Coal Miner's Daughter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legends in Concert

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 31, 2020 CONTACT: DeAnn Lubell-Ames – (760) 831-3090 Note: Photos available at http://mccallumtheatre.com/index.php/media Legends In Concert: The Divas Tributes To Barbra Streisand, Celine Dion, Whitney Houston And Aretha Franklin McCallum Theatre Thursday – February 27 – 3:00 Pm And 8:00pm Palm Desert, CA – Through the generosity of Harold Matzner, the McCallum Theatre presents Legends in Concert—The Divas, featuring tributes to Barbra Streisand, Celine Dion, Whitney Houston and Aretha Franklin, for two shows: at 3:00pm and 8:00pm, Thursday, Feb. 27. Legends in Concert is the longest-running show in Las Vegas history, and after 35 years is still voted the No. 1 tribute show in the city. The internationally acclaimed and award-winning production is known as the pioneer of live tribute shows, and possesses the greatest collection of live tribute artists in the world. These incredible artists have pitch-perfect live vocals, signature choreography, and stunningly similar appearances to the legends they portray. Jazmine (Whitney Houston) draws her musical inspiration from her Cuban heritage while speaking and singing in both English and Spanish. After deciding to pursue her music career on the European music scene, she earned immediate success. After signing a one-album deal with Finland's K-TEL Records, Jazmine's first single achieved international success: In January 1996, "Love Like Never Before" rose to No. 1 on the French dance chart, dropping Madonna to No. 2 and passing same-week entries from Michael Jackson, Bon Jovi and Whitney Houston. She has appeared on the WB television show Pop Stars and on several episodes of the Dick Clark Productions show Your Big Break. -

Cultural Anthropology Through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-Based Sentiment

Cultural Anthropology through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-based Sentiment Peter A. Gloor, Joao Marcos, Patrick M. de Boer, Hauke Fuehres, Wei Lo, Keiichi Nemoto [email protected] MIT Center for Collective Intelligence Abstract In this paper we study the differences in historical World View between Western and Eastern cultures, represented through the English, the Chinese, Japanese, and German Wikipedia. In particular, we analyze the historical networks of the World’s leaders since the beginning of written history, comparing them in the different Wikipedias and assessing cultural chauvinism. We also identify the most influential female leaders of all times in the English, German, Spanish, and Portuguese Wikipedia. As an additional lens into the soul of a culture we compare top terms, sentiment, emotionality, and complexity of the English, Portuguese, Spanish, and German Wikinews. 1 Introduction Over the last ten years the Web has become a mirror of the real world (Gloor et al. 2009). More recently, the Web has also begun to influence the real world: Societal events such as the Arab spring and the Chilean student unrest have drawn a large part of their impetus from the Internet and online social networks. In the meantime, Wikipedia has become one of the top ten Web sites1, occasionally beating daily newspapers in the actuality of most recent news. Be it the resignation of German national soccer team captain Philipp Lahm, or the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight 17 in the Ukraine by a guided missile, the corresponding Wikipedia page is updated as soon as the actual event happened (Becker 2012. -

MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series

MCA 700 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series: By the time the reissue series reached MCA-700, most of the ABC reissues had been accomplished in the MCA 500-600s. MCA decided that when full price albums were converted to midline prices, the albums needed a new number altogether rather than just making the administrative change. In this series, we get reissues of many MCA albums that were only one to three years old, as well as a lot of Decca reissues. Rather than pay the price for new covers and labels, most of these were just stamped with the new numbers in gold ink on the front covers, with the same jackets and labels with the old catalog numbers. MCA 700 - We All Have a Star - Wilton Felder [1981] Reissue of ABC AA 1009. We All Have A Star/I Know Who I Am/Why Believe/The Cycles Of Time//Let's Dance Together/My Name Is Love/You And Me And Ecstasy/Ride On MCA 701 - Original Voice Tracks from His Greatest Movies - W.C. Fields [1981] Reissue of MCA 2073. The Philosophy Of W.C. Fields/The "Sound" Of W.C. Fields/The Rascality Of W.C. Fields/The Chicanery Of W.C. Fields//W.C. Fields - The Braggart And Teller Of Tall Tales/The Spirit Of W.C. Fields/W.C. Fields - A Man Against Children, Motherhood, Fatherhood And Brotherhood/W.C. Fields - Creator Of Weird Names MCA 702 - Conway - Conway Twitty [1981] Reissue of MCA 3063. -

