A State of One's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Origin and Development of the Meitei Language

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Modern Education (IJMRME) ISSN (Online): 2454 - 6119 (www.rdmodernresearch.org) Volume II, Issue I, 2016 ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE MEITEI LANGUAGE Khongbantabam Naobi Devi Ph.D Scholar, Department of English, Ethiraj College for Women, Chennai, Tamilnadu Abstract: Meitei language is an Indo-Aryan language. The Indo- Aryans came to Manipur and settled in the Manipur from the 4th century B.C. onwards. The noted historian and scholar R.K. Jhalajit Singh present his views on the topic to Dr. Suniti Kumar Chatterjee, the great scholar and experts on language. He expressed as Meitei language may not belong to the Kuki- Chin sub-group of the Tibeto-Burman branch; but belongs to the Sino-Tibetan family of language. All the language that belongs to the Tibeto-Burman, a sub-branch of the Sino- Tibetan family of languages, is mono- syllabic. The Meiteis language is not a monosyllabic language; it is a polysyllabic language. In meiteis language, majority of words have more than one syllable. A language should be classified because of grammar. This is the universal principle accepted on all. A language cannot be classified according to vocabulary. If we begin to classify a language according to its vocabulary, the results will be incorrect. The first settlers of the Indo-Aryans in Manipur spoke Sanskrit. Later settlers spoke Prakrit. When Prakrit was removed as spoken language, they spoke Apabhransha.. The combination of Apabhransha and Mongoloid languages gave birth to the Manipuri language by about 1074 A.D. In the olden days of the Meitei language, which was formed by the interaction of Apabhransha and Mongoloid languages, the most important words were taken from Sanskrit. -

UNICEF Support to the COVID-19 Surge in India As Part of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A)

UNICEF support to the COVID-19 surge in India as part of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) The reach and capacity of the cold chain system in India is strengthened to sustain the massive COVID- 19 vaccine drive • UNICEF has worked at the request of MoHFW to augment the cold chain network across the country since third quarter of 2020. In preparation of the launch of vaccination drive, additional cold chain equipment, such as a Walk-In Cold Rooms (WIC), Walk-In Freezer Rooms (WIF), fridges and deep freezers were procured to enhance vaccine storage at all levels. Vaccine transportation passive devices (cold box/vaccine carriers) were also procured to support the vaccination rollout. • The vaccine rollout was launched nationwide on the 16th of January 2021, with priority to Health Care Workers, Frontline Workers and people aged 60 years and above. On 1st April 2021, vaccination was made available to those above the age of 45. Over 156 million vaccine doses have been administered as of 1st May 2021, Day 106 of the vaccination campaign, making India the country with the fastest vaccination scale up in the world. • As of May 1st, vaccine eligibility has been expanded to all above the age of 18. With this expansion and to support equitable access to vaccination even in remote areas, UNICEF will/ plans to further augment bulk storage sites by providing additional equipment (WIC/WIF) along with Solar Direct Drive (SDD) Fridges for remote locations with limited power supply. • Current COVID-19 vaccines in use in India are freeze sensitive. -

Annual Report 2016-17 Maharaja Martand Singh Judeo White Tiger

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17 MAHARAJA MARTAND SINGH JUDEO WHITE TIGER SAFARI & ZOO ABOUT ZOO: The Maharaja Martand Singh Judeo white tiger safari and zoo is located in the Mukundpur of Satna district of Rewa division. The zoo is 15 km far from Rewa and 55 km far from Satna. Rewa is a city in the north-eastern part of Madhya Pradesh state in India. It is the administrat ive centre of Rewa District and Rewa Division In nearby Sidhi district, a part of the erstwhile princely state of Rewa, and now a part of Rewa division, the world's first white tiger, “Mohan” a mutant variant of the Bengal tiger, was reported and captured. To bring the glory back and to create awareness for conservation, a white tiger safari and zoo is established in the region. Geographically it is one of the unique region where White Tiger was originally found. The overall habitat includes tall trees, shrubs, grasses and bushes with mosaic of various habitat types including woodland and grassland is an ideal site and zoo is developed amidst natural forest. It spreads in area of 100 hectare of undulating topography. The natural stream flows from middle of the zoo and the perennial river Beehad flows parallel to the northern boundary of the zoo. The natural forest with natural streams, rivers and water bodies not only makes the zoo aesthetically magnificent but also provides natural environment to the zoo inmates. The zoo was established in June 2015 and opened for the public in April 2016. VISION: The Zoo at Mukundpur will provide rewarding experience to the visitors not about the local wildlife but also of India. -

