Paths to Recovery Connecting Habitats to Conserve Wildlife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cloverdale Farm County Park

Ocean County CLOVERDALE Board of Chosen Freeholders John C. Bartlett, Jr. Cloverdale FARM COUNTY Chairman of Parks and Recreation PARK John P. Kelly Within the boundaries of this 90-acre park, James F. Lacey Farm you will find the diversity of the Pine Bar- Gerry P. Little rens wetlands, uplands, and the beauty of 20 Joseph H. Vicari acres of cranberry bogs all year long. County The early settlers of New Jersey referred to the Pine Barrens as “barren” because Park traditional crops grew poorly here. Other types of agriculture were later established in the region. This trail will allow you to experience the natural beauty of the Pine Barrens and delve into its rich historical and agricultural past. Ocean County Department of Parks and Recreation The Ocean County Natural Lands Trust Administrative Offices Fund Program acquired Cloverdale Farm in 1-877-OC-PARKS 2004. The park was the site of the Collins’ family farm, which several generations of Fax: 1-732-270-9464 the family operated, going back to the early www.oceancountyparks.org 1900s. http://www.facebook.com/OceanCountyParks As you meander along the bog edges be sure to keep your eye out for different species of flora and fauna. You might just find one of Michael T. Mangum, our native carnivorous plants luring in ants Director with its false nectar bribes or be amazed by Kenneth F. Pullen, the sheer beauty of mountain laurel in General Supervisor bloom. As you wander, keep your eyes and 34 Cloverdale Road ears open or you might miss a red-tailed Mary Bavais, hawk as it cries soaring overhead or a Superintendent of Recreation Barnegat, NJ bluebird on its morning forage for insects. -

The Natural Communities of South Carolina

THE NATURAL COMMUNITIES OF SOUTH CAROLINA BY JOHN B. NELSON SOUTH CAROLINA WILDLIFE & MARINE RESOURCES DEPARTMENT FEBRUARY 1986 INTRODUCTION The maintenance of an accurate inventory of a region's natural resources must involve a system for classifying its natural communities. These communities themselves represent identifiable units which, like individual plant and animal species of concern, contribute to the overall natural diversity characterizing a given region. This classification has developed from a need to define more accurately the range of natural habitats within South Carolina. From the standpoint of the South Carolina Nongame and Heritage Trust Program, the conceptual range of natural diversity in the state does indeed depend on knowledge of individual community types. Additionally, it is recognized that the various plant and animal species of concern (which make up a significant remainder of our state's natural diversity) are often restricted to single natural communities or to a number of separate, related ones. In some cases, the occurrence of a given natural community allows us to predict, with some confidence, the presence of specialized or endemic resident species. It follows that a reasonable and convenient method of handling the diversity of species within South Carolina is through the concept of these species as residents of a range of natural communities. Ideally, a nationwide classification system could be developed and then used by all the states. Since adjacent states usually share a number of community types, and yet may each harbor some that are unique, any classification scheme on a national scale would be forced to recognize the variation in a given community from state to state (or region to region) and at the same time to maintain unique communities as distinctive. -

Carolina Sandhills General Brochure

Carolina Sandhills National Wildlife Refuge Numerous small creeks and tributaries flow through the Carolina Sandhills U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (NWR) encompasses approximately 45,000 refuge and drain into either Black Creek on the east side National Wildlife Refuge and Lynches River on the west side. Atlantic white cedar, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service acres in northeastern South Carolina. The pond pine, and dense stands of evergreen shrubs occur 23734 U.S. Highway 1 refuge is one of more than 560 refuges in along these streams forming pocosin (swamp on a hill) McBee, SC 29101 Carolina Sandhills areas throughout the refuge. Thirty man-made lakes and 843 335 8401 office the National Wildlife Refuge System, the ponds and 1,200 acres of old fields, forest openings, and world’s most outstanding network of lands and cultivated fields contribute to the diverse habitats found on http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Carolina_Sandhills National Wildlife the refuge. waters dedicated to wildlife the conservation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Refuge management, and where appropriate, restoration Refuge Wildlife 1 800/344 WILD of the fish, wildlife, and plant resources The refuge supports a diverse assemblage of plants and http://www.fws.gov animals including more than 190 species of birds, 42 and their habitats for the benefit of present and species of mammals, 41 species of reptiles, 25 species of August 2019 future generations of Americans. amphibians, 62 species of butterflies and moths, 56 species of native bees, and more than 800 species of plants! Refuge History In 1939 the federal government purchased land under Threatened and Endangered Species the provisions of the Resettlement Act. -

