. The owner State Farm insured allegedly advised that his store did not issue vehicle which was the receipts and did not sell coats at such high- attempting to make a end prices. Allstate denied the claim. Harper left hand turn into a was charged with one count of Insurance Fraud driveway. The complaint stated that when the (F3), one count of Theft by Deception (F3), one accident occurred, Folino was listed as an count of Forgery (F3) and one count of excluded driver on the Progressive Criminal Use of a Communication Facility (F3). Insurance vehicle policy shared by Folino and his wife. Approximately one hour after the • On October 25, 2018, accident, Folino’s wife allegedly added him to Kennesha Watson the policy as a covered driver. Folino allegedly was arrested in contacted Progressive later that day and filed Montgomery County. a claim for the accident, stating that the crash According to the occurred after he was added to the policy as a criminal complaint, on covered driver. However, the complaint stated September 20, 2017, that investigators reviewed the Pennsylvania Watson’s uninsured State Police incident report which confirmed vehicle was involved that the loss occurred prior to the policy in an accident. -

Mtr of B.Z. Chiropractic, P.C. V Allstate Insurance Company

Supreme Court of the State of New York Appellate Division: Second Judicial Department D66577 I/afa AD3d Argued - September 21, 2020 MARK C. DILLON, J.P. BETSY BARROS FRANCESCA E. CONNOLLY LINDA CHRISTOPHER, JJ. 2019-04454 OPINION & ORDER 2019-04456 In the Matter of B.Z. Chiropractic, P.C., respondent, v Allstate Insurance Company, appellant. (Index No. 719878/18) APPEALS by Allstate Insurance Company, in a hybrid proceeding pursuant to CPLR 5225 to compel the turnover of funds held in a bank account in the name of Allstate Insurance Company and an action for declaratory relief, from (1) an order of the Supreme Court (Laurence L. Love, J.), entered March 8, 2019, in Queens County, and (2) an order of the same court entered April 22, 2019. The order entered March 8, 2019, insofar as appealed from, granted that branch of the petition/complaint which was for a judgment declaring that a judgment in favor of B.Z. Chiropractic, P.C., and against Allstate Insurance Company entered November 15, 2001, in the Civil Court, Queens County, accrued interest at the rate of 2% per month compounded and denied the cross petition of Allstate Insurance Company, inter alia, to dismiss the proceeding/action. The order entered April 22, 2019, denied the motion of Allstate Insurance Company for leave to renew and reargue its cross petition. Peter C. Merani, P.C., New York, NY (Adam Waknine of counsel), for appellant. Amos Weinberg (Lynn Gartner Dunne, LLP, Mineola, NY [Kenneth L. Gartner] of July 21, 2021 Page 1. MATTER OF B.Z. CHIROPRACTIC, P.C. -

Kaiser - Frazer Page 1 Service Parts

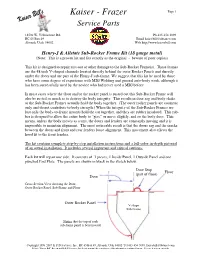

Kaiser - Frazer Page 1 Service Parts 18530 W. Yellowstone Rd. Ph 435-454-3098 HC 65 Box 49 Email [email protected] Altonah, Utah 84002 Web http://www.kaiserbill.com Henry-J & Allstate Sub-Rocker Frame Kit (18 gauge metal) (Note: This is a proven kit and fits exactly as the original - beware of poor copies) This kit is designed to repair rust-out or other damage to the Sub-Rocker Frame(s). These frames are the 48 inch V-shaped channels located directly behind the outer Rocker Panels and directly under the doors and are part of the Henry-J sub-frame. We suggest that this kit be used by those who have some degree of experience with MIG Welding and general auto-body work, although it has been successfully used by the novice who had never used a MIG before. In most cases where the floor and/or the rocker panel is rusted out this Sub-Rocker Frame will also be rusted so much as to destroy the body integrity. This results in door sag and body shake as the Sub-Rocker Frames actually hold the body together. (The outer rocker panels are cosmetic only and do not contribute to body strength.) When the integrity of the Sub-Rocker Frames are lost only the body-to-frame mounts hold the car together, and they are rubber insulated. This rub- ber is designed to allow the entire body to “give” or move slightly, and so the body does. This means, unless the body moves as a unit, the doors and fenders are constantly moving and it is impossible to maintain alignment. -