Imphal East Manipur |

DISTRICTDISTRICT NUTRITION NUTRITION PROFILE PROFILE Bi Imphal East|Manipur DISTRICT DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE1 5 Total Population 4,56,113 6 M0 Census 2011 Male Female 749.6%Fe1 Census 2011 50.4% 8 U # Census 2011 9UrbanRu1 Census 2011 Rural #40.2%SC0 Census 2011 59.8% # ST0 Census 2011 SC# O 1ST Census 2011 Others Imphal East ranks 141 amongst 599 3.5% # In6.1%#0 90.5% districts in India² THE STATE OF NUTRITION IN IMPHAL EAST UNDERNUTRITION3 100 Imphal East Manipur 75MImphal East # St ##NFHS4 50 %# W 78NFHS4 26.2 27.3 # U ##NFHS4 20.8 25 17.1 # An##NFHS4 7.8 NO DISTRICT LEVEL DATA 9.7 # Lo07#RSOC # An##NFHS4Stunting Wasting Underweight Anemia Low birth weight Anemia among Women with body (among children <5 (among children <5 (among children <5 (among children <5 (<2500 g) women of mass index <18.5 # W 9#NFHS4years) years) years) years) reproductive age kg/m2 # BMPOSSIBLE##NFHS4 POINTS OF DISCUSSION (WRA) # BM##NFHS4 How does the district perform on stunting, wasting, underweight and anemia among children under the age of 5? # H ##WhatNFHS4 are the levels of anemia prevalence and low body mass index among women? # H ##WhatNFHS4 are the levels of overweight/obesity and other nutrition-related non-communicable diseases in the district? # H 88NFHS4 OVERWEIGHT/OBESITY & NON-COMMUNICABLE DISEASES (15-49 y)4 # 100H 9#NFHS4 75 % 50 30.8 22.2 22.4 25 12 8 11.3 0 BMI >25 kg/m2 BMI >25 kg/m2 High blood pressure High blood pressure High blood sugar High blood sugar among women among men among women among men among women among men (15-49 years) (15-49 -

Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 an International Refereed/Peer-Reviewed English E-Journal Impact Factor: 4.727 (SJIF)

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed/Peer-reviewed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 4.727 (SJIF) Echoes of the Past: Revisiting Myths in T.S.Eliot’s The Waste Land GAURAB SENGUPTA M.Phil Research Scholar Department of English Dibrugarh University Dibrugarh, Assam. Abstract In The Waste Land (1922) T.S.Eliot presents the degraded, infected and corrupted view of modern day London. In the modern day, humanity has lost its faith in religion, in spirituality as well as in other humans. Eliot continuously tries to compare the present situations with the past just to show us that it is not only the present day Europe which is ailing or ill, but people have suffered the same loss even during the past. Since experiences in the modern day world are so complex therefore he compares the present with the past drawing using mythical methods and allusions from Greek and Roman myths, Christian and pre- Christian and pagan myths and rituals to show the decay of humanity in the present day. Eliot in the poem marvelously and skillfully juxtaposes the present with the past. And thus they comment on each other. This paper is an attempt to show how the past still echoes in the present with the images drawn from various civilizations. Keywords: degradation, modern, myth, past, present Introduction: “…the difference between the present and the past is that the conscious present is an awareness of the past in a way and to an extent the past‟s awareness of itself cannot show.” (Tradition and the Individual Talent. -

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (As on 20.11.2020)

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (as on 20.11.2020) Sl. Year of State District Block/ Taluka Village/ Habitation Name of the School Status No. sanction 1 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Y. Ramavaram P. Yerragonda EMRS Y Ramavaram 1998-99 Functional 2 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Kodavalur Kodavalur EMRS Kodavalur 2003-04 Functional 3 Andhra Pradesh Prakasam Dornala Dornala EMRS Dornala 2010-11 Functional 4 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Gudem Kotha Veedhi Gudem Kotha Veedhi EMRS GK Veedhi 2010-11 Functional 5 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor Buchinaidu Kandriga Kanamanambedu EMRS Kandriga 2014-15 Functional 6 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Maredumilli Maredumilli EMRS Maredumilli 2014-15 Functional 7 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Ozili Ojili EMRS Ozili 2014-15 Functional 8 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Meliaputti Meliaputti EMRS Meliaputti 2014-15 Functional 9 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Bhamini Bhamini EMRS Bhamini 2014-15 Functional 10 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Munchingi Puttu Munchingiputtu EMRS Munchigaput 2014-15 Functional 11 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Dumbriguda Dumbriguda EMRS Dumbriguda 2014-15 Functional 12 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Makkuva Panasabhadra EMRS Anasabhadra 2014-15 Functional 13 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Kurupam Kurupam EMRS Kurupam 2014-15 Functional 14 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Pachipenta Guruvinaidupeta EMRS Kotikapenta 2014-15 Functional 15 Andhra Pradesh West Godavari Buttayagudem Buttayagudem EMRS Buttayagudem 2018-19 Functional 16 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Chintur Kunduru EMRS Chintoor 2018-19 Functional -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