Imperiled Treasures: Wetlands at Risk

Table of Contents Green-backed herons live near fresh and salt water lakes, streams, shores, swamps, marshes, rivers and ponds. Curiously, they are known to use bait (feathers, insects, twigs, moss, etc.) to lure fish. Introduction .............................................. 2 Southeast.................................................. 4 Northeast/Mid-Atlantic .............................. 6 Great Lakes/Upper Mississippi........................ 8 The Great Plains ........................................ 10 Southwest ................................................ 12 West/Great Basin........................................ 14 Alaska .................................................... 16 Hawaii .................................................... 18 Conclusion................................................ 19 Endnotes .................................................. 20 Other Sources ............................................ 20 Photo Credits ............................................ 20 A report by the National Wildlife Federation and Natural Resources Defense Council 1 Introduction America’s wetlands are in danger. Thirty years after passage of the Clean Water Act, wetlands continue to be drained, filled and polluted at an alarming rate. So-called “isolated wetlands” are in particular peril, due in great measure to a recent Supreme Court decision potentially jeopardizing federal Clean Water Act protections for millions of acres of waters and wetlands. exclude waters determined to be “isolated” from pro- tection under the Clean -

Wetlands.Pdf

Table of Contents Green-backed herons live near fresh and salt water lakes, streams, shores, swamps, marshes, rivers and ponds. Curiously, they are known to use bait (feathers, insects, twigs, moss, etc.) to lure fish. Introduction .............................................. 2 Southeast.................................................. 4 Northeast/Mid-Atlantic .............................. 6 Great Lakes/Upper Mississippi........................ 8 The Great Plains ........................................ 10 Southwest ................................................ 12 West/Great Basin........................................ 14 Alaska .................................................... 16 Hawaii .................................................... 18 Conclusion................................................ 19 Endnotes .................................................. 20 Other Sources ............................................ 20 Photo Credits ............................................ 20 A report by the National Wildlife Federation and Natural Resources Defense Council 1 Introduction America’s wetlands are in danger. Thirty years after passage of the Clean Water Act, wetlands continue to be drained, filled and polluted at an alarming rate. So-called “isolated wetlands” are in particular peril, due in great measure to a recent Supreme Court decision potentially jeopardizing federal Clean Water Act protections for millions of acres of waters and wetlands. exclude waters determined to be “isolated” from pro- tection under the Clean -

Final Environmental Statement Related to the Forked River Nuclear

~,~~afjF~M flV~~3 ~ '*-'a- qi'4a' 0.nv,.-.tn, WSie related to the FORKED RIVER NUCLEAR STATION UNIT I JERSEY CENTRAL POWER AND LIGHT COMPANY DOCKET No. 50-363 February 1973 UNITED STATES ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION DIRECTORATE OF LICENSING i SUM~MARY AND CONCLUSIONS This Final Environmental Statement was prepared by the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission, Directorate of Licensing. 1. This action is administrative. 2. The proposed action is the issuance of a construction permit to the Jersey Central Power and Light Company (hereafter the Applicant) for the construction of the Forked River Nuclear Station Unit 1 (hereafter the Station), a nuclear power reactor to be located a few miles inland from Barnegat Bay near the community of Forked River, Ocean County, New Jersey (Docket No. 50-363). Unit 1 will employ a pressurized water reactor' to produce up to 3390 megawatts thermal (MWt)'. A steam turbine-generator will use this heat to provide 1093 megawatts of electrical power capacity (MWe). A "stretch power level" of 1143 MWe is anticipated at-a future date and is considered in the assessments contained in this statement. The turbine-exhaust steam will be cooled with seawater obtained from a canal connected to Barnegat Bay and circulated through either a counter-flow or cross-flow, natural-draft cooling tower. The interaction of the Forked River Station with the nearby operating Oyster Creek Nuclear Station was considered in this statement in evaluating environmental impacts. The existing environmental conditions with the Oyster Creek Station operating were used as an evaluation baseline. The Staff analysis showed no significant compounding of potential adverse effects attributable to th e addition of the Forked River Station. -

