Conference-Program.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book of Abstracts Global Perspectives on Media and Populism

Book of Abstracts Global Perspectives on Media and Populism Key Note Speakers Natalia Roudakova: Populism and Post-Truth: A Relationship Natalia Roudakova is a cultural anthropologist (Ph.D., Stanford University, 2007) working in the field of political communication and comparative media studies, with a broad interest in moral philosophy and political and cultural theory. She has worked as an Assistant Professor at the Department of Communication, University of California in San Diego, and most recently as a visiting scholar in the Media and Communication Department at Erasmus University in Rotterdam. In 2013- 2014, Roudakova was a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences in Palo Alto, California, where she completed her book manuscript titled Losing Pravda: Ethics and the Press in Post-Truth Russia which is now out with Cambridge University Press. Michael Schudson: Democracy, Desperation, and Distraction: Notes on Populism Today Michael Schudson grew up in Milwaukee, Wisc. He received a B.A. from Swarthmore College and M.A. and Ph.D. in sociology from Harvard. He taught at the University of Chicago from 1976 to 1980 and at the University of California, San Diego from 1980 to 2009. From 2005 on, he split his teaching between UCSD and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, becoming a full-time member of the Columbia faculty in 2009. He is the author of seven books and co-editor of three others concerning the history and sociology of the American news media, advertising, popular culture, Watergate and cultural memory. He is the recipient of a number of honors; he has been a Guggenheim fellow, a resident fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Palo Alto, and a MacArthur Foundation "genius" fellow. -

MAKING the UNIVERSITY MATTER DECEMBER 4-5, 2009 Presented by the Scholars Program in Culture and Communication Speakers

A Symposium Annenberg School for Communication University of Pennsylvania MAKING THE UNIVERSITY MATTER DECEMBER 4-5, 2009 Presented by The Scholars Program in Culture and Communication Speakers Ien Ang Risto Kunelius Visiting Scholar SummerCulture Sponsor Spring 2006 Finland 2008 S. Elizabeth Bird Don Mitchell MAKING THE Visiting Scholar Visiting Scholar Fall 2007 Spring 2008 UNIVERSITY MATTER Dominic Boyer Mark Anthony Neal Guest Lecturer Visiting Scholar Fall 2007 Fall 2008 Making the University Matter Michael Bromley Kaarle Nordenstreng investigates how academics situate SummerCulture Sponsor SummerCulture Sponsor themselves simultaneously in the Australia 2009 Finland 2008 university and the world, and how Nick Couldry Radhika Parameswaran doing so affects the viability of the Visiting Scholar Visiting Scholar university setting. The university Fall 2008 Spring 2009 stands at the intersection of two sets of interests, needing to be at one Michael X. Delli Carpini Jeff Pooley with the world while aspiring to stand ASC Faculty Panelist Visiting Scholar apart from it. In an era that promises John Nguyet Erni Spring 2009 intensified political instability, growing Visiting Scholar Richard Cullen Rath administrative pressures, dwindling Spring 2008 Visiting Scholar economic returns and questions about economic viability, lower Isabel Capeloa Gil Fall 2009 enrollments and shrinking programs, can the university continue SummerCulture Sponsor Paddy Scannell to matter into the future? And if so, in which way? What will help Portugal 2007 Guest Lecturer it survive as an honest broker? What are the mechanisms for Spring 2009 ensuring its independent voice? This two-day symposium considers Larry Gross a multiplicity of answers from across the curriculum on making the Guest Speaker Michael Schudson university matter, including critical scholarship, interdisciplinarity, Fall 2008 Guest Speaker curricular blends of the humanities and social sciences, practical Larry Grossberg Fall 2006 training and policy work. -

Reflecting on Forty Years of Sociology, Media Studies, and Journalism: an Interview with Todd Gitlin and Michael Schudson