Morgan Unt:Il Furt:Her St:Udy

.. ' :n··' ~' .. ar . Volume XXVI. Number 25 Law S.tudent-s Board ·Votes N;ot to Elect . ' -- ·Proffer Blood Morgan To Ill Teaeher Unt:il Furt:her St:udy . In the. only contested publication position, Robert S. Gallimore last night Forty Men . From was voted by the Publications Board editor of OLD GOLD AND BLACK for Law School and the year of 194~:43. He defeated Herbert Thompson, the only other candidate Sports V ohmteer to take the positiOn. ' Forty law students and three j · For T~e Student, co1le~e magazine, no ~~itor was elected. Neil Morgan, football players vol'!lllteered ·to present editor, was~a candidate for the positiOn, but the election was postponed •. - have their blood tested for trans-. indefinitely- until it can be establishe~ constitutionally whether or not an editor ,fusion this week when it was - can succeed himself. The present~------------=-=- 'learned t~at P11ofess()r I. B.. Lake . 1constitution of the Publications -uf the law school faculty, now on I ~card ~as be~n lost, and the elec- leave of absence for national de- · 1t10n will await the drafting of a Debaters Take ..-f:ense work in connection with the 'new document. Office of Production Management For all other student publication First Places in Washington, is seriously ill, in , Ipositions only one candidate for Durham's Duke, Hospital with an each had filed application, and infection of the blood stream · In Tournament ,, each was elected with no dissen- ,• which as yet remains a mystery to sion by the Publications Board. Hope, Bell and attending physicians. ' , . New editor of the Howler is Ed- Davi's w· Of the 43 men volunteering, 16 I Yiin Wilson. -

Deana Carter Danny Myrick

Deana Carter DEANA CARTER, the daughter of famed studio guitarist and producer Fred Carter, Jr., grew up surrounded by musical greats, including Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan, Waylon Jennings, and Simon & Garfunkel. She developed her songwriting skills at writer’s nights throughout Nashville, but her real break came when one of her demo tapes fell into the hands of Willie Nelson, who remembered Deana as a child. Impressed with how she’d grown as a songwriter, Nelson asked Deana to perform along with John Mellencamp, Kris Kristofferson, and Neil Young, as the only female solo artist to appear at Farm Aid VII in 1994. Her 1996 debut album Did I Shave My Legs for This? quickly climbed to the top of both the country and pop charts, quickly achieving multi-platinum status. "Strawberry Wine,” the first single from the album, was awarded CMA's 1997 Single of the Year. Seven albums and a decade later, Deana is still writing and producing for both the pop/rock and country markets when not on the road touring. Her superstar success continues to be evident. Her chart topper “You & Tequila,” co-written with Matraca Berg and recorded by Kenny Chesney, was nominated in 2011 as CMA’s “Song of the Year” and received two Grammy nods. Carter also recently co-wrote and produced a new album for recording artist Audra Mae while putting the finishing touches on her own Southern Way of Life that hit the shelves last December. Danny Myrick DANNY MYRICK is an award winning songwriter and musician based here in Nashville. -

Traditional Song

3 TraditionalSong l3-9 Traditional Song Week realizes a dream of a comprehensive program completely devoted to traditional styles of singing. Unlike programs where singing takes a back seat to the instrumentalists, it is the entire focus of this week, which aims to help restore the power of songs within the larger traditional music scene. Here, finally, is a place where you can develop and grow in confidence about your singing, and have lots of fun with other folks devoted to their own song journeys. Come gather with us to explore various traditional song genres under the guidance of experienced, top-notch instructors. When singers gather together, magical moments are bound to happen! For Traditional Song Week’s ninth year and our celebration of The Swannanoa Gathering’s 25th Anniversary, we are proud to present a gathering of highly influential singers and musicians who have remained devoted over the years to preserving and promoting traditional song. Tuesday evening will be our big Hoedown for a Traditional Country, Honk-Tonk, Western Swing Song and Dance Night. Imagine singing to a house band of Josh Goforth, Robin and Linda Williams and Ranger Doug or Tim May, Tim O’Brien, and Mark Weems! So, bring your boots and hats, your voices and instruments, and get ready to bring on the fun! Our Community Gathering Time each day just after lunch affords us the opportunity to experience together, as one group, diverse topics concerning our shared love of traditional song. This year’s spotlight will feature folks who have been “on the road” and singing for quite a while. -

