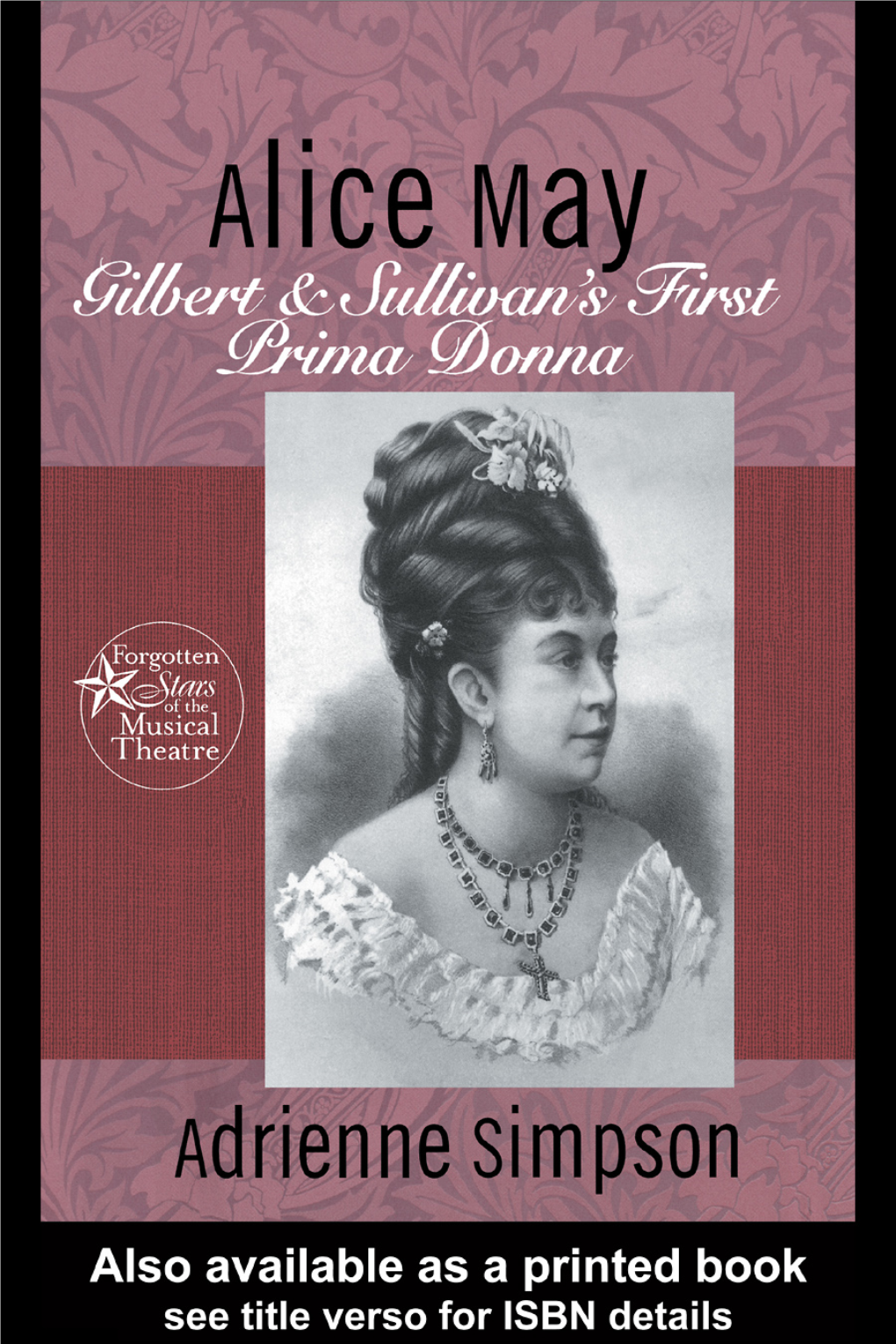

Alice May: Gilbert and Sullivan's First Prima Donna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com SirArthurSullivan ArthurLawrence,BenjaminWilliamFindon,WilfredBendall \ SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. From the Portrait Pruntfd w 1888 hv Sir John Millais. !\i;tn;;;i*(.vnce$. i-\ !i. W. i ind- i a. 1 V/:!f ;d B'-:.!.i;:. SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN : Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. By Arthur Lawrence. With Critique by B. W. Findon, and Bibliography by Wilfrid Bendall. London James Bowden 10 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.C. 1899 /^HARVARD^ UNIVERSITY LIBRARY NOV 5 1956 PREFACE It is of importance to Sir Arthur Sullivan and myself that I should explain how this book came to be written. Averse as Sir Arthur is to the " interview " in journalism, I could not resist the temptation to ask him to let me do something of the sort when I first had the pleasure of meeting ^ him — not in regard to journalistic matters — some years ago. That permission was most genially , granted, and the little chat which I had with J him then, in regard to the opera which he was writing, appeared in The World. Subsequent conversations which I was privileged to have with Sir Arthur, and the fact that there was nothing procurable in book form concerning our greatest and most popular composer — save an interesting little monograph which formed part of a small volume published some years ago on English viii PREFACE Musicians by Mr. -

