Final Report For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Master Plan for Downtown

Rediscovering the Heart of Blacksburg A Master Plan for Downtown Final Report Completed By: The Blacksburg Collaborative MCA Urban Planning LDR International, Inc. Communitas August 31, 2001 Rediscovering the Heart of Blacksburg AMaster Plan for Downtown Final Report Completed By: The Blacksburg Collaborative MCA Urban Planning 5 Century Drive, Suite 210 Greenville, South Carolina 29606 864.232.8204 LDR International an HNTB Company 1 9175 Guilford Road Columbia, Maryland 21046 410.792.4360 Communitas 157 East Main Street, Suite 302 Rock Hill, South Carolina 29730 803.366.6374 August 31, 2001 2 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction............................................... 2 1.1 Purpose ..............................................................2 1.2 Process ...............................................................2 1.3 Report Format.....................................................3 1.4 Acknowledgments...............................................4 2.0 Rediscovering the Heart of Blacksburg -- The Master Plan......................................................... 6 2.1 Reconnecting Downtown With Its Citizens ...........6 2.2 A Retail Development Strategy ..........................22 2.3 An Arts and Entertainment Strategy...................33 2.4 A Tourism Strategy ...........................................37 2.5 A Residential Strategy .......................................43 2.6 An Economic Development Strategy ..................50 3.0 Implementation Strategy and Action Plan....56 3.1 Downtown Projects and Initiatives -

Innovation | Education | Business Creation Cover: the Hotel Roanoke at Dusk

THE VIRGINIA TECH FOUNDATION AND VIRGINIA TECH PHILANTHROPY Annual reports for fiscal year 2013-2014 Innovation | Education | Business Creation Cover: The Hotel Roanoke at dusk. Above: Students enjoy a fall day on campus. Virginia Tech Foundation Annual Report 2 Foundation Annual Report 2013-2014 04 Virginia Tech Foundation officers and administration 05 Virginia Tech Foundation Board of Directors 06 Virginia Tech Foundation properties 08 Ben J. Davenport Jr., Chairman of the Board 09 John E. Dooley, Chief Executive Officer and Secretary-Treasurer 10 A catalyst for growth and revitalization 20 Accomplishments and initiatives 23 Financial highlights 28 Foundation endowment highlights Philanthropy Annual Report 2013-2014 29 Mobilizing private support to help Virginia Tech and those it serves 30 University Development administration and directors 31 Elizabeth A. “Betsy” Flanagan, Vice President for Development and University Relations 32 Major gift highlights 37 Uses and sources of contributions 38 Designation of contributions 40 Virginia Tech giving societies 41 Ut Prosim Society membership list 51 Caldwell Society membership list 59 Legacy Society membership list Virginia Tech Foundation Annual Report 3 Officers Chairman of the Board Executive Vice President Ben J. Davenport Jr. Elizabeth A. Flanagan Chairman, Davenport Energy Inc. Vice President for Development and First Piedmont Corporation and University Relations, Virginia Tech Chief Executive Officer Executive Vice President and Secretary-Treasurer John E. Dooley M. Dwight Shelton Jr. CEO and Secretary-Treasurer, Vice President for Finance Virginia Tech Foundation Inc. and CFO, Virginia Tech Administration John E. Dooley Terri T. Mitchell CEO and Associate Vice President for Secretary-Treasurer Administration and Controller 540-231-2265 540-231-0420 [email protected] [email protected] Kevin G. -

Virginia Tech Football Strength & Conditioning Records

• Virginia Tech student-athletes receive outstanding academic support with state-of-the-art study areas and well over 95 tutors. • Tech’s athletic graduation rate is higher than the average overall graduation rate for all Division I universities and has risen significantly in the past few years. • More than 84 percent of all Tech student-athletes who enrolled during the 10-year period from 1987-88 through 1996-97 and completed their eligibility have graduated. • For the fifth year in a row, a new record of 371 student- athletes, HighTechs and cheerleaders were recognized at the Athletic Director’s Honors Breakfast for posting 3.0 GPAs or higher in the 2002 calendar year. • Tech had 212 student-athletes, approximately one-third of the student-athlete population, named to the dean’s list, and 28 Cedric Humes achieved a perfect 4.0 GPA during the fall or spring semesters of the 2002-03 academic year. • A total of 21 Tech athletic teams achieved a 3.0 or better team GPA — eleven teams during the fall semester and 10 during the spring semester. • Tech student-athletes participate in the HiTOPS program (Hokies Turning Opportunities into Personal Success). HiTOPS provides a well-rounded program for student-athletes to develop the individual skills necessary to lead successful and • Virginia Tech’s strength and conditioning program is regarded productive lives. as one of the best in the nation. • A full-time sports psychologist has been added to Tech’s • The Hokies have more than 22,000 square-feet of strength Athletic Performance Staff to help meet the personal and and conditioning training space. -

