Polystylistic Features of Schnittke's Cello Sonata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: a Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras

Texas Music Education Research, 2012 V. D. Baker Edited by Mary Ellen Cavitt, Texas State University—San Marcos Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: A Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras Vicki D. Baker Texas Woman’s University The violin, viola, cello, and double bass have fluctuated in both their gender acceptability and association through the centuries. This can partially be attributed to the historical background of women’s involvement in music. Both church and society rigidly enforced rules regarding women’s participation in instrumental music performance during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In the 1700s, Antonio Vivaldi established an all-female string orchestra and composed music for their performance. In the early 1800s, women were not allowed to perform in public and were severely limited in their musical training. Towards the end of the 19th century, it became more acceptable for women to study violin and cello, but they were forbidden to play in professional orchestras. Societal beliefs and conventions regarding the female body and allure were an additional obstacle to women as orchestral musicians, due to trepidation about their physiological strength and the view that some instruments were “unsightly for women to play, either because their presence interferes with men’s enjoyment of the female face or body, or because a playing position is judged to be indecorous” (Doubleday, 2008, p. 18). In Victorian England, female cellists were required to play in problematic “side-saddle” positions to prevent placing their instrument between opened legs (Cowling, 1983). The piano, harp, and guitar were deemed to be the only suitable feminine instruments in North America during the 19th Century in that they could be used to accompany ones singing and “required no facial exertions or body movements that interfered with the portrait of grace the lady musician was to emanate” (Tick, 1987, p. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club Since you’re reading this booklet, you’re obviously someone who likes to explore music more widely than the mainstream offerings of most other labels allow. Toccata Classics was set up explicitly to release recordings of music – from the Renaissance to the present day – that the microphones have been ignoring. How often have you heard a piece of music you didn’t know and wondered why it hadn’t been recorded before? Well, Toccata Classics aims to bring this kind of neglected treasure to the public waiting for the chance to hear it – from the major musical centres and from less-well-known cultures in northern and eastern Europe, from all the Americas, and from further afield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, Toccata Classics is exploring it. To link label and listener directly we run the Toccata Discovery Club, which brings its members substantial discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings, whether CDs or downloads, and also on the range of pioneering books on music published by its sister company, Toccata Press. A modest annual membership fee brings you, free on joining, two CDs, a Toccata Press book or a number of album downloads (so you are saving from the start) and opens up the entire Toccata Classics catalogue to you, both new recordings and existing releases as CDs or downloads, as you prefer. Frequent special offers bring further discounts. If you are interested in joining, please visit the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com and click on the ‘Discovery Club’ tab for more details. -

Tezfiatipnal "

tezfiatipnal" THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Borodin Quartet MIKHAIL KOPELMAN, Violinist DMITRI SHEBALIN, Violist ANDREI ABRAMENKOV, Violinist VALENTIN BERLINSKY, Cellist SUNDAY AFTERNOON, FEBRUARY 25, 1990, AT 4:00 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Quartet No. 2 in F major, Op. 92 .............................. PROKOFIEV Allegro sostenuto Adagio, poco piu animate, tempo 1 Allegro, andante molto, tempo 1 Quartet No. 3 (1984) .......................................... SCHNITTKE Andante Agitato Pesante INTERMISSION Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130, with Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 ...... BEETHOVEN Adagio, ma non troppo; allegro Presto Andante con moto, ma non troppo Alia danza tedesca: allegro assai Cavatina: adagio molto espressivo Finale: Grosse Fuge The Borodin Quartet is represented exclusively in North America by Mariedi Anders Artists Management, Inc., San Francisco. Cameras and recording devices are not allowed in the auditorium. Halls Cough Tablets, courtesy of Warner Lambert Company, are available in the lobby. Twenty-eighth Concert of the lllth Season Twenty-seventh Annual Chamber Arts Series PROGRAM NOTES Quartet No. 2 in F major, Op. 92 ........................ SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891-1953) Sergei Prokofiev, born in Sontsovka, in the Ekaterinoslav district of the Ukraine, began piano lessons at age three with his mother, who also encouraged him to compose. It soon became clear that the child was musically precocious, writing his first piano piece at age five and playing the easier Beethoven sonatas at age nine. He continued training in Moscow, studying piano with Reinhold Gliere, and in 1904, entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory where he studied harmony and counterpoint with Anatoly Lyadov, orchestration with Rimsky- Korsakov, and conducting with Alexander Tcherepnin. -

