Can India Give up Kashmir: an Option Or a Risk?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

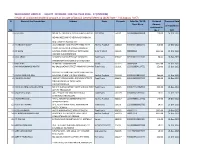

(INTERIM) Details of Unclaimed Dividend Amount As On

WOCKHARDT LIMITED - EQUITY DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2016 - 17 (INTERIM) Details of unclaimed dividend amount as on date of Annual General Meeting (AGM Date - 2nd August, 2017) SI Name of the Shareholder Address State Pin code Folio No / DP ID Dividend Proposed Date Client ID no. Amount of Transfer to unclaimed in No. (Rs.) IEPF 1 A G SUJAY NO 49 1ST MAIN 4TH CROSS HEALTH LAYOUT Karnataka 560091 1203600000360918 120.00 16-Dec-2023 VISHWANEEDAM PO NEAR NAGARABHAVI BDA COMPLEX BANGALORE 2 A HANUMA REDDY 302 HARBOUR HEIGHTS OPP PANCHAYAT Andhra Pradesh 524344 IN30048418660271 510.00 16-Dec-2023 OFFICE MUTHUKUR ANDHRA PRADESH 3 A K GARG C/O M/S ANAND SWAROOP FATEHGANJ Uttar Pradesh 203001 W0000966 3000.00 16-Dec-2023 [MANDI] BULUNDSHAHAR 4 A KALARANI 37 A(NEW NO 50) EZHAVAR SANNATHI Tamil Nadu 629002 IN30108022510940 50.00 16-Dec-2023 STREET KOTTAR NAGERCOIL,TAMILNADU 5 A M LAZAR ALAMIPALLY KANHANGAD Kerala 671315 W0029284 6000.00 16-Dec-2023 6 A M NARASIMMABHARATHI NO 140/3 BAZAAR STREET AMMIYARKUPPAM Tamil Nadu 631301 1203320004114751 250.00 16-Dec-2023 PALLIPET-TK THIRUVALLUR DT THIRUVALLUR 7 A MALLIKARJUNA RAO DOOR NO 1/1814 Y M PALLI KADAPA Andhra Pradesh 516004 IN30232410966260 500.00 16-Dec-2023 8 A NABESA MUNAF 46B/10 THIRUMANJANA GOPURAM STREET Tamil Nadu 606601 IN30108022007302 600.00 16-Dec-2023 TIRUVANNAMALAI TAMILNADU TIRUVANNAMALAI 9 A RAJA SHANMUGASUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST Tamil Nadu 614625 IN30177414782892 250.00 16-Dec-2023 AND TK THANJAVUR 10 A RAJESH KUMAR 445-2 PHASE 3 NETHAJI BOSE ROAD Tamil Nadu 632009 -

Consanguinity and Its Sociodemographic Differentials in Bhimber District, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan

J HEALTH POPUL NUTR 2014 Jun;32(2):301-313 ©INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR DIARRHOEAL ISSN 1606-0997 | $ 5.00+0.20 DISEASE RESEARCH, BANGLADESH Consanguinity and Its Sociodemographic Differentials in Bhimber District, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan Nazish Jabeen, Sajid Malik Human Genetics Program, Department of Animal Sciences, Quaid-i-Azam University, 45320 Islamabad, Pakistan ABSTRACT Kashmiri population in the northeast of Pakistan has strong historical, cultural and linguistic affini- ties with the neighbouring populations of upper Punjab and Potohar region of Pakistan. However, the study of consanguineous unions, which are customarily practised in many populations of Pakistan, revealed marked differences between the Kashmiris and other populations of northern Pakistan with respect to the distribution of marriage types and inbreeding coefficient (F). The current descriptive epidemiological study carried out in Bhimber district of Mirpur division, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan, demonstrated that consanguineous marriages were 62% of the total marriages (F=0.0348). First-cousin unions were the predominant type of marriages and constituted 50.13% of total marital unions. The estimates of inbreeding coefficient were higher in the literate subjects, and consanguinity was witnessed to be rising with increasing literacy level. Additionally, consanguinity was observed to be associated with ethnicity, family structure, language, and marriage arrangements. Based upon these data, a distinct sociobiological structure, with increased stratification and higher genomic homozygos- ity, is expected for this Kashmiri population. In this communication, we present detailed distribution of the types of marital unions and the incidences of consanguinity and inbreeding coefficient (F) across various sociodemographic strata of Bhimber/Mirpuri population. The results of this study would have implication not only for other endogamous populations of Pakistan but also for the sizeable Kashmiri community immigrated to Europe. -