Agenda Item: Iii

MEMORANDUM To: NRVRC Board Members From: Jessica Barrett, Finance Technician Date: October 16, 2019 Re: September 2019 Financial Statements The September 2019 Agencywide Revenue and Expenditure Report and Balance Sheet are enclosed for your review. Financial reports are reviewed by the Executive Committee prior to inclusion in the meeting packet. The Agencywide Revenue and Expense report compares actual year to date receipts and expenses to the FY19-20 budget adopted by the Commission at the June 27, 2019 meeting. The financial operations of the agency are somewhat fluid and projects, added and modified throughout the year, along with the high volume of Workforce program activities, impact the adopted budget. To provide clarity, Commission and Workforce Development Board activities are separated on the agencywide report. As of month-end September 2019 (25% of the fiscal year), Commission year to date revenues are 28.16% and expenses are 27.59% of adopted budget. The two largest budget expense lines, Salary and Fringe, are in line with budget at 26.42% and 28.11%, respectively. Looking at the balance sheet, Accounts Receivable is $581,739. Of this total, Workforce receivables are $265,206 (46%) and current. Fiscal year-end procedures require all outstanding projects at year-end be closed into accounts receivable, resulting in an above average balance at the beginning of the fiscal year, but should return to average levels as the year progresses. The Executive Committee reviews all aged receivables over 60 days and no receivables are deemed uncollectible. Net Projects ($114,156) represents project expenses, primarily benchmark projects, that cannot be invoiced yet and posted to receivables. -

2015—2016 Adjunct Faculty Manual

2015—2016 Adjunct Faculty Manual 2 Table of Contents Introduction Program and Discipline Offerings .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Roster of Instructional Administrators.................................................................................................................................... 7 Roster of Administrative Professionals .................................................................................................................................. 7 Organizational Structure ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Wytheville Community College Mission Statement .............................................................................................................. 7 Wytheville Community College Statement of Values ............................................................................................................ 7 Wytheville Community College Vision Statement ................................................................................................................. 9 Educational Programs ............................................................................................................................................................. 9 Adjunct Faculty Adjunct (Part-Time) Faculty’s Job Responsibilities .............................................................................................................. -

Annual Report 2019-2020 GROWING DIVERSITY at VIRGINIA TECH VIRGINIA DIVERSITYGROWING at 28 Years and Counting

Center for Enhancement of Engineering Diversity Annual Report 2019-2020 GROWING DIVERSITY AT VIRGINIA TECH VIRGINIA DIVERSITYGROWING AT 28 Years and Counting... www.eng.vt.edu/CEED Since 1992, the Center for the Enhancement of Engineering Diversity (CEED) has provided encouragement and support to engineering students, focusing on the under-represented population. Our office recognizes that Virginia Tech students are among the best and brightest, and assists them in achieving excellence CEED’s Profile The Center for the Enhancement of Engineering Diversity (CEED) opened its doors in the fall of 1992. Since that time, the office has grown and expanded its efforts to provide encouragement and support to engineering students, focusing on the under-represented population. Virginia Tech students are among the best and brightest - our office recognizes this, and through various activities, we assist them in achieving the excellence of which they are capable.. Our Mission The Center for the Enhancement of Engineering Diversity (CEED) at Virginia Tech is dedicated to enriching the engineering profession through increased diversity. Our programs are targeted to current engineering students at Virginia Tech, prospective students, and the Commonwealth of Virginia’s pre-college community. Message from the Director These are interesting times. FY2019 started well, then end? Not so much. But we are still here and still supporting students as best we can. But we are weathering a lot of changes this past year. After 10 years, Susan Arnold Christian has left CEED and returned to her home in Kansas. What Su- san has built over time is an amazing living learning community – selected Best of VT. -

Corrective Action Permit Radford Army Ammunition Plant in Radford

COMMONWEALTH of VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY Street address: 629 East Main Street, Richmond, Virginia 23219 Molly Joseph Ward Mailing address: P.O. Box 1105, Richmond, Virginia 23218 David K. Paylor Secretary of Natural Resources www.deq.virginia.gov Director (804) 698-4000 1-800-592-5482 April 1, 2016 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL Mr. Jay Stewart Environmental Manager Radford Army Ammunition Plant 4050 Pepper’s Ferry Road Radford, Virginia 24141 Re: Approval of Reissuance of Hazardous Waste Management Corrective Action Permit Radford Army Ammunition Plant, Radford, VA EPA ID No.VA1210020730 Dear Mr. Stewart, Enclosed is the Final Hazardous Waste Management Corrective Action Permit for the Radford Army Ammunition Plant facility, Radford, Virginia. The Final Permit issuance has been approved and is scheduled to become effective on May 1, 2016. This final permit decision is in accordance with the Virginia Hazardous Waste Management Regulations (VHWMR), 9 VAC 20-60, 9 VAC-20-60-124, which incorporates 40 CFR Part 124 by reference, and in accordance with 40 CFR § 124.13, Obligation to Raise Issues and Provide Information During the Public Comment Period, which specifies: All persons, including applicants, who believe any condition of a draft permit is inappropriate or that the Director’s tentative decision to deny an application, terminate a permit, or prepare a draft permit is inappropriate, shall raise all reasonably ascertainable issues and submit all reasonably available arguments and factual grounds supporting their position, including all supporting material, by the close of public comment period (including any public hearing) under §124.10). Any supporting materials which are submitted shall be incorporated in full and may not be incorporated by reference, unless they are already part of the administrative record in the same proceeding, or consist of Commonwealth or federal statutes and regulations, documents of general applicability, or other generally available reference materials. -

