Master of the Slow Surprise by KYLE GANN TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 1999 at 4 A.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{Download PDF} Goodbye 20Th Century: a Biography of Sonic

GOODBYE 20TH CENTURY: A BIOGRAPHY OF SONIC YOUTH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Browne | 464 pages | 02 Jun 2009 | The Perseus Books Group | 9780306816031 | English | Cambridge, MA, United States SYR4: Goodbye 20th Century - Wikipedia He was also in the alternative rock band Sonic Youth from until their breakup, mainly on bass but occasionally playing guitar. It was the band's first album following the departure of multi-instrumentalist Jim O'Rourke, who had joined as a fifth member in It also completed Sonic Youth's contract with Geffen, which released the band's previous eight records. The discography of American rock band Sonic Youth comprises 15 studio albums, seven extended plays, three compilation albums, seven video releases, 21 singles, 46 music videos, nine releases in the Sonic Youth Recordings series, eight official bootlegs, and contributions to 16 soundtracks and other compilations. It was released in on DGC. The song was dedicated to the band's friend Joe Cole, who was killed by a gunman in The lyrics were written by Thurston Moore. It featured songs from the album Sister. It was released on vinyl in , with a CD release in Apparently, the actual tape of the live recording was sped up to fit vinyl, but was not slowed down again for the CD release. It was the eighth release in the SYR series. It was released on July 28, The album was recorded on July 1, at the Roskilde Festival. The album title is in Danish and means "Other sides of Sonic Youth". For this album, the band sought to expand upon its trademark alternating guitar arrangements and the layered sound of their previous album Daydream Nation The band's songwriting on Goo is more topical than past works, exploring themes of female empowerment and pop culture. -

THE D.A.P. INTERNATIONAL CATALOGUE SPRING 2021 MATTHEW WONG: MOBY-DICK POSTCARDS ISBN 9781949172430 ISBN 9781949172508 Hbk, U.S

THE D.A.P. INTERNATIONAL CATALOGUE SPRING 2021 MATTHEW WONG: MOBY-DICK POSTCARDS ISBN 9781949172430 ISBN 9781949172508 Hbk, U.S. $35.00 GBP £30.00 Clth, U.S. $35.00 GBP £30.00 Karma Books, New York Karma Books, New York Territory: WORLD Territory: WORLD ON EDWARD HICKS THE MAYOR OF LEIPZIG Installation shot from the exhibition Pastel, curated by Nicolas Party. Photograph by Hilary Pecis. ISBN 9781646570065 ISBN 9781949172478 From Pastel, published by The FLAG Art Foundation, New York. See page 124. Hbk, U.S. $35.00 GBP £30.00 Recent Releases Hbk, U.S. $20.00 GBP £17.50 Lucia|Marquand Karma Books, New York Territory: WORLD from D.A.P. Territory: WORLD Featured Releases 2 Spring Highlights 36 Photography 38 CATALOG EDITOR Thomas Evans Art 42 Design 59 DESIGNER Architecture 62 Martha Ormiston COPYWRITING Specialty Books 66 Arthur Cañedo, Thomas Evans, Emilia Copeland Titus, Madeline Weisburg Art 68 IMAGE PRODUCTION Photography 78 Joey Gonnella PRINTING Backlist Highlights 79 Short Run Press Limited TANTRA SONG ISBN 9780979956270 DANNY LYON: Hbk, U.S. $39.95 GBP £35.00 AMERICAN BLOOD Siglio ISBN 9781949172454 FRONT COVER: Emil Bisttram, Creative Forces, 1936. Oil on canvas, 36 x 27". Private collection, Courtesy Aaron Payne Fine Art, Santa Fe. From Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group, published by DelMonico Books/Crocker Art Museum. See page 4. BACK COVER: Flores & Prats, cross-section through lightwells, Cultural Centre Casal Balaguer, Palma de Mallorca. Territory: WORLD Hbk, U.S. $35.00 GBP £30.00 From Thought by Hand: The Architecture of Flores & Prats, published by Arquine. -

