Alaska's Highways and Byways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alberta-To-Alaska-Railway-Pre-Feasibility-Study

Alberta to Alaska Railway Pre-Feasibility Study 2015 Table of Content Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... i Infrastructure and Operating Requirements................................................................ ii Environmental Considerations and Permitting Requirements .................................... ii Capital and Operating Cost Estimates ......................................................................... iii Business Case .............................................................................................................. iii Mineral Transportation Potential ................................................................................ iii First Nations/Tribes and Other Contacts ..................................................................... iv Conclusions .................................................................................................................. iv 1 | Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 This Assignment............................................................................................................ 1 This Report ................................................................................................................... 2 2 | Infrastructure and Operating Requirements ........................................................ 3 Route Alignment .......................................................................................................... -

A Tale of Perseverance and Ingenuity Perseverance of a Tale by Ben Traylor

A Tale of Perseverance and Ingenuity Perseverance of A Tale by Ben Traylor Through excellent customer service and sound business management practices, provide safe, efficient, and economical transportation and real estate services that support and grow economic development opportunities for the State of Alaska. by Scott Adams Scott by TABLE OF CONTENTS Alaska Railroad Leadership 1 Leadership Year in Review 2 Business Highlights 8 Financial Highlights 10 Transmittal Letter 12 AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SECTION Contact Information and Office Locations Back by Judy Patrick Judy by MANAGEMENT TEAM Clark Hopp Jim Kubitz Chief Operating Officer VP Real Estate Barbara Amy Brian Lindamood Chief Financial Officer VP Engineering Andy Behrend Dale Wade Chief Counsel VP Marketing and Bill O’Leary Customer Service President & CEO Jennifer Haldane Chief Human Resources Officer BOARD OF DIRECTORS Craig Campbell Judy Petry Julie Anderson John Binkley Chair Vice Chair Commissioner Director Gov. Mike Dunleavy appointed Bill Sheffield as by Ken Edmier Ken by Chair Emeritus Jack Burton John MacKinnon John Shively Director Commissioner Director 1 YEAR IN REVIEW A Tale of Perseverance and Ingenuity Once upon a time, in a world not yet steeped in pandemic, the Alaska Railroad Corporation (ARRC) began the year 2020 with optimism, ready to share a story of emergence from fiscal uncertainty. Yet, when the last page turned on 2020, our tale didn’t end with happily-ever-after; nor did it conclude as a tragedy. Instead, 2020’s narrative featured everyday heroes, brandishing their perseverance and ingenuity to fight common foes — the villain Pandemic and its sidekick Recession. Just two months into a promising new year, the rogue novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) appeared on scene, soon spreading throughout the land. -

Moving to Haines: Relocation Guide

Moving to Haines: Relocation Guide Haines Visitor Center 122 Second Ave. PO Box 530 Information is based upon services and information Haines, AK 99827 available as of the summer of 2020 PH: (907)766-6418 Email: [email protected] Information gathered by the Haines Visitor Center Web: www.visithaines.com 32 1 Welcome To Moving your pet to Haines Both the USA and Canadian Customs require dogs to have a Haines, Alaska current, valid rabies vaccination certificate to cross the border: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/pet-travel/by-country/ Nestled between North America’s deepest fjord and the pettravel-canada. Chilkat Range. Whether you come for a summer adventure or Pet carriers and current health certificates are required for wanting to relocate. Haines offers an amazing array of nature, transporting pets via air and on the state ferry (AMHS). outings and sports activities, as well as cultural, entertainment Alaska Airlines policy: https://www.pettravel.com/ and dining opportunities. airline_pet_rules/laskaairlines.cfm. AMHS Animal Policy: http://www.dot.state.ak.us/amhs/ One of 3 communities in Southeast Alaska with road access to policies.shtml. the lower 48. Haines is 85 air miles north of the capital city of Veterinarian Services Juneau and about 600 air miles southeast of Anchorage and Regular medical care for your pet takes a bit more planning Fairbanks. It is connected by road to the interior of Alaska when you are in Haines. Securely attach an ID Collar to your and the continental United States by the Alaska Canada pet with name & your contact info. -

