Assessing Public Expenditure Governance in Uganda's Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Call to Action to Enhance Filovirus Disease Outbreak Preparedness and Response

Viruses 2014, 6, 3699-3718; doi:10.3390/v6103699 OPEN ACCESS viruses ISSN 1999-4915 www.mdpi.com/journal/viruses Letter A Call to Action to Enhance Filovirus Disease Outbreak Preparedness and Response Paul Roddy Independent Epidemiology Consultant, Barcelona, 08010, Spain; E-Mail: [email protected] External Editor: Jens H. Kuhn Received: 8 September 2014; in revised form: 23 September 2014 / Accepted: 23 September 2014 / Published: 30 September 2014 Abstract: The frequency and magnitude of recognized and declared filovirus-disease outbreaks have increased in recent years, while pathogenic filoviruses are potentially ubiquitous throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Meanwhile, the efficiency and effectiveness of filovirus-disease outbreak preparedness and response efforts are currently limited by inherent challenges and persistent shortcomings. This paper delineates some of these challenges and shortcomings and provides a proposal for enhancing future filovirus-disease outbreak preparedness and response. The proposal serves as a call for prompt action by the organizations that comprise filovirus-disease outbreak response teams, namely, Ministries of Health of outbreak-prone countries, the World Health Organization, Médecins Sans Frontières, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—Atlanta, and others. Keywords: Ebola; ebolavirus; Marburg virus; marburgvirus; Filoviridae; filovirus; outbreak; preparedness; response; data collection; treatment; guidelines; surveillance 1. Introduction Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Marburg virus disease (MVD) in human and non-human primates (NHPs) are caused by seven distinct viruses that produce filamentous, enveloped particles with negative-sense, single-stranded ribonucleic acid genomes. These viruses belong to the Filoviridae family and its Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus genera, respectively [1]. An eighth filovirus, Lloviu virus (LLOV), assigned to the third filovirus genus, Cuevavirus has thus far not been associated with human disease [2,3]. -

Uganda 2015 Human Rights Report

UGANDA 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Uganda is a constitutional republic led since 1986 by President Yoweri Museveni of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party. Voters re-elected Museveni to a fourth five-year term and returned an NRM majority to the unicameral Parliament in 2011. While the election marked an improvement over previous elections, it was marred by irregularities. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces. The three most serious human rights problems in the country included: lack of respect for the integrity of the person (unlawful killings, torture, and other abuse of suspects and detainees); restrictions on civil liberties (freedoms of assembly, expression, the media, and association); and violence and discrimination against marginalized groups, such as women (sexual and gender-based violence), children (sexual abuse and ritual killing), persons with disabilities, and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) community. Other human rights problems included harsh prison conditions, arbitrary and politically motivated arrest and detention, lengthy pretrial detention, restrictions on the right to a fair trial, official corruption, societal or mob violence, trafficking in persons, and child labor. Although the government occasionally took steps to punish officials who committed abuses, whether in the security services or elsewhere, impunity was a problem. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life There were several reports the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. On September 8, media reported security forces in Apaa Parish in the north shot and killed five persons during a land dispute over the government’s border demarcation. -

Download PDF (7.2

109 The *efrence l.simr/E íUganda Gazettej| Published 23rd March, 2007 Price: Shs. 1000 General Notice No. 122 of 2007. CONTENTS Page The Mining Act—Notices 109 THE ADVOCATES ACT. 109 The Advocates Act—Notices ... NOTICE. 110 The Companies Act—Notices ... The Electoral Commission Act—Notices 110-133 APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE OF ELIGIBILITY. 134 Sm ila Security Services Ltd— Notice It is hereby notified that an application has been 134-136 The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications presented to the Law Council by Nakibuule Madinah who is 136-138 Advertisements stated to be a holder of Bachelor of Laws of Makerere University having been awarded a Degree on the 22nd day SUPPLEMENT of October, 2004 and to have been awarded a Diploma in Legal Practice by the Law Development Centre on the 16th Legal Notice day of June, 2006 for the issue of a Certificate of Eligibility No. 2—The Universities and Other Tertiary Institutions Act for entry of her name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. (Publication of Particulars of a Private Tertiary Institution issued with Provisional Licence) (No. 2) Kampala. STELLA NYANDRIA, Notice. 2007. 21st March. 2007. for Acting Secretary, Law Council. General Notice No. 120 of 2007. THE MINING ACT. 2003 General Notice No. 123 of 2007. (The Mining Regulations, 2004) THE ADVOCATES ACT. NOTICE OF GRANT OF AN EXPLORATION LICENCE NOTICE. It is hereby notified that an Exploration Licence, number EL 0166 registered as number 0001168 has been APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE OF ELIGIBILITY. granted in accordance with the provisions of Section 27 and It is hereby notified that an application has been Section 29 to Glory Ministries International Community presented to the Law Council by Ntaro Nyeko Joseph who Foundation (U) Ltd of P.O. -

