A Pioneer Exotic Tree Search for the Douglas-Fir Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

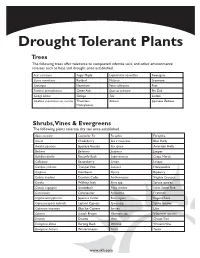

Drought Tolerant Plants

Drought Tolerant Plants Trees The following trees offer tolerance to compacted, infertile soils, and other environmental stresses such as heat and drought once established. Acer saccarum Sugar Maple Liquidambar styraciflua Sweetgum Cercis canadensis Redbud Platanus Sycamore Crataegus Hawthorn Pyrus calleryana Pear Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash Quercus palustris Pin Oak Ginkgo biloba Ginkgo Tilia Linden Gleditsia triacanthos var. inermis Thornless Zelkova Japanese Zelkova Honeylocust Shrubs, Vines & Evergreens The following plants tolerate dry soil once established. Abies concolor Concolor Fir Forsythia Forsythia Aronia Chokeberry Ilex x meservae Blue Holly Aucuba japonica Japanese Aucuba Ilex opaca American Holly Berberis Barberry Juniperus Juniper Buddleia davidii Butterfly Bush Lagerstroemia Crape Myrtle Callicarpa Beautyberry Liriope Liriope Campsis radicans Trumpet Vine Lonicera Honeysuckle Carpinus Hornbeam Myrica Bayberry Cedrus deodara Deodara Cedar Parthenocissus Virginia Creeper Corylus Walking Stick Picea spp. Spruce species Cotinus coggygria Smokebush Pinus cembra Swiss Stone Pine Cotoneaster Cotoneaster Pyracantha Firethorn Cryptomeria japonica Japanese Cedar Rosa rugosa Rugosa Rose Cupressocyparis leylandii Leyland Cypress Spirea spp. Spirea species Cupressus arizonica Blue Ice Cypress Syringa Lilac Cytissus Scotch Broom Viburnum spp. Viburnum species Deutzia Deutzia Vitex Chaste Tree Euonymus alatus Burning Bush Wisteria Wisteria Vine Euonymus fortunei Wintercreeper Yucca Yucca www.skh.com Perennials & Grasses The following -

Pije 14 Jeffrey Pine-Incense

PIJE 14 JEFFREY PINE-INCENSE-CEDAR/HUCKLEBERRY OAK Pinus jeffreyi-Calocedrus decurrens/Quercus vaccinifolia PIJE-CADE27/QUVA (N=13; FS=13) Distribution. This Association occurs on the Applegate and Ashland Ranger Districts, Rogue River National Forest and the Galice and Illinois Valley Ranger Districts, Siskiyou National Forest. It may also occur on the Ashland and Grants Pass Resource Areas, Medford District, Bureau of Land Management. Distinguishing Characteristics. This is a relatively high elevation Jeffrey pine association and is the coolest of the Jeffrey pine associations. Huckleberry oak and incense-cedar are usually present. Soils. Parent material is serpentine, with one occurrence of peridotite. Surface gravel and rock content averages 26 and 36 percent cover, respectively, while exposed bedrock cover averages 5 percent. Based on two plots sampled, soils are deep (greater than 40 inches) and well drained. Surface texture is silty clay loam, with 8 to 25 percent gravel, 35 to 50 percent cobbles and stones, and 32 percent PIJE 15 clay. Subsurface texture is silty clay loam, with 5 percent gravel, 40 percent cobbles and stones, and 32 to 35 percent clay. The soil moisture regime is probably xeric and the soil temperature regime is probably frigid. Soils classify to the following subgroups: Dystric Xerochrept and Typic Xerochrept. Environment. Elevation averages 3990 feet. Aspect is variable, although generally not northerly. Slope averages 33 percent with a range of 5 to 68 percent. Slope position ranges from ridgetops down to the middle one-third of the slope. Vegetation Composition and Structure. Total species richness is low for the Series, averaging 27 species. -