PINELANDS New Jersey’S PINELANDS Wildlife Action Plan

PINELANDS New Jersey’s PINELANDS Wildlife Action Plan Stronghold for Globally Rare Wildlife Enter a region of vast pitch pine forests and Atlantic white cedar swamps that shelter globally rare plants and animals such as the Pine Barrens tree frog. The New Jersey’s reliance of rare wildlife on specialized habitats means Frosted elfin they live close to a tipping point; every animal in the Four-toed salamander Wildlife Action Plan State threatened Conservation concern The southern part of the population matters. Their survival depends on the The smallest of New Jersey’s 16 Creating a Network Pinelands shelters one of the connected forests of the Pinelands that are important salamander species, the four- world’s largest colonies of toed salamander inhabits wooded for Conservation frosted elfin butterflies. Look for for nesting songbirds and serve as migratory bird swamps and bogs throughout the this small butterfly on utility line stopovers. Today’s top challenges are to mimic the Pinelands. Females usually lay rights-of-way and at airports their eggs in nests of sphagnum To protect our wildlife of greatest conservation where the caterpillars depend historic role of fire in shaping this ecosystem, to moss that are overhanging need, the New Jersey Department of on wild indigo host plants for maintain intact forests and unique habitat types, and streams. The adults are just Environmental Protection’s Division of Fish their survival. 2 inches to 3 ½ inches long. to protect wildlife from the hazards of roads. and Wildlife led many partners to develop and Conserving implement the state’s Wildlife Action Plan. -

Wildlife Disease and Habitat Modification Paola Dolcemascolo Montclair State University

Montclair State University Montclair State University Digital Commons Theses, Dissertations and Culminating Projects 5-2014 Anthropogenic Disturbance of the Herpetofauna in the Northeast US : Wildlife Disease and Habitat Modification Paola Dolcemascolo Montclair State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Dolcemascolo, Paola, "Anthropogenic Disturbance of the Herpetofauna in the Northeast US : Wildlife Disease and Habitat Modification" (2014). Theses, Dissertations and Culminating Projects. 60. https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/etd/60 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Montclair State University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Culminating Projects by an authorized administrator of Montclair State University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANTHROPOGENIC DISTURBANCE OF THE HERPETOFAUNA IN THE NORTHEAST US: WILDLIFE DISEASE AND HABITAT MODIFICATION A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of Montclair State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by PAOLA DOLCEMASCOLO Montclair State University Upper Montclair, NJ 2014 Dissertation Chair: Kirsten Monsen-Collar, PhD Copyright © 2014 by Paola Dolcemascolo. All rights reserved. ABSTRACT ANTHROPOGENIC DISTURBANCE OF THE HERPETOFAUNA IN THE NORTHEAST US: WILDLIFE DISEASE AND HABITAT MODIFICATION by -

Kirkwood-Cohansey Project

KirKwood-Cohansey ProjeCt the Potential imPaCt of simulated Groundwater withdrawals on the oviPosition, larval develoPment, and metamorPhosis of Pond-breedinG froGs Cover: A calling male Pine Barrens tree frog (Hyla andersonii). Photograph taken by John F. Bunnell. KirKwood-Cohansey ProjeCt the Potential imPaCt of simulated Groundwater withdrawals on the oviPosition, larval develoPment, and metamorPhosis of Pond-breedinG froGs John F. Bunnell and JenniFer l. Ciraolo 2010 Pinelands Commission P.o. Box 359 new lisBon, new Jersey The Pinelands Commission Candace McKee Ashmun, Acting Chair John A. Haas, Acting Vice Chair William J. Brown Daniel M. Kennedy Dr. Guy Campbell, Jr. Judith Y. Link Leslie M. Ficcaglia Edward Lloyd Paul E. Galletta Ed McGlinchey Lloyd Henderson, Jr. Robert W. McIntosh, Jr. Robert Jackson Francis A. Witt John C. Stokes, Executive Director For more information on the Pinelands Commission, the Kirkwood-Cohansey Project, and other Science Office publications visit: http://www.state.nj.us/pinelands http://www.state.nj.us/pinelands/science/current/kc http://www.state.nj.us/pinelands/science/pub Suggested citation: Bunnell, J. F. and J. L. Ciraolo. 2010. The potential impact of simulated groundwater withdrawals on the oviposition, larval development, and metamorphosis of pond-breeding frogs. Pinelands Commission, New Lisbon, New Jersey, USA. Abstract Wetland hydroperiod is a key factor for the reproductive success of pond-breeding amphibians. Groundwater withdrawals may cause intermittent ponds to dry prematurely, potentially affecting amphibian development. In three intermittent ponds, we monitored hydrology and tracked oviposition, larval development, and metamorphosis for three frog species that represented a range of breeding phenologies. The three species were the southern leopard frog (Lithobates sphenocephalus), spring peeper (Pseudacris crucifer), and Pine Barrens treefrog (Hyla andersonii). -