Vote:517 Kamuli District Quarter2

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2020/21 Vote:517 Kamuli District Quarter2 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 2 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:517 Kamuli District for FY 2020/21. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Date: 11/02/2021 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2020/21 Vote:517 Kamuli District Quarter2 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 545,891 373,486 68% Discretionary Government 4,425,320 2,335,957 53% Transfers Conditional Government Transfers 38,103,649 18,539,523 49% Other Government Transfers 1,995,208 612,466 31% External Financing 1,314,664 604,003 46% Total Revenues shares 46,384,732 22,465,434 48% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Administration 5,566,664 2,817,313 2,271,323 51% 41% 81% Finance 500,261 242,532 192,277 48% 38% 79% Statutory Bodies 915,404 477,769 413,546 52% 45% 87% Production and Marketing 1,755,678 882,304 663,561 50% 38% 75% Health 9,769,288 4,987,922 4,043,308 51% 41% 81% Education 22,602,810 10,376,662 8,850,508 46% 39% 85% -

Long-Term Storage of Sweetpotato by Small-Scale Farmers Through Improved Post Harvest Technologies

Uganda Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2004, 9: 914-922 ISSN 1026-0919 Printed in Uganda. All rights reserved. © 2004 National Agricultural Research Organisation Long-term storage of sweetpotato by small-scale farmers through improved post harvest technologies A. Namutebi, H. Natabirwa1, B Lemaga3, R. Kapinga2, M. Matovu1, S. Tumwegamire2, J. Nsumba3 and J.Ocom Department of Food Science & Technology, Makerere University, PO Box 7062, Kampala, Uganda 1Food Science and Technology Research Institute, P. O. Box 7852 Kampala, Uganda 2International Potato Centre, Regional Office, PO Box 22274, Kampala, Uganda 3The Regional Network for the Improvement of Potato and Sweet potato in East and Central Africa, PO Box 22274, Kampala, Uganda Abstract Sweetpotato (SP) small-scale farmers of Luweero and Mpigi districts were introduced to improved long-term storage methods (pit and clamp) as a way of improving their livelihood. Based on a participatory approach, farmers were involved in a storage study where dry matter, beta-carotene and sugar content parameters were monitored over a 60 day period in Mpigi and 75 days in Luweero district. Pit and clamp stores were constructed by farmers in selected sites of each district. Improved SP varieties (Ejumula, Naspot 1, Naspot 2, New Kawogo, Semanda and SPK004) were used for the storage study. Dry matter contents of SP were exceptionally high, particularly for roots from Mpigi district, with Semanda variety having the highest dry matter (41%). High beta-carotene concentrations were recorded for the orange-fleshed varieties, SPK004 and Ejumula, 68 and 125 mg/100 g, respectively. Total sugar contents of the roots were generally low (1.6-3.7 g/100 g), with exception of Naspot 2 (5.7 g/100 g). -

Sustaining the Bee Keeping Program at Namasagali College in Kamuli

Sustaining the Bee Keeping Program at Namasagali College in Kamuli, Uganda Brooklyn Snyder1, Blake Lineweaver2, Mika Rugaramna3, and Grace Nabulo4, 1, 2Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa, USA 3, 4Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Introduction Results Beekeeping, in the Kamuli district of Uganda, is used . Reestablished original hives according to cultural as an agricultural practice so that the people of and educational influencers Kamuli can be supported by not only the monetary . Established a log book for pupils to ensure value that honey as an entrepreneurial product gives productivity but also the sustainable practice in which consuming . Trained pupils to ensure effective habitat honey provides great nutritional and medicinal maintenance benefits. Manipulated surrounding habitat to be more attractive for colonies . The apiary is located within the secondary school Photo 2). Supported top bar hive Photo 3). Supported log hive . Relocated hives to cover a wider range of space at of Namasagali College where the entrepreneurship Namasagali College near plant species conducive club has direct access to be able to practice hands- Methods for colonization on learning skills concerning agriculture, the . Bated unoccupied hives with cow dung ecosystem, and business management . Created a pulley system for the hives . Encourages a diverse, functional habitat for native . Contacted local farmers Conclusions organisms . Trained members of the entrepreneurial club for . Beekeeping provides essential ecosystem benefits effective habitat maintenance for other organisms and the community . Implemented sunflower plots . Honey is an agricultural product that provides . Identified surrounding plant species reliable income . Cleared invasive and unwanted brush . Education is necessary for innovation . Created a log book for pupils . -