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

1151CIRC.Pdf

CIRCULAR 153 MAY 1967 OBSERVATIONS on SPECIES of CYPRESS INDIGENOUS to the UNITED STATES Agricultural Experiment Station AUBURN UNIVERSIT Y E. V. Smith, Director Auburn, Alabama CONTENTS Page SPECIES AND VARIETIES OF CUPRESSUS STUDIED 4 GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION-- 4 CONE COLLECTION 5 Cupressus arizonica var. arizonica (Arizona Cypress) 7 Cupressus arizonica var. glabra (Smooth Arizona Cypress) 11 Cupressus guadalupensis (Tecate Cypress) 11 Cupressus arizonicavar. stephensonii (Cuyamaca Cypress) 11 Cupressus sargentii (Sargent Cypress) 12 Cupressus macrocarpa (Monterey Cypress) 12 Cupressus goveniana (Gowen Cypress) 12 Cupressus goveniana (Santa Cruz Cypress) 12 Cupressus goveniana var. pygmaca (Mendocino Cypress) 12 Cupressus bakeri (Siskiyou Cypress) 13 Cupressus bakeri (Modoc Cypress) 13 Cupressus macnabiana (McNab Cypress) 13 Cupressus arizonica var. nevadensis (Piute Cypress) 13 GENERAL COMMENTS ON GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION ---------- 13 COMMENTS ON STUDYING CYPRESSES 19 FIRST PRINTING 3M, MAY 1967 OBSERVATIONS on SPECIES of CYPRESS INDIGENOUS to the UNITED STATES CLAYTON E. POSEY* and JAMES F. GOGGANS Department of Forestry THERE HAS BEEN considerable interest in growing Cupressus (cypress) in the Southeast for several years. The Agricultural Experiment Station, Auburn University, was the first institution in the Southeast to initiate work on the cy- presses in 1937, and since that time many states have introduced Cupressus in hope of finding a species suitable for Christmas tree production. In most cases seed for trial plantings were obtained from commercial dealers without reference to seed source or form of parent tree. Many plantings yielded a high proportion of columnar-shaped trees not suitable for the Christmas tree market. It is probable that seed used in Alabama and other Southeastern States came from only a few trees of a given geo- graphic source. -

Composition of the Wood Oils of Calocedrus Macrolepis, Calocedrus

American Journal of Essential Oils and Natural Products 2013; 1 (1): 28-33 ISSN XXXXX Composition of the wood oils of Calocedrus AJEONP 2013; 1 (1): 28-33 © 2013 AkiNik Publications macrolepis, Calocedrus rupestris and Received 16-7-2013 Cupressus tonkinensis (Cupressaceae) from Accepted: 20-8-2013 Vietnam Do N. Dai Do N. Dai, Tran D. Thang, Tran H. Thai, Bui V. Thanh, Isiaka A. Ogunwande Faculty of Biology, Vinh University, 182-Le Duan, Vihn City, Nghean ABSTRACT Province, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] In the present investigation we studied the essential oil contents and compositions of three individual plants from Cupressaceae family cultivated in Vietnam. The air-dried plants were hydrodistilled and Tran D. Thang the oils analysed by GC and GC-MS. The components were identified by MS libraries and their RIs. Faculty of Biology, Vinh University, The wood essential oil of Calocedrus rupestris Aver, H.T. Nguyen et L.K. Phan., afforded oil whose 182-Le Duan, Vihn City, Nghean major compounds were sesquiterpenes represented mainly by α-cedrol (31.1%) and thujopsene Province, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] (15.2%). In contrast, monoterpene compounds mainly α-terpineol (11.6%) and myrtenal (10.6%) occurred in Calocedrus macrolepis Kurz. The wood of Cupressus tonkinensis Silba afforded oil Tran H. Thai whose major compounds were also the monoterpenes namely sabinene (22.3%), -pinene (15.2%) Institute of Ecology and Biological and terpinen-4-ol (15.5%). The chemotaxonomic implication of the present results was also Resources, Vietnam Academy of discussed. Science and Technology, 18-Hoang Quoc Viet, Cau Giay, Hanoi, Keywords: Calocedrus macrolepis; Calocedrus rupestris; α-cedrol; Cupressus tonkinensis; Essential oil Vietnam. -