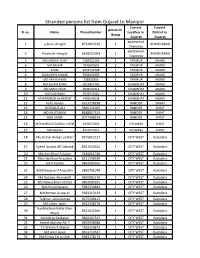

Stranded Persons List from Gujarat to Manipur Current Current Person in Sl No

Stranded persons list from Gujarat to Manipur Current Current person in Sl no. Name PhoneNumber Location in District in Group Gujarat Gujarat applewood 1 juliana shinglai 8732015246 1 AHMEDABAD Township applewood 2 Rinchuila shinglai 6358212054 1 AHMEDABAD Township 3 MOHADDAD SHAFI 7383021363 1 TARAPUR ANAND 4 MD BASHIR 7041660692 1 TARAPUR ANAND 5 AFZAL 9429745368 1 TARAPUR ANAND 6 SLIMUDDIN MAKAK 9366464969 1 TARAPUR ANAND 7 MD YAHYA KHAN 738302066 1 TARAPUR ANAND 8 MD ASLAM KHAN 9023861796 1 KHAMBHAT ANAND 9 MD SAROJ KHAN 6009130314 1 KHAMBHAT ANAND 10 MD SULEIMAN 9558737681 1 KHAMBHAT ANAND 11 MUHAMMED SHAHADAT 7486096838 1 KHAMBHAT ANAND 12 hafiz rizwan 6353278298 1 RANDER SURAT 13 SIDDIQUE ALI 9366171005 1 RANDER SURAT 14 MD MUSTAKIM 8488857313 1 RANDER SURAT 15 MM SARIF 9077368234 1 RANDER SURAT 16 MOHAMMAD SAMSUL HAQE 9402620463 1 KOSAMBA SURAT 17 MD RAHISH 8414070711 1 KOSAMBA SURAT 18 Mo.Kamal Akman pathan 8575812127 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 19 Syeed Liyakat Ali Tabarak 8567610162 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 20 Md.Anis Khan A.Kasim 7630051746 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 21 Md.IrfanKhan Feijuddin 8511296539 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 22 Altaf Tomba 9862945355 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 23 Md.Nawaj sarif Feijuddin 9856761078 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 24 Md.Rezwan Ahamed R 9856983176 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 25 Md.Nawaj khan Tomba 9862945355 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 26 Md.Anish Ibosana 9383350481 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 27 Md.Noman Asrap ali 9383213129 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 28 Tajkhan abdulsamad 8575509412 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 29 Md.Juber Jamir 9612338278 1 CITY WEST Vadodara Yumkhaibam Rahis Khan 30 9612621666 1 CITY WEST Vadodara Ithem 31 Md.Mirza Soukatali 9856407547 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 32 Syeed sikandar Ali T 6909958988 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 33 Th Wasim A.Manal 7306216873 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 34 Md.Amir Ayub 9612719347 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 35 Md.Firdos Feroj shkh 9383278174 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 36 Syeed sultan Alam T 8132028700 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 37 Mo.sufiyan Islauddin 6239023946 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 38 Mo.Musaraf Salaodin 8974788491 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 39 W. -

Missionaries, the Princely State and Medicine in Travancore, 1858-1949

14 ■Article■ Missionaries, the Princely State and Medicine in Travancore, 1858-1949 ● Koji Kawashima 1. Introduction Growing attention has recently been paid to the history of medi- cine and public health in India, and many scholars have already made substantial contributions. Some of their main concerns are: British policy regarding medicine and public health in colonial India, indigenous responses to this Western science and practices , the impact of epidemic diseases on Indian society, the relationship between Western and indigenous medicine in the colonial period, and, as David Arnold has recently researched, the process in which Western medicine became part of a cultural hegemony in India as well as the creation of discourses on India and colonialism by Western medicine.1) Perhaps one of the problems of these studies is that they are almost totally confined to British India, in which the British di- rectly ruled and played a principal role in introducing Western medicine. The princely states, which occupied two-fifths of India before 1947, have been almost completely ignored by the histori- ans of medicine and public health. What policies with regard to 川 島 耕 司 Koji Kawasima, Part-time lecturer, University of Mie, South Asian History. Other research works include: "Missionaries , the Princely State and British Paramountcy in Travancore and Cochin, 1858-1936", Ph. D. Thesis, University of London, 1994. Missionaries, the Princely State and Medicine in Travancore, 1858-1949 15 Western as well as indigenous medicine were adopted in the terri- tories ruled by the Indian princes? What difference did indirect rule make in the area of medicine? One of the aims of this essay is to answer these questions by investigating the medical policies of Travancore, one of the major princely states in India. -