FILE FORM # SIZE PAGE DATE COLOR Accessories Kaiser

DATE FORM # PAGE SIZE COLOR FILE Accessories No Date Kaiser Accessories, Featuring a complete line of 1951-55 0 8 1/4 x 5 1/2 Sepia-toned Facts Book Copyright 1951 Henry J: Salesman Facts 1951-117 104 8 x 7 1/4 White / Blue / Black Cover Miscellaneous No Date Kaiser-Henry J: Kaiser Frazer Graphic Willow Run 1953 1953-34 16 11 x 15 Part Color No Date Kaiser | Henry J: 1953 Colors, color chips and tissue insert 1953-39 4 10 1/2 x 8 1/2 Green / Black / White Owners Manual Copyright Aug Henry J: Owners packet, includes owners manual, 2-sided sheet, 1951-116 1950 #740343; service policy # 740537; owners card #740538, in envelope #740577, plus Air Conditioner and Radio Instructions, if equipped 0 4 x 8 1/2 Rose / Black / White No Date RF28-9999 Allstate: Owners packet, includes owners manual, service policy 1952-29 and owners card in envelope, plus Air Conditioner and Radio Instructions, if equipped 20 5 x 7 Red / Black / White Copyright 1952 734988 Henry J: Owners Packet, includes owners manual, 2-sided sheet, 1952-47 Service Policy #740537; owners card #740538; in envelope #740987, plus Air Conditioner and Radio Instructions, if equipped 0 4 x 8 1/2 Blue / Black / White RF28-9999 Allstate: Allstate: Owners packet, includes owner manual, service 1953-44 policy and owners card, in envelope, plus Air Conditioner and Radio Instructions, if equipped 20 5 x 7 Orange / Black / White 740880 Henry J: Owners Packet, includes owners manual, #740880, 1953-79 service policy #745630; owners card #745629;,Care of Bright Trim card, plus Air Conditioner and -

Texas Court Update Regarding Recent Opinions Dealing with Personal Automobile Insurance Policies 2006-07

TEXAS COURT UPDATE REGARDING RECENT OPINIONS DEALING WITH PERSONAL AUTOMOBILE INSURANCE POLICIES 2006-07 JAMES J. DOYLE III RAYMOND T. FISCHER Cooper & Scully, P.C. 900 Jackson Street, Suite 100 Dallas, TX 75202 State Bar of Texas 14th ANNUAL COVERAGE AND BAD FAITH SEMINAR March 30, 2007 Dallas, Texas D/678332.1 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CASES Allstate Indem. Co. v. Collier, 983 S.W.2d 342 (Tex. App.—Waco 1998, pet. dism'd by agr.)....................................2 Allstate Ins. Co. v. Hunt, 469 S.W.2d 151 (Tex.1971).....................................................................................9, 10 Allstate v. Hyman, No. 06-05-00064-CV, 2006 WL 694014 (Tex. App.—Texarkana March 21, 2006, no pet.) .................6, 7, 11 Battaglia v. Alexander, 177 S.W.3d 893 (Tex.2005)...........................................................................................3 Brainard v. Trinity Universal Insurance Co., 50 Tex. Sup. Ct. J. 271, 2006 WL 3751572 (Tex. Dec. 22, 2006) ............................1, 2 Henson v. Southern Farm Bureau Cas. Ins. Co., 17 S.W.3d 652 (Tex. 2000)............................................................................................2 Jankowiak v. Allstate Property & Cas. Ins. Co., 201 S.W.3d 200 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 2006, no pet.).............................10 Lewis v. Allstate Ins. Co., No. 09-05-225-CV, 2006 WL 665790 (Tex. App.—Beaumont, March 16, 2006, no pet.).........................12 Lopez v. Farmers Texas County Mut. Ins. Co., No. 06-06-00024-CV, 2007 WL 703496 (Tex.App.—Texarkana Mar. 9, 2007, no pet.) .................................................................................................................7 Menix v. Allstate Indem. Co., 83 S.W.3d 877 (Tex.App.—Eastland 2002, pet. denied) ..............................................2 Mid-Century Ins. Co. of Texas v. Daniel, No. 07-05-0014-CV, 2007 WL 414330 (Tex. -

Universal Underwriters Insurance Company V. Allstate Insurance Comp Any, a Corporation : Brief of Appellant Utah Supreme Court

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons Utah Supreme Court Briefs (1965 –) 1968 Universal Underwriters Insurance Company v. Allstate Insurance Comp Any, a Corporation : Brief of Appellant Utah Supreme Court Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/uofu_sc2 Part of the Law Commons Original Brief submitted to the Utah Supreme Court; funding for digitization provided by the Institute of Museum and Library Services through the Library Services and Technology Act, administered by the Utah State Library, and sponsored by the S.J. Quinney Law Library; machine- generated OCR, may contain errorsL.E. Midgley; Attorney for RespondentHanson & Garrett; Attorneys for Appellant Recommended Citation Brief of Appellant, Universal Underwriters v. Allstate Insurance, No. 11176 (Utah Supreme Court, 1968). https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/uofu_sc2/110 This Brief of Appellant is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Supreme Court Briefs (1965 –) by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF UTAH UNIVERSAL UNDERWRITERS INSURANCE COMPANY, a Corporation Plaintiff and AppeUant, Case No. vs. 11176 ALLSTATE INSURANCE COMP ANY, a Corporation, Defendant and Respondent. BRIEF OF APPELLANT Appeal from the Judgment of the Third Judicial Court for Salt Lake County Honorable Stewart M. Hanson, Judge HANSON & GARRETT W. BRENT WILCOX, Esq. 520 Continental Bank Bldg. Salt Lake City, Utah Attorneys f<Yr Appellant L. E. MIDGLEY, Esq. 702 El Paso Natural Gas Building Salt Lake City, Utah Attorney for Respondent = f~L~ED \J1 1'.'i 1 :; igEir~ Sponsored by the S.J. -