Early 20Th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: a Cosmopolitan Genre

This is a repository copy of Early 20th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: A Cosmopolitan Genre. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/150913/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Scott, DB orcid.org/0000-0002-5367-6579 (2016) Early 20th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: A Cosmopolitan Genre. The Musical Quarterly, 99 (2). pp. 254-279. ISSN 0027-4631 https://doi.org/10.1093/musqtl/gdw009 © The Author 2016. Published by Oxford University Press. This is an author produced version of a paper published in The Musical Quarterly. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Early 20th-Century Operetta from the German Stage: A Cosmopolitan Genre Derek B. Scott In the first four decades of the twentieth century, new operettas from the German stage enjoyed great success with audiences not only in cities in Europe and North America but elsewhere around the world.1 The transfer of operetta and musical theatre across countries and continents may be viewed as cosmopolitanism in action. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

PARLOPHON Matrix Numbers — 2-9000 to 2-9999: British Discography Compiled by Christian Zwarg for GHT Wien Diese Diskographie Dient Ausschließlich Forschungszwecken

PARLOPHON Matrix Numbers — 2-9000 to 2-9999: British Discography compiled by Christian Zwarg for GHT Wien Diese Diskographie dient ausschließlich Forschungszwecken. Die beschriebenen Tonträger stehen nicht zum Verkauf und sind auch nicht im Archiv des Autors oder der GHT vorhanden. Anfragen nach Kopien der hier verzeichneten Tonaufnahmen können daher nicht bearbeitet werden. Sollten Sie Fehler oder Auslassungen in diesem Dokument bemerken, freuen wir uns über eine Mitteilung, um zukünftige Updates noch weiter verbessern und ergänzen zu können. Bitte senden Sie Ihre Ergänzungs- und Korrekturvorschläge an: [email protected] This discography is provided for research purposes only. The media described herein are neither for sale, nor are they part of the author's or the GHT's archive. Requests for copies of the listed recordings therefore cannot be fulfilled. Should you notice errors or omissions in this document, we appreciate your notifying us, to help us improve future updates. Please send your addenda and corrigenda to: [email protected] master 2-9000 master 2-9001 master 2-9002 master 2-9003 1911.08. D30 AN GBR: London, Beka Record Co. Head Office, 77 City Road, E.C. Where My Caravan Has Rested — Song (Hermann Löhr / Edward Teschemacher) Julian Jones (MD). — (orchestra). Giuseppe Lenghi-Cellini (tenor). master 2-9004 1911.08. D30 AN GBR: London, Beka Record Co. Head Office, 77 City Road, E.C. RIGOLETTO (Giuseppe Verdi / Francesco M. Piave) I/ 1: Questa o quella — Ballata {Duca} Questa o quella Julian Jones (MD). — (orchestra). Giuseppe Lenghi-Cellini (tenor). master 2-9005 1911.08. D30 AN GBR: London, Beka Record Co. -

Howard Glover's Life and Career

Howard Glover’s Life and Career Russell Burdekin, July 2019, updated September 2021 (This note was originally part of the preparation for a paper given at the Music in Nineteenth Century Britain Conference, Canterbury Christ Church University, July 5, 2019. See http://englishromanticopera.org/operas/Ruy_Blas/Howard_Glover_Ruy_Blas- harbinger_of_English_Romantic_Opera_demise.pdf ) This note was revised in September 2021 thanks to an email from David Gurney pointing me to Augustus William Gurney’s Memoir of Archer Thompson Gurney, which provided background on Glover’s early life as well as a summary of his character. A few other details have also been amended or added. William Howard Glover was born on 6 June 1819 in London, the second son of Julia Glover one of the best known actresses of the first half of the 19th century. Who his father was is less certain. By the end of 1817, Julia was living apart from her husband, Samuel.1 However, she was on very close terms with the American actor, playwright and author John Howard Payne, who was then living in London.2 The inclusion of Howard as Glover’s middle name and John rather than Samuel being written on the baptism record3 would strongly suggest that Payne was the father, although no definitive evidence has been found. Glover studied the violin with William Wagstaff, leader of the Lyceum Opera orchestra, and joined that band at the age of fifteen. By the age of sixteen had a dramatic scena performed at a Society of British Musicians concert.4 He continued his studies for some years in Italy, Germany and France (Illustrated Times 2 Sep. -

