Download (417Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reimagining the Brontës: (Post)Feminist Middlebrow Adaptations and Representations of Feminine Creative Genius, 1996- 2011

Reimagining the Brontës: (Post)Feminist Middlebrow Adaptations and Representations of Feminine Creative Genius, 1996- 2011. Catherine Paula Han Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Literature) Cardiff University 2015 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Ann Heilmann for her unflagging enthusiasm, kindness and acuity in matters academic and otherwise for four years. Working with Professor Heilmann has been a pleasure and a privilege. I am grateful, furthermore, to Dr Iris Kleinecke-Bates at the University of Hull for co-supervising the first year of this project and being a constant source of helpfulness since then. I would also like to acknowledge the assistance of Professor Judith Buchanan at the University of York, who encouraged me to pursue a PhD and oversaw the conception of this thesis. I have received invaluable support, moreover, from many members of the academic and administrative staff at the School of English, Communication and Philosophy at Cardiff University, particularly Rhian Rattray. I am thankful to the AHRC for providing the financial support for this thesis for one year at the University of Hull and for a further two years at Cardiff University. Additionally, I am fortunate to have been the recipient of several AHRC Research and Training Support Grants so that I could undertake archival research in the UK and attend a conference overseas. This thesis could not have been completed without access to resources held at the British Film Institute, the BBC Written Archives and the Brontë Parsonage Museum. I am also indebted to Tam Fry for giving me permission to quote from correspondence written by his father, Christopher Fry. -

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO Elizabeth Filipecki Machado

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO Elizabeth Filipecki Machado “Lado a Lado” - Reflexões sobre a criação do figurino para teledramaturgia Rio de Janeiro 2016 Elizabeth Filipecki Machado “Lado a Lado” - Reflexões sobre a criação do figurino para teledramaturgia Programa de Pós-graduação em Artes Visuais da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Dissertação Final para obtenção do título de Mestre em História e Crítica da Arte. Orientadora: Prof.ª Dr. ª Maria Cristina Volpi Rio de Janeiro 2016 Elizabeth Filipecki Machado LADO A LADO: Reflexões sobre a criação do figurino para teledramaturgia Dissertação de Mestrado submetida ao Programa da Pós-Graduação em Artes Visuais/ Escola de Belas Artes, da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, como parte dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do título de Mestre em Imagem e Cultura. CIP - Catalogação na Publicação M149l Machado, Elizabeth Filipecki Lado a Lado: Reflexões sobre a criação do figurino para a teledramaturgia / Elizabeth Filipecki Machado. -- Rio de Janeiro, 2016. 210 f. Orientadora: Maria Cristina Volpi. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Escola de Belas Artes, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes Visuais, 2016. 1. figurinos de época. 2. teledramaturgia. 3. práticas artísticas. 4. iconografia. 5. Lado a Lado. I. Volpi, Maria Cristina, orient. II. Título. Elaborado pelo Sistema de Geração Automática da UFRJ com os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a). AGRADECIMENTOS Expresso, de modo singelo e carinhoso, minha gratidão a todas as pessoas que me acompanharam nesta breve e desafiadora experiência intelectual, como discente do Programa de Pós-graduação em Artes Visuais da Escola de Belas Artes. Meus agradecimentos aos profissionais da Secretaria Acadêmica, sempre atentos aos prazos e aos protocolos. -