Your Right to Repair NOT THEIRS

THE CHOICE IS YOURS. NOT ALL PARTS ARE Your right to repair NOT THEIRS. CREATED EQUAL. You’re in the driver seat when it comes to By requesting new GM Genuine Parts and Knowledge is power. That’s true even when it choosing replacement parts for your vehicle. ACDelco OE parts, you’re choosing to keep your comes to collision repair. Knowing your rights* But some insurance policies may only provide GM a GM. Because only GM Genuine Parts and following an accident can help ensure that compensation for aftermarket collision parts. ACDelco GM OE parts are engineered to the your vehicle gets back on the road in a proper, Those parts may not provide the original fit, form, exact specifications of your Chevrolet, Buick, complete, and safe manner. and function of GM Genuine Parts and ACDelco GMC, or Cadillac vehicle. GM OE parts. You have the right to choose your Manufactured to work with GM vehicle safety repair facility, including a GM Collision systems, no other aftermarket parts can ensure Repair Network (CRN) facility. OE compatibility. And no other parts are designed, engineered, tested, and backed by You have the right to request new General Motors. GM Genuine Parts and ACDelco GM ASK YOUR INSURANCE PROVIDER Original Equipment (OE) parts. THESE KEY QUESTIONS: • Does my current policy include new OE parts You have the right to a proper repair coverage? using GM-approved procedures. • Will the parts used to repair my vehicle be new OE parts? • Is a rental car provided during repairs under my policy? • Do I have to take my vehicle to a drive-in claims center, or can I take it to a dealer? *Rights vary by state. -

Injury, Collision, & Theft Losses

INJURY,COLLISION, & THEFT LOSSES By make and model, 1996-98 models September 1999 HIGHWAY LOSS DATA INSTITUTE 1005 N. Glebe Rd. Arlington, VA 22201 703/247-1600 Fax 703/247-1595 Internet: www.carsafety.org The Highway Loss Data Institute (HLDI) is a nonprofit public service COMPARISON WITH DEATH RATES organization. It is closely associated with and funded through the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, which is wholly supported by Collisions that result in serious and fatal occupant injuries are rela- auto insurers. HLDI gathers, processes, and publishes data on the tively rare, so they have only a small influence on the insurance injury ways in which insurance losses vary among different kinds of vehicles. results reported in this table. (The results in the table are dominated by the relatively frequent low to moderate severity collisions and asso- ciated injuries.) A separate report, published periodically by the In- GUIDE TO THIS REPORT surance Institute for Highway Safety, is based on fatal crashes. It sum- marizes driver deaths per 10,000 registered vehicle years by make The table inside summarizes the recent insurance injury, collision, and and model. theft losses of passenger cars, pickups, and utility vehicles. Results are based on the loss experience of 1996-98 models from their first sales Vehicles with high death rates often have high frequencies of insur- through June 1999. For vehicles newly introduced or redesigned dur- ance claims for occupant injuries. For example, small two- and four- ing these years, the results are based on the most recent model years door cars typically have high death rates and higher-than-average for which the vehicle designs were unchanged — either 1997-98 or insurance injury claims experience. -

Allstate Property & Casualty Insurance Co. V. Trujillo, 2014 IL App (1St)

Illinois Official Reports Appellate Court Allstate Property & Casualty Insurance Co. v. Trujillo, 2014 IL App (1st) 123419 Appellate Court ALLSTATE PROPERTY AND CASUALTY INSURANCE Caption COMPANY, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. DOLORES TRUJILLO, Defendant-Appellant. District & No. First District, Sixth Division Docket No. 1-12-3419 Rule 23 Order filed December 20, 2013 Rule 23 Order withdrawn February 21, 2014 Opinion Filed February 28, 2014 Held In an action arising from an automobile collision involving multiple (Note: This syllabus tortfeasors, the appellate court reversed the trial court’s judgment constitutes no part of the ruling that plaintiff insurer was entitled to set off defendant’s claim for opinion of the court but underinsured motorist benefits under one of the policies plaintiff has been prepared by the issued with the amounts plaintiff paid under the bodily injury Reporter of Decisions coverage of the same policy, since under the circumstances, defendant for the convenience of was allowed to seek both bodily injury and underinsured benefits the reader.) under the same policy, but defendant was not entitled to a windfall or double recovery, and therefore, the cause was remanded to ensure defendant was not awarded more than the damages suffered. Decision Under Appeal from the Circuit Court of Cook County, No. 12-CH-02130; the Review Hon. Mary Anne Mason, Judge, presiding. Judgment Reversed and remanded. Counsel on Ronald Fishman and Kenneth A. Fishman, both of Fishman & Appeal Fishman, Ltd., of Chicago, for appellant. Peter C. Morse and Cynthia Ramirez, both of Morse Bolduc & Dinos, LLC, of Chicago, for appellee. Panel JUSTICE REYES delivered the judgment of the court, with opinion.