Damming the Agatsuma River| an Exploration of Changing Space and Place in Kawarayu, Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safety Inspections of Fisheries Products on Radioactive Materials

(Provisional translation) [16 March] Safety inspections of fisheries products on radioactive materials Sericulture and Horticulture Division, Gunma Prefecture The Gunma Prefectural Government conducted inspections on radioactive materials in the samples of landlocked salmon, whitespotted char and Japanese dace taken from 14 rivers, Japanese smelt taken from one lake, and ayu sweetfish taken from one fish farm in the prefecture. The result of the inspection, obtained on 16 March, showed that the level of radioactive cesium was below the provisional regulation value in all the samples. However, in response to implementation of the new Standard Limits on 1 April, the Gunma Prefectural Government and relevant Fisheries Cooperatives have consented to release Japanese dace caught in Nakuta River, landlocked salmon and whitespotted char caught in Imagawa River, Kenjo River and Nurukawa River, and not to serve such fish for consumption. The Prefectural Government and Fisheries Cooperatives also have consented to collect Japanese smelt caught in Akagi-onuma Lake, and not to serve them for consumption. 1. Inspection area Karasu River (Takasaki City) Amisawa River (Katashina Village) Ogawa River (Katashina Village) Nurigawa River (Katashina Village) Nerigawa River (Numata City) Akatani River (Minakami Town) Hirakawa River (Numata City) Kurihara River (Numata City) Katashina River (Numata City) Nakuta River (Takayama Village) Imagawa River (Higashi-agatsuma Town) Kenjo River (Higashi-agatsuma Town) Nurukawa River (Higashi-agatsuma Town) Kumakawa -

Outdoor Club Japan (OCJ) 国際 アウトドア・クラブ・ジャパン Events

Outdoor Club Japan (OCJ) 国際 アウトドア・クラブ・ジャパン Events Norikuradake Super Downhill 10 March Friday to 12 March Monday If you are not satisfied ski & snowboard in ski area. You can skiing from summit. Norikuradake(3026m)is one of hundred best mountain in Japan. This time is good condition of backcountry ski season. Go up to the summit of Norikuradake by walk from the top of last lift(2000m). Climb about 5 hours and down to bottom lift(1500m) about 50 min. (Deta of last time) Transport: Train from Shinjuku to Matsumoto and Taxi from Matsumoto to Norikura-kogen. Return : Bus from Norikura-kogen to Sinshimashima and train to Shinjuku. Meeting Time & Place : 19:30 Shijuku st. platform 5 car no.1 for super Azusa15 Cost : About Yen30000 Train Shinjuku to matsumoto Yen6200(ow) but should buy 4coupon ticket each coupon Yen4190 or You can buy discount ticket shop in town price is similar. (price is non-reserve seat) Taxi about Yen13000 we will share. Return bus Yen1300 and local train Yen680. Inn Yen14000+tax 2 overnight 2 breakfast 1 dinner (no dinner Friday) Japanese room and hot spring! Necessary equipment : Skiers & Telemarkers need a nylon mohair skin. Snowboarders need snowshoes. Crampons(over 8point!) Clothes: Gore-tex jacket and pants, fleece, hut, musk, gloves, sunglasses, headlamp, thermos, lunch, sunscreen If you do not go up to the summit, you can enjoy the ski area and hot springs. 1 day lift pass Yen4000 Limit : 12persons (priority is downhill from summit) In Japanese : 026m)の頂上からの滑降です。 ゲレンデスキーに物足りないスキーヤー、スノーボーダー向き。 山スキーにいいシーズンですが、天気次第なので一応土、日と2日間の時間をとりました。 -