A Pilgrim's Diary to Badri, Jyoshi Mutt Etc Visited and Penned by Sri

A Pilgrim’s diary to Badri, Jyoshi mutt etc Visited and penned by Sri Varadan NAMO NARAYANAYA SRIMAN NARAYANAYA CHARANAU SARANAM PRAPATHYE SRIMATHEY NARAYANAYAH NAMAH SRI ARAVINDAVALLI NAYIKA SAMETHA SRI BADRINARAYANAYA NAMAH SRI PUNDARIKAVALLI NAYIKA SAMETHA SRI PURUSHOTHAMAYA NAMAH SRI PARIMALAVALLI NAYIKA SAMETHA SRI PARAMPURUSHAYA NAMAH SRIMATHE RAMANUJAYA NAMAH Due to the grace of the Divya Dampadhigal and Acharyar, Adiyen was blessed to visit Thiru Badrinath and other divya desams enroute during October,2003 along with my family. After returning from Badrinath, Adiyen also visited Tirumala-Tirupati and participated in Vimsathi darshanam a scheme which allows a family of 6 members to have Suprabatham, Nijapada and SahasraDeepalankara seva for any 2 consecutive days in a year . It was only due to the abundant grace of Thiruvengadamudaiyan adiyen was able to vist all the Divya desams without any difficulty. Before proceeding further, Adiyen would like to thank all the internet bhagavathas especially Sri Rangasri group members and M.S.Ramesh for providing abundant information about these divya desams. I have uploaded a Map of the hills again downloaded from UP Tourism site for ready reference . As Adiyen had not planned the trip in advance, it was not possible to join “package tour” organised by number of travel agencies and could not do as it was Off season. Adiyen wishes to share my experience with all of you and request the bhagavathas to correct the shortcomings. Adiyen was blessed to take my father aged about 70 years a heart patient , to this divya desam and it would not be an exaggeration to say that only because of my acharyar’s and elders’ blessings , the trip was very comfortable. -

Khalistan & Kashmir: a Tale of Two Conflicts

123 Matthew Webb: Khalistan & Kashmir Khalistan & Kashmir: A Tale of Two Conflicts Matthew J. Webb Petroleum Institute _______________________________________________________________ While sharing many similarities in origin and tactics, separatist insurgencies in the Indian states of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir have followed remarkably different trajectories. Whereas Punjab has largely returned to normalcy and been successfully re-integrated into India’s political and economic framework, in Kashmir diminished levels of violence mask a deep-seated antipathy to Indian rule. Through a comparison of the socio- economic and political realities that have shaped the both regions, this paper attempts to identify the primary reasons behind the very different paths that politics has taken in each state. Employing a distinction from the normative literature, the paper argues that mobilization behind a separatist agenda can be attributed to a range of factors broadly categorized as either ‘push’ or ‘pull’. Whereas Sikh separatism is best attributed to factors that mostly fall into the latter category in the form of economic self-interest, the Kashmiri independence movement is more motivated by ‘push’ factors centered on considerations of remedial justice. This difference, in addition to the ethnic distance between Kashmiri Muslims and mainstream Indian (Hindu) society, explains why the politics of separatism continues in Kashmir, but not Punjab. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Of the many separatist insurgencies India has faced since independence, those in the states of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir have proven the most destructive and potent threats to the country’s territorial integrity. Ostensibly separate movements, the campaigns for Khalistan and an independent Kashmir nonetheless shared numerous similarities in origin and tactics, and for a brief time were contemporaneous. -

2. Detail of Land Looser Appointments

F.No District Name of land owner Claimant for job Remarks S.No 1 1 Baramulla Ab Jabar Mir Tahir Jabbar Appointment given 2 2 Baramulla Habir Dar Tariq Ahmed Dar Appointment given 3 3 Baramulla Ab Qayoom Kimani Ummul Mudal Appointment given 4 4 Baramulla Ahad S/o Khalil Tantray Hilal Ahmed Appointment given 5 5 Baramulla Sharief-u-dine Mudasir Sharief Appointment given 6 Baramulla Sirajudin,ShaffudunBashir Umar Bashir s/o Appointment given 6 Ahmed etc. Bashir Ahmad 7 7 Baramulla Bashir Ahmed Javid Ahmad Appointment given 8 8 Baramulla Bashir Ah. Naikoo Tahira Bashir Appointment given 9 10 Baramulla Gh Qadir Guroo Hilal Ahmed Appointment given 10 11 Baramulla Mohmud Md. Yousuf Appointment given 11 12 Baramulla Gh Mohd. Bashir Ah.Ganie Appointment given 12 14 Baramulla Gh Ahmed Tantary Ab. Hamid Tantry Appointment given 23 Baramulla Ramzan Manzoor Ahmed Appointment given 13 Rather 27 Baramulla Jawahar Lal Dhar S/O Sahil Dhar Appointment given 14 Mahesh Nath 15 36 Pulwama Ab Hamid Dar Adil Hamid Dar Appointment given 16 38 Pulwama Subhan Jahangir Ahmed Appointment given 39 Pulwama Gh Nabi S/o Lassa Lone Shabir Ahmad Lone Appointment given 17 18 40 Pulwama Gh Ahmad Nisar Ahmed Appointment given 19 42 Pulwama Gh. Nabi Bhat Shabir Ahmad Bhat Appointment given 20 43 Pulwama Shaban Riyaz Ahmad Dar Appointment given 21 45 Pulwama Bashir Ah. Ganie Bashir Ah. Ganie Appointment given 22 46 Pulwama Gh Hassan Dar Zahoor Ahmed Dar Appointment given 47 Pulwama Jameela Akther Kurshid Ahmad Appointment given 23 Kuchay 24 48 Pulwama Gh Hassan Sheikh Tawseef Hassan Appointment given 25 49 Pulwama Md Abdullah Sheikh Mehraj-u-Din Appointment given 26 50 Pulwama Aziz Mir S/o Samad Mir Gulzar Ahmed Appointment given 27 51 Pulwama Rehman Hajam Ab. -

