Understanding the Meaning of Greek Temples' Orientations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

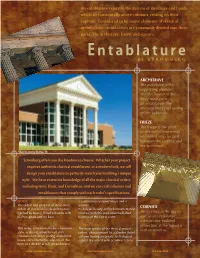

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

The Paroxysmal Activity at Stromboli Volcano in 2019–2021

geosciences Article The Monitoring of CO2 Soil Degassing as Indicator of Increasing Volcanic Activity: The Paroxysmal Activity at Stromboli Volcano in 2019–2021 Salvatore Inguaggiato 1,* , Fabio Vita 1 , Marianna Cangemi 2 , Claudio Inguaggiato 3,4 and Lorenzo Calderone 1 1 Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Sezione di Palermo, Via Ugo La Malfa, 90146 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] (F.V.); [email protected] (L.C.) 2 Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra e del Mare, Via Archirafi 36, 90123 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] 3 Departamento de Geología, Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada, Baja California (CICESE), Carretera Ensenada-Tijuana 3918, 22860 Ensenada, Mexico; [email protected] 4 Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Sezione di Bologna, Via Donato Creti 12, 40128 Bologna, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-091-6809435 Abstract: Since 2016, Stromboli volcano has shown an increase of both frequency and energy of the volcanic activity; two strong paroxysms occurred on 3 July and 28 August 2019. The paroxysms were followed by a series of major explosions, which culminated on January 2021 with magma overflows and lava flows along the Sciara del Fuoco. This activity was monitored by the soil CO2 flux network of Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), which highlighted significant changes Citation: Inguaggiato, S.; Vita, F.; before the paroxysmal activity. The CO2 flux started to increase in 2006, following a long-lasting Cangemi, M.; Inguaggiato, C.; positive trend, interrupted by short-lived high amplitude transients in 2016–2018 and 2018–2019. Calderone, L. The Monitoring of CO2 Soil Degassing as Indicator of This increasing trend was recorded both in the summit and peripheral degassing areas of Stromboli, Increasing Volcanic Activity: The indicating that the magmatic gas release affected the whole volcanic edifice. -

European Commission

C 18/24 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union 20.1.2020 OTHER ACTS EUROPEAN COMMISSION Publication of an application for amendment of a specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 105 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council (2020/C 18/08) This publication confers the right to oppose the application pursuant to Article 98 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council (1) within two months from the date of this publication. REQUEST FOR AMENDMENT TO THE PRODUCT SPECIFICATION ‘MENFI’ PDO-IT-A0786-AM02 Date of application: 29.9.2014 1. Rules applicable to the amendment Article 105 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 – Non-minor modification 2. Description and reasons for amendment 2.1. Article 1 of the product specification. Designation and wines/Categories. Amendment to the product specification and single document Description a) the category (4) Sparkling wine has been added, comprising: — Spumante bianco, including with indication of one of the following grape varieties: Chardonnay, Grecanico, Chenin Blanc and Moscato Bianco; — Spumante rosato; b) the category (15) Wine from raisined grapes has been extended to cover also: — Bianco passito; — Rosso passito; Reasons The newly introduced categories, sparkling wine and wine from raisined grapes, are well established products in the relevant area. There has been a lot of experimentation in the area where the DOC Menfi is produced over the last 20 years and the intention of this amendment is therefore to reflect the new reality. -