Chawton House Library Fellowships 2016-17

CHAWTON HOUSE LIBRARY FELLOWSHIPS 2016-17 NAMED FELLOWSHIPS Catherine Han (Yablon Fellowship for Brontë Studies) Dr Catherine Paula Han completed her PhD in English Literature at Cardiff University in 2015. She will be undertaking the Yablon Fellowship for Brontë Studies at Chawton House Library in February 2017 to conduct research for a monograph provisionally entitled Reimagining the Brontës: Readers and Reading in Contemporary Middlebrow Women’s Writing. Her publications include: 'The Myth of Anne Brontë', Brontë Studies, forthcoming. 'Bringing Portraits Alive: Catherine Paula Han interviews Andrea Galer, the costume designer for Jane Eyre (BBC, 2006)', Brontë Studies 39.3: 213-24. Gillian Russell (Marilyn Butler Fellowship) Professor Gillian Russell from the University of Melbourne will be taking up her Marilyn Butler Fellowship at Chawton House Library in March 2017. The title of her research project while in residence at Chawton will be 'Making a Scene: Women Writing Private Theatricals, 1750-2004'. A list of Gillian's publications can be found on her university home page: http://shaps.unimelb.edu.au/about/staff/professor-gillian-russell Brianna Robertson-Kirkland (BSECS Fellowship) Dr Brianna E Robertson-Kirkland from the University of Glasgow will take up her BSECS fellowship at Chawton House Library in April 2017. The subject of her research during her residency will be 'Experiences of music lessons: A woman's perspective'. Further information can be found on her university web page: http://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/cca/postgraduateresearchstudents/briannarobertson-kirkland/ Betty Schellenberg (BARS Fellowship) Betty Schellenberg, Professor of English at Simon Fraser University, Canada, will be the BARS visiting fellow at Chawton House Library in May 2017. -

Chapter I Introduction

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Jane Eyre is a phenomenon story that many films are created of it. One of them is the miniseries movie of Jane Eyre on television. It is the adaptation of Charlotta Bronte’s novel on the same name. Susanna white is the director that makes this movie so different with other. It is four sequels with the running time 240 minutes. This movie has the first release date on September 24th, 2006. The worldwide premiere outside of the United Kingdom is in Spain. Before that, this four-part BBC television drama serial adaptation is broadcast in the United Kingdom on BBC One. This movie has improved script from the novel; Sandy Welch helps Charlotta bronte to write the script so dramatic. With the players like Ruth Wilson, Toby Stephens, Georgie Henley, Tara Fitzgerald, Pam Ferris, Claudia Coulter who are act so natural. This film is also supported by people who are behind this film like editing by Jason Krasucki, cinematography by Mike Eley, music by Robert Lane. They are a good teamwork that make this movie could be received by the viewers. And also, Because of the background of the story of Jane Eyre, so this film uses two languages, English and French. Jane Eyre itself, was brought the director, Susanna White, to be a nominator for two Primetime Emmy. 1 2 Susanna White is a British television director. She was born on 1960 in United Kingdom. She is one of two directors on the BBC adaptation of Bleak House (2005). She makes many other films like Nanny McPhee Returns (2010), Lie With Me (2004), Generation Kill: Get Some (2008), Generation Kill: Screwby (2008), Generation Kill: Bomb in the Garden (2008), The Diary of a Nobody (2007). -

Tsuinfo Alert, October 2006

Contents Volume 8, Number 5, October 2006 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Special features Departments Disaster myths and their implications for disaster planning 1 Hazard Mitigation News 4 Do you know the hazard in your backyard? 9 Publications 7 Tsunami glossary (T) 10 Websites 6 Faster tsunami warnings with GPS 11 Conferences/seminars/symposium 8 Tsunami fears and bay development 12 Classes 8 Stop the presses 16 Material added to NTHMP Library 11 IAQ 13 Video Reservations 14 State Emergency Management Offices 12 NTHMP Steering Group Directory 15 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Disaster Myths…First in a Series DISASTER MYTHS AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR DISASTER PLANNING AND RESPONSE By Henry W. Fischer III, Center for Disaster Research & Education, Millersville University of Pennsylvania From: Natural Hazards Observer, v. 31, no. 1, September 2006 http://www.colorado.edu/hazards/o/sept06/sept06.pdf Reprinted with permission NHO Editor’s Note: As recent events have demonstrated, the perpetuation of myths following a disaster is yet another by-product of ineffective planning, education, response, and reporting. To foster awareness and further discussion and action on the issue of disaster myths, the next six Observers will each feature an article related to disaster mythology. The article below represents the first in the series. It served as a general introduction to the topic, explaining what disas- ter myths are and the implication for the acceptance of these myths as truth. The next four articles will address specific myths: panic, dead bodies and disease, looting, and role abandonment. A concluding article will focus on how disaster myths are perpetuated and what can be done to counteract them or avoid perpetuation altogether. -