Symposium “Value and Values in the Organizational Sociologica. V.14 N.2 (2020) Production of News” ISSN 1971-8853 https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/11515 https://sociologica.unibo.it/ Reflecting on Forty Years of Sociology, Media Studies, and Journalism: An Interview with Todd Gitlin and Michael Schudson Jiang Chang* Todd Gitlin† Michael Schudson‡ Submitted: September 4, 2020 – Accepted: September 5, 2020 – Published: September 18, 2020 Abstract Reflecting on more than four decades in dual scholarly careers that cut across thebound- aries between communication, the sociology of culture, and journalism studies, Professor ToddGitlin and Professor Michael Schudson discuss the growth, evolution, and strengths and weaknesses of the media studies field with Professor Jiang Chang. The three reflect on the origins of the research, the gap between the field of journalism studies and the fieldof sociology, the role played by journalism in the growing conflict between China and the United States, the relationship between media and political protest, and whether there ought be any cause for optimism regarding the state of democracy in the twenty-first cen- tury. Keywords: American Sociological Association; China; culture; Fox News; journalism studies; sociology. * Shenzhen University (China); [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8992-5410 † The Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and Chair of the Ph.D Program in Communica- tions (United States) ‡ The Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism (United States) Copyright © 2020 Jiang Chang, Todd Gitlin, Michael Schudson Art. #11515 The text in this work is licensed under the Creative Commons BY License. p. 249 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Reflecting on Forty Years of Sociology, Media Studies, and Journalism Sociologica. -

Knowledge, Expertise, and Professional Practice in the Sociology of Michael Schudson

This is a repository copy of Knowledge, Expertise, And Professional Practice in the Sociology of Michael Schudson. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/127474/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Anderson, CW (2017) Knowledge, Expertise, And Professional Practice in the Sociology of Michael Schudson. Journalism Studies, 18 (10). pp. 1307-1317. ISSN 1461-670X https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1335609 © 2017 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Journalism Studies on 16 June 2017, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1335609. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Knowledge, Expertise, and Professional Practice in the Sociology of Michael Schudson Pre-Publication Draft ABSTRACT: Although we often do not think of him this way, Michael Schudson can be seen as a moderate, critical-yet reasonable sociologist of knowledge. -

Objectivity and Professional Journalism in Transition in the Modern Media Ecology

REWRITING THE RULEBOOK, REVAMPING AN INDUSTRY: OBJECTIVITY AND PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISM IN TRANSITION IN THE MODERN MEDIA ECOLOGY by CHRISTINA LEFEVRE-GONZALEZ B.S., University of Texas at Austin, 1997 M.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2006 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Journalism and Mass Communication 2013 This dissertation entitled: Revising the Rulebook, Revamping an Industry: Objectivity and Professional Journalism in Transition in the Modern Media Ecology written by Christina Lefevre-Gonzalez has been approved for the Department of Journalism and Mass Communication _____________________________________________________ Professor Emeritus Robert Trager, Chair _____________________________________________________ Professor Stewart Hoover ______________________________________________________ Professor Michael McDevitt _____________________________________________________ Associate Professor Peter Simonson _____________________________________________________ Associate Professor Elizabeth Skewes Date ______________________ The final copy of this dissertation has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB protocols #12-0324 and #12-0715 Abstract Lefevre-Gonzalez, Christina (Ph.D., Communication) Revising the Rulebook, Revamping an Industry: Objectivity and -

Diffusion of the News Paradigm 1850-2000 Kevin G

Svennik Høyer and Horst Pöttker (eds.) Diffusion of the News Paradigm 1850-2000 Diffusion Kevin G. Barnhurst - Bernd Blöbaum - Jan Ekecrantz - Katharina Hadamik Hanno Hardt - Halliki Harro-Loit - Svennik Høyer - Søren Kolstrup - Epp Lauk John Nonseid - Jukka Pietiläinen - Horst Pöttker - Michael Schudson - Harlan Towards the turn of the 19th century, newspapers in the US were S. Stensaas - Rudolf Stöber - Kevin G. Barnhurst - Bernd Blöbaum - Jan expanding more rapidly than elsewhere. Was it this burgeoning market, Ekecrantz - Katharina Hadamik - Hanno Hardt - Halliki Harro-Loit - Svennik which inspired journalism to reinvent itself into a ‘new’ and different Høyer - Søren Kolstrup - Epp Lauk - John Nonseid - Jukka Pietiläinen - Horst Pöttker - Michael Schudson - Harlan S. Stensaas - Rudolf Stöber - Kevin G. kind of texts: clearer, fact oriented and without any obvious ideological Barnhurst - Bernd Blöbaum - Jan Ekecrantz - Katharina Hadamik - Hanno bias? Or were also broader cultural currents at work? Hardt - Halliki Harro-Loit - Svennik Høyer - Søren Kolstrup - Epp Lauk - John Nonseid - Jukka Pietiläinen - Horst Pöttker - Michael Schudson - Harland S. This anthology is one of a few, which compares the developments of Stensaas - Rudolf Stöber - KevinDiffusion G. Barnhurst - Bernd of Blöbaum the - Jan Ekecrantz - Katharina Hadamik - Hanno Hardt - Halliki Harro-Loit - Svennik Høyer - news journalism cross-nationally. The creation of a ‘news paradigm’ in Søren Kolstrup - Epp Lauk - John Nonseid - Jukka Pietiläinen - Horst Pöttker US is traced from its beginnings up to the present; its varying impacts Michael Schudson - HarlandNews S. Stensaas - RudolfParadigm Stöber - Kevin G. Barnhurst on European journalism is discussed and documented for England - Bernd Blöbaum - Jan Ekecrantz - Katharina Hadamik - Hanno Hardt - Halliki during the 1880s and 1890s, in Scandinavia between the 1870s and Harro-Loit - Svennik Høyer - Søren Kolstrup - Epp Lauk - John Nonseid - Jukka Pietiläinen - Horst Pöttker - Michael1850-2000 Schudson - Harland S. -