AGDC Plan Template DRAFT 7Aug2012

ALASKA STAND ALONE PIPELINE/ASAP PROJECT DRAFT Wetlands Compensatory Mitigation Plan ASAP-22-PLN-REG-DOC-00001 November 10, 2016 DRAFT Wetlands Compensatory Mitigation Plan REVISION HISTORY Approval Revision Date Comment Company Preparing AGDC Report 0 11/10/2016 Draft AGDC K Stevenson / M Thompson Document No: ASAP 22-PLN-REG-DOC-00001 Date: November 10, 2016 Page ii NOTICE – THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS CONFIDENTIAL AND PROPRIETARY INFORMATION AND SHALL NOT BE DUPLICATED, DISTRIBUTED, DISCLOSED, SHARED OR USED FOR ANY PURPOSE EXCEPT AS MAY BE AUTHORIZED BY AGDC IN WRITING. THIS DOCUMENT IS UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED. THIS COPY VALID ONLY AT THE TIME OF PRINTING DRAFT Wetlands Compensatory Mitigation Plan ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ADF&G Alaska Department of Fish and Game ADNR-PMC Alaska Department of Natural Resources – Plant Materials Center ADPOT&PF Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities AES ASRC Energy Services AGDC Alaska Gasline Development Corporation AKWAM Alaska Wetland Assessment Method AKLNG Alaska LNG ARR Alaska Railroad ASAP Alaska Stand Alone Pipeline ASA Aquatic Site Assessment ASRC Arctic Slope Regional Corporation CEQ Council on Environmental Quality CFR Code of Federal Regulations CMP Wetland Compensatory Mitigation Plan DA Department of the Army EED Environmental Evaluation Document ENSTAR EPA United States Environmental Protection Agency ERL Environmental, Regulatory, and Land FCI Functional Capacity Index FEIS Final Environmental Impact Statement ft Foot / feet GCF Gas Conditioning Facility HDD Horizontal directional drilling HGM hydrogeomorphic HUC Hydrologic Unit ILF in-lieu fee LEDPA Least Environmentally Damaging Practicable Alternative Mat-Su Matanuska-Susitna MSB Matanuska-Susitna Borough Document No: ASAP 22-PLN-REG-DOC-00001 Date: November 10, 2016 Page iii NOTICE – THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS CONFIDENTIAL AND PROPRIETARY INFORMATION AND SHALL NOT BE DUPLICATED, DISTRIBUTED, DISCLOSED, SHARED OR USED FOR ANY PURPOSE EXCEPT AS MAY BE AUTHORIZED BY AGDC IN WRITING. -

Field-Trip Guide to Volcanic and Volcaniclastic Deposits of the Lower Jurassic Talkeetna Formation, Sheep Mountain, South-Central Alaska

Field-Trip Guide to Volcanic and Volcaniclastic Deposits of the Lower Jurassic Talkeetna Formation, Sheep Mountain, South-Central Alaska U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2006-1124 Field-Trip Guide to Volcanic and Volcaniclastic Deposits of the Lower Jurassic Talkeetna Formation, Sheep Mountain, South-Central Alaska Amy E. Draut U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Science Center, Santa Cruz, CA 95060 Peter D. Clift School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen, AB24 3UE, U.K. Robert B. Blodgett U.S. Geological Survey–Contractor, Anchorage, AK 99508 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 2006-1124 2006 U.S. Department of the Interior P. Lynn Scarlett, Acting Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 2006 Revised and reprinted: 2006 Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government To download a copy of this report from the World Wide Web: http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2006/1124/ For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 1. Regional map of the field-trip area. FIGURE 2. Geologic cross section through Sheep Mountain. FIGURE 3. Stratigraphic sections on the south side of Sheep Mountain. -