For Programming One Hour Or More

Outstanding Animated Program (for How I Met Your Mother • CBS • Twentieth Century Fox Programming Less Than One Hour) Steve Olson, Production Designer Susan Eschelbach, Set Decorator Avatar: The Last Airbender • City Of Walls And Secrets • Nickelodeon • Nickelodeon Animation Studio Outstanding Art Direction For A Single-Camera Nominees TBD Series Robot Chicken • Lust For Puppets • Cartoon Network • Deadwood • HBO • Red Board Productions and Paramount ShadowMachine Films Television in association with HBO Entertainment Nominees TBD Maria Caso, Production Designer David Potts, Art Director The Simpsons • The Haw-Hawed Couple • Fox • Gracie Ernie Bishop, Set Decorator Films in association with 20th Century Fox Nominees TBD Heroes • Genesis • NBC • Tailwind Productions in association with NBC Universal Television Studio South Park • Make Love, Not Warcraft • Comedy Central • Curtis A. Schnell, Production Designer Central Productions Daniel J. Vivanco, Art Director Nominees TBD Crista Schneider, Set Decorator SpongeBob SquarePants • Bummer Vacation / Wig Struck Rome • HBO • HBO Entertainment in association with the • Nickelodeon • Nickelodeon Animation Studio in BBC association with United Plankton Pictures, Inc. Joseph Bennett, Production Designer Nominees TBD Anthony Pratt, Production Designer Outstanding Animated Program (for Carlo Serafini, Art Director Programming One Hour Or More) Cristina Onori, Set Decorator Good Wilt Hunting (Foster’s Home For Imaginary Friends) Shark • Teacher’s Pet • CBS • An Imagine Television • Cartoon Network -

Pdf>, Accessed 10 December 2011

FROM SELF-FULFILMENT TO SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched. This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched. FROM SELF-FULFILMENT TO SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST WORK IN EUROPEAN CINEMA FROM THE 1960S TO THE PRESENT EWA MAZIERSKA Berghahnonfilm This open access edition has been made available under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched. Published in 2015 by Berghahn Books www.berghahnbooks.com © 2015 Ewa Mazierska Open access ebook edition published in 2019 All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mazierska, Ewa. From self-fulfilment to survival of the fittest: work in European cinema from the 1960s to the present / Ewa Mazierska. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-78238-486-1 (hardback: alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-78238-487-8 (ebook) 1. Work in motion pictures. 2. Working class in motion pictures. 3. Motion pictures-- Europe--History--20th century. 4. Motion pictures--Europe--History--21st century. I. Title. PN1995.9.L28M39 2015 791.43’6553--dc23 2014029467 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78238-486-1 hardback E-ISBN 978-1-78920-474-2 open access ebook An electronic version of this book is freely available thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. -