Proceedings of the 56 Annual Western International Forest Disease Work

Proceedings of the 56th Annual Western International Forest Disease Work Conference October 27-31, 2008 Missoula, Montana St. Marys Lake, Glacier National Park Compiled by: Fred Baker Department of Wildland Resources College of Natural Resources Utah State University Proceedings of the 56th Annual Western International Forest Disease Work Conference October 27 -31, 2008 Missoula, Montana Holiday Inn Missoula Downtown At The Park Compiled by: Fred Baker Department of Wildland Resources College of Natural Resources Utah State University & Carrie Jamieson & Patsy Palacios S.J. and Jessie E. Quinney Natural Resources Research Library College of Natural Resources Utah State University, Logan 2009, WIFDWC These proceedings are not available for citation of publication without consent of the authors. Papers are formatted with minor editing for formatting, language, and style, but otherwise are printed as they were submitted. The authors are responsible for content. TABLE OF CONTENTS Program Opening Remarks: WIFDWC Chair Gregg DeNitto Panel: Climate Change and Forest Pathology – Focus on Carbon Impacts of Climate Change for Drought and Wildfire Faith Ann Heinsch 3 Carbon Credit Projects in the Forestry Sector: What is Being Done to Manage Carbon? What Can Be Done? Keegan Eisenstadt 3 Mountain Pine Beetle and Eastern Spruce Budworm Impacts on Forest Carbon Dynamics Caren Dymond 4 Climate Change’s Influence on Decay Rates Robert L. Edmonds 5 Panel: Invasive Species: Learning by Example (Ellen Goheen, Moderator) Is Firewood Moving Tree Pests? William -

Psme 46 Douglas-Fir-Incense

PSME 46 DOUGLAS-FIR-INCENSE-CEDAR/PIPER'S OREGONGRAPE Pseudotsuga menziesii-Calocedrus decurrens/Berberis piperiana PSME-CADE27/BEPI2 (N=18; FS=18) Distribution. This Association occurs on the Applegate, Ashland, and Prospect Ranger Districts, Rogue River National Forest, and the Tiller and North Umpqua Ranger Districts, Umpqua National Forest. It may also occur on the Butte Falls Ranger District, Rogue River National Forest and adjacent Bureau of Land Management lands. Distinguishing Characteristics. This is a drier, cooler Douglas-fir association. White fir is frequently present, but with relatively low covers. Piper's Oregongrape and poison oak, dry site indicators, are also frequently present. Soils. Parent material is mostly schist, welded tuff, and basalt, with some andesite, diorite, and amphibolite. Average surface rock cover is 8 percent, with 8 percent gravel. Soils are generally deep, but may be moderately deep, with an average depth of greater than 40 inches. PSME 47 Environment. Elevation averages 3000 feet. Aspects vary. Slope averages 35 percent and ranges between 12 and 62 percent. Slope position ranges from the upper one-third of the slope down to the lower one-third of the slope. This Association may also occur on benches and narrow flats. Vegetation Composition and Structure. Total species richness is high for the Series, averaging 44 percent. The overstory is dominated by Douglas-fir and ponderosa pine, with sugar pine and incense-cedar common associates. Douglas-fir dominates the understory. Incense-cedar, white fir, and Pacific madrone frequently occur, generally with covers greater than 5 percent. Sugar pine is common. Frequently occurring shrubs include Piper's Oregongrape, baldhip rose, poison oak, creeping snowberry, and Pacific blackberry. -