Vote:017 Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development

Vote Performance Report Financial Year 2018/19 Vote:017 Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development QUARTER 1: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget by End Q1 by End Q 1 End Q1 Released Spent Spent Recurrent Wage 6.225 1.556 1.556 1.152 25.0% 18.5% 74.1% Non Wage 85.788 16.876 16.876 15.937 19.7% 18.6% 94.4% Devt. GoU 325.227 165.045 165.045 139.862 50.7% 43.0% 84.7% Ext. Fin. 1,339.221 258.273 258.273 360.077 19.3% 26.9% 139.4% GoU Total 417.240 183.477 183.477 156.952 44.0% 37.6% 85.5% Total GoU+Ext Fin 1,756.460 441.750 441.750 517.029 25.1% 29.4% 117.0% (MTEF) Arrears 0.242 0.173 0.173 0.000 71.4% 0.0% 0.0% Total Budget 1,756.702 441.922 441.922 517.029 25.2% 29.4% 117.0% A.I.A Total 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Grand Total 1,756.702 441.922 441.922 517.029 25.2% 29.4% 117.0% Total Vote Budget 1,756.460 441.750 441.750 517.029 25.1% 29.4% 117.0% Excluding Arrears Table V1.2: Releases and Expenditure by Program* Billion Uganda Shillings Approved Released Spent % Budget % Budget %Releases Budget Released Spent Spent Program: 0301 Energy Planning,Management & 890.50 253.99 214.55 28.5% 24.1% 84.5% Infrastructure Dev't Program: 0302 Large Hydro power infrastructure 751.03 145.75 285.22 19.4% 38.0% 195.7% Program: 0303 Petroleum Exploration, Development, 57.93 22.14 6.98 38.2% 12.0% 31.5% Production, Value Addition and Distribution and Petrolleum Products Program: -

Local Government Quarter 2 Expenditure Limits by Vote and Item

Unconditional Grant Non- Support Services Conditional Grant (Non-wage) Pension and wage Conditional IFMS IPPS Boards and Commisions PAF Monitoring and Accountability DSC EX Gratia and Hard to Reach Pension for Gratuity for Vote Local Government District Grant (Non- Recurrent Recurrent Operational Councillors' Allowances Teachers Local Component wage) Total Costs Costs Normal PRDP Total Normal PRDP Total costs allowances Governments 321469 o/w o/w o/w o/w o/w o/w 212103 212105 321401 501 Adjumani District 70,333 7,500 - 7,030 16,965 23,995 9,614 9,455 19,069 6,569 13,200 357,364 42,075 172,271 112,092 502 Apac District 70,438 7,500 - 7,030 5,902 12,932 17,234 6,313 23,547 11,758 14,700 - 328,001 763,115 164,460 503 Arua District 110,298 7,500 - 7,030 15,105 22,135 26,551 10,070 36,621 25,592 18,450 - 452,432 345,212 356,989 504 Bugiri District 50,557 7,500 - 7,030 - 7,030 12,143 - 12,143 9,933 13,950 4,171 71,372 385,066 155,982 505 Bundibugyo District 48,218 7,500 - 7,030 - 7,030 9,657 - 9,657 7,830 16,200 411,325 46,975 270,173 88,150 506 Bushenyi District 61,908 11,786 6,250 7,030 - 7,030 10,543 - 10,543 12,349 13,950 - - 88,534 222,435 507 Busia District 59,123 7,500 - 7,030 - 7,030 10,280 4,808 15,088 10,305 19,200 - 110,077 155,353 128,289 508 Gulu District 88,745 7,500 - 7,030 9,501 16,532 18,027 9,501 27,529 16,485 20,700 882,273 342,820 255,276 168,801 509 Hoima District 52,515 - - 7,030 - 7,030 14,124 - 14,124 12,162 19,200 - 627,237 136,974 214,390 510 Iganga District 71,706 7,500 - 7,030 - 7,030 19,245 - 19,245 19,480 18,450 -