Creating the Past: Roman Villa Sculptures

��������������������������������� Creating the Past: Roman Villa Sculptures Hadrian’s pool reflects his wide travels, from Egypt to Greece and Rome. Roman architects recreated old scenes, but they blended various elements and styles to create new worlds with complex links to ideal worlds. Romans didn’t want to live in the past, but they wanted to live with it. Why “creating” rather than “recreating” the past? Most Roman sculpture was based on Greek originals 100 years or more in the past, but these Roman copies, in their use & setting, created a view of the past as the Romans saw it. In towns, such as Pompeii, houses were small, with little room for large gardens (the normal place for statues), so sculpture was under life-size and highlighted. The wall frescoes at Pompeii or Boscoreale (as in the reconstructed room at the Met) show us what the buildings and the associated sculptures looked like. Villas, on the other hand, were more expansive, generally sited by the water and had statues, life-size or larger, scattered around the gardens. Pliny’s villas, as he describes them in his letters, show multiple buildings, seemingly haphazardly distributed, connected by porticoes. Three specific villas give an idea of the types the Villa of the Papyri near Herculaneum (1st c. AD), Tiberius’ villa at Sperlonga from early 1st century (described also in CHSSJ April 1988 lecture by Henry Bender), and Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli (2nd cent AD). The Villa of Papyri, small and self-contained, is still underground, its main finds having been reached by tunneling; the not very scientific excavation left much dispute about find-spots and the villa had seen upheaval from the earthquake of 69 as well as the Vesuvius eruption of 79. -

Urban Planning in the Greek Colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia

Urban Planning in the Greek Colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia (8th – 6th centuries BCE) An honors thesis for the Department of Classics Olivia E. Hayden Tufts University, 2013 Abstract: Although ancient Greeks were traversing the western Mediterranean as early as the Mycenaean Period, the end of the “Dark Age” saw a surge of Greek colonial activity throughout the Mediterranean. Contemporary cities of the Greek homeland were in the process of growing from small, irregularly planned settlements into organized urban spaces. By contrast, the colonies founded overseas in the 8th and 6th centuries BCE lacked any pre-existing structures or spatial organization, allowing the inhabitants to closely approximate their conceptual ideals. For this reason the Greek colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia, known for their extensive use of gridded urban planning, exemplified the overarching trajectory of urban planning in this period. Over the course of the 8th to 6th centuries BCE the Greek cities in Sicily and Magna Graecia developed many common features, including the zoning of domestic, religious, and political space and the implementation of a gridded street plan in the domestic sector. Each city, however, had its own peculiarities and experimental design elements. I will argue that the interplay between standardization and idiosyncrasy in each city developed as a result of vying for recognition within this tight-knit network of affluent Sicilian and South Italian cities. This competition both stimulated the widespread adoption of popular ideas and encouraged the continuous initiation of new trends. ii Table of Contents: Abstract. …………………….………………………………………………………………….... ii Table of Contents …………………………………….………………………………….…….... iii 1. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………..……….. 1 2. -

A Journey in Pictures Through Roman Religion

A Journey in Pictures through Roman Religion By Ursula Kampmann, © MoneyMuseum What is god? As far as the Romans are concerned we think we know that all too well from our unloved Latin lessons: Jupiter, Juno, Minerva, the Roman Triad as well as the usual gods of the ancient world, the same as the Greek gods in name and effect. In fact, however, the roots of Roman religion lie much earlier, much deeper, in dark, prehistoric times ... 1 von 20 www.sunflower.ch How is god experienced? – In the way nature works A bust of the goddess Flora (= flowering), behind it blossom. A denarius of the Roman mint master C. Clodius Vestalis, 41 BC Roman religion emerged from the magical world of the simple farmer, who was speechless when faced with the miracles of nature. Who gave the seemingly withered trees new blossom after the winter? Which power made the grain of corn in the earth grow up to produce new grain every year? Which god prevented the black rust and ensured that the weather was fine just in time for the harvest? Who guaranteed safe storage? And which power was responsible for making it possible to divide up the corn so that it sufficed until the following year? Each individual procedure in a farmer's life was broken down into many small constituent parts whose success was influenced by a divine power. This divine power had to be invoked by a magic ritual in order to grant its help for the action. Thus as late as the imperial period, i.e. -

