Publication Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Useful Are Episcopal Ordination Lists As a Source for Medieval English Monastic History?

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. , No. , July . © Cambridge University Press doi:./S How Useful are Episcopal Ordination Lists as a Source for Medieval English Monastic History? by DAVID E. THORNTON Bilkent University, Ankara E-mail: [email protected] This article evaluates ordination lists preserved in bishops’ registers from late medieval England as evidence for the monastic orders, with special reference to religious houses in the diocese of Worcester, from to . By comparing almost , ordination records collected from registers from Worcester and neighbouring dioceses with ‘conven- tual’ lists, it is concluded that over per cent of monks and canons are not named in the extant ordination lists. Over half of these omissions are arguably due to structural gaps in the surviving ordination lists, but other, non-structural factors may also have contributed. ith the dispersal and destruction of the archives of religious houses following their dissolution in the late s, many docu- W ments that would otherwise facilitate the prosopographical study of the monastic orders in late medieval England and Wales have been irre- trievably lost. Surviving sources such as the profession and obituary lists from Christ Church Canterbury and the records of admissions in the BL = British Library, London; Bodl. Lib. = Bodleian Library, Oxford; BRUO = A. B. Emden, A biographical register of the University of Oxford to A.D. , Oxford –; CAP = Collectanea Anglo-Premonstratensia, London ; DKR = Annual report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records, London –; FOR = Faculty Office Register, –, ed. D. S. Chambers, Oxford ; GCL = Gloucester Cathedral Library; LP = J. S. Brewer and others, Letters and papers, foreign and domestic, of the reign of Henry VIII, London –; LPL = Lambeth Palace Library, London; MA = W. -

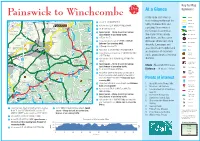

Painswick to Winchcombe Cycle Route

Great Comberton A4184 Elmley Castle B4035 Netherton B4632 B4081 Hinton on the Green Kersoe A38 CHIPPING CAMPDEN A46(T) Aston Somerville Uckinghall Broadway Ashton under Hill Kemerton A438 (T) M50 B4081 Wormington B4479 Laverton B4080 Beckford Blockley Ashchurch B4078 for Tewkesbury Bushley B4079 Great Washbourne Stanton A38 A38 Key to Map A417 TEWKESBURY A438 Alderton Snowshill Day A438 Bourton-on-the-Hill Symbols: B4079 A44 At a Glance M5 Teddington B4632 4 Stanway M50 B4208 Dymock Painswick to WinchcombeA424 Linkend Oxenton Didbrook A435 PH A hilly route from start to A Road Dixton Gretton Cutsdean Hailes B Road Kempley Deerhurst PH finish taking you through the Corse Ford 6 At fork TL SP BRIMPSFIELD. B4213 B4211 B4213 PH Gotherington Minor Road Tredington WINCHCOMBE Farmcote rolling Cotswold hills and Tirley PH 7 At T junctionB4077 TL SP BIRDLIP/CHELTENHAM. Botloe’s Green Apperley 6 7 8 9 10 Condicote Motorway Bishop’s Cleeve PH Several capturing the essence of Temple8 GuitingTR SP CIRENCESTER. Hardwicke 22 Lower Apperley Built-up Area Upleadon Haseld Coombe Hill the Cotswold countryside. Kineton9 Speed aware – Steep descent on narrow B4221 River Severn Orchard Nook PH Roundabouts A417 Gorsley A417 21 lane. Beware of oncoming traffic. The route follows mainly Newent A436 Kilcot A4091 Southam Barton Hartpury Ashleworth Boddington 10 At T junction TL. Lower Swell quiet lanes, and has some Railway Stations B4224 PH Guiting Power PH Charlton Abbots PH11 Cross over A 435 road SP UPPER COBERLEY. strenuous climbs and steep B4216 Prestbury Railway Lines Highleadon Extreme Care crossing A435. Aston Crews Staverton Hawling PH Upper Slaughter descents. -