New River Valley Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy

New River Valley Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy 2019 New River Valley Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy Table of Contents NEW RIVER VALLEY OVERVIEW ....................................................................................................................... 2 NEW RIVER VALLEY SWOT ANALYSIS ......................................................................................................... 10 PRIORITIES, GOALS, AND OBJECTIVES ....................................................................................................... 17 ANNUAL PROJECT PACKAGE REPORT ......................................................................................................... 23 APPENDICES ........................................................................................................................................................ 28 New River Valley CEDS 2019 Page 1 NEW RIVER VALLEY OVERVIEW 1. SUMMARY The New River Valley region consists of the counties of Floyd, Giles, Montgomery, Pulaski, and the City of Radford, and is home to ten incorporated towns. Much of the area is rural, consisting of mountain forests and farmland, with small communities of 1,000-10,000 residents that share many characteristics of neighboring Appalachian communities in southwest Virginia and West Virginia. The region has been growing steadily in recent years, especially in the “college towns” of Blacksburg (Virginia Tech) and Radford (Radford University) and in nearby Christiansburg. The activities of the two universities are -

Agenda Item: Iii

MEMORANDUM To: NRVRC Board Members From: Kevin R. Byrd, Executive Director Date: March 25, 2021 Re: Participation in NRVRC meetings through Electronic Communication Means Policy When the Governor has declared a state of emergency in accordance with section 44-146.17 of the Code of Virginia, it may become necessary for the NRV Regional Commission to meet by electronic means as outlined in Section 2.2-3708.2 of the Code of Virginia as amended. In such cases, the following procedure shall be followed: 1. The NRV Regional Commission will give notice to the public or common interest community association members using the best available method given the nature of the emergency, which notice shall be given contemporaneously with the notice provided to members of the NRV Regional Commission. 2. The NRV Regional Commission will make arrangements for public access or common interest community association members access to such meeting through electronic means including, to the extent practicable, videoconferencing technology. If the means of communication allows, provide the public or common interest community association members with an opportunity to comment 3. The NRV Regional Commission will otherwise comply with the provisions of § 2.2-3708.2 of the Code of Virginia. The nature of the emergency, the fact that the meeting was held by electronic communication means, and the type of electronic communication means by which the meeting was held shall be stated in the minutes of the NRV Regional Commission meeting. Strengthening the Region through Collaboration Counties Towns Higher Education Floyd │ Giles Blacksburg │ Christiansburg Virginia Tech Montgomery │ Pulaski Floyd │ Narrows │ Pearisburg Radford University City Pembroke │ Pulaski New River Community College Radford Rich Creek MEMORANDUM To: NRVRC Board Members From: Jessica Barrett, Finance Director Date: March 17, 2021 Re: February 2021 Financial Statements The February 2021 Agencywide Revenue and Expenditure Report and Balance Sheet are enclosed for your review. -

" Geology and the Civil War in Southwestern Virginia

," x--%"* J' : COMMONWEALTH OF P .: ,a & DePnRTMENT OF MINES, MWERALS AND */'? ?.l* .+--t4J Richmand, Virginia \ ,*"'j3 I"r.L" @.<G-*\,&- 2 ,s" VOL. 43 NOVEMBER 1997 NO. 4 GEOLOGY AND THE CIVIL WAR IN SOUTHWESTERN VIRGINIA: UNION RAIDERS IN THE NEW RIVER VALLEY, MAY 1864 Robert C. Whisonant Department of Geology Radford University Radford, VA 24142 INTRODUCTION connections between the geology, geography, and hum= history of this region. This article, part of an ongoing study examining the On Monday, May 9, 1864 - a beautiful sun-splashed &y in relationships between geology and the Civil War in southwestem the mountains of southwestern Virginia - the fargest Civil War Virginia (Whisonant 1996a; 1996b), probes these connections. battle ever fought in that sector of the Old omi in ion erupted at the base of Cloyds Mountain in Pulaski County (Figure 1). Both Yankee and Rebel veterans of that engagement, many of whom SALT, LEAD, AND RAIIS: had fought in larger and more important battfes elsewhere, THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SOUTHWESTERN claimed "that, for fierceness and intensity, Cloyds Mountain VIRGINIA TO THE CONFEDERATE WAR EFFORT exceeded them all" (Humphreys, 1924, cited in McManus, 1989). Of the roughly 9,000 soldiers engaged, 1,226 became When Civil War broke out in 1861, Virginia was by far the casualties. Union killed, wounded, and missing were leading mineral-producing state in the entire Confederacy approximately 10 percent of their forces and Confederate losses (Dietrich, 1970). Among the principal mined materials needed approached an appalling 23 percent. to fight a war in the 1860s were salt, iron, lead, niter (saltpeter), Next day, May 10, another lovely spring day, Northern and and coal (Whisonant, 1996a). -