UC Santa Barbara Continuing Lecturer Natasha

CONTACT: Adriane Hill Marketing and Communications Manager (805) 893-3230 [email protected] music.ucsb.edu FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE / February 7, 2020 UC SANTA BARBARA CONTINUING LECTURER NATASHA KISLENKO TO PRESENT SOLO PIANO WORKS BY MOZART, CHOPIN, RACHMANINOFF, AND SCHNITTKE Internationally-renowned pianist to present solo piano works along with Lutosławski’s Variations on the GH theme by Paganini for two pianos with UC Santa Barbara Teaching Professor Sarah Gibson Santa Barbara, CA (February 7, 2020)—Natasha Kislenko, Continuing Lecturer of Keyboard at UC Santa Barbara, will present a solo piano recital on Friday, February 21, 2020 at 7:30 pm in Karl Geiringer Hall on the UC Santa Barbara campus. The program will include solo piano works by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Frédéric Chopin, Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Alfred Schnittke, plus a duo-piano work by Witold Lutosławski, featuring UC Santa Barbara Teaching Professor Sarah Gibson. Recognized by the Santa Barbara Independent for her “vividly expressive” interpretations and “virtuosity that left the audience exhilarated,” Kislenko offers unique concert programs and presentations to a worldwide community of music listeners. A prizewinner of several international piano competitions, she has extensively concertized in Russia, Germany, Italy, Spain, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Turkey, and across the Americas. A resident pianist of the Santa Barbara Symphony since 2010, she has been a featured soloist for the Shostakovich, Grieg, Clara Schumann, de Falla, and Mozart piano concerti, to great critical acclaim. Kislenko’s UC Santa Barbara program will open with Mozart’s Six Variations in F Major on “Salve tu, Domine” by G. Paisiello, K. 398. The theme of the work is taken from Mozart’s Italian contemporary Giovanni Paisiello’s opera, I filosofi immaginari (The Imaginary Philosophers), one of Paisiello’s most recognized opere buffe, written for the court of Catherine II of Russia. -

Color in Your Own Cello! Worksheet 1

Color in your own Cello! Worksheet 1 Circle the answer! This instrument is the: Violin Viola Cello Bass Which way is this instrument played? On the shoulder On the ground Is this instrument bigger or smaller than the violin? Bigger Smaller BONUS: In the video, Will said when musicians use their fingers to pluck the strings instead of using a bow, it is called: Piano Pizazz Pizzicato Potato Worksheet 2 ALL ABOUT THE CELLO Below are a Violin, Viola, Cello, and Bass. Circle the Cello! How did you know this was the Cello? In his video, Will talked about a smooth, connected style of playing when he played the melody in The Swan. What is this style with long, flowing notes called? When musicians pluck the strings on their instrument, does it make the sounds very short or very long? What is it called when musicians pluck the strings? What does the Cello sound like to you? How does that sound make you feel? Use the back of this sheet to write or draw what the sound of the Cello makes you think of! Worksheet 1 - ANSWERS Circle the answer! This instrument is the: Violin Viola Cello Bass Which way is this instrument played? On the shoulder On the ground Is this instrument bigger or smaller than the violin? Bigger Smaller BONUS: In the video, Will said when musicians use their fingers to pluck the strings instead of using a bow, it is called: Piano Pizazz Pizzicato Potato Worksheet 2 - ANSWERS ALL ABOUT THE CELLO Below are a violin, viola, cello, and bass. -

Nxta Cello Instructions STAND Open the Legs Wide for Stability, and Secure in Place with Thumb Screw Clamp