India, Pakistan and the Kashmir Dispute Asian Studies Institute & Centre for Strategic Studies Rajat Ganguly ISSN: 11745991 ISBN: 0475110552

Asian Studies Institute Victoria University of Wellington 610 von Zedlitz Building Kelburn, Wellington 04 463 5098 [email protected] www.vuw.ac.nz/asianstudies India, Pakistan and the Kashmir Dispute Asian Studies Institute & Centre for Strategic Studies Rajat Ganguly ISSN: 11745991 ISBN: 0475110552 Abstract The root cause of instability and hostility in South Asia stems from the unresolved nature of the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan. It has led to two major wars and several near misses in the past. Since the early 1990s, a 'proxy war' has developed between India and Pakistan over Kashmir. The onset of the proxy war has brought bilateral relations between the two states to its nadir and contributed directly to the overt nuclearisation of South Asia in 1998. It has further undermined the prospects for regional integration and raised fears of a deadly IndoPakistan nuclear exchange in the future. Resolving the Kashmir dispute has thus never acquired more urgency than it has today. This paper analyses the origins of the Kashmir dispute, its influence on IndoPakistan relations, and the prospects for its resolution. Introduction The root cause of instability and hostility in South Asia stems from the unresolved nature of the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan. In the past fifty years, the two sides have fought three conventional wars (two directly over Kashmir) and came close to war on several occasions. For the past ten years, they have been locked in a 'proxy war' in Kashmir which shows little signs of abatement. It has already claimed over 10,000 lives and perhaps irreparably ruined the 'Paradise on Earth'. -

Pt. Bansi Dhar Nehru Was Born in 1843 at Delhi

The firm foundation of the Mughal empire in India was laid by a Uzbek Mongol warrior Zahiruddin Mohammand Babar, who was born in 1483 in a tiny village Andijan on the border of Uzbekistan and Krigistan after defeating the Sultan of Delhi Ibrahim Lodi in the battle of Panipat which took place in 1526, The Rajputs soon thereafter under the command of Rana Sanga challenged the authority of Babar, but were badly routed in the battle of Khanwa near Agra on 16th March, 1527. Babar with a big army then went upto Bihar to crush the revolt of Afgan chieftains and on the way his commander in chief Mir Baqi destroyed the ancient Ram Temple at Ayodhya and built a mosque at that spot in 1528. Babar than returned back to Agra where he died on 26th December 1530 dur t o injuries received in the battle with Afgans in 1529 at the Ghaghra’s is basin in Bihar. After Babar’s death his son Nasiruddin Humanyu ascended the throne, but he had to fight relentless battels with various rebellious chieftains for fight long years. The disgruntled Afghan chieftains found Sher Shah Suri as an able commander who defeated Humanyu in the battle of Chausa in Bihar and assumed power at Delhi in 1543. Sher Shah Suri died on 22nd May 1545 due to injuries suffered in a blast after which the Afghan power disintegrated. Hymanyu then taking full advantage of this fluid political situation again came back to India with reinforcements from Iran and reoccupied the throne at Delhi after defeating Adil Shah in the second battle of Panipat in 1555. -