Contemporary Films Related to Content in a Course on Death And

Contemporary Films Related to Content in a Course on Death and Grief Barbara Head, PhD, CHPN, ACSW, FPCN University of Louisville, Kent School of Social Work [email protected] Title Year Leading Actor(s) Brief Synopsis Related Course Content Amour 2012 Jean-Louis Trintignant An elderly, loving couPle struggles to Grief and loss in later life (French) Emmanuelle Riva maintain their indePendence after the Euthanasia wife suffers a Paralyzing stroke. Caregiver stress Anticipatory grief A Single Man 2009 Colin Firth A gay university Professor struggles Disenfranchised grief Julianne Moore with his grief after the sudden death of Suicide risk in bereavement his partner. Story is set in the early Historical/cultural imPacts on grief and 1960’s. loss Beyond Belief 2007 Susan Retik Two women (both Pregnant at the time) Meaning reconstruction (Documentary) Patti Quigley who lost their husbands on 911 find Resiliency meaning in their loss. Sudden, traumatic loss The Descendants 2011 George Clooney A family struggles with the imPending Children and grief Beau Bridges death and infidelity of the mother/wife Disenfranchised grief who is rendered brain dead after a Families and grief boating accident. Discontinuation of life suPPort 50/50 2011 JosePh Gordon-Levitt A young radio journalist faces treatment Counseling the seriously ill Patient Seth Rogan for a serious malignancy with a 50/50 Professional boundaries chance of survival. Grief and loss related to serious illness in a young person Social suPPort during illness Grace is Gone 2007 John Cusack The father of two young daughters Families and grief reacts to the news of the death of his Sudden, traumatic loss wife who was killed during a tour of duty Stages and tasks of grieving in Iraq. -

TEXAS MUSIC SUPERSTORE Buy 5 Cds for $10 Each!

THOMAS FRASER I #79/168 AUGUST 2003 REVIEWS rQr> rÿ p rQ n œ œ œ œ (or not) Nancy Apple Big AI Downing Wayne Hancock Howard Kalish The 100 Greatest Songs Of REAL Country Music JOHN THE REVEALATOR FREEFORM AMERICAN ROOTS #48 ROOTS BIRTHS & DEATHS s_________________________________________________________ / TMRU BESTSELLER!!! SCRAPPY JUD NEWCOMB'S "TURBINADO ri TEXAS ROUND-UP YOUR INDEPENDENT TEXAS MUSIC SUPERSTORE Buy 5 CDs for $10 each! #1 TMRU BESTSELLERS!!! ■ 1 hr F .ilia C s TUP81NA0Q First solo release by the acclaimed Austin guitarist and member of ’90s. roots favorites Loose Diamonds. Scrappy Jud has performed and/or recorded with artists like the ' Resentments [w/Stephen Bruton and Jon Dee Graham), Ian McLagah, Dan Stuart, Toni Price, Bob • Schneider and Beaver Nelson. • "Wall delivers one of the best start-to-finish collections of outlaw country since Wayton Jennings' H o n k y T o n k H e r o e s " -Texas Music Magazine ■‘Super Heroes m akes Nelson's" d e b u t, T h e Last Hurrah’àhd .foltowr-up, üflfe'8ra!ftèr>'critieat "Chris Wall is Dyian in a cowboy hat and muddy successes both - tookjike.^ O boots, except that he sings better." -Twangzirtc ;w o tk s o f a m e re m o rta l.’ ^ - -Austin Chronlch : LEGENDS o»tw SUPER HEROES wvyw.chriswatlmusic.com THE NEW ALBUM FROM AUSTIN'S PREMIER COUNTRY BAND an neu mu - w™.mm GARY CLAXTON • acoustic fhytftm , »orals KEVIN SMITH - acoustic bass, vocals TON LEWIS - drums and cymbals sud Spedai td truth of Oerrifi Stout s debut CD is ContinentaUVE i! so much. -