NXTa Cello Instructions STAND Open the legs wide for stability, and secure in place with thumb screw clamp. Mount the instrument to the stand using the large (5/16”) thumb screw at the top of the stand. Using the adjustment knobs, it is possible to adjust the height, angle, and tilt of the instrument. CONTROLS Knob 1 Volume – rotary control Knob 2 Tone – rotary control, clockwise for full treble, counter-clockwise to cut treble. Dual Output Mode – push-pull control, in for Passive Mode, out for Active Mode. Active Mode – Using the supplied charger, connect the NXTa to any AC outlet for 60 seconds. This will fuel the capacitor-powered active circuit for up to 16 hours of performance time. The instrument can then be plugged straight into any low or high impedance device, no direct box necessary. Passive Mode* – The NXTa can be played in this mode with an amplifier with an impedance of 1 meg ohm or greater (3-10 meg ohm recommended) or with a direct box. Switch Arco/Pizzicato Mode selection, toggle up for Arco, toggle down for Pizzicato The design of the Polar™ Pickup System enables you to choose between two distinct attack and decay characteristics: Arco Mode is for massive attack and relatively fast decay, optimal for bowed and percussive plucked sound. Pizzicato Mode is for a smooth attack and long decay, optimal for plucked, sustained sound. This mode is not recommended for bowing. Note that the Polar™ pickup allows the player to control attack and decay parameters. Pizzicato Mode is for a smoother attack and longer decay when plucked. -

Dissertation First Pages

Dissertation in Music Performance by Joachim C. Angster A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Dissertation Committee: Assistant Professor Caroline Coade, Co-Chair Professor David Halen, Co-Chair Professor Colleen Conway Associate Professor Max Dimoff Professor Daniel Herwitz Joachim C. Angster [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2563-2819 © Joachim C. Angster 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to members of my Doctoral Committee and to my teacher Professor Caroline Coade in particular, for making me a better musician. I also would like to give special thanks to my collaborators Arianna Dotto, Meridian Prall, Ji-Hyang Gwak, Taylor Flowers, and Nathaniel Pierce. Finally, I am grateful for the continuous support of my parents, and for the invaluable help of Anna Herklotz and Gabriele Dotto. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv FIRST DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 1 Program Notes 2 SECOND DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 18 Program Notes 19 THIRD DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 27 Program Notes 28 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 iii ABSTRACT This dissertation pertains to three viola recitals, which were respectively performed on 2 October 2019, 20 January 2020, and 9 March 2020. Each recital program embraced a specific theme involving little-performed works as well as staples from the viola repertoire, and covered a wide range of different musical styles. The first recital, performed with violinist Arianna Dotto, focused on violin and viola duo repertoire. Two pieces in the Classical and early Romantic styles by W. A. Mozart and L. -

Download Booklet

Charming Cello BEST LOVED GABRIEL SCHWABE © HNH International Ltd 8.578173 classical cello music Charming Cello the 20th century. His Sérénade espagnole decisive influence on Stravinsky, starting a Best loved classical cello music uses a harp and plucked strings in its substantial neo-Classical period in his writing. A timeless collection of cello music by some of the world’s greatest composers – orchestration, evoking Spain in what might including Beethoven, Haydn, Schubert, Vivaldi and others. have been a recollection of Glazunov’s visit 16 Goodall: And the Bridge is Love (excerpt) to that country in 1884. ‘And the Bridge is Love’ is a quotation from Thornton Wilder’s novel The Bridge of 1 6 Johann Sebastian BACH (1685–1750) Franz Joseph HAYDN (1732–1809) 14 Ravel: Pièce en forme de habanera San Luis Rey which won the Pulitzer Prize Bach: Cello Suite No. 1 in G major, 2:29 Cello Concerto in C major, 9:03 (arr. P. Bazelaire) in 1928. It tells the story of the collapse BWV 1007 – I. Prelude Hob.VIIb:1 – I. Moderato Swiss by paternal ancestry and Basque in 1714 of ‘the finest bridge in all Peru’, Csaba Onczay (8.550677) Maria Kliegel • Cologne Chamber Orchestra through his mother, Maurice Ravel combined killing five people, and is a parable of the Helmut Müller-Brühl (8.555041) 2 Camille SAINT-SAËNS (1835–1921) his two lineages in a synthesis that became struggle to find meaning in chance and in Le Carnaval des animaux – 3:07 7 Robert SCHUMANN (1810–1856) quintessentially French. His Habanera, inexplicable tragedy. -