Kashmir Conflict: a Critical Analysis

Society & Change Vol. VI, No. 3, July-September 2012 ISSN :1997-1052 (Print), 227-202X (Online) Kashmir Conflict: A Critical Analysis Saifuddin Ahmed1 Anurug Chakma2 Abstract The conflict between India and Pakistan over Kashmir which is considered as the major obstacle in promoting regional integration as well as in bringing peace in South Asia is one of the most intractable and long-standing conflicts in the world. The conflict originated in 1947 along with the emergence of India and Pakistan as two separate independent states based on the ‘Two-Nations’ theory. Scholarly literature has found out many factors that have contributed to cause and escalate the conflict and also to make protracted in nature. Five armed conflicts have taken place over the Kashmir. The implications of this protracted conflict are very far-reaching. Thousands of peoples have become uprooted; more than 60,000 people have died; thousands of women have lost their beloved husbands; nuclear arms race has geared up; insecurity has increased; in spite of huge destruction and war like situation the possibility of negotiation and compromise is still absence . This paper is an attempt to analyze the causes and consequences of Kashmir conflict as well as its security implications in South Asia. Introduction Jahangir writes: “Kashmir is a garden of eternal spring, a delightful flower-bed and a heart-expanding heritage for dervishes. Its pleasant meads and enchanting cascades are beyond all description. There are running streams and fountains beyond count. Wherever the eye -

"Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland

"Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland Author(s): Haley Duschinski Source: International Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1 (Apr., 2008), pp. 41-64 Published by: Springer Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40343840 Accessed: 12-01-2020 07:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal of Hindu Studies This content downloaded from 134.114.107.39 on Sun, 12 Jan 2020 07:34:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland Haley Duschinski Kashmiri Hindus are a numerically small yet historically privileged cultural and religious community in the Muslim- majority region of Kashmir Valley in Jammu and Kashmir State in India. They all belong to the same caste of Sarasvat Brahmanas known as Pandits. In 1989-90, the majority of Kashmiri Hindus living in Kashmir Valley fled their homes at the onset of conflict in the region, resettling in towns and cities throughout India while awaiting an opportunity to return to their homeland. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

History, University of Kashmir

Post Graduate Department of History University of Kashmir Syllabus For the Subject History At Under-Graduate Level Under Semester System (CBCS) Effective from Academic Session 2016 Page 1 of 16 COURSE CODE COURSE TITLE SEMESTER CORE PAPERS CR-HS-I ANCIENT INDIA/ANCIENT FIRST KASHMIR CR-HS-II MEDIEVAL SECOND INDIA/MEDIEVAL KASHMIR CR-HS-III MODERN INDIA/MODERN THIRD KASHMIR CR-HS-IV THEMES IN INDIAN FOURTH ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY DISCIPLINE SPECIFIC ELECTIVES DSE-HS-I HISTORY OF INDIA SINCE FIFTH 1947 DSE-HS-II HISTORY OF THE WORLD FIFTH (1945-1992) DSE-HS-III THEMES IN WORLD SIXTH CIVILIZATION DSE-HS-IV WOMEN IN INDIAN SIXTH HISTORY GENERIC ELECTIVES GE-HS-I (THEMES IN HISTORY-I) FIFTH GE-HS-II (THEMES IN HISTORY – II) SIXTH SKILL ENHANCEMENT COURSES SEC-HS-I ARCHAEOLOGY: AN THIRD INTRODUCTION SEC-HS-II HERITAGE AND TOURISM FOURTH IN KASHMIR SEC-HS-III ARCHITECTURE OF FIFTH KASHMIR SEC-HS-IV ORAL HISTORY: AN SIXTH INTRODUCTION Page 2 of 16 CR-HS-I (ANCIENT INDIA/ANCIENT KASHMIR) UNIT-I (Pre and Proto History) a) Sources] i. Archaeological Sources: Epigraphy and Numismatics ii. Literary Sources: Religious, Secular and Foreign Accounts b. Pre and Proto History: Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic Cultures: Features. c. Chalcolithic Cultures: Features d. Harappan Civilization: Emergence, Features, Decline, Debate. UNIT-II (From Vedic to Mauryas) a) Vedic Age i. Early Vedic Age: Polity, Society. ii. Later-Vedic Age: Changes and Continuities in Polity and Society. b) Second Urbanization: Causes. c) Janapadas, Mahajanapadas and the Rise of Magadh. d) Mauryas: Empire Building, Administration, Architecture; Decline of the Mauryan Empire (Debate). -

Khir Bhawani Temple

Khir Bhawani Temple PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Kashmir: The Places of Worship Page Intentionally Left Blank ii KASHMIR NEWS NETWORK (KNN)). PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Kashmir: The Places of Worship KKaasshhmmiirr:: TThhee PPllaacceess ooff WWoorrsshhiipp First Edition, August 2002 KASHMIR NEWS NETWORK (KNN)) iii PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Kashmir: The Places of Worship Contents page Contents......................................................................................................................................v 1 Introduction......................................................................................................................1-2 2 Some Marvels of Kashmir................................................................................................2-3 2.1 The Holy Spring At Tullamulla ( Kheir Bhawani )....................................................2-3 2.2 The Cave At Beerwa................................................................................................2-4 2.3 Shankerun Pal or Boulder of Lord Shiva...................................................................2-5 2.4 Budbrari Or Beda Devi Spring..................................................................................2-5 2.5 The Chinar of Prayag................................................................................................2-6