Trees for Alkaline Soil Greg Paige, Arboretum Curator

RESEARCH LABORATORY TECHNICAL REPORT Trees for Alkaline Soil Greg Paige, Arboretum Curator Common name Scientific name Common name Scientific name Amur maple Acer ginnala Norway spruce Picea abies Hedge maple Acer campestre Serbian spruce Picea omorika Norway maple Acer platanoides Lacebark pine Pinus bungeana Paperbark maple Acer griseum Limber pine Pinus flexilis Tatarian maple Acer tatarian London plane tree Platanus x acerifolia European hornbeam Carpinus betulus Callery pear Pyrus calleryana Atlas cedar Cedrus atlantica (use cultivars) Cedar of Lebanon Cedrus libani Shingle oak Quercus imbricaria Deodar cedar Cedrus deodora Bur oak Quercus macrocarpa Hackberry Celtis occidentalis English oak Quercus robur Yellowwood Cladrastis lutea Littleleaf linden Tilia cordata Corneliancherry dogwood Cornus mas Silver linden Tilia tomentosa Cockspur hawthorn Crataegus crus-galli Lacebark elm Ulmus parvifolia Washington hawthorn Crataegus Japanese zelkova Zelkova serrata phaenopyrum Leyland cypress x Cupressocyparis leylandii Hardy rubber tree Eucommia ulmoides Green ash Fraxinus pennsylvanica Founded in 1926, The Bartlett Tree Research Ginkgo Ginkgo biloba Laboratories is the research wing of Bartlett Tree Thornless honeylocust Gleditsia triacanthos ‘inermis’ Experts. Scientists here develop guidelines for all of Kentucky coffeetree Gymnocladus dioicus the Company’s services. The Lab also houses a state- Goldenraintree Koelreuteria of-the-art plant diagnostic clinic and provides vital paniculata technical support to Bartlett arborists and field staff Amur maackia Maackia amurensis for the benefit of our clients. Crabapple Malus spp. Parrotia/Persian ironwood Parrotia persica Amur cork tree Phellodendron amurense Page 1 of 1 . -

Monitoring the Emission of Volatile Organic Compounds from the Leaves of Calocedrus Macrolepis Var

J Wood Sci (2010) 56:140–147 © The Japan Wood Research Society 2009 DOI 10.1007/s10086-009-1071-z ORIGINAL ARTICLE Ying-Ju Chen · Sen-Sung Cheng · Shang-Tzen Chang Monitoring the emission of volatile organic compounds from the leaves of Calocedrus macrolepis var. formosana using solid-phase micro-extraction Received: June 10, 2009 / Accepted: August 17, 2009 / Published online: November 25, 2009 Abstract In this study, solid-phase micro-extraction through secondary metabolism in the process of growth and (SPME) fi bers coated with polydimethylsiloxane/divinyl- development. The terpenes derived from isoprenoids con- benzene (PDMS/DVB), coupled with gas chromatography/ stitute the largest class of secondary products, and they are mass spectrometry, were used to monitor the emission pat- also the most important precursors for phytoncides in forest terns of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs) materials. Phytoncides are volatile organic compounds from leaves of Calocedrus macrolepis var. formosana Florin. released by plants, and they resist and break up hazardous in situ. In both sunny and rainy weather, the circadian substances in the air. Scientists have confi rmed that phyt- profi le for BVOCs from C. macrolepis var. formosana oncides can reduce dust and bacteria in the air, and expo- leaves has three maximum emission cycles each day. This sure to essential oils from trees has also been reported to kind of emission pattern might result from the plant’s cir- lessen anxiety and depression, resulting in improved blood cadian clock, which determines the rhythm of terpenoid circulation and blood pressure reduction in humans and emission. Furthermore, emission results from the leaves animals.1 However, the chemical compositions of phyton- demonstrated that the circadian profi le of α-pinene observed cides emitted from various trees are very different and not was opposite to the profi les of limonene and myrcene, a yet clearly identifi ed. -