Echofluxx 11

Contributors to ECHOFLUXX 12. – 16. Červenec 2011, /July 12th – 16th, 2011 via Kickstarter.com Trafačka Arena, Praha 9, Česká republika/Czech Republic Shining Star of Echofluxx Michael Karman Bright Light of Echofluxx ECHOFLUXX Eliane G. Burnett Festival experimentální hudby a nových médií Experimental music and new media festival Angel of Echofluxx Carol Senn Ruffin Denise Senn Benefactor of Echofluxx Úterý/Tuesday, 19.00 David Drexler Phill Niblock (US), William Estes Katherine Liberovskaya (CA) and Al Margolis (US) Mike Wood Středa/Wednesday, 19.00 Stanislav Abrahám (CZ), Patron of Echofluxx Michal Rataj (CZ) and Ivan Boreš (CZ), Camilla Hoitenga Peter Szely (AT) Stephan Moore Mike Martin Čtvrtek/Thursday, 19.00 Chris Frye Martin Janíček (CZ) and Petr Ferenc (CZ), Martin Blažíček (CZ) and Krystof Topolski (PL) Friends of Echofluxx Petra Vlachynská Pátek/Friday, 19.00 Anja Kaufmann (CH) and Frances Sanders (UK), Marcia A. Mueller George Cremaschi (US), Bonnie Miksch Hana Železná (CZ) Josh Payne Mary Wright Sobota/Saturday, 19.00 Nick Senn Petra Dubach and Mario van Horrik (NL), Christian Andrew Senn Hearn Gadbois (US/CZ) 8 1 BIOGRAPHIES Phill Niblock (US) is a New York-based minimalist composer and multi-media musician Petra Dubach & Mario van Horrik (NL) have been working together artistically since 1994. and director of Experimental Intermedia, a foundation born in the flames of 1968's The starting point for their work is the idea that movement and sound are identical and barricade-hopping. He has been a maverick presence on the fringes of the avant garde without movement (vibration) nothing can be heard. This idea is worked in every thinkable ever since. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Vinylnews 03-04-2020 Bis 05-06-2020.Xlsx

Artist Title Units Media Genre Release ABOMINATION FINAL WAR -COLOURED- 1 LP STM 17.04.2020 ABRAMIS BRAMA SMAKAR SONDAG -REISSUE- 2 LP HR. 29.05.2020 ABSYNTHE MINDED RIDDLE OF THE.. -LP+CD- 2 LP POP 08.05.2020 ABWARTS COMPUTERSTAAT / AMOK KOMA 1 LP PUN 15.05.2020 ABYSMAL DAWN PHYLOGENESIS -COLOURED- 1 LP STM 17.04.2020 ABYSMAL DAWN PHYLOGENESIS -GATEFOLD- 1 LP STM 17.04.2020 AC/DC WE SALUTE YOU -COLOURED- 1 LP ROC 10.04.2020 ACACIA STRAIN IT COMES IN.. -GATEFOLD- 1 LP HC. 10.04.2020 ACARASH DESCEND TO PURITY 1 LP HM. 29.05.2020 ACCEPT STALINGRAD-DELUXE/LTD/HQ- 2 LP HM. 29.05.2020 ACDA & DE MUNNIK GROETEN UIT.. -COLOURED- 1 LP POP 05.06.2020 ACHERONTAS PSYCHICDEATH - SHATTERING 2 LP BLM 01.05.2020 ACHERONTAS PSYCHICDEATH.. -COLOURED- 2 LP BLM 01.05.2020 ACHT EIMER HUHNERHERZEN ALBUM 1 LP PUN 27.04.2020 ACID BABY JESUS 7-SELECTED OUTTAKES -EP- 1 12in GAR 15.05.2020 ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE REVERSE OF.. -LTD- 1 LP ROC 24.04.2020 ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE & THE CHOSEN STAR CHILD`S.. 1 LP ROC 24.04.2020 ACID TONGUE BULLIES 1 LP GAR 08.05.2020 ACXDC SATAN IS KING 1 LP PUN 15.05.2020 ADDY ECLIPSE -DOWNLOAD- 1 LP ROC 01.05.2020 ADULT PERCEPTION IS/AS/OF.. 1 LP ELE 10.04.2020 ADULT PERCEPTION.. -COLOURED- 1 LP ELE 10.04.2020 AESMAH WALKING OFF THE HORIZON 2 LP ROC 24.04.2020 AGATHOCLES & WEEDEOUS HOL SELF.. -COLOURED- 1 LP M_A 22.05.2020 AGENT ORANGE LIVING IN DARKNESS -RSD- 1 LP PUN 18.04.2020 AGENTS OF TIME MUSIC MADE PARADISE 1 12in ELE 10.04.2020 AIRBORNE TOXIC EVENT HOLLYWOOD PARK -HQ- 2 LP ROC 08.05.2020 AIRSTREAM FUTURES LE FEU ET LE SABLE 1 LP ROC 24.04.2020 ALBINI, STEVE & ALISON CH MUSIC FROM THE FILM. -

