An Interpretation of the Essence of Goal-Setting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 335 443 CE 057 484 AUTHOR Bossort

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 335 443 CE 057 484 AUTHOR Bossort, Patty, Ed.; And Others TITLE Literacy 2000: Make the Next Ten Years Matter. Conference Summary (New Westminster, British Columbia, October 18-21, 1990). INSTITUTION British Columbia Ministry of Advanced Education, Training and Technology, Victoria.; Douglas Coll., New Westminster (British Columbia).; National Literacy Secretariat, Ottawa (Ontario). REPORT NO ISBN-0-7718-8995-X PUB DATE Oct 90 NOTE 184p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; Adult Literacy; *Community Involvement; Community Services; Cultural Awareness; Demonstration Programs; Developed Nations; Foreign Countries; *Illiteracy; Industrial Education; *Literacy Education; Models; Multicultural Education; On the Job Training; *Outreach Programs; Program Effectiveness; Recruitment; Research Utilization; Teacher Certification; Teacher Education IDENTIFIERS Canada; England; Wales; *Workplace Literacy ABSTRACT _. This conference summary contains 36 presentations. Participants' comments, taken from response cards, are quoted . throughout. Presentations from the Opening Plenary include a keynote address--"What Is Literacy?: Critical Issues for the Next Decade" (John Ryan) and four "Panzlist Presentations" (Francis Kazemek, Lorraine Fox, Joyce White, Robin Silverman). Papers in the section, "Evening with Fernando Cardenal," are "Background" (Evelyn Murialdo); "Introduction" (David Cadman); "Special Presentation" (Fernando Cardenal); and "Closing -

M-Phazes | Primary Wave Music

M- PHAZES facebook.com/mphazes instagram.com/mphazes soundcloud.com/mphazes open.spotify.com/playlist/6IKV6azwCL8GfqVZFsdDfn M-Phazes is an Aussie-born producer based in LA. He has produced records for Logic, Demi Lovato, Madonna, Eminem, Kehlani, Zara Larsson, Remi Wolf, Kiiara, Noah Cyrus, and Cautious Clay. He produced and wrote Eminem’s “Bad Guy” off 2015’s Grammy Winner for Best Rap Album of the Year “ The Marshall Mathers LP 2.” He produced and wrote “Sober” by Demi Lovato, “playinwitme” by KYLE ft. Kehlani, “Adore” by Amy Shark, “I Got So High That I Found Jesus” by Noah Cyrus, and “Painkiller” by Ruel ft Denzel Curry. M-Phazes is into developing artists and collaborates heavy with other producers. He developed and produced Kimbra, KYLE, Amy Shark, and Ruel before they broke. He put his energy into Ruel beginning at age 13 and guided him to RCA. M-Phazes produced Amy Shark’s successful songs including “Love Songs Aint for Us” cowritten by Ed Sheeran. He worked extensively with KYLE before he broke and remains one of his main producers. In 2017, Phazes was nominated for Producer of the Year at the APRA Awards alongside Flume. In 2018 he won 5 ARIA awards including Producer of the Year. His recent releases are with Remi Wolf, VanJess, and Kiiara. Cautious Clay, Keith Urban, Travis Barker, Nas, Pusha T, Anne-Marie, Kehlani, Alison Wonderland, Lupe Fiasco, Alessia Cara, Joey Bada$$, Wiz Khalifa, Teyana Taylor, Pink Sweat$, and Wale have all featured on tracks M-Phazes produced. ARTIST: TITLE: ALBUM: LABEL: CREDIT: YEAR: Come Over VanJess Homegrown (Deluxe) Keep Cool/RCA P,W 2021 Remi Wolf Sexy Villain Single Island P,W 2021 Yung Bae ft. -