Pdf/Rosen Eng.Pdf Rice fields) Connnecting Otsuki to Mt.Fuji and Kawaguchiko

Iizaka Onsen Yonesaka Line Yonesaka Yamagata Shinkansen TOKYO & AROUND TOKYO Ōu Line Iizakaonsen Local area sightseeing recommendations 1 Awashima Port Sado Gold Mine Iyoboya Salmon Fukushima Ryotsu Port Museum Transportation Welcome to Fukushima Niigata Tochigi Akadomari Port Abukuma Express ❶ ❷ ❸ Murakami Takayu Onsen JAPAN Tarai-bune (tub boat) Experience Fukushima Ogi Port Iwafune Port Mt.Azumakofuji Hanamiyama Sakamachi Tuchiyu Onsen Fukushima City Fruit picking Gran Deco Snow Resort Bandai-Azuma TTOOKKYYOO information Niigata Port Skyline Itoigawa UNESCO Global Geopark Oiran Dochu Courtesan Procession Urabandai Teradomari Port Goshiki-numa Ponds Dake Onsen Marine Dream Nou Yahiko Niigata & Kitakata ramen Kasumigajo & Furumachi Geigi Airport Urabandai Highland Ibaraki Gunma ❹ ❺ Airport Limousine Bus Kitakata Park Naoetsu Port Echigo Line Hakushin Line Bandai Bunsui Yoshida Shibata Aizu-Wakamatsu Inawashiro Yahiko Line Niigata Atami Ban-etsu- Onsen Nishi-Wakamatsu West Line Nagaoka Railway Aizu Nō Naoetsu Saigata Kashiwazaki Tsukioka Lake Itoigawa Sanjo Firework Show Uetsu Line Onsen Inawashiro AARROOUUNNDD Shoun Sanso Garden Tsubamesanjō Blacksmith Niitsu Takada Takada Park Nishikigoi no sato Jōetsu Higashiyama Kamou Terraced Rice Paddies Shinkansen Dojo Ashinomaki-Onsen Takashiba Ouchi-juku Onsen Tōhoku Line Myoko Kogen Hokuhoku Line Shin-etsu Line Nagaoka Higashi- Sanjō Ban-etsu-West Line Deko Residence Tsuruga-jo Jōetsumyōkō Onsen Village Shin-etsu Yunokami-Onsen Railway Echigo TOKImeki Line Hokkaid T Kōriyama Funehiki Hokuriku -

Collection of Products Made Through Affrinnovation ‐ 6Th Industrialization of Agriculture,Forestry and Fisheries ‐

Collection of Products made through AFFrinnovation ‐ 6th Industrialization of Agriculture,Forestry and Fisheries ‐ January 2016 Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries In Japan, agricultural, forestry and fisheries workers have been making efforts to raise their income by processing and selling their products in an integrated manner to create added value. These efforts are called the “AFFrinnovation,” and agricultural, forestry and fisheries workers throughout the country have made the best use of inventiveness to produce a variety of products. This book introduces products that were created through the efforts to promote the AFFrinnovation. We hope this book would arouse your interest in the AFFrinnovation in Japan. Notes ○ Information contained in this book is current as of the editing in January 2016, and therefore not necessarily up to date. ○ This book provides information of products by favor of the business operators as their producers. If you desire to contact or visit any of business operators covered in this book, please be careful not to disturb their business activities. [Contact] Food Industrial Innovation Division Food Industry Affairs Bureau Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries URL:https://www.contact.maff.go.jp/maff/form/114e.html Table of Contents Hokkaido Name of Product Name Prefecture Page Business Operator Tomatoberry Juice Okamoto Nouen Co., Ltd. Hokkaido 1 Midi Tomato Juice Okamoto Nouen Co., Ltd. Hokkaido 2 Tokachi Marumaru Nama Cream Puff (fresh cream puff) Okamoto Nouen Co., Ltd. Hokkaido 3 (tomato, corn, and azuki bean flavors) Noka‐no Temae‐miso (Farm‐made fermented soybean Sawada Nojo LLC Hokkaido 4 paste) Asahikawa Arakawa Green Cheese Miruku‐fumi‐no‐ki (milky yellow) Hokkaido 5 Bokujo LLC Asahikawa Arakawa Farm Green Cheese Kokuno‐aka (rich red) Hokkaido 6 LLC Menu at a farm restaurant COWCOW Café Oono Farm Co., Ltd. -