The Golden Age of Non-Idiomatic Improvisation

The Golden Age of Non-Idiomatic Improvisation FYS 129 David Keffer, Professor Dept. of Materials Science & Engineering The University of Tennessee Knoxville, TN 37996-2100 [email protected] http: //cl ausi us.engr.u tk.e du / Various Quotes These slides contain a collection of some of the quotes largely from the musicians that are studied during the course. The idea is to present “musicians in their own words”. Thurston Moore American guitarist and vocalist (July 25, 1958—) Background on Sonic Youth Thurston Moore was a guitarist and vocalist for Sonic Youth. Sonic Youth was an American alternative rock band from New York City, formed in 1981. Their lineup largely consisted of Thurston Moore (guitar and vocals), Kim Gordon (bass guitar, vocals, and guitar), Lee Ranaldo (guitar and vocals), Steve Shelley (drums). In their early career, Sonic Youth was associated with the no wave art and music scene in New York City. Part of the first wave of American noise rock groups, the band carried out their interpretation of the hardcore punk ethos throughout the evolving American underground that focused more on the DIY ethic of the genre rather than its specific sound. As a result, some consider Sonic Youth as pivotal in the rise of the alternative rock and indie rock movementThbdts. The band exper ience d success an ditild critical acc lithhtlaim throughout their existence, continuing into the new millennium, including signing to major label DGC in 1990, and headlining the 1995 Lollapalooza festival. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonic_youth Moore Quotes Q: What led Sonic Youth to do a project like Goodbye 20th Century? Moore: It was definitely a universe or world that we were aware of. -

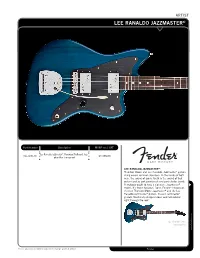

Lee Ranaldo Jazzmaster®

ARTIST LEE RANALDO JAZZMASTER® Part Number Description MSRP excl. VAT Lee Ranaldo Jazzmaster®, Rosewood Fretboard, Sap- 011-5100-727 phire Blue Transparent €1,895.00 LEE RANALDO JAZZMASTER®: Thurston Moore and Lee Ranaldo. Jazzmaster® guitars slung across seminal shoulders. In the hands of both men, the sound of Sonic Youth is the sound of that guitar used as part paintbrush and part cluster bomb. If anybody ought to have a signature Jazzmaster® model, it’s those two guys. Done. Fender® introduces the new Thurston Moore Jazzmaster® and the Lee Ranaldo Jazzmaster® guitars. Classic Jazzmaster® gestalt, Youth-fully stripped down and hot rodded right through the roof. 727 (Saphire Blue Transparent) www.fender.com Prices and specifications subject to change without notice. Fender ARTIST LEE RANALDO JAZZMASTER® COLORS: (727) parent Saphire Blue Trans- SPECIFICATIONS: Body Alder Finish Satin Nitrocellulose Lacquer Finish Neck Maple w/ Satin Black Painted Headstock, “C” Shape Fingerboard Rosewood, 7.25” Radius (184 mm) Frets 21, Vintage Style Scale Length 25.5” Nut Width: 1.650” Hardware Chrome Tuning Keys Fender® Vintage Style Tuning Machines Bridge American Vintage Jazzmaster® Tremolo with Mustang® Bridge and Tremolo Lock Button. Pickguard Anodized Black Pickups 2 New Fender® Wide Range Humbucking Pickups Re- Voiced to Original Vintage Spec, (Neck/Bridge) Pickup Switching 3-Position Toggle: Position 1. Bridge Pickup Position 2. Bridge and Neck Pickups Position 3. Neck Pickup Controls Master Volume (Neck and Bridge Pickup) Strings Fender® Standard Tension™ ST250R, Nickel Plated Steel, Gauges: (.010, .013, .017, .026, .036, .046), (p/n 0730250206) Incl. Accessories Case: Standard Tolex Case Accessories: Strap, Cable, Jazzmaster Strings®, Sonic Youth ‘Zine, Sticker Sheet Unique Features Satin Lacquer Finish, Satin Black Painted Headstock, Single 727 (Saphire Blue Transparent) Master Volume, Mustang® Style Bridge, Re-Voiced Wide Range Humbucking pickups, Black Anodized Aluminum Pickguard, Sticker Sheet. -