The Way It Is

The way it is By Ajahn Sumedho 1 Ajahn Sumedho 2 Venerable Ajahn Sumedho is a bhikkhu of the Theravada school of Buddhism, a tradition that prevails in Sri Lanka and S.E. Asia. In this last century, its clear and practical teachings have been well received in the West as a source of understanding and peace that stands up to the rigorous test of our current age. Ajahn Sumedho is himself a Westerner having been born in Seattle, Washington, USA in 1934. He left the States in 1964 and took bhikkhu ordination in Nong Khai, N.E. Thailand in 1967. Soon after this he went to stay with Venerable Ajahn Chah, a Thai meditation master who lived in a forest monastery known as Wat Nong Pah Pong in Ubon Province. Ajahn Chah’s monasteries were renowned for their austerity and emphasis on a simple direct approach to Dhamma practice, and Ajahn Sumedho eventually stayed for ten years in this environment before being invited to take up residence in London by the English Sangha Trust with three other of Ajahn Chah’s Western disciples. The aim of the English Sangha Trust was to establish the proper conditions for the training of bhikkhus in the West. Their London base, the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara, provided a reasonable starting point but the advantages of a more gentle rural environment inclined the Sangha to establishing a forest monastery in Britain. This aim was achieved in 1979, with the acquisition of a ruined house in West Sussex subsequently known as Chithurst Buddhist Monastery or Cittaviveka. -

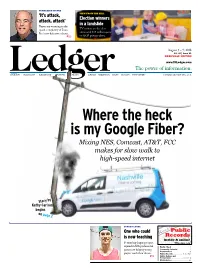

Where the Heck Is My Google Fiber? Mixing NES, Comcast, AT&T, FCC Makes for Slow Walk to High-Speed Internet

TENNESSEE TITANS ‘It’s attack, attack, attack’ Players are warming to the speed, complexity of Dean Pees’ new defensive scheme. VIEW FROM THE HILL Election winners in a landslide TV stations are the clear P23 victor with $45 million spent on GOP primary alone. DAVIDSON • WILLIAMSON • RUTHERFORD • CHEATHAM WILSON SUMNER• ROBERTSON • MAURY • DICKSON • MONTGOMERY LedgerP3 August 3 – 9, 2018 The power of information.NASHVILLE Vol. 44 EDITION | Issue 31 www.TNLedger.com Where the heck FORMERLY WESTVIEW SINCE 1978 is my Google Fiber? Page 13 Mixing NES, Comcast, AT&T, FCC Dec.: Dec.: Keith Turner, Ratliff, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Resp.: Kimberly Dawn Wallace, Atty: Mary C Lagrone, 08/24/2010, 10P1318 makes for slow walk to In re: Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates,Dec.: Resp.: Kim Prince Patrick, Angelo Terry Patrick, Gates, Atty: Monica D Edwards, 08/25/2010, 10P1326 In re: Keith Turner, TN Dept Of Correction, www.westviewonline.com TN Dept Of Correction, Resp.: Johnny Moore,Dec.: Melinda Atty: Bryce L Tomlinson, Coatney, Resp.: Pltf(s): Rodney A Hall, Pltf Atty(s): n/a, 08/27/2010, 10P1336 In re: Kim Patrick, Terry Patrick, Pltf(s): Sandra Heavilon, Resp.: Jewell Tinnon, Atty: Ronald Andre Stewart, 08/24/2010,Dec.: Seton Corp 10P1322 high-speed internet Insurance Company, Dec.: Regions Bank, Resp.: Leigh A Collins, In re: Melinda L Tomlinson, Def(s): Jit Steel Transport Inc, National Fire Insurance Company, Elizabeth D Hale, Atty: William Warner McNeilly, 08/24/2010, Def Atty(s): J Brent Moore, -