44. Kusatsu-Shiranesan)

(44. Kusatsu-Shiranesan) 44. Kusatsu-Shiranesan Continuously Monitored by JMA Latitude: 36°38'38" N, Longitude: 138°31'40" E, Elevation: 2,160 m (Shiranesan) (Elevation Point) Latitude: 36°37'06" N, Longitude: 138°31'40" E, Elevation: 2,165 m (Shiranesan) (Triangulation Point) Overview of Kusatsu-Shiranesan taken from the west side on August 10, 2011 by the Japan Meteorological Agency Summary Kusatsu-Shiranesan is a stratovolcano which was formed asymmetrically on Neogene basement rock which slopes downwards to the southeast. A group of pyroclastic cones, including Shiranesan, Ainomine, and Motoshiranesan, which stretch from the north to the south, are located in its highest western area. To the south and east of these cones, andesitic lava flows cover an area of several km from the summit. Further downhill there is a dacitic pyroclastic flow plateau. The SiO2 content of the andesite and dacite is between 53.7 and 64.2 wt %. 3 crater lakes are arranged from northeast to southwest at the summit of the Shiranesan pyroclastic cone. They are named Mizugama, Yugama, and Karegama. All historical eruptions were occurred in the Shiranesan summit area. All recent eruptive activity consists of phreatic explosions. The volcano is prone to producing lahars. The volcano has many hot springs, such as Kusatsu Onsen, and solfatara which generates H2S. 1 (44. Kusatsu-Shiranesan) Photos Fissure Eruption on the southeast flank of Yugama on February 2, 1942 (Minakami, et al., 1942) Eruption at Kusatsu-Shiranesan, taken from the southwest on December 29, 1982. Courtesy of J. Ossaka. 2 (44. Kusatsu-Shiranesan) Yugama, taken from the north side on April 13, 2010 by the Japan Meteorological Agency From front to back: Mizugama, Yugama, Karegama Overview of Yugama taken from the south side on April 13, 2010 by the Japan Meteorological Agency 3 (44. -

Suica Pasmo Network

To Matō Kassemba Ienaka Tōbu-kanasaki Niregi Momiyama Kita-kanuma Itaga Shimo-goshiro Myōjin Imaichi Nikkō Line To Aizu-Wakamatsu To Sendai To Fukushima Jōban Line To Haranomachi Watarase Keikoku Railway Nikkō Ban-etsu-East Line Shin-kanuma Niigata Area Akagi Tanuma Tada Tōbu Nikkō Line Minami- Tōbu-nikkō Iwaki / Network Map To Chuo-Maebashi ※3 To Kōriyama Kuzū Kami- Uchigō To Murakami ★ Yashū-ōtsuka Kuniya Omochanomachi Nishikawada Esojima utsunomiya Tōhoku Line Tōbu Sano Line TsurutaKanumaFubasami Shin-fujiwara Jomo Electric Railway Yoshimizu Shin-tochigi Shimo- imaichi Shin-takatokuKosagoeTobu WorldKinugawa-onsen SquareKinugawa-kōen Yumoto ■Areas where Suica /PASMO can be used Yashū-hirakawa Mibu Tōbu Utsunomiya Line Yasuzuka Kuroiso Shibata Tōhoku Tōhoku Shinkansen imaichi Line Aizu Kinugawa Aioi Nishi-Kiryu Horigome Utsunomiya Line Shimotsuke-Ōsawa Tōbu Kinugawa Line Izumi Daiyamukō Ōkuwa Railway Yagantetsudo To Naoetsu To Niigata Omata YamamaeAshikagaAshikaga TomitaFlower Park Tōbu-utsunomiya Ueda Yaita Nozaki Nasushiobara Nishi-Shibata Nakaura Echigo TOKImeki Railway Ishibashi Suzumenomiya Nakoso Kunisada Iwajuku Shin-kiryū Kiryū Ryōmō Line Sano Iwafune Ōhirashita Tochigi Omoigawa To Naganoharakusatsuguchi ShikishimaTsukudaIwamotoNumataGokan KamimokuMinakami Shin-ōhirashita Jichi Medical Okamoto Hōshakuji Karasuyama Ujiie Utsunomiya Kamasusaka Kataoka Nishi-Nasuno Ōtsukō Sasaki To Echigo-Yuzawa Azami Sanoshi To Motegi Utsunomiya Line Line Uetsu LineTsukioka Jōmō-Kōgen ★ Shizuwa University Isohara Shibukawa Jōetsu Line Yabuzuka -