Molly Parson-Gurr Recital Programme 25 Oct 2016

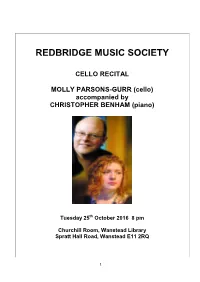

REDBRIDGE MUSIC SOCIETY CELLO RECITAL MOLLY PARSONS-GURR (cello) accompanied by CHRISTOPHER BENHAM (piano) Tuesday 25th October 2016 8 pm Churchill Room, Wanstead Library Spratt Hall Road, Wanstead E11 2RQ 1 PROGRAMME ‘Arioso’ for cello and piano J S Bach (1685 – 1750) Suite No. 1 in G major for solo cello BWV 1007 J S Bach (1685 – 1750) i Prelude ii Allemande iii Courante iv Sarabande v Minuets 1 & 2 vi Gigue Drei Fantasiestücke for cello and piano Op. 73 Robert Schumann (1810 - 1856) i Zart und mit Ausdruck (Tender and with expression) ii Lebhaft, leicht (Lively, light) iii Rasch und mit Feuer (Quick and with fire) INTERVAL Sonata in G minor for Cello and Piano Op 19 Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873 – 1943) i Lento – Allegro moderato ii Allegro scherzando iii Andante iv Allegro mosso PROGRAMME NOTES J S Bach: Arioso for cello and piano & Suite No. 1 in G major for solo cello BWV 1007 The ‘arioso’ you will hear at this evening’s recital is an arrangement for cello and piano of the sinfonia which opens Bach’s church Cantata "Ich steh`mit einem Fuss im Grabe" (“I am standing with one foot in the grave”) BWV 156 first performed in Leipzig in 1729. The original sinfonia was scored for oboe, strings and continuo and was most likely derived from an early F major oboe concerto of Bach’s; it appears also as the middle movement (largo) of Bach’s Harpsichord Concerto No.5 in F minor BWV 1056. There have been many arrangements of the ‘arioso’ including those for trumpet and piano, violin and piano, solo guitar and also for full orchestra (the latter arr. -

Schnittke CD Catalogue

Ivahskin-Schnittke Archive Compact Discs Archive Year of CD Title Schnittke pieces included Performers Label Recording Recording/ Number on CD Number release 1 String trios - Schnittke, String Trio Krysa, O: Kuchar, T; - - - Penderecki, Gubaidulina Ivashkin, A. 2 Webber, Schumman, Sonata for Violin No.2 Kremer, G; Gavrilov, A; Muti, Olympia 501079 1982/1979 Hindesmith, Schnittke (Quasi una sonata) R. Symponic Prelude Schnittke - Symphonic Norrkoping Symphony (1993)/Symphony no.8 3 prelude, Symphony no. 8, Orchestra (Lu Jia - BIS BIS-CD-1217 2005 (1994)/ For Liverpool For Liverpool Conductor) (1994) Schnittke - Minnesang, Minnesang, Concerto for 4 Concerto for mixed choir mixed choir Danish Choir - - - Schnittke - Lux Aeterna Lux Aeterna (Requiem of (Requiem of 5 reconciliation) Krakow Chamber Choir - - 1995 reconciliation) 6 [number not in use] 7 [number not in use] 8 Rastakov, A (Composer) Schnittke: Ritual - (K)ein Ritual/ (K)ein sommernachtstraum - Sommernachtstraum/ Malmo SymphonyOrchestra 9 Passacaglia - Seid nuchten Passacaglia/ Seid nuchtern BIS BIS-CD-437 1989 und wachet und wachtet The State Chamber Choir of the USSR (Dof-Fonskaya, E - 10 Schnittke - Concerto for Concerto for choir in four Soprano; Polyanky, V - Arteton VICC-51 1991 choir in four movements movements Conductor) BBC Symphony Orchestra Alfred Schnittke - Symphony no.2 'St (conducted by Carlton 15656 1997 Symphony no. 2 'St Florian'/ Pas de quatre Rozhdestvensky, G) & BBC Classics 91962 11 Florian' Symphony Chorus (conducted by Cleobury, S) 12 [number not in use] 13 [number not in use] Ivahskin-Schnittke Archive Compact Discs Three madrigals (Sur une Soloists Ensemble of the Denisov, Schnittke, Mobile 14 etoile, Entfernung, Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra MFCD 869 1983 Gubaidulina, Mansurian Fidelity Reflection) Sound Lab The USSR Ministry of Culture Orchestra 15 A Schnittke - Symphony Symphony no.1 Melodiya SUCD 10- 1990/1987 (conducted by no.