Stephen King * the Mist

Stephen King * The Mist I. The Coming of the Storm. This is what happened. On the night that the worst heat wave in northern New England history finally broke-the night of July 19-the entire western Maine region was lashed with the most vicious thunderstorms I have ever seen. We lived on Long Lake, and we saw the first of the storms beating its way across the water toward us just before dark. For an hour before, the air had been utterly still. The American flag that my father put up on our boathouse in 1936 lay limp against its pole. Not even its hem fluttered. The heat was like a solid thing, and it seemed as deep as sullen quarry-water. That afternoon the three of us had gone swimming, but the water was no relief unless you went out deep. Neither Steffy nor I wanted to go deep because Billy couldn't. Billy is five. We ate a cold supper at five-thirty, picking listlessly at ham sandwiches and potato salad out on the deck that faces the lake. Nobody seemed to want anything but Pepsi, which was in a steel bucket of ice cubes. After supper Billy went out back to play on his monkey bars for a while. Steff and I sat without talking much, smoking and looking across the sullen flat mirror of the lake to Harrison on the far side. A few powerboats droned back and forth. The evergreens over there looked dusty and beaten. In the west, great purple thunderheads were slowly building up, massing like an army. -

3HM-15K Honors Project

Three Hard Misses To Fifteen Kisses Melody Johnson “Hearts will never be practical until they can be made unbreakable.” ~The Wizard of Oz One Monday The basement was a dustier version of the wreck I’d ignored nine months ago. I stood rooted at the bottom of our basement stairs, transfixed in horror and clutching the cold, chipped, metal banister as I absorbed the monstrosity of what used to be my father’s bedroom. I couldn’t sort through this crap with a hired search and rescue team, an unlimited supply of Aderoll, and with my sanity intact even if I made a deal with Al Pacino let alone by the end of the summer, I thought miserably. Frank could have labeled each box with his harsh, slashing handwriting, taped their flaps securely with clear packaging tape, and stashed them in his girlfriend’s basement when he moved in with her nine years ago. He could have at least stacked them neatly and covered them with a garbage bag in the corner of Mama Margoe’s basement instead of leaving them scattered randomly over the cement floor to collect dust— a couple on the rug next to the slanted planks he’d used for book shelves, five in a precarious pile near the bed, one on the desk— so when he died last fall, Margoe’s claim that the boxes were, “just fine as they are, for heaven’s sake Patricia,” could have been legitimate. I hadn’t rummaged through them when he left. While he’d been with Susan it had felt like an invasion of privacy, as if he might have returned for them or might have needed them or might have realized that he belonged back here with us. -

Summer/Fall: Volume 7, Issue 2

[Type here] [Type here] [Type here] bioStories sharing the extraordinary in ordinary lives Like the image that graces the cover of the Summer/Fall Issue for 2017, in this volume you will encounter unexpected, sometimes long forgotten gems. You will meet people you won’t soon forget, alongside some that have haunted their authors for a lifetime, while others have proven elusive or were never known by those now narrating a slice of their lives. Many of the eighteen essays you find in this issue are united by telling stories of change and transformation, recognizing that growth that takes place in us as we open ourselves to others’ lives and experiences. Certainly, we have felt changed by the process of reading these diverse stories and are pleased for the chance to share them with you. Cover Art: “Rummage Sale” by John Chavers (photograph). This piece has previously appeared in issues of Gravel and THAT Literary Review. bioStories is edited by Mark Leichliter and is based in Bigfork, MT. We offer new work every week on-line at www.biostories.com. bioStories Magazine 2 Volume 7, Issue 2 Table of Contents Arribadas by M.K. Hall ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Hide and Seek by Steven Wineman ................................................................................................................ 9 Proxy by Paul Juhasz ........................................................................................................................................ -