Spatial and Temporal Models of J¯Omon Settlement

Spatial and Temporal Models of Jomon¯ Settlement Enrico R. Crema A Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Archaeology University College London January 2013 Declaration I, Enrico Ryunosuke Crema, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 ”Ce qui est simple est toujours faux. Ce qui ne l’est pas est inutilisable” (P. Valery) ”All models are wrong, but some are useful” (George E.P. Box) Abstract The Jomon¯ culture is a tradition of complex hunter-gatherers which rose in the Japanese archipelago at the end of the Pleistocene (ca. 13,000 cal BP) and lasted until the 3rd millennium cal BP. Recent studies increasingly suggest how this long cultural persistence was characterised by repeated episodes of change in settle- ment pattern, primarily manifested as cyclical transitions between nucleated and dispersed distributions. Although it has been suggested that these events corre- late with population dynamics, shifts in subsistence strategies, and environmental change, to date there have been very few attempts to provide a quantitative anal- ysis of spatio-temporal change in Jomon settlement and its possible causes. This thesis is an attempt to fill that lacuna by adopting a twin-track approach to the problem. First, two case studies from central Japan have been examined us- ing a novel set of methods, which have been specifically designed to handle the intrinsic chronological uncertainty which characterises most prehistoric data. This facilitated the application of a probabilistic framework for quantitatively assessing the available information, making it possible to identify alternating phases of nu- cleated and dispersed pattern during a chronological interval between 7000 and 3300 cal BP. -

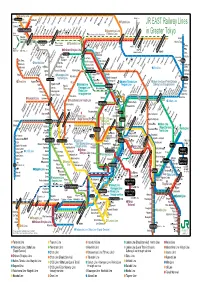

JR Railways Lines in Greater Tokyo

- 31 Joetsu- Line - Nikko- Line Shibukawa 渋川 Maebashi Kiryu Sano 32 - - Agatsuma Line Yagihara - Omata Tomita Ryomo Line oshima KomagataIsesaki Iwajuku Iwafune Tochigi JR EAST Railway Lines Kunisada Ashikaga Maebashi Yamamae Ohirashita Omoigawa Gumma-Soja 新前橋 Shim-Maebashi 17 - Utsunomiya Line Joetsu Kita- ( - ) in Greater Tokyo Shinkansen Ino KuraganoShimmachiJimboharaHonjoOkabeFukayaKagohara GyodaFukiage KonosuKonosuKitamotoOkegawaKita-AgeoAgeo Tohoku.Yamagata.Akita Shinkansen Tohoku Line KoganeiJichiidaiIshibashiSuzumenomiya Takasaki Miyahara tonyamachi Hitachi - akasaki Honjowaseda Joetsu. Nagano Hitachi-Taga 高崎 Kumagaya 18 Takasaki Line Oyama Utsunomiya Ujiie Yaita T 本庄早稲田 熊谷 Shinkansen Line Toro Kuki - Koga Nogi 小山 宇都宮 Nozaki Kuroiso Omika Omiya Shin- OkamotoHoshakuji Kataoka Nagano Higashi- Hasuda Shiraoka Higashi- 3 - Shiraoka Kurihashi Mamada 宝積寺 Tokai Shinkansen Shin-etsu Line Shonan-Shinjuku Line Kamasusaka Saitama- Karasuyama Line Nishi-NasunoNasushiobara那須塩原 Sawa odo Kawagoe Washinomiya Kita-Fujiokaansho Y orii Shintoshin T Y 川越 Omiya Suigun Line Katsuta Kodama Takezawa Nishi- Kita-Yono Yono Matsuhisa Kawagoe 大宮 Oku-Tama Gumma-Fujioka Kita-Urawa Yuki Mito 16 - Orihara Nisshin Yono-Hommachi Otabayashi Yuki Iwase Hachiko Line Ogawamachi Matoba Sashiogi Urawa Niihari Yamato Haguro Inada Shiromaru Minami-Yono Higashi- Tamado Fukuhara 水戸 Kairakuen Myokaku Kasahata Kawashima Shimodate (Extra) Hatonosu Minami-Furuya Naka-Urawa 33 Mito Line Nishi-Urawa 南浦和 Higashi-Urawa Higashi- Akatsuka Kori Ogose Musashi-Takahagi Musashi-Urawa Minami-Urawa Kawaguchi Kasama 武蔵浦和 Kawai Moro 20 Kawagoe Line Kita-Toda Warabi Shim-Misato Uchihara MitakeSawaiIkusabataFutamataoIshigamimaeHinatawadaMiyanohira 高麗川 Kita-Asaka Minami-oshigaya 友部 Ome - Toda Nishi-Kawaguchi K Komagawa Hachiko Line Yoshikawa Shishido Tomobe - Toda-Koen Kawaguchi - Misato - 14 Ome Line Higashi-Ome 4 Keihin-Tohoku- Line 23 Joban Line [Local Train]-Chiyoda Niiza - Ukimafunado 22 Iwama Kabe Higashi-Hanno 19 Saikyo- Line. -