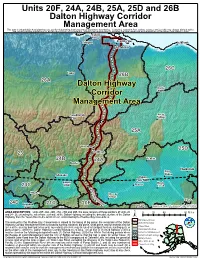

Dalton Highway Corridor Management Area ! This Map Is Intended for Hunt Planning Use, Not for Determining Legal Property Or Regulatory Boundaries

Units 20F, 24A, 24B, 25A, 25D and 26B Dalton Highway Corridor Management Area ! This map is intended for hunt planning use, not for determining legal property or regulatory boundaries. Content is compiled from various sources and is subject to change without notice. See current hunting regulations for written descriptions of boundaries. Hunters are responsible for knowing the land ownership and regulations of the areas they intend to hunt. Colville ! Village Prudhoe Bay Nuiqsut ! Kaktovik ! ! ! Deadhorse 26C Umiat ! 26B 26A Dalton Highway Arctic Corridor NWR Management Area Anaktuvuk Arctic Pass Village ! ! 25A Wiseman ! 25D 23 ! Coldfoot Venetie ! 24B 24A ! Bettles ! Chalkyitsik Fort ! Yukon Allakaket ! ! Yukon Arctic Circle Flats NWR Kanuti Birch 24C NWR ! Beaver Creek D ! A L T Hughes O ! N Stevens Village H ! IG H Circle W ! ! 24D Koyukuk 21C 20F AY NWR 20F 25C Sources: Esri, DeLorme, USGS,25B NPS AREA DESCRIPTION: Units 20F, 24A, 24B, 25A, 25D and 26B, the area consists of those portions of Units 20 0 20 40 ! 80 Miles and 24 - 26 extending five miles from each side of the Dalton Highway, including the driveable surface of the Dalton ! ± Highway, from the Yukon River to the Arctic Ocean, and including the Prudhoe Bay Closed Area. Management Area The area within the Prudhoe Bay Closed Area is closed to the taking of big game; the remainder of the Dalton Subunit Boundary Highway Corridor Management Area is closed to hunting; however, big game, small game, and fur animals may be Closed Area taken in the area by bow and arrow only; no -

Tangle Lakes Archaeological District

DNR BLM A Window to the Past Wide Open Spaces Riding Responsibly Stay on designated trails Tangle Lakes Archaeological Secrets of lives lived long ago are hidden Not only is this a place to imagine and No pioneering of new trails amidst the jagged up-thrusts of mountains and appreciate the past, it is also a wonderland District the sweeping grandeur of glaciers in south- for outdoor activites. The Tangle Lakes Respect other trail users central Alaska. Located along the Denali Archaeological District has many uses Highway between mileposts 17 and 37 is an including: Use improved trails when available area rich in historic and prehistoric remains Information Guide called the Tangle Lakes Archaeological • hiking • horseback riding Cross streams at designated District (TLAD). • camping • photography crossings only and Trails Map • berry picking • fi shing This area has more than 600 archaeological • snow machining • boating Pack out your garbage sites with artifacts from pit-houses to hand- • hunting • wildlife watching fashioned stone tools. Carbon dating tests • mining • off-highway vehicle Plan ahead and be prepared have helped identify four different cultural • biking riding traditions displayed in the timeline below. Know your limits To protect environmentally sensitive areas Do not collect or disturb artifacts Cultural Traditions of the Past and our historic heritage, the Bureau of Land Historical Management (BLM) and the State of Alaska Denali Northern Archaic Athapaskan Presen Additional information can be found at Complex Tradition Tradition Period Department of Natural Resources (DNR) www.treadlightly.org t have designated 8 trails open for off-highway 10,000* 7,000* 1,000* 200* vehicle (OHV) use within the Tangle Lakes Archaeological District. -