Skeleton-Crew-Stephen-King-Use

This book is for Arthur and Joyce Greene I’m your boogie man that’s what I am and I’m here to do whatever I can ... —K.C. and the Sunshine Band Contents Title Page Dedication Epigraph Introduction The Mist Here There Be Tygers The Monkey Cain Rose Up Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut The Jaunt The Wedding Gig Paranoid: A Chant The Raft Word Processor of the Gods The Man Who Would Not Shake Hands Beachworld The Reaper’s Image Nona For Owen Survivor Type Uncle Otto’s Truck Morning Deliveries (Milkman #1) Big Wheels: A Tale of The Laundry Game (Milkman #2) Gramma The Ballad of the Flexible Bullet The Reach Notes Copyright Page Do you love? Introduction Wait—just a few minutes. I want to talk to you ... and then I am going to kiss you. Wait ... I Here’s some more short stories, if you want them. They span a long period of my life. The oldest, “The Reaper’s Image,” was written when I was eighteen, in the summer before I started college. I thought of the idea, as a matter of fact, when I was out in the back yard of our house in West Durham, Maine, shooting baskets with my brother, and reading it over again made me feel a little sad for those old times. The most recent, “The Ballad of the Flexible Bullet,” was finished in November of 1983. That is a span of seventeen years, and does not count as much, I suppose, if put in comparison with such long and rich careers as those enjoyed by writers as diverse as Graham Greene, Somerset Maugham, Mark Twain, and Eudora Welty, but it is a longer time than Stephen Crane had, and about the same length as the span of H. -

A SONG of ICE and FIRE Throwing Snow Returns to Houndstooth with His Conceptual ‘Embers’ LP

MUSIC TUNED UP 2017’s first dancefloor weapons p.110 OPUS PRIME January’s top albums p.128 ALL IN THIS TOGETHER Compilations not to miss this month p.132 A SONG OF ICE AND FIRE Throwing Snow returns to Houndstooth with his conceptual ‘Embers’ LP... p.130 djmag.com 109 HOUSE BEN ARNOLD Kian T Room 69 EP Toy Tonics QUICKIES 8.5 Last Waltz If there's a hotter label on the Tunnel Snakes [email protected] house scene at the moment, it Me Me Me would have to cleverly distract 8.0 Toy Tonics from its current Man Power's Me Me Me imprint presents this from proliferation. This latest slab Last Waltz. ‘Y'ave Changed’ is the one, a twinkling is from Kian T (geddit?), a slab of Balearic-tinged delight. There's a remix from 'mysterious Italian producer', the very hot Red Axes too. who constructs bumpy, funk- laden house music from up a hill Simon Garcia somewhere in wine country. These Trimmer EP are indeed drunken grooves, Pets Recordings notably the magnificent 'Good 8.0 Things', a mucky, p-funked romp. Madrid's Simon Garcia drops this for Pets, the 'Room 69' too wobbles in all the highlight being a dancefloor-ready, organ-heavy, right places. Bonus track 'In My laser-noise-blasting remix from Karlovak main man, Eyes' nails down the wayward Mr. Tophat. Hats off. percussion; skippy and brilliant. NVOY Folamour Make You Mine Shakkei Black Butter All-City 7. 5 8.5 Can't argue with this. Fat, brassy stabs, diva vocals, Lovely work from Frenchman, and production so shiny you could eat your dinner Folamour, aka Bruno B, co- off it. -

Clyburn Announces Bid for Majority Whip

Don’t miss out on Parade of Shops on Sunday A2 Clarendon Pilot Club busy baking biscuits for annual bazaar SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894 A7 FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 9, 2018 75 CENTS Archie Parnell, the democratic nominee for the Clyburn announces state’s 5th Congressional District, is seen after voting at Willow Drive bid for majority whip Elementary on Tuesday. FROM STAFF REPORTS urge votes according to offi- He pointed to the diversity MICAH GREEN / Clyburn announces bid for cial party position. Clyburn, of the incoming 116th Con- THE SUMTER ITEM majority whip who has been in Congress gress, "with more women, While the 5th District fea- since 1993 and secured 70.5 people of color and LGBTQ tured two a first full-term percent of Tuesday's votes in colleagues taking the oath of representative and a political the midterm office than every before," say- newcomer, the other congres- elections, ing these new congressmen sional district covering Sum- served as ma- and congresswoman "build a Parnell disappointed, ter has news of a longtime in- jority whip representative government." cumbent trying to make an from 2007-2011. He said in discussions with even further mark on Con- Clyburn said current and freshman legis- proud of race he ran gress. in an open letter lators he has heard the want U.S. House Assistant Dem- CLYBURN to his incoming to end the influence of ocratic Leader James E. Jim Democratic col- money and special interests; BY BRUCE MILLS shortly after arriving back Clyburn, representative for leagues he is make the Rules of the House [email protected] home. -