Jprail-Timetable-Kamiki.Pdf

JPRail.com train timetable ThisJPRail.com timetable contains the following trains: JPRail.com 1. JR limited express trains in Hokkaido, Hokuriku, Chubu and Kansai area 2. Major local train lines in Hokkaido 3. Haneda airport access trains for the late arrival and the early departure 4. Kansai airport access trains for the late arrival and the early departure You may find the train timetables in the links below too. 1. JR East official timetable (Hokkaido, Tohoku, Akita, Yamagata, Joetsu and Hokuriku Shinkansens, Narita Express, Limited Express Azusa, Odoriko, Hitachi, Nikko, Inaho, and major joyful trains in eastern Japan) 2.JPRail.comJR Kyushu official timetable (Kyushu Shinkansen, JPRail.com Limited Express Yufuin no Mori, Sonic, Kamome, and major D&S trains) Timetable index (valid until mid March 2020) *The timetables may be changed without notice. The Limited Express Super Hokuto (Hakodate to Sapporo) 4 The Limited Express Super Hokuto (Sapporo to Hakodate) 5 JPRail.comThe Limited Express Suzuran (Muroran to Sapporo) JPRail.com6 The Limited Express Suzuran (Sapporo to Muroran) 6 The Limited Express Kamui and Lilac (Sapporo to Asahikawa) 7 The Limited Express Kamui and Lilac (Asahikawa to Sapporo) 8 The Limited Express Okhotsk and Taisetsu 9 The Limited Express Super Ozora and Super Tokachi (Sapporo to Obihiro and Kushiro) 10 The Limited Express Super Ozora and Super Tokachi (Obihiro and Kushiro to Sapporo) 11 JPRail.comThe Limited Express Soya and Sarobetsu JPRail.com12 Hakodate line local train between Otaru and Oshamambe (Oshamambe -

THE GUNMA BANK REPORT 2020 the GUNMA BANK REPORT Integrated Report

Disclosure magazine [main part] magazine [main Disclosure Integrated Report Integrated The Gunma Bank, Ltd. THE GUNMA BANK REPORT 2020 THE GUNMA BANK REPORT Integrated Report Disclosure magazine [main part] Published in July 2020 Edited by Public Relations Office, Corporate Planning Department, The Gunma Bank, Ltd. 194 Motosojamachi, Maebashi, Gunma 371-8611, Japan Phone: +81-(0)27-252-1111 (key number) The Gunma Bank, Ltd. Corporate Philosophy It is our mission to take actions that will foster the development of regional communities. As a member of the regional community, we are committed to strengthen- ing a relationship of trust with all community members and playing a central role in promoting prosperity within local regions. To this end, we will strive to improve financial services and continue healthy growth while expanding our areas of activity. Our primary goal is to support regional communities in their efforts to develop industries, promote culture and build a prosperous life. The foundation of our business is to strengthen a creative relationship with our customers. We highly value close ties with our customers and always strive to create what we believe is best for them. Our job starts at this point by pursuing what we can do to support them. It is our goal to establish a future together with our customers. Our operations are based on the motto “Be a good citizen first to become a good entrepreneur.” Our first goal is for each employee to be a good citizen. It is the first step in building empathy and trust with our customers. In doing this, we can actively take part in society by acting as honorable people. -

Joetsu Shinkansen<For Tokyo> Joetsu Shinkansen<From Tokyo> Joetsu Line<For Takasaki Or Ueno> Joetsu Line<Fro