Haines Highway Byway Corridor Partnership Plan

HAINES HIGHWAY CORRIDOR PARTNERSHIP PLAN 1 Prepared For: The Haines Borough, as well as the village of Klukwan, and the many agencies, organizations, businesses, and citizens served by the Haines Highway. This document was prepared for local byway planning purposes and as part of the submission materials required for the National Scenic Byway designation under the National Scenic Byway Program of the Federal Highway Administration. Prepared By: Jensen Yorba Lott, Inc. Juneau, Alaska August 2007 With: Whiteman Consulting, Ltd Boulder, Colorado Cover: Haines, Alaska and the snow peaked Takhinska Mountains that rise over 6,000’ above the community 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION..............................................................5-9 2. BACKGROUND ON Byways....................................11-14 3. INSTRINSIC QUALITY REVIEW..............................15-27 4. ROAD & TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM...................29-45 5. ToURISM & Byway VISITATION...........................47-57 6. INTERPRETATION......................................................59-67 7. PURPOSE, VISION, GOALS & OBJECTIVES.......69-101 8. APPENDIX..................................................................103-105 3 4 INTRODUCTION 1 Chilkat River Valley “Valley of the Eagles” 5 The Haines Highway runs from the community byway. Obtaining national designation for the of Haines, Alaska to the Canadian-U.S. border American portion of the Haines highway should station at Dalton Cache, Alaska. At the half way be seen as the first step in the development of an point the highway passes the Indian Village of international byway. Despite the lack of a byway Klukwan. The total highway distance within Alaska program in Canada this should not prevent the is approximately 44 miles, however the Haines celebration and marketing of the entire Haines Highway continues another 106 miles through Highway as an international byway. -

Ordinance 11-19

DENALI BOROUGH, ALASKA ORDINANCE NO.__11-19_____ VERSION A INTRODUCED BY: _Mayor Dave Talerico___ AN ORDINANCE AMENDING THE DENALI BOROUGH CHARTER BY ADDING APPENDIX A AND AMENDING ARTICLE II, SECTION 2.02 OF THE DENALI BOROUGH CHARTER TITLED ASSEMBLY COMPOSITION. Section 1. Classification. This ordinance is of a general and permanent nature. Section 2. Purpose. The purpose of this ordinance is to amend the Denali Borough Charter by adding Appendix A containing the map of the five Denali Borough Assembly Districts (attached) and the listings of the 2010 U.S. Census Blocks making up each Assembly District (attached) and deleting the current language of Section 2.02 of Article II and replacing it with the language as follows: Section 2.02 Composition 1. The Assembly elected by the qualified voters of the Denali Borough shall consist of nine (9) Assembly members. The districts are composed of the following: A. District - 1 Seat – A Generally described as: Parks Highway (MP 215.3) from just south of the first Nenana River Bridge (located north of Cantwell) to the southern Denali Borough boundary (MP 202) and the portion of the Denali Highway contained within the Denali Borough including the community of Cantwell. (See Assembly District – 1 on the Denali Borough Assembly Districts Map in Appendix A) Specifically described as: The 2010 U.S. Census Blocks listed under Assembly District – 1 in Appendix A. B. District – 2 Seat – B Generally described as: Parks Highway south of Riley Creek (MP 237.2) to just south of the first Nenana River Bridge (MP 215.3) including the community of McKinley Village. -

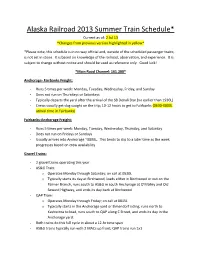

Alaska Railroad 2013 Summer Train Schedule* Current As Of: 2 Jul 13 *Changes from Previous Version Highlighted in Yellow*