THE LANGUAGES of MANIPUR: a CASE STUDY of the KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 34.1 — April 2011 THE LANGUAGES OF MANIPUR: A CASE STUDY OF THE KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar Abstract: Manipur is primarily the home of various speakers of Tibeto-Burman languages. Aside from the Tibeto-Burman speakers, there are substantial numbers of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian speakers in different parts of the state who have come here either as traders or as workers. Keeping in view the lack of proper information on the languages of Manipur, this paper presents a brief outline of the languages spoken in the state of Manipur in general and Kuki-Chin languages in particular. The social relationships which different linguistic groups enter into with one another are often political in nature and are seldom based on genetic relationship. Thus, Manipur presents an intriguing area of research in that a researcher can end up making wrong conclusions about the relationships among the various linguistic groups, unless one thoroughly understands which groups of languages are genetically related and distinct from other social or political groupings. To dispel such misconstrued notions which can at times mislead researchers in the study of the languages, this paper provides an insight into the factors linguists must take into consideration before working in Manipur. The data on Kuki-Chin languages are primarily based on my own information as a resident of Churachandpur district, which is further supported by field work conducted in Churachandpur district during the period of 2003-2005 while I was working for the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore, as a research investigator. -

Distinctive Cultural and Geographical Legacy of Bahawalpur by Samia Khalid and Aftab Hussain Gilani

Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies Vol. 2, No. 2 (2010) Distinctive Cultural and Geographical Legacy of Bahawalpur By Samia Khalid and Aftab Hussain Gilani Geographical introduction: The Bahawalpur State was situated in the province of Punjab in united India. It was established by Nawab Sadiq Muhammad Khan I in 1739, who was granted a title of Nawab by Nadir Shah. Technically the State, had come into existence in 1702 (Aziz, 244, 2006).1 According to the first English book on the State of Bahawalpur, published in mid 19th century: … this state was bounded on east by the British possession of Sirsa, and on the west by the river Indus; the river Garra forms its northern boundary, Bikaner and Jeyselmeer are on its southern frontier…its length from east to west was 216 koss or 324 English miles. Its breadth varies much: in some parts it is eighty, and in other from sixty to fifteen miles. (Ali, Shahamet, b, 1848) In the beginning of the 20th century, this State lay in the extreme south- west of the Punjab province, between 27.42’ and 30.25’ North and 69.31’ and 74.1’ East with an area of 15,918 square miles. Its length from north-east to south-west was about 300 miles and its mean breadth is 40 miles. Of the total area, 9,881 square miles consists of desert regions with sand-dunes rising to a maximum height of 500 feet. The State consists of 10 towns and 1,008 villages, divided into three Nizamats (administrative Units): Minchinabad, Bahawalpur and Khanpur. -

Neo-Vernacularization of South Asian Languages

LLanguageanguage EEndangermentndangerment andand PPreservationreservation inin SSouthouth AAsiasia ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 7 Language Endangerment and Preservation in South Asia ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 7 PUBLISHED AS A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION LANGUAGE ENDANGERMENT AND PRESERVATION IN SOUTH ASIA Special Publication No. 7 (January 2014) ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 USA http:/nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I PRESS 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822-1888 USA © All text and images are copyright to the authors, 2014 Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives License ISBN 978-0-9856211-4-8 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4607 Contents Contributors iii Foreword 1 Hugo C. Cardoso 1 Death by other means: Neo-vernacularization of South Asian 3 languages E. Annamalai 2 Majority language death 19 Liudmila V. Khokhlova 3 Ahom and Tangsa: Case studies of language maintenance and 46 loss in North East India Stephen Morey 4 Script as a potential demarcator and stabilizer of languages in 78 South Asia Carmen Brandt 5 The lifecycle of Sri Lanka Malay 100 Umberto Ansaldo & Lisa Lim LANGUAGE ENDANGERMENT AND PRESERVATION IN SOUTH ASIA iii CONTRIBUTORS E. ANNAMALAI ([email protected]) is director emeritus of the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore (India). He was chair of Terralingua, a non-profit organization to promote bi-cultural diversity and a panel member of the Endangered Languages Documentation Project, London.