Joetsu Shinkansen<for Tokyo> Joetsu Line<for Takasaki or Ueno> Echigo Jomo Ueno Tokyo Echigo Minakami Minakami Numata Shibukawa Shin- Train Name Niigata Takasaki Kumagaya Omiya (arr.) Track Train Name Starting station Doai Tirminal -Yuzawa -Kogen (arr.) (arr.) -yuzasa (Arrival) (Departure) (arr.) (arr.) Maebashi(arr.) Max-Tanigawa No.400 6:07 6:20 6:37 6:56 7:09 7:30 7:36 23 Joetsu Line(Local) 5:04 5:22 5:43 5:57 Takasaki 6:08 Max-Tanigawa No.402 7:10 7:23 7:40 7:59 8:14 8:34 8:40 23 Joetsu Line(Local) 5:56 6:13 6:34 6:50 Takasaki 7:01 Max-Tanigawa No.404 7:44 7:57 8:14 8:37 8:50 9:10 9:16 22 Joetsu Line(Local) 6:19 6:36 6:57 7:12 Takasaki 7:23 Toki No.306 7:15 8:04 8:17 8:34 8:53 9:06 9:26 9:32 22 Joetsu Line(Local) Ishiuchi 6:05 6:12 6:38 6:50 Max-Toki No.308 7:45 8:36 8:49 9:06 9:25 9:38 9:58 10:04 20 Joetsu Line(Local) 6:53 7:10 7:31 7:47 Takasaki 7:58 Max-Tanigawa No.406 9:21 9:35 9:51 10:13 10:26 10:46 10:52 21 Joetsu Line(Local) 7:32 7:49 8:11 8:26 Takasaki 8:38 Max-Tanigawa No.408 10:28 10:41 11:01 11:21 11:34 11:54 12:00 22 Joetsu Line(Local) 8:20 8:37 8:57 9:12 Takasaki 9:26 Max-Tanigawa No.410 11:12 11:25 11:42 12:01 12:14 12:34 12:40 20 Joetsu Line(Local) Echigoyuzawa 8:13 8:13 8:39 8:51 Asama No.522 (Nagano11:15) - - 12:03 → 12:30 12:50 12:56 20 Joetsu Line(Local) 8:57 9:14 9:37 9:52 Takasaki 10:03 Tanigawa No.412 12:09 12:22 12:42 13:01 13:14 13:34 13:40 21 Joetsu Line(Local) 9:38 9:55 10:16 10:30 Takasaki 10:41 Asama No.524 (Nagano12:18) - - 13:06 → 13:30 13:50 13:56 21 Joetsu Line(Local) 10:34 10:51 11:12 11:26 Takasaki 11:37 Tanigawa No.414 13:09 13:22 13:42 14:01 14:14 14:34 14:40 22 Limited Express Kusatsu No.2 Manza-Kazawa 10:49 - - 11:46dep. -

Fukushima Nuclear Disaster – Implications for Japanese Agriculture and Food Chains

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Fukushima nuclear disaster – implications for Japanese agriculture and food chains Bachev, Hrabrin and Ito, Fusao Institute of Agricultural Economics, Sofia, Tohoku University, Sendai 3 September 2013 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/49462/ MPRA Paper No. 49462, posted 03 Sep 2013 08:50 UTC Fukushima Nuclear Disaster – Implications for Japanese Agriculture and Food Chains1 Hrabrin Bachev, Professor, Institute of Agricultural Economics, Sofia, Bulgaria2 Fusao Ito, Professor, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan 1. Introduction On March 11, 2011 at 14:46 JST the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred with the epicenter around 70 kilometers east of Tōhoku. It was the most powerful recorded earthquake ever hit Japan with a magnitude of 9.03 Mw. The earthquake triggered powerful tsunami that reached heights of up to 40 meters in Miyako, Iwate prefecture and travelled up to 10 km inland in Sendai area. The earthquake and tsunami caused many casualties and immense damages in North-eastern Japan. According to some estimates that is the costliest natural disaster in the world history [Kim]. Official figure of damages to agriculture, forestry and fisheries alone in 20 prefectures amounts to 2,384.1 billion yen [MAFF]. The earthquake and tsunami caused a nuclear accident3 in one of the world’s biggest nuclear power stations - the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, Okuma and Futaba, Fukushima prefecture. After cooling system failure three reactors suffered large explosions and level 7 meltdowns leading to releases of huge radioactivity into environment [TEPCO]. Radioactive contamination has spread though air, rains, dust, water circulations, wildlife, garbage disposals, transportation, and affected soils, waters, plants, animals, infrastructure, supply and food chains in immense areas.