Alaska Railroad 2013 Summer Train Schedule* Current as of: 2 Jul 13 *Changes from previous version highlighted in yellow* *Please note, this schedule is in no way official and, outside of the scheduled passenger trains, is not set in stone. It is based on knowledge of the railroad, observation, and experience. It is subject to change without notice and should be used as reference only. Good luck! *Main Road Channel: 161.280* Anchorage- Fairbanks Freight: - Runs 5 times per week: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday, and Sunday - Does not run on Thursdays or Saturdays - Typically departs the yard after the arrival of the SB Denali Star (no earlier than 1930L) - Crews usually get dog caught on the trip; 10-12 hours to get to Fairbanks (0630-0800L arrival time in Fairbanks) Fairbanks-Anchorage Freight: - Runs 5 times per week: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Saturday - Does not run on Fridays or Sundays - Usually arrives into Anchorage ~0800L. This tends to slip to a later time as the week progresses based on crew availability Gravel Trains: - 2 gravel trains operating this year - AS&G Train: o Operates Monday through Saturday; on call at 0530L o Typically starts its day at Birchwood, loads either in Birchwood or out on the Palmer Branch, runs south to AS&G in south Anchorage at O’Malley and Old Seward Highway, and ends its day back at Birchwood - QAP Train: o Operates Monday through Friday; on call at 0815L o Typically starts in the Anchorage yard or Elmendorf siding, runs north to Kashwitna to load, runs south to QAP along C Street, and ends its day in the Anchorage yard. -

Richardson Highway / Steese Expressway Corridor Study Draft Purpose and Need

Richardson Highway / Steese Expressway Corridor Study Draft Purpose and Need The Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (ADOT&PF), in cooperation with the Alaska Division Office of the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), is developing a Planning and Environmental Linkage (PEL) Study for the Fairbanks, Alaska area Richardson Highway / Steese Expressway corridors from Badger Road interchange (Richardson Highway milepost 360) to Chena Hot Springs Road interchange (Steese Highway milepost 5). Purpose The purpose of the study is to collaborate with State, local, and federal agencies, the general public, and interested stakeholders to develop a shared corridor concept that meets long ‐range transportation needs to improve safety, mobility, air quality, and freight operations. Additionally, the concept will promote improvements that reduce transportation deficiencies (e.g. delay and congestion), enhance the corridor’s sustainability (e.g. infrastructure longevity and maintenance costs), and minimize environmental and social impacts. Project Need Summary I – Safety Safety for motorized and non‐motorized traffic needs improvement by developing a corridor concept that: Upgrades the transportation infrastructure to current ADOT&PF design standards where practical Reduces conflict points Reduces the frequency and severity of crashes at “high crash locations” Improves pedestrian and bicycle crossings II – Mobility The mobility of people and goods in the corridor needs improvement by developing a concept that: Reduces delay -

SUMMER 2021 Starts May 28Th - Sept 11Th

ITT 2021 Summer Packages Seward Fishing Club PKG 1: One day is all it takes 6 Hr. Salmon and Rock Fish Tour The best way to see Alaska is by rail. Enjoy an exciting day aboard the Coastal Classic Rail to Seward. Depart Anchorage at 6 AM,10 AM , 1PM departures $189 per person 6:45am, enjoy breakfast in the dining car (for an additional cost) and arrive to Seward at 11:05am. Get on board Major Marine’s (June 14 — August 31) 6 hour National Park Cruise from 11:30am-5:30pm. Return in time to depart on the rail at 6pm and arrive in Anchorage at 10:15pm. Adult - $275.60 Value Season $289.85 Peak Season Child - $139.55 Value Season $147.05 Peak Season **Cruise can be substituted at different costs for 6 Hour Natl Park w/ Kenai Fjords Tours** PKG 2: Talkeetna Day Trip Take a day trip to Talkeetna. Depart Anchorage at 8am to ride the Alaska Railroad North and arrive this picturesque little town ZIPLINE at 11:05am. Enjoy panoramic views of Mt. Denali aboard Mahays’ Jet boat Safari. Embark upon the 2hr Wilderness Jet $134 Adult Boat Adventure at 12 pm, which will also visit an authentic trap- $107 Child pers cabin on your quarter mile wilderness walk. Depart Talkeetna at 4:55pm and arrive back to Anchorage at 8pm. Stoney Creek (Seward) SUMMER 2021 Starts May 28th - Sept 11th. Operating Wednesdays– Sundays Adult - $200 Value Season $230 Peak Season Child - $120 Value Season $135 Peak Season Open Denali Zip line Tours (Talkeetna) Monday-Friday PKG 3: Discover Prince William Sound May 26th— Sept 11th Board the Alaska Railroad in Anchorage at 9:45am.