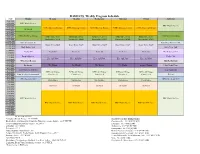

RADIO IQ Weekly Program Schedule

RADIO IQ Weekly Program Schedule TIME Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 5:00 AM 6:00 AM BBC World Service 6:30 AM BBC World Service 7:00 AM NPR's Morning Edition NPR's Morning Edition NPR's Morning Edition NPR's Morning Edition NPR's Morning Edition On Being 7:30 AM 8:00 AM 8:30 AM NPR's Weekend Edition NPR's Weekend Edition 9:00 AM NPR's ME - 09:51 NPR's ME - 09:51 NPR's ME - 09:51 NPR's ME - 09:51 NPR's ME - 09:51 9:30 AM Marketplace MMR Marketplace MMR Marketplace MMR Marketplace MMR Marketplace MMR 10:00 AM This American Life Wait Wait Don't Tell Me 10:30 AM Diane Rehm Show Diane Rehm Show Diane Rehm Show Diane Rehm Show Diane Rehm Show 11:00 AM Moth Radio Hour Best of Car Talk 11:30 AM 12:00 PM Studio 360 Fresh Air Fresh Air Fresh Air Fresh Air Fresh Air This American Life 12:30 PM 1:00 PM Snap Judgment Radio Lab 1:30 PM Here and Now Here and Now Here and Now Here and Now Here and Now 2:00 PM With Good Reason TED Radio Hour 2:30 PM 3:00 PM BackStory The World The World The World The World Science Friday Moth Radio Hour 3:30 PM 4:00 PM Travel with Rick Steves Snap Judgment 4:30 PM NPR's All Things NPR's All Things NPR's All Things NPR's All Things NPR's All Things 5:00 PM Your Weekly Constitutional Considered Considered Considered Considered Considered Reveal 5:30 PM 6:00 PM NPR's Weekend ATC NPR's Weekend ATC 6:30 PM Marketplace Marketplace Marketplace Marketplace Marketplace 7:00 PM 7:30 PM On Point On Point On Point On Point On Point 8:00 PM 8:30 PM 9:00 PM 9:30 PM 10:00 PM 10:30 PM BBC World Service BBC -

Montgomery County, Va

MONTGOMERY COUNTY, VA www.NewRiverValleyVA.org/Our-Region/Montgomery-County-VA/ Montgomery County, VA which includes the towns of Blacksburg and Christiansburg, benefits from the energy of young professionals, cutting-edge technology companies, downtowns bustling with students, and the abundance of resources offered through Virginia Tech, the area’s largest employer. The retail environment in the two towns provides a wide range of offerings, from unique boutique experiences to big box merchandise. Montgomery County, VA offers the benefits of a small urban community with easy access to outdoor recreation that provides unmatched beauty for any mountain lover. POPULATION: BACHELOR’S DEGREE EMPLOYMENT: 97,653 OR HIGHER: 50% 48,801 WHAT MONTGOMERY COUNTY IS KNOWN FOR: TECHNOLOGY SHOPPING VIRGINIA TECH COMMUNITY & DINING Located in Blacksburg, Virginia Due to lower operation costs and Montgomery County has become Tech is the Commonwealth’s a higher quality of life in the NRV a hot spot for shopping and dining. largest land grant university. This compared to other tech hubs, IT From big box retailers to unique world-renowned institution boasts and digital creative flourishes in boutique experiences, you can find cutting-edge research opportunities Montgomery County. Cultural, what you need in Montgomery for students and local businesses. social, and outdoor opportunities County. If you’re looking for Plus, it churns out a steady stream abound making this a perfect something to eat, enjoy one of the of talent for area employers. Virginia location for talent. Home to many local restaurants, wineries, Tech’s presence also helps cultivate Rackspace, FoxGuard Solutions, or breweries that offer top-notch an elevated arts, music, and festival Venveo, and more, it’s becoming dining experiences for you, and scene.