Challenges of Development and Natural Resource Governance In

Ian Karusigarira Uganda’s revolutionary memory, victimhood and regime survival The road that the community expects to take in each generation is inspired and shaped by its memories of former heroic ages —Smith, D.A. (2009) Ian Karusigarira PhD Candidate, Graduate School of Global Studies, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Japan Abstract In revolutionary political systems—such as Uganda’s—lies a strong collective memory that organizes and enforces national identity as a cultural property. National identity nurtured by the nexus between lived representations and narratives on collective memory of war, therefore, presents itself as a kind of politics with repetitive series of nation-state narratives, metaphorically suggesting how the putative qualities of the nation’s past reinforce the qualities of the present. This has two implications; it on one hand allows for changes in a narrative's cognitive claims which form core of its constitutive assumptions about the nation’s past. This past is collectively viewed as a fight against profanity and restoration of political sanctity; On the other hand, it subjects memory to new scientific heuristics involving its interpretations, transformation and distribution. I seek to interrogate the intricate memory entanglement in gaining and consolidating political power in Uganda. Of great importance are politics of remembering, forgetting and utter repudiation of memory of war while asserting control and restraint over who governs. The purpose of this paper is to understand and internalize the dynamics of how knowledge of the past relates with the present. This gives a precise definition of power in revolutionary-dominated regimes. Keywords: Memory of War, national narratives, victimhood, regime survival, Uganda ―75― 本稿の著作権は著者が保持し、クリエイティブ・コモンズ表示4.0国際ライセンス(CC-BY)下に提供します。 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja Uganda’s revolutionary memory, victimhood and regime survival 1. -

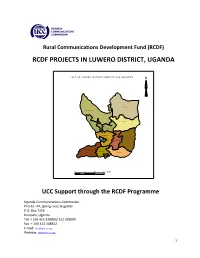

Rcdf Projects in Luwero District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN LUWERO DISTRICT, UGANDA MA P O F L UW E R O D IS T R IC T S H O W IN G S U B C O U N T IE S N Kam ira Butu ntu m ula Kiky us a Luw e ro TC Luwe ro Katik am u Zirobwe W ob ule nz i T C Bam una nika M ak ulubita N yim bw a Kalaga la Bom bo TC 10 0 10 20 Km s UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....….…3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……...……4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….…….……..4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Luwero district………..…….…….….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Luwero district………..………………….………..…...…….14 10- Map of Luwero district showing sub counties………..……………..……………….15 11- Table showing the population of Luwero district by sub counties…………..15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Luwero district…………………………………….……………16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. -

Experiences of Women War-Torture Survivors in Uganda: Implications for Health and Human Rights Helen Liebling-Kalifani

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 8 | Issue 4 Article 1 May-2007 Experiences of Women War-Torture Survivors in Uganda: Implications for Health and Human Rights Helen Liebling-Kalifani Angela Marshall Ruth Ojiambo-Ochieng Nassozi Margaret Kakembo Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Liebling-Kalifani, Helen; Marshall, Angela; Ojiambo-Ochieng, Ruth; and Kakembo, Nassozi Margaret (2007). Experiences of Women War-Torture Survivors in Uganda: Implications for Health and Human Rights. Journal of International Women's Studies, 8(4), 1-17. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol8/iss4/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2007 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Experiences of Women War-Torture Survivors in Uganda: Implications for Health and Human Rights By Helen Liebling-Kalifani,1 Angela Marshall,2 Ruth Ojiambo-Ochieng,3 and Nassozi Margaret Kakembo4 The effect of the aggressive rapes left me with constant chest, back and abdominal pain. I get some treatment but still, from time to time it starts all over again. It was terrible (Woman discussing the effects of civil war during a Kamuli Parish focus group). Amongst the issues treated as private matters that cannot be regulated by international norms, violence against women and women‟s health are particularly critical. -

Kamuli District Local Government Performance Assessment Report

Local Government Performance Assessment Kamuli District (Vote Code: 517) Assessment Scores Accountability Requirements 83% Crosscutting Performance Measures 59% Educational Performance Measures 68% Health Performance Measures 65% Water Performance Measures 75% 517 Kamuli District Accountability Requirements 2019 Summary of requirements Definition of compliance Compliance justification Compliant? Annual performance contract Yes LG has submitted an annual performance • From MoFPED’s The Annual Performance Contract for the contract of the forthcoming year by June 30 on inventory/schedule of LG forthcoming year 2020/21 was submitted the basis of the PFMAA and LG Budget submissions of performance on 17thJuly, 2019 and thus adhered to guidelines for the coming financial year. contracts, check dates of the adjusted submission date of submission and issuance of 31stAugust, 2019. receipts and: o If LG submitted before or by due date, then state ‘compliant’ o If LG had not submitted or submitted later than the due date, state ‘non- compliant’ • From the Uganda budget website: www.budget.go.ug, check and compare recorded date therein with date of LG submission to confirm. Supporting Documents for the Budget required as per the PFMA are submitted and available Yes LG has submitted a Budget that includes a • From MoFPED’s inventory Kamuli LG submitted the approved Procurement Plan for the forthcoming FY by of LG budget submissions, Budget Estimates that included a 30th June (LG PPDA Regulations, 2006). check whether: Procurement Plan for the FY 2019/20 on 17thJuly, 2019 thus being within the o The LG budget is adjusted submission date of 31st August, accompanied by a 2019. Procurement Plan or not.