Perfect Partner

PERFECT PARTNER A film by Kim Gordon, Tony Oursler and Phil Morrison starring Michael Pitt and Jamie Bochert, with a live soundtrack performed by Kim Gordon, Jim O’Rourke, Ikue Mori, Tim Barnes and DJ Olive As a significant figure of alternative/avant-garde rock and one of the founders of Sonic Youth, Kim Gordon is a truly creative spirit. Enigmatic, iconic, original and multi- faceted, she is increasingly working in the medium of visual arts and diversifying her music projects into more experimental territory. Perfect Partner is a first time collaboration between Kim Gordon, highly renowned artist Tony Oursler and acclaimed filmmaker Phil Morrison. In a response to America’s enchantment with car culture, this surreal psychodrama-cum-road movie starring Michael Pitt (The Dreamers, Hedwig And the Angry Inch, Bully and Gus Van Sant’s upcoming Last Days) and Jamie Bochert unfolds to a thundering free rock live soundtrack. The sound world of Perfect Partner is textural improvised music breaking into occasional songs that interact with the narrative of the film. Kim Gordon is joined on stage by fellow Sonic Youth collaborator, producer extraordinaire, composer and School Of Rock collaborator Jim O’Rourke, percussionist Tim Barnes, laptop virtuoso Ikue Mori and turntablist DJ Olive. Audiences across the UK should fasten their seatbelts for an invigorating trip through live music, video and projection in this one-off cross media adventure. Gordon and Oursler’s shared fascination with the dream lifestyle promised by car manufacturers, and the aspirational language of car advert copy (selling cars as our ‘perfect partner’), provided the inspiration for this hugely inventive project. -

Social Photography VI Prints Available Online from June 28Th At: Socialphotography.Carriagetrade.Org See Details on Purchasing Below*

Joianne Bittle, Empty Met - European paintings gallery, 2018 Social Photography VI Prints available online from June 28th at: socialphotography.carriagetrade.org See details on purchasing below* Online Sales Begin: Thursday, June 28 Gallery Exhibition Opens: Tuesday, July 10, 6-8 PM carriage trade 277 Grand St, 2nd Fl. New York, NY 10002 First presented in 2011, carriage trade’s Social Photography exhibitions have catalogued the rapid transformation of cell phone photography over the last several years. From a novelty medium existing between the voice and text functions of flip phones, to the smart phone as near physical appendage capable of recording and transmitting every waking moment, the cell phone camera now plays a pervasive role in many people’s lives. While Instagram tends to emphasize the medium’s social utility, carriage trade’s Social Photography exhibitions have tracked an alternate course, inviting participants and viewers to encounter these images in a format free of peer-generated tallies, while offering the option of a sustained look afforded by a gallery setting. Social Photography contributors are not limited to visual artists, and include writers, curators, musicians, students, etc., reflecting the accessibly and ubiquity of cell phone camera use. Functioning as a benefit exhibition to help support upcoming programming at carriage trade, there is no particular theme guiding Social Photography VI apart from how the cell phone camera is most often used. Participants email images from their phones to carriage trade, which are then formatted, printed on 7" x 5" paper, and sold online and in the gallery during the exhibition. Less a sanctioning of an evolving medium than a hybrid of a traditional exhibition format and the wider net of social media, Social Photography also functions as a means to sustain and expand carriage trade’s community, which exists in the combined spheres of online experience and the irreplaceable physicality of the exhibition space itself. -

Now Theatre & Dance

apr 20 now Hello! The arts can be a powerful tool for influencing how to understand the world around us, particularly when it comes to experiences we haven’t had personally. While this can be positive, it can also result in reducing communities to cliché. This is particularly true for people with autism, who often are portrayed in cinema in a reductionist manner. Our season Autism and Cinema: An exploration of neurodiversity (see pages 5-6) seeks to change that, and asks us to consider what we might learn about our own worldview by looking at it from an autistic perspective. Pondering on identity is also something that’s occupied photographer Hans Eijkelboom, whose work forms part of our major exhibition Masculinities: Liberation through Photography (page 12); while Virginia Woolf’s ground- breaking novel Orlando also explores what identity means – as Katie Mitchell and Alice Birch’s adaptation (page 13) shows. Also this month we welcome back Shards – the pioneering vocal group (page 2), and conductor Jaap van Zweden for his first concerts in London as the Music Director of the New York Phil (page 4). There’s exciting news about a new fashion range we’re producing (page 18), and if you want to get hands-on, head for one of our workshops (page 17). Contents Now The Barbican Young Visual Arts Group prepare for their showcase Highlights What’s coming up this month 1–4 A spectrum of perspectives 5–6 Cinema 7–8 Next Classical Music 9–10 Art & Design 11 Theatre & Dance 13 Contemporary Music 14 generation art Soon Book now for these Uncover work by promising artists forthcoming events 15–16 at our special showcase. -