Class, Respectability and the D'oyly Carte Opera Company 1877-1909

THE UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER Faculty of Arts ‘Respectable Capers’ – Class, Respectability and the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company 1877-1909 Michael Stephen Goron Doctor of Philosophy June 2014 The Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research Degree of the University of Winchester The word count is: 98,856 (including abstract and declarations.) THE UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER ABSTRACT FOR THESIS ‘Respectable Capers’: Class, Respectability and the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company 1877-1909 Michael Stephen Goron This thesis will demonstrate ways in which late Victorian social and cultural attitudes influenced the development and work of the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, and the early professional production and performance of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas. The underlying enquiry concerns the extent to which the D’Oyly Carte Opera organisation and its work relate to an ideology, or collective mentalité, maintained and advocated by the Victorian middle- classes. The thesis will argue that a need to reflect bourgeois notions of respectability, status and gender influenced the practices of a theatrical organisation whose success depended on making large-scale musical theatre palatable to ‘respectable’ Victorians. It will examine ways in which managerial regulation of employees was imposed to contribute to both a brand image and a commercial product which matched the ethical values and tastes of the target audience. The establishment of a company performance style will be shown to have evolved from behavioural practices derived from the absorption and representation of shared cultural outlooks. The working lives and professional preoccupations of authors, managers and performers will be investigated to demonstrate how the attitudes and working lives of Savoy personnel exemplified concerns typical to many West End theatre practitioners of the period, such as the drive towards social acceptability and the recognition of theatre work as a valid professional pursuit, particularly for women. -

3 Oskar Nedbal – Nástin Života a Díla

Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Obecná teorie a dějiny umění a kultury – hudební věda Disertační práce Opereta Polská krev Oskara Nedbala v dobovém kontextu Operetta Polská Krev by Oskar Nedbal in Historical Context Školitelka: Prof. PhDr. Jarmila Gabrielová, CSc. 2016 MgA. Jiří Petrdlík Prohlášení: Prohlašuji, že jsem disertační práci napsal samostatně s využitím pouze uvedených a řádně citovaných pramenů a literatury a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu. V Praze, dne .................................... Jiří Petrdlík Poděkování: Na tomto místě bych rád vyslovil co nejupřímnější poděkování paní prof. PhDr. Jarmile Gabrielové, CSc. za její trpělivost, vstřícnost a citlivé vedení po celou dobu mého studia. Bez jejího velkorysého přístupu by můj výzkum a následně vznik této práce nebyl možný. Inspirativní konzultace, které mě vždy navedly správným směrem a díky nimž jsem si mohl výrazně rozšířit obzory na poli hudební vědy, náleží k největším přínosům mého dosavadního vzdělání. S velkými díky za vše, Jiří Petrdlík Klíčová slova: Oskar Nedbal, Polská krev, Polenblut, opereta, Vídeň, nedbaliana, konvolut, fascikl, autograf Keywords: Oskar Nedbal, Polish Blood, Polenblut, operetta, Vienna, Nedbal sources, convolute, folder, autograph Abstrakt: Oskar Nedbal patří mezi nejvýznamnější české hudební osobnosti konce 19. a počátku 20. století. Jeho přínos lze spatřovat nejen v oblasti interpretačního umění a hudebně organizačního úsilí, ale rovněž na poli skladatelském, především díky operetě Polská krev (Polenblut). Disertační práce se kromě nezbytného přehledu pramenů a literatury a nástinu života a díla Oskara Nedbala soustředí na otázku postavení operety Polská krev jak v rámci skladatelovy ostatní tvorby, tak i v širším kontextu vídeňské operety. -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

GILBERT and SULLIVAN: Part 1

GILBERT AND SULLIVAN: Part 1 GILBERT AND SULLIVAN Part 1: The Correspondence, Diaries, Literary Manuscripts and Prompt Copies of W. S. Gilbert (1836-1911) from the British Library, London Contents listing PUBLISHER'S NOTE CONTENTS OF REELS CHRONOLOGY 1836-1911 DETAILED LISTING GILBERT AND SULLIVAN: Part 1 Publisher's Note "The world will be a long while forgetting Gilbert and Sullivan. Every Spring their great works will be revived. … They made enormous contributions to the pleasure of the race. They left the world merrier than they found it. They were men whose lives were rich with honest striving and high achievement and useful service." H L Mencken Baltimore Evening Sun, 30 May 1911 If you want to understand Victorian culture and society, then the Gilbert and Sullivan operas are an obvious starting point. They simultaneously epitomised and lampooned the spirit of the age. Their productions were massively successful in their own day, filling theatres all over Britain. They were also a major Victorian cultural export. A new show in New York raised a frenzy at the box office and Harper's New Monthly Magazine (Feb 1886) stated that the "two men have the power of attracting thousands and thousands of people daily for months to be entertained”. H L Mencken's comments of 1911 have proved true. Gilbert & Sullivan societies thrive all over the world and new productions continue to spring up in the West End and on Broadway, in Buxton and Harrogate, in Cape Town and Sydney, in Tokyo and Hong Kong, in Ottawa and Philadelphia. Some of the topical references may now be lost, but the basis of the stories in universal myths and the attack of broad targets such as class, bureaucracy, the legal system, horror and the abuse of power are as relevant today as they ever were. -