Journal Issue 3, May 2013

Stonehouse History Group Journal Issue 3 May 2013 ISSN 2050-0858 Published by Stonehouse History Group www.stonehousehistorygroup.org.uk [email protected] May 2013 ©Stonehouse History Group Front cover sketch “The Spa Inn c.1930” ©Darrell Webb. We have made every effort to obtain permission from the copyright owners to reproduce their photographs in this journal. Modern photographs are copyright Stonehouse History Group unless otherwise stated. No copies may be made of any photographs in this issue without the permission of Stonehouse History Group (SHG). Editorial Team Vicki Walker - Co-ordinating editor Jim Dickson - Production editor Shirley Dicker Janet Hudson John Peters Darrell Webb Why not become a member of our group? We aim to promote interest in the local history of Stonehouse. We research and store information about all aspects of the town’s history and have a large collection of photographs old and new. We make this available to the public via our website and through our regular meetings. We provide a programme of talks and events on a wide range of historical topics. We hold meetings on the second Wednesday of each month, usually in the Town Hall at 7:30pm. £1 members; £2 visitors; annual membership £5 2 Stonehouse History Group Journal Issue 3, May 2013 Contents Obituary of Les Pugh 4 Welcome to our third issue 5 Oldends: what’s in an ‘s’? by Janet Hudson 6 Spa Inn, Oldends Lane by Janet Hudson, Vicki Walker and Shirley Dicker 12 Oldends Hall by Janet Hudson 14 Stonehouse place names by Darrell Webb 20 Charles -

7-Night Cotswolds Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Cotswolds Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Cotswolds & England Trip code: BNBOB-7 1 & 2 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Gentle hills, picture-postcard villages and tempting tea shops make this quintessentially English countryside perfect for walking. On our Guided Walking holidays you'll discover glorious golden stone villages with thatched cottages, mansion houses, pastoral countryside and quiet country lanes. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 5 days guided walking and 1 free day • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point • Choice of up to three guided walks each walking day • The services of HF Holidays Walking Leaders www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Explore the beautiful countryside and rich history of the Cotswolds • Gentle hills, picture-postcard villages and tempting tea shops make this quintessentially English countryside perfect for walking • Let your leader bring the picturesque countryside and history of the Cotswolds to life • In the evenings relax and enjoy the period features and historic interest of Harrington House ITINERARY Version 1 Day 1: Arrival Day You're welcome to check in from 4pm onwards. Enjoy a complimentary Afternoon Tea on arrival. Day 2: South Along The Windrush Valley Option 1 - The Quarry Lakes And Salmonsbury Camp Distance: 6½ miles (10.5km) Ascent: 400 feet (120m) In Summary: A circular walk starts out along the Monarch’s Way reaching the village of Clapton-on-the-Hill. We return along the Windrush valley back to Bourton. -

Pathology Van Route Information

Cotswold Early Location Location Depart Comments Start CGH 1000 Depart 1030 Depart 1040 if not (1005) going to Witney Windrush Health Centre Witney 1100 Lechlade Surgery 1125 Hilary Cottage Surgery, Fairford 1137 Westwood Surgery Northleach 1205 Moore Health Centre BOW 1218 George Moore Clinic BOW 1223 Well Lane Surgery Stow 1237 North Cotswolds Hospital MIM 1247 White House Surgery MIM 1252 Mann Cottage MIM 1255 Chipping Campden Surgery 1315 Barn Close MP Broadway 1330 Arrive CGH 1405 Finish 1415 Cotswold Late Location Location Depart Comments Start Time 1345 Depart CGH 1400 Abbey Medical Practice Evesham 1440 Merstow Green 1445 Riverside Surgery 1455 CGH 1530-1540 Westwood Surgery Northleach 1620 Moore Health Centre BOW 1635 Well Lane Surgery Stow 1655 North Cotswolds Hospital MIM 1705 White House Surgery M-in-M 1710 Mann Cottage MIM 1715 Chipping Campden Surgery 1735 Barn Close MP Broadway 1750 Winchcombe MP 1805 Cleeve Hill Nursing Home Winchcombe 1815 Arrive CGH 1830 Finish 1845 CONTROLLED DOCUMENT PHOTOCOPYING PROHIBITED Visor Route Information- GS DR 2016 Version: 3.30 Issued: 20th February 2019 Cirencester Early Location Location Depart Comments Start 1015 CGH – Pathology Reception 1030 Cirencester Hospital 1100-1115 Collect post & sort for GPs Tetbury Hospital 1145 Tetbury Surgery (Romney House) 1155 Cirencester Hospital 1220 Phoenix Surgery 1230 1,The Avenue, Cirencester 1240 1,St Peter's Rd., Cirencester 1250 The Park Surgery 1300 Rendcomb Surgery 1315 Sixways Surgery 1335 Arrive CGH 1345 Finish 1400 Cirencester Late Location -