Jessica Lange Regis Dialogue Formatted

Jessica Lange Regis Dialogue with Molly Haskell, 1997 Bruce Jenkins: Let me say that these dialogues have for the better part of this decade focused on that part of cinema devoted to narrative or dramatic filmmaking, and we've had evenings with actors, directors, cinematographers, and I would say really especially with those performers that we identify with the cutting edge of narrative filmmaking. In describing tonight's guest, Molly Haskell spoke of a creative artist who not only did a sizeable number of important projects but more importantly, did the projects that she herself wanted to see made. The same I think can be said about Molly Haskell. She began in the 1960s working in New York for the French Film Office at that point where the French New Wave needed a promoter and a writer and a translator. She eventually wrote the landmark book From Reverence to Rape on women in cinema from 1973 and republished in 1987, and did sizable stints as the film reviewer for Vogue magazine, The Village Voice, New York magazine, New York Observer, and more recently, for On the Issues. Her most recent book, Holding My Own in No Man's Land, contains her last two decades' worth of writing. I'm please to say it's in the Walker bookstore, as well. Our other guest tonight needs no introduction here in the Twin Cities nor in Cloquet, Minnesota, nor would I say anyplace in the world that motion pictures are watched and cherished. She's an internationally recognized star, but she's really a unique star. -

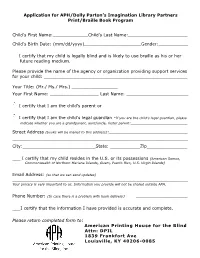

Application for APH/Dolly Parton's Imagination Library Partners

Application for APH/Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library Partners Print/Braille Book Program Child’s First Name:_____________Child’s Last Name:______________________ Child’s Birth Date: (mm/dd/yyyy)_____________________Gender:___________ I certify that my child is legally blind and is likely to use braille as his or her future reading medium. Please provide the name of the agency or organization providing support services for your child: _____________________________________________________ Your Title: (Mr./ Ms./ Mrs.) _________________ Your First Name: __________________ Last Name: _______________________ I certify that I am the child’s parent or I certify that I am the child's legal guardian *If you are the child’s legal guardian, please indicate whether you are a grandparent, aunt/uncle, foster parent:_____________________ Street Address (books will be mailed to this address):_____________________________ _________________________________________________________________ City:___________________________State: ___________Zip_______________ ___ I certify that my child resides in the U.S. or its possessions (American Samoa, Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands) Email Address: (so that we can send updates) _________________________________________________________________ Your privacy is very important to us. Information you provide will not be shared outside APH. Phone Number: (In case there is a problem with book delivery) ________________________ ___I certify that the information I have provided is accurate and complete. Please return completed form to: American Printing House for the Blind Attn: DPIL 1839 Frankfort Ave Louisville, KY 40206-0085 Thank you for your application! If your child is eligible and we enroll him or her in the APH/DPIL Partners Print/Braille Book Program, you will be emailed a welcome letter from Dolly Parton and APH within 10 business days. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Narrative Representations of Gender and Genre Through Lyric, Music, Image, and Staging in Carrie Underwood’S Blown Away Tour

COUNTRY CULTURE AND CROSSOVER: Narrative Representations of Gender and Genre Through Lyric, Music, Image, and Staging in Carrie Underwood’s Blown Away Tour Krisandra Ivings A Thesis Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts in Music with Specialization in Women’s Studies University of Ottawa © Krisandra Ivings, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 Abstract This thesis examines the complex and multi-dimensional narratives presented in the work of mainstream female country artist Carrie Underwood, and how her blending of musical genres (pop, rock, and country) affects the narratives pertaining to gender and sexuality that are told through her musical texts. I interrogate the relationships between and among the domains of music, lyrics, images, and staging in Underwood’s live performances (Blown Away Tour: Live DVD) and related music videos in order to identify how these gendered narratives relate to genre, and more specifically, where these performances and videos adhere to, expand on, or break from country music tropes and traditions. Adopting an interlocking theoretical approach grounded in genre theory, gender theory, narrative theory in the context of popular music, and happiness theory, I examine how, as a female artist in the country music industry, Underwood uses genre-blending to construct complex gendered narratives in her musical texts. Ultimately, I find that in her Blown Away Tour: Live DVD, Underwood uses diverse narrative strategies, sometimes drawing on country tropes, to engage techniques and stylistic influences of several pop and rock styles, and in doing so explores the gender norms of those genres. ii Acknowledgements A great number of people have supported this thesis behind the scenes, whether financially, academically, or emotionally.