H.M.S. Pinafore

H.M.S. PINAFORE or, The Lass that loved a Sailor An entirely Original Nautical Comic Opera Written by W.S. Gilbert Composed by Arthur Sullivan Rescued from Obscurity A Reprint series of Definitive Libretti of the „Savoy‟ and related operas. Edited by Ian C. Bond. Other Libretti in this Series AN ITALIAN STRAW HAT, or, “Haste to the Wedding” W.S. Gilbert, George Grossmith, et al. COX AND BOX - F.C. Burnand and Arthur Sullivan CREATURES OF IMPULSE - W.S. Gilbert and Alberto Randegger THE EMERALD ISLE - Basil Hood, Arthur Sullivan and Edward German FALLEN FAIRIES - W.S. Gilbert and Edward German THE GONDOLIERS - W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan “HASTE TO THE WEDDING” - W.S. Gilbert and George Grossmith JANE ANNIE - J.M. Barrie, Arthur Conan Doyle and Ernest Ford NO CARDS - W.S. Gilbert and Thomas German Reed THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE - W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan PRINCESS TOTO - W.S. Gilbert and Frederic Clay THE ROSE OF PERSIA - Basil Hood and Arthur Sullivan RUDDYGORE - W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan UTOPIA (LIMITED) - W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan THE VICAR OF BRAY - Sydney Grundy and Edward Solomon THE ZOO - B.C. Stephenson and Arthur Sullivan Vocal Scores AN ITALIAN STRAW HAT, or, “Haste to the Wedding” W.S. Gilbert, George Grossmith, et al. THE EMERALD ISLE - Basil Hood, Arthur Sullivan and Edward German THE ROSE OF PERSIA - Basil Hood and Arthur Sullivan (facsimile of a cued conductors score) In Preparation THE BEAUTY STONE - Arthur Wing Pinero, J. Comyns Carr and Arthur Sullivan THE BRIGANDS - H. -

Gagging for It: Irony, Innuendo and the Politics of Subversion in Women's

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Beale, Samantha ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3533-644X (2018) Gagging for it: irony, innuendo and the politics of subversion in women’s comic performance on the post-1880 London music-hall stage and its resonance in contemporary practice. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/23853/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

A'beckett, Gilbert Abbott, 175, 176, 182 Above and Below

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51901-4 — The Making of the West End Stage Jacky Bratton Index More Information Index A’Beckett, Gilbert Abbott, 175, 176, 182 Black-ey’d Susan (Jerrold), 87, 200 Above and Below (Stirling), 178 blackface minstrelsy, 58, 201. See also Christy’s Acis and Galatea (Handel), 135 Minstrels, Ethiopian Serenaders Adams, William Davenport, 200 Blanchard, E. L., 66, 70, 99, 103, 162 Adelaide Gallery, 39, 66 Blessington, Lady, 107 Adelphi, 9, 35, 37, 38, 129, 141, 148, 154, 163, 172, Bohemian Girl, The, 56 173, 180, 182, 188, 197, 200 Boleno, Harry, 55 under Celeste’s management, 196 Booth, Michael, 175, 176 Adolphus, Francis, 64 Boots at the Swan, The (Selby), 176 Alhambra Theatre, 30, 62, 203. See also Royal Boucicault, Dion, 68, 87, 195 Panopticon of Science and Art Braham, John, 112 Altick, Richard, 28 Bridal, The, 171 Argyll Rooms, 43 Brough, Robert, 102, 107 Armstrong, Isobel, 41 Marston Lynch, 97–8, 100–1, 106 Arnold, Matthew, 46, 50, 61, 85, 146 Brough, Robert and William, 135 Arnold, Samuel, 164 Brough, William, 107 Arundel Club, 36, 66, 104 Browning, Robert, 87 Auerbach, Nina, 169 Buckstone, John Baldwin, 12, 154, 162, 189, 190, 194 Bailey, Peter, 47 Bufton, Eleanor, 150 Balfe, Michael, 171 Bunn, Alfred, 10–11, 67, 122, 137, 140, 141 Bancroft, Mr and Mrs, 110, 196, 205. Burford’s Panorama, 29, 36 See also Wilton, Marie burlesque at the Strand Theatre, 204 Barnaby Rudge (Dickens et al.), 181 Byron, H. J., 111, 151, 200, 201, 202, 203 Barnett, C. L., 99 Barrie`re, Theodore, 95 Camp at the Olympic, The