The Five Valleys & Severn Vale

The Five valleys & severn vale... stay a night or two in the Five valleys around stroud. spend 48 hours exploring the Cotswold towns of stroud and nailsworth, and around Berkeley in the severn vale. But don’t feel limited to just 48 hours; we’d love you to stay longer. day 1 where To sTay Spend the day exploring the Five Choose from a selection of Valleys. Start with the bohemian accommodation around the Stroud canal-side town, Stroud , where valleys including the boutique-style cafés and independent shops are Bear of Rodborough on Rodborough a plenty. Don’t miss the fabulous Common, luxurious The Painswick Farmers’ Market , filling the streets (in the town of the same name), every Saturday morning. Take a a range of bed & breakfasts or stroll along the canal towpath country inns. or up to the beautiful commons. Head on to the hilltop town of hidden gems Painswick to wander the pretty Explore the woollen mills that streets or visit its spectacular brought so much wealth to the churchyard – a photographer’s Five Valleys (open to visitors on dream. The neighbouring village of select days by the Stroudwater Slad is the setting of famous novel, Textiles Trust ). Pack a picnic Cider with Rosie . Alternatively, visit from Stroud Farmers’ Market and artistic Nailsworth , renowned for head up to beautiful Rodborough its award-winning eateries, lovely or Selsley Commons . Explore the shops and celebrated bakery. unique Rococo Garden in Painswick (famous for its winter snowdrops). Stroud is located in the south Cotswolds, Pop in for a pint at Laurie Lee’s encircled by five beautiful valleys: The Frome favourite pub, The Woolpack (known as Golden Valley), Nailsworth, in Slad. -

Tewkesbury Community Connector

How much will it cost? 630 £1.50 adult return and £1.00 child up to 16 return on Tewkesbury Community Connector. £1.80 adult return on service 540 to Evesham. Tewkesbury £3.20 adult return on service D to Cheltenham. Please note: through ticketing unavailable at present. Fares to be paid to the connecting service driver and not Community to Tewkesbury Community Connector drivers. Contact details Holders of concessionary bus passes can travel free. To book your journey on Tewkesbury Connector Community Connector and for more How to book information please contact Third Sector To book your journey, simply call Third Sector Services Services on 0845 680 5029 on 0845 680 5029 between 8.00am and 4.00pm on the day before you travel. The booking line is open Monday Third Sector Services, Sandford Park Offices to Friday. You can also tell the Tewkesbury Community College Road, Cheltenham, GL53 7HX Connector driver when you next want to travel. www.thirdsectorservices.org.uk Please book by Friday of the previous week if you require transport on Saturday or Monday. When you book you will need to specify the day required, which village to pick you up from and where you intend to travel. You will be advised of the pick up place and time. Please note: the vehicle may arrive up to 10 minutes before or 10 minutes after the agreed time. Introducing a new community transport service for Tewkesbury Borough Operated by Third Sector Services in partnership with Gloucestershire County Council Further information Some journeys on service 606 will now serve Alderton and Gretton. -

Download Walk

Viaduct St. Andrew’s Church Toddington Cricket New Pavilion B4077 T o w n Stanway House St. Peter’s Church GWR Stanway Station Stanway Watermill Winchcombe Walkers are Welcome y a W e www.winchcombewelcomeswalkers.com n B4078 r u o b Is 0 0.25 0.5 mile WINCHCOMBE 0 0.5 km R i v e r St. George’s Isb Church ou Bus & Walk 14 Cleeve Hill to Winchcombe r n e Didbrook Wood Golf Club’. With the club house on your Bus Stagecoach W service out Stanway right, cross a cattle grid onto Cleeve and walk back Common and turn immediately left. The walk starts at the top of Cleeve Keep ahead on the track, pass through Hill and slowly descends back into one gate to reach a secondChurch gate A. Here Pass Corndean Hall, down to your left Winchcombe through a varied pass through and bear right downhill Royaluntil reaching a T-junction D. Gretton Oak landscape. on the track, taking a left fork in about B4362 Hailes Hailes Church At a road junction, take the footpath on Church Distance: 4 miles/ 6.4 km Stanley250 metres to reach a gate. Pass under Hailes Pontlarge the left (Cotswold Way) through the gate Wood overhanging trees to a small stabling area. Hailes River Isbourne Abbey Duration 2 hours (walking) Keep to the footpath and pass through into a field and walk downhillGreet to a gate. Prescott Go through and turn right ontoPottery a tarmac Hayles ay Fruit Farm ay Difficulty: Moderate gates and between buildings, skirtingCups Hill W W Gotherington Stanley old ld drive, passing a cricket ground on your w o Winchcombe ts w Halt Station Hill Wood o s Postlip Hall to your left behind a high C t Climb GWSR Station o Start/finish: Back Lane car park, stone wall. -