DOUGLAS's Datasheet

DOUGLAS Page 1of 4 Family: PINACEAE (gymnosperm) Scientific name(s): Pseudotsuga menziesii Commercial restriction: no commercial restriction Note: Coming from North West of America, DOUGLAS FIR is often used for reaforestation in France and in Europe. Properties of european planted trees (young and with a rapid growth) which are mentionned in this sheet are different from those of the "Oregon pine" (old and with a slow growth) coming from its original growing area. WOOD DESCRIPTION LOG DESCRIPTION Color: pinkish brown Diameter: from 50 to 80 cm Sapwood: clearly demarcated Thickness of sapwood: from 5 to 10 cm Texture: medium Floats: pointless Grain: straight Log durability: low (must be treated) Interlocked grain: absent Note: Heartwood is pinkish brown with veins, the large sapwood is yellowish. Wood may show some resin pockets, sometimes of a great dimension. PHYSICAL PROPERTIES MECHANICAL AND ACOUSTIC PROPERTIES Physical and mechanical properties are based on mature heartwood specimens. These properties can vary greatly depending on origin and growth conditions. Mean Std dev. Mean Std dev. Specific gravity *: 0,54 0,04 Crushing strength *: 50 MPa 6 MPa Monnin hardness *: 3,2 0,8 Static bending strength *: 91 MPa 6 MPa Coeff. of volumetric shrinkage: 0,46 % 0,02 % Modulus of elasticity *: 16800 MPa 1550 MPa Total tangential shrinkage (TS): 6,9 % 1,2 % Total radial shrinkage (RS): 4,7 % 0,4 % (*: at 12% moisture content, with 1 MPa = 1 N/mm²) TS/RS ratio: 1,5 Fiber saturation point: 27 % Musical quality factor: 110,1 measured at 2971 Hz Stability: moderately stable NATURAL DURABILITY AND TREATABILITY Fungi and termite resistance refers to end-uses under temperate climate. -

The Role of Fir Species in the Silviculture of British Forests

Kastamonu Üni., Orman Fakültesi Dergisi, 2012, Özel Sayı: 15-26 Kastamonu Univ., Journal of Forestry Faculty, 2012, Special Issue The Role of True Fir Species in the Silviculture of British Forests: past, present and future W.L. MASON Forest Research, Northern Research Station, Roslin, Midlothian, Scotland EH25 9SY, U.K. E.mail:[email protected] Abstract There are no true fir species (Abies spp.) native to the British Isles: the first to be introduced was Abies alba in the 1600s which was planted on some scale until the late 1800s when it proved vulnerable to an insect pest. Thereafter interest switched to North American species, particularly grand (Abies grandis) and noble (Abies procera) firs. Provenance tests were established for A. alba, A. amabilis, A. grandis, and A. procera. Other silver fir species were trialled in forest plots with varying success. Although species such as grand fir have proved highly productive on favourable sites, their initial slow growth on new planting sites and limited tolerance of the moist nutrient-poor soils characteristic of upland Britain restricted their use in the afforestation programmes of the last century. As a consequence, in 2010, there were about 8000 ha of Abies species in Britain, comprising less than one per cent of the forest area. Recent species trials have confirmed that best growth is on mineral soils and that, in open ground conditions, establishment takes longer than for other conifers. However, changes in forest policies increasingly favour the use of Continuous Cover Forestry and the shade tolerant nature of many fir species makes them candidates for use with selection or shelterwood silvicultural systems. -

Western Larch, Which Is the Largest of the American Larches, Occurs Throughout the Forests of West- Ern Montana, Northern Idaho, and East- Ern Washington and Oregon

Forest An American Wood Service Western United States Department of Agriculture Larch FS-243 The spectacular western larch, which is the largest of the American larches, occurs throughout the forests of west- ern Montana, northern Idaho, and east- ern Washington and Oregon. Western larch wood ranks among the strongest of the softwoods. It is especially suited for construction purposes and is exten- sively used in the manufacture of lumber and plywood. The species has also been used for poles. Water-soluble gums, readily extracted from the wood chips, are used in the printing and pharmaceutical industries. F–522053 An American Wood Western Larch (Lark occidentalis Nutt.) David P. Lowery1 Distribution Western larch grows in the upper Co- lumbia River Basin of southeastern British Columbia, northeastern Wash- ington, northwest Montana, and north- ern and west-central Idaho. It also grows on the east slopes of the Cascade Mountains in Washington and north- central Oregon and in the Blue and Wallowa Mountains of southeast Wash- ington and northeast Oregon (fig. 1). Western larch grows best in the cool climates of mountain slopes and valleys on deep porous soils that may be grav- elly, sandy, or loamy in texture. The largest trees grow in western Montana and northern Idaho. Western larch characteristically occu- pies northerly exposures, valley bot- toms, benches, and rolling topography. It occurs at elevations of from 2,000 to 5,500 feet in the northern part of its range and up to 7,000 feet in the south- ern part of its range. The species some- times grows in nearly pure stands, but is most often found in association with other northern Rocky Mountain con- ifers.