His 2008 02 Nd 02.Indd 1 3.3.2008 0:05:32 Deutsch Nepal

editorial obsah Glosář Matěj Kratochvíl 2 Barbez Karel Veselý 4 Volapük / Ovo Petr Ferenc 5 Opening Performance Orchestra Petr Ferenc 6 aktuálně Charalambides Matěj Kratochvíl 7 Vážení a milí čtenáři, Člověk jdoucí za hudebním zážitkem většinou ví, co jej čeká, co má sledovat a očekávat a jak se chovat. Že se bude hrát na harfy či laptopy, že se má tleskat po só- Zvuky v prostoru Jozef Cseres 8 lech či netleskat po větách symfonie, že zvuky se bu- dou linout z pódia a bude víceméně jasné, kdo je vydá- vá. Jsou tu prostě určité jistoty. Zajímá-li nás inspirativní Orbis pictus Petr Ferenc 12 nejistota, je pole zvukových instalací nebo sound artu dobrou volbou. Především můžeme váhat, zda jde vů- bec o hudbu, zvláště když řada tvůrců přichází z výtvar- téma Instalace Alvina Luciera Thomas Bailey 18 ného břehu. Každé jednotlivé dílo pak nabízí svou vlast- ní sadu nejistot a příležitostí k podivu: Jsou tyto zvuky Zvuk – umění – město Karel Veselý 20 elektronické, nebo akustické? Jak souvisí to, co vidím, s tím, co slyším? V takto pomezním oboru je nějaký systematický pře- Steve Roden Pavel Zelinka 22 hled ještě o chlup nemožnější než ve sférách čistě hu- debních, toto číslo tedy nabízí spíše sondy do pestrosti přístupů. Od historických mezníků, jaký představu- je třeba dílo Alvina Luciera Bird And Person Dyning, se dostaneme k autorům výstavy Orbis Pictus, kte- Gordon Monahan Jesse Stewart 25 rá v současnosti s úspěchem koluje po světě, od vy- prázdněných reproduktorů Gordona Monahana přesko- číme k telefonům Dona Rittera, zpívajícím buddhistickou Valentin Silvestrov Vítězslav Mikeš 28 mantru. -

4 Arrests in Meth Bust

Community COMMUNITY sports digest Friday Local happenings .................................Page A-3 ..........Page A-6 July 25, 2008 INSIDE Mendocino County’s World briefly The Ukiah local newspaper .....Page A-10 Saturday: Sunny H 92º L 54º 7 58551 69301 0 Sunday: Mostly sunny H 94º L 53º 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 40 pages, Volume 150 Number 107 email: [email protected] Arson arrest in Covelo fire 4 arrests in meth bust The Daily Journal A Covelo woman has been arrested on charges of arson for allegedly setting fire to an uninhabited building on Lovell Street in Covelo Monday afternoon, according to reports from the Mendocino County Sheriff’s Office. According to sheriff’s reports, Allison Low, 49, of Covelo, went into an uninhabited build- ing at 76201 Lovell Street to scavenge for items the previous tenants may have aban- doned. When she was unable to find what she was looking for, Low allegedly set fire to the build- ing, according to sheriff’s reports. Firefighters from the Covelo Volunteer Fire Department and Cal Fire were summoned to See FIRE, Page A-10 FOLLOW-UP Willits man, 26, killed in collision By BEN BROWN The Daily Journal The Mendocino County Coroners Office has identified the driver of a 1994 Ford pickup who died when the truck collided with a tree off Eastside Road Monday night. Myhrlin Joseph Dionne, 26, of Willits, was driving the truck with an unnamed woman from Scotts Valley when, for unknown reasons, the truck crossed the center divider and left the southern edge of the roadway, where it collided Sarah Baldik/The Daily Journal with a tree, according to reports from the Jonathan Cisneros, 19, is placed under arrest on four outstanding warrants Thursday afternoon, after officers from the California Highway Patrol.