Gloucestershire Village & Community Agents

Helping older people in Gloucestershire feel more independent, secure, and have a better quality of life May 2014 Gloucestershire Village & Community Agents Managed by GRCC Jointly funded by Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group www.villageagents.org.uk Helping older people in Gloucestershire feel more independent, secure, and have a better quality of life Gloucestershire Village & Community Agents Managed by GRCC Jointly funded by Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group Gloucestershire Village and Key objectives: To give older people easy Community Agents is aimed 3 access to a wide range of primarily at the over 50s but also To help older people in information that will enable them offers assistance to vulnerable 1 Gloucestershire feel more to make informed choices about people in the county. independent, secure, cared for, their present and future needs. and have a better quality of life. The agents provide information To engage older people to To promote local services and support to help people stay 4 enable them to influence and groups, enabling the independent, expand their social 2 future planning and provision. Agent to provide a client with a activities, gain access to a wide community-based solution To provide support to range of services and keep where appropriate. people over the age of 18 involved with their local 5 who are affected by cancer. communities. Partner agencies ² Gloucestershire County Council’s Adult Social Care Helpdesk ² Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group ² Gloucestershire Rural Community -

Gloucestershire Parish Map

Gloucestershire Parish Map MapKey NAME DISTRICT MapKey NAME DISTRICT MapKey NAME DISTRICT 1 Charlton Kings CP Cheltenham 91 Sevenhampton CP Cotswold 181 Frocester CP Stroud 2 Leckhampton CP Cheltenham 92 Sezincote CP Cotswold 182 Ham and Stone CP Stroud 3 Prestbury CP Cheltenham 93 Sherborne CP Cotswold 183 Hamfallow CP Stroud 4 Swindon CP Cheltenham 94 Shipton CP Cotswold 184 Hardwicke CP Stroud 5 Up Hatherley CP Cheltenham 95 Shipton Moyne CP Cotswold 185 Harescombe CP Stroud 6 Adlestrop CP Cotswold 96 Siddington CP Cotswold 186 Haresfield CP Stroud 7 Aldsworth CP Cotswold 97 Somerford Keynes CP Cotswold 187 Hillesley and Tresham CP Stroud 112 75 8 Ampney Crucis CP Cotswold 98 South Cerney CP Cotswold 188 Hinton CP Stroud 9 Ampney St. Mary CP Cotswold 99 Southrop CP Cotswold 189 Horsley CP Stroud 10 Ampney St. Peter CP Cotswold 100 Stow-on-the-Wold CP Cotswold 190 King's Stanley CP Stroud 13 11 Andoversford CP Cotswold 101 Swell CP Cotswold 191 Kingswood CP Stroud 12 Ashley CP Cotswold 102 Syde CP Cotswold 192 Leonard Stanley CP Stroud 13 Aston Subedge CP Cotswold 103 Temple Guiting CP Cotswold 193 Longney and Epney CP Stroud 89 111 53 14 Avening CP Cotswold 104 Tetbury CP Cotswold 194 Minchinhampton CP Stroud 116 15 Bagendon CP Cotswold 105 Tetbury Upton CP Cotswold 195 Miserden CP Stroud 16 Barnsley CP Cotswold 106 Todenham CP Cotswold 196 Moreton Valence CP Stroud 17 Barrington CP Cotswold 107 Turkdean CP Cotswold 197 Nailsworth CP Stroud 31 18 Batsford CP Cotswold 108 Upper Rissington CP Cotswold 198 North Nibley CP Stroud 19 Baunton -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'. -

Education in Medieval Bristol and Gloucestershire by N

From the Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Education in Medieval Bristol and Gloucestershire by N. Orme 2004, Vol. 122, 9-27 © The Society and the Author(s) Trans. Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 122 (2004), 9–27 Education in Medieval Bristol and Gloucestershire By NICHOLAS ORME Presidential Address delivered at Clifton Cathedral, Bristol, 27 March 2004 Going to school in the middle ages may seem like an oxymoron. Did anyone go? And if they went, was it to what we would recognise as a school, or merely a place where terrified children sat on the floor mumbling information by heart, while a teacher brandished a birch in their faces and periodically on their bottoms? My answer would be that there were indeed schools, that they operated in logical, imaginative, and effective ways, and that many people attended them — not only future clergy but laity too. Medieval Bristol and Gloucestershire constituted only a fortieth part of medieval England but they are admirably representative of the kingdom as a whole in the kinds of schools they had and in the history of these schools. I first published a study of them in 1976, and it is welcome to have this opportunity of looking at them afresh nearly thirty years later.1 During this period great advances have been made in understanding the nature of school education in medieval England. The Bristol and Gloucestershire evidence can be explained and understood more fully in the light of this understanding than was possible in the 1970s.2 When did schooling begin in our county? It may have existed in Roman times in places like Cirencester and Gloucester, but it has left no record.