NA-D Kodulehel.Xlsx

Esitaja Pealkiri Laurent Couson [ SACEM ]Publishers Magical Child "A Wedding March...sort of.... " "A Wedding March...sort of.... " "Boog-it" Jonathan Stout featuring Laura Windley "Cry Me A River Matthew Stone "Lullaby" (Aviva's And Henrietta's Theme Nathan Larson & Nina Persson (Saint Motel) -Sax Cover Daniele Vitale My Type [Ex] da Bass & IAN BREARLEY HOLD ON [EX] DA BASS [+] JANA KASK LIKE A MELODY [Yakut Sakha-Turks] Juliana (Юлияна) Uhuktuu (Уhуктуу) ☓i∪s ¬iИк x VΛVILONΞC Не хочу •You Know You Know Little Willie 1 Awake 1 Dads Return To 115 Hangover 11-59 The Railers 12 EEK Monkey ja Põhja Konn Muusikaline intro KR tunnusmuusika põhjal 148 Debüüt Wash 158 14 Of monster and men Little talks (the knocks remix) 18 Mne Uze Ruki Verh 18 Берез Чиж 1Step4Dub & Awe Las Ma Laulan 1Step4Dub & Awe Sina 1teist €¥¥ 1Teist Feat. Sammalhabe Paduvihm 2 03 Various Artists Javanese Suite 2 Chainz Diamonds Talkin’ Back 2014 Gimn Cosi 25Band Enghad Bekhand 2Kõik Kõik Boyz 2U Sind Vaid Sind 30 Second Timer With Jeopardy Thinking Music 31 Second Timer With Jeopardy Thinking Music 3Pead Armastuse Valgus 3Pead Elame Edasi 3Pead Keelatud Vili 3Pead Paneme Leekima 3Pead Poolel Teel 3Pead Poolel Teel 2013 3Pead Soovide Puu 3Pead Transmitter 3Pead Tuuletõmme 3Pead Uned 3Pead & Bonzo Prostituudi Laul 3Peat Cosmastly 3TM Memory 4 2 Go Bemmi Kummid 4 2 Go Sidur Pidur Gaas Gaas 4 Ever Loetud Päevad 4 Ever Oled Osa Minust 4 Non Blondes l What's Up 42 Go Bemmi Kummid 42 Go Bemmi Kummid (Cheesemaster 5000 Remix) 42Go Feat. More 2 Come Papahh Papahh 4Pead Lillelaps 4Visioon Et Sa Ei Kaoks 4Visioon Feat. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR WILLIAM LUERS Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: May 12th, 2011 Copyright 2018 ADST Q: Today is the 12th of May, 2011 with William, middle initial? LUERS: H. Q: H. Luers, L-U-E-R-S. And this is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, and I’m Charles Stuart Kennedy. And you go by Bill. LUERS: Yes. Q: OK. Let’s start at the beginning. Where and when were you born? LUERS: Born in Springfield, Illinois in 1929 and my father was a banker in Springfield and my mother came from a farming town nearby. Q: OK, let’s talk a little bit about the Luers. Where do they come from? It sounds German. LUERS: They came from Germany, a town just south of Hamburg. My grandfather, Henry Luers, emigrated in the 1880s and married a German lady from the same area. They emigrated to Springfield, Illinois where my grandfather started a shoe store. He had no education, my father had no university education. He had five sons and one daughter who grew up in Springfield. They became prominent citizens of the small town – capital of Illinois. It has a population of about 70,000 which has been rather stable over these many years. Central Illinois had many German speaking citizens before and even after WW1. The Luers Shoe Store was right next door to Lincoln Herndon Law Offices when my grandfather bought it. The Lincoln family had bought shoes from that store.