Trapani Palermo Agrigento Caltanissetta Messina Enna

4 A Sicilian Journey 22 TRAPANI 54 PALERMO 86 AGRIGENTO 108 CALTANISSETTA 122 MESSINA 158 ENNA 186 CATANIA 224 RAGUSA 246 SIRACUSA 270 Directory 271 Index III PALERMO Panelle 62 Panelle Involtini di spaghettini 64 Spaghetti rolls Maltagliati con l'aggrassatu 68 Maltagliati with aggrassatu sauce Pasta cone le sarde 74 Pasta with sardines Cannoli 76 Cannoli A quarter of the Sicilian population reside in the Opposite page: province of Palermo, along the northwest coast of Palermo's diverse landscape comprises dramatic Sicily. The capital city is Palermo, with over 800,000 coastlines and craggy inhabitants, and other notable townships include mountains, both of which contribute to the abundant Monreale, Cefalù, and Bagheria. It is also home to the range of produce that can Parco Naturale delle Madonie, the regional natural be found in the area. park of the Madonie Mountains, with some of Sicily’s highest peaks. The park is the source of many wonderful food products, such as a cheese called the Madonie Provola, a unique bean called the fasola badda (badda bean), and manna, a natural sweetener that is extracted from ash trees. The diversity from the sea to the mountains and the culture of a unique city, Palermo, contribute to a synthesis of the products and the history, of sweet and savoury, of noble and peasant. The skyline of Palermo is outlined with memories of the Saracen presence. Even though the churches were converted by the conquering Normans, many of the Arab domes and arches remain. Beyond architecture, the table of today is still very much influenced by its early inhabitants. -

The Greek Presence in Sicily in Ancient Times, The

‘’The Greek presence‘ in Sicily is ancient times’’ THE ANCIENT GREEK TEMPLES When were the temples created? Greek temples in Sicily were built from the 8th century to the 5th B.C. This period is known as ‘’ The period of the colonization’’ Where were the temples built? The temples that Greeks established were built in ‘’The valley of the Greek temples’’ or in the regions ‘’ Agrigento’’ , ‘’ Selinunte’’ , ‘’Segesta’’, ‘’ Syracuse’’. So let’s start presenting the temples The temple of Athena (Syracuse) On the temple of Athena was later built the present cathedral, where the Virgin Mary is worshiped continuously since the 7th century AD. It is a unique complex of limestone Doric portals and "baroque" Renaissance style. Temple in Segesta In Egesta (Segesta) you can admire the Doric temple of the 5th century BC, whose construction was stopped without cause after the completion of the colonnades. Currently standing at charming solitude, on the outskirts of Segesta and contribute valuable information for building arts of the time. In 416 BC Segesta came into conflict with her neighbors from Selinus and in the 415/416 requested assistance to Athenians. The envoys of Athens were so much excited by the magnificent temple and worth that they advocated war against Syracuse and with the enthusiastic speech of Alcibiades the Athenians were destroyed at Porto Grande, Syracuse in 413 BC. The Temple of Concord In Agrigento (Agrigento), the gigantic Doric temple of Concord, which due to its conversion to an early Christian basilica survived almost intact, is one of the impressive buildings that testify the high standard of living, connected with the presence of the colonial Greeks. -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

Ancient Greek Coins

Ancient Greek Coins Notes for teachers • Dolphin shaped coins. Late 6th to 5th century BC. These coins were minted in Olbia on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine. From the 8th century BC Greek cities began establishing colonies around the coast of the Black Sea. The mixture of Greek and native currencies resulted in a curious variety of monetary forms including these bronze dolphin shaped items of currency. • Silver stater. Aegina c 485 – 480 BC This coin shows a turtle symbolising the naval strength of Aegina and a punch mark In Athens a stater was valued at a tetradrachm (4 drachms) • Silver staterAspendus c 380 BC This shows wrestlers on one side and part of a horse and star on the other. The inscription gives the name of a city in Pamphylian. • Small silver half drachm. Heracles wearing a lionskin is shown on the obverse and Zeus seated, holding eagle and sceptre on the reverse. • Silver tetradrachm. Athens 450 – 400 BC. This coin design was very poular and shows the goddess Athena in a helmet and has her sacred bird the Owl and an olive sprig on the reverse. Coin values The Greeks didn’t write a value on their coins. Value was determined by the material the coins were made of and by weight. A gold coin was worth more than a silver coin which was worth more than a bronze one. A heavy coin would buy more than a light one. 12 chalkoi = 1 Obol 6 obols = 1 drachm 100 drachma = 1 mina 60 minas = 1 talent An unskilled worker, like someone who unloaded boats or dug ditches in Athens, would be paid about two obols a day. -