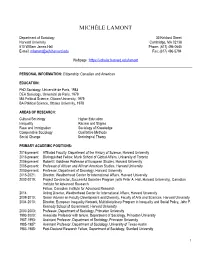

Michèle Lamont

MICHÈLE LAMONT Department of Sociology 33 Kirkland Street Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 510 William James Hall Phone: (617) 496-0645 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (617) 496-5794 Webpage : https://scholar.harvard.edu/lamont PERSONAL INFORMATION: Citizenship: Canadian and American EDUCATION: PhD Sociology, Université de Paris, 1983 DEA Sociology, Université de Paris, 1979 MA Political Science, Ottawa University, 1979 BA Political Science, Ottawa University, 1978 AREAS OF RESEARCH: Cultural Sociology Higher Education Inequality Racism and Stigma Race and Immigration Sociology of Knowledge Comparative Sociology Qualitative Methods Social Change Sociological Theory PRIMARY ACADEMIC POSITIONS: 2016-present: Affiliated Faculty, Department of the History of Science, Harvard University 2016-present: Distinguished Fellow, Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto 2006-present: Robert I. Goldman Professor of European Studies, Harvard University 2005-present: Professor of African and African American Studies, Harvard University 2003-present: Professor, Department of Sociology, Harvard University 2015-2021: Director, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University 2002-2019: Project Co-director, Successful Societies Program (with Peter A. Hall, Harvard University), Canadian Institute for Advanced Research Fellow, Canadian Institute for Advanced Research 2014: Acting Director, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University 2009-2010: Senior Advisor on Faculty Development and Diversity, Faculty -

Definitions of Journalism Barbie Zelizer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 2005 Definitions of Journalism Barbie Zelizer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation (OVERRIDE) Zelizer, B (2005). “Definitions of Journalism” in G. Overholser and K. H. Jamieson, eds., Institutions of American Democracy: The Press (pp. 66-80). New York: Oxford University Press. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/671 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Definitions of Journalism Disciplines Communication | Journalism Studies | Social and Behavioral Sciences This book chapter is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/671 4 DEFINITION S OF JOURNALISM Barbie Zelizer s JOURNALISM HAS COME TO BE THOUGHT OF AS A PRO- fession, an industry, a phenomenon, and a culture, definitions have A, emerged that reflect various concerns and goals.' Journalists,journalism educators, and journalism scholars all take different pathways in thinking pro- ductively about the subject, and the effort to define journalism consequently goes in various directions. Naming, labeling, evaluating, and critiquing journal- ism and journalistic practice reflect the populations from which individuals come, the type of news work, medium, and technology being referenced, and the relevant historical time period and geographical setting. No wonder, then, that the distinguished broadcast journalist Daniel Schorr noted that reporting was not only a livelihood for him but"a frame of mind.'" By extension,journalism as a frame of mind varies from individual to individual. Thinking aboutJournalism The various terms of news, the press, the news media, and information and communi- cation themselves suggestprofound differencesin what individuals consider jour- nalism to mean and what expectations they have of journalists.