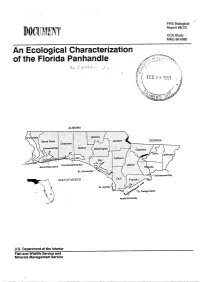

An Ecological Characterization of the Florida Panhandle ,- P,, P,, C Ct\$-.%1 *- J

/ FWS Biological Report 88(12) OCS Study MMS 88-0063 An Ecological Characterization of the Florida Panhandle ,- p,, p,, c ct\$-.%1 *- J ". ALABAMA U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service and Minerals Management Service FWS Biological Report 88(12) OCS Study MMS 88-0063 An Ecological Characterization of the Florida Panhandle Authors Steven H. Wolfe Jeffrey A. Reidenauer State of Florida Department of Environmental Regulations Tallahassee, Florida and D. Bruce Means The Coastal Plains Institute Tallahassee, Florida Prepared under Interagency Agreement 14-1 2-0001-30037 Published by U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington Minerals Management Service, New Orleans October 1988 DISCLAIMER The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or the Minerals Management Service, nor does the mention of trade names constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal Government. Library of Congress Cataloging-In-Publication Data Wolfe, Steven H. An Ecological characterization of the Florida panhandle. Biological report ; 88 (12)) 6 upt. of DOCS.no. : 149. 89/:88(12) "Performed for U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wild- life Service, Research and Development, National Wetlands Research Center, Washington, D.C. and Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf Office, Minerals Management Service, New Orleans, LA." "October 1988." Bibliography: p. 1. Ecology--Florida. 2. Natural history--Florida. I. Reidenauer, Jeffrey A. II. Means, D. Bruce. Ill. National Wetlands Research CenterJU.S.) IV. Unitec! States. Minerals Management Service. Gulf of exlco OCS Reg~on.V. -

Herpetofauna of the New Jersey Pine Barrens

Herpetofauna of the New Jersey Pine Barrens Herpetofauna of the New Jersey Pine Barrens By Robert T. Zappalorti Introduction I recall with fondness my first trip to the New Jersey Pine Barrens, back in June of 1961. I was with my childhood friend and buddy, Jim Bockowski. We were looking for an old clay mining town called Crossley, in Ocean County, but could not find it. Out of desperation we stopped at a gas station in Whiting to ask for directions. We spoke with an elderly man dressed in overalls and a straw hat, and asked if he knew where Crossley was? The local man (known as a “Piney,” a person who lives in the Pine Barrens), was kind enough to say, “follow me, I’m going that way. I’ll show you Crossley Road.” So, Jim and I followed the man in his pickup truck Eastward from Whiting. After about 1.4 miles he slowed down and pointed North towards a non-decrypt sand road, then waived good bye as he continued on his way. We turned left and followed the winding sand road through an extensive pine-oak forest. The over-story trees consisted of pitch pine, short-leaf pine, scrub oak, black-jack oak and sassafras, while the under-story was mostly huckleberry, lowbush blueberry, inkberry and bracken fern. We came to a sandy flat section of the road and had trouble driving in soft white sand, but managed to keep going with some extra speed. After traveling about 0.75 of a mile, we came upon an opening in the forest and an abandoned railroad track that ran from East to West through the pine forest. -

Biological Status Report

Pine Barrens Treefrog Biological Status Review Report March 31, 2011 FLORIDA FISH AND WILDLIFE CONSERVATION COMMISSION 620 South Meridian Street Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1600 Biological Status Review of the Pine Barrens Treefrog (Hyla andersonii) March 31, 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) directed staff to evaluate all species listed as Endangered, Threatened, or Species of Special Concern as of November 8, 2010 that had not undergone a status review in the past decade. Public information on the status of the Florida population of the Pine Barrens treefrog was sought from September 17 through November 1, 2010. A five-member Biological Review Group (BRG) met on November 9-10, 2010. Group members were Bill Turner (FWC lead), Ryan Means (Coastal Plains Institute), Kelly Jones (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University), Paul Moler (independent consultant), and John Himes (FWC) (Appendix 1). In accordance with rule 68A-27.0012, Florida Administrative Code (F.A.C.), the BRG was charged with evaluating the biological status of the Pine Barrens treefrog using criteria included in definitions in 68A-27.001, F.A.C., and following protocols in the Guidelines for Application of the IUCN Red List Criteria at Regional Levels (Version 3.0) and Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria (Version 8.1). Please visit http://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/imperiled/listing-action- petitions/ to view the listing process rule and the criteria found in the definitions. In late 2010, staff developed the initial draft of this report which included BRG findings and a preliminary listing recommendation from staff.