Slope Instability in the Valley of Temples, Agrigento (Sicily)

Giornale di Geologia Applicata 1 (2005) 91 –101, doi: 10.1474/GGA.2005-01.0-09.0009 Slope Instability in the Valley of Temples, Agrigento (Sicily) Cotecchia V.1, Fiorillo F.2, Monterisi L.1, Pagliarulo R.3 1Dipartimento Ingegneria Civile e Ambientale, Politecnico di Bari 2Dipartimento Studi Geologici e Ambientali, Università del Sannio, Benevento 3Istituto di Ricerca per la Protezione Idrogeologica, CNR, Bari ABSTRACT. The town of Agrigento and the surrounding Valley of Temples represents a place of world importance because of the historical, archaeological and artistic value of their monuments. Since ancient time the town planning expansion of Agrigento has been controlled by the particular geological set up of the area and the repeated and extensive instability phenomena The safeguard of this precious cultural heritage is seriously threatened by slope failures including falls, rock topples and rock slides involving the calcarenitic outcrops. While rotational and translational slides occur when failures develop in the clay and sandy-silt soils below the calcarenitic levels, involving wide areas. This paper explains the geological and structural set up, the geotechnical aspects and man-made factors that exert major influence on this phenomena, on the stability of the area and on the basal foundation of the temples, above all of the Juno Temple. Key terms: Slope stability, Clay, Biocalcarenite, Cultural heritage, Agrigento, Italy Introduction valley below, today known as the Valley of the Temples. A mighty boundary wall has existed to defend the city since its The town of Agrigento is set in a physically fragile foundation, today considerable remains of it can be found environment between unstable slopes and ancient structures along its course. -

‐ Classicism of Mies -‐

- Classicism of Mies - Attachment Student: Oguzhan Atrek St. no.: 4108671 Studio: Explore Lab Arch. mentor: Robert Nottrot Research mentor: Peter Koorstra Tech. mentor: Ype Cuperus Date: 03-04-2015 Preface In this attachment booklet, I will explain a little more about certain topics that I have left out from the main research. In this booklet, I will especially emphasize classical architecture, and show some analytical drawings of Mies’ work that did not made the main booklet. 2 Index 1. Classical architecture………………..………………………………………………………. 4 1.1 . Taxis…………..………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 1.2 . Genera…………..……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 1.3 . Symmetry…………..…………………………………………………………………………... 12 2. Case studies…………………………..……………………………………………...…………... 16 2.1 . Mies van der Rohe…………………………………………………………………………... 17 2.2 . Palladio………………………………………………………………………………………….. 23 2.3 . Ancient Greek temple……………………………………………………………………… 29 3 1. Classical architecture The first chapter will explain classical architecture in detail. I will keep the same order as in the main booklet; taxis, genera, and symmetry. Fig. 1. Overview of classical architecture Source: own image 4 1.1. Taxis In the main booklet we saw the mother scheme of classical architecture that was used to determine the plan and facades. Fig. 2. Mother scheme Source: own image. However, this scheme is only a point of departure. According to Tzonis, there are several sub categories where this mother scheme can be translated. Fig. 3. Deletion of parts Source: own image into into into Fig. 4. Fusion of parts Source: own image 5 Fig. 5. Addition of parts Source: own image into Fig. 6. Substitution of parts Source: own image Into Fig. 7. Translation of the Cesariano mother formula Source: own image 6 1.2.