Chawton House Library Fellowships 2016-17

CHAWTON HOUSE LIBRARY FELLOWSHIPS 2016-17 NAMED FELLOWSHIPS Catherine Han (Yablon Fellowship for Brontë Studies) Dr Catherine Paula Han completed her PhD in English Literature at Cardiff University in 2015. She will be undertaking the Yablon Fellowship for Brontë Studies at Chawton House Library in February 2017 to conduct research for a monograph provisionally entitled Reimagining the Brontës: Readers and Reading in Contemporary Middlebrow Women’s Writing. Her publications include: 'The Myth of Anne Brontë', Brontë Studies, forthcoming. 'Bringing Portraits Alive: Catherine Paula Han interviews Andrea Galer, the costume designer for Jane Eyre (BBC, 2006)', Brontë Studies 39.3: 213-24. Gillian Russell (Marilyn Butler Fellowship) Professor Gillian Russell from the University of Melbourne will be taking up her Marilyn Butler Fellowship at Chawton House Library in March 2017. The title of her research project while in residence at Chawton will be 'Making a Scene: Women Writing Private Theatricals, 1750-2004'. A list of Gillian's publications can be found on her university home page: http://shaps.unimelb.edu.au/about/staff/professor-gillian-russell Brianna Robertson-Kirkland (BSECS Fellowship) Dr Brianna E Robertson-Kirkland from the University of Glasgow will take up her BSECS fellowship at Chawton House Library in April 2017. The subject of her research during her residency will be 'Experiences of music lessons: A woman's perspective'. Further information can be found on her university web page: http://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/cca/postgraduateresearchstudents/briannarobertson-kirkland/ Betty Schellenberg (BARS Fellowship) Betty Schellenberg, Professor of English at Simon Fraser University, Canada, will be the BARS visiting fellow at Chawton House Library in May 2017. -

Saffron Cullane Costume 0044 (0)7957455901

Saffron Cullane Costume 0044 (0)7957455901 [email protected] Education [email protected] B.A. Honours Costume Interpretation Wimbledon College of art (First class) Features/TV 2019 Censor Director Prano Bailey-Bond Designer Costume designer Saffron Cullane 2019 Little Birds Director Stacie Passon Cutter/Maker Costume designer Jo Thompson 2018 The Capture Director Ben Chanan Buyer Costume designer Hayley Nebauer 2017 Dumbo Director Tim Burton Maker Costume designer Colleen Atwood 2016/17 The Crown 2 Director Various Workroom Supervisor Costume designer Jane Petrie 2016 Justice League Director Zack Snyder Cutter (Batsuit) Costume designer Michael Wilkinson 2015 Bridget Jones Baby Director Sharon Maguire Assistant Costume designer Steven Noble 2015 The Living And The Dead Director Alice Troughton Cutter Costume designer Phoebe DeGaye 2015 King Arthur Director Guy Ritchie Cutter Costume designer Annie Symons 2014/15 Genius Director Michael Grandage Cutter Costume designer Jane Petrie 2014 Nasty (short) Director Prano Bailey-Bond Designer Costume designer Saffron Cullane 2014 Road Games Director Abner Pastel Designer Costume designer Saffron Cullane 2014 Our World War –BBC interactive Directors Scott Rawsthorne/Jon Shaikh Designer Costume designer Saffron Cullane 2014 Suffragette Director Sarah Gavron Maker Costume designer Jane Petrie 2013/14 Exodus Director Ridley Scott Cutter/Maker Costume designer Janty Yates 2013 Cinderella Directors Kenneth Branagh Cutter/Maker Costume designer Sandy Powell 2013 Guardians of the Galaxy Director -

Outstanding Animated Program (For Chris Clements, Directed by Programming Less Than One Hour) Matt Selman, Written By

Scott Brutz, Animation Timer Outstanding Animated Program (for Chris Clements, Directed By Programming Less Than One Hour) Matt Selman, Written by Avatar: The Last Airbender • City Of Walls And Secrets • South Park • Make Love, Not Warcraft • Comedy Central • Nick • Nickelodeon Animation Studio Central Productions Michael Dante DiMartino, Executive Producer Trey Parker, Executive Producer/Directed by/Written by Bryan Konietzko, Executive Producer Matt Stone, Executive Producer Eric Coleman, Executive Producer Anne Garefino, Executive Producer Aaron Ehasz, Co-Executive Producer/Head Writer Frank C. Agnone II, Supervising Producer Tim Hedrick, Written by Kyle McCulloch, Producer Lauren MacMullan, Directed by Eric Stough, Director of Animation Yu Jae Myoung, Animation Director/Timing Director SpongeBob SquarePants • Bummer Vacation / Wig Struck Robot Chicken • Lust For Puppets • Cartoon Network • • Nick • Nickelodeon Animation Studio in association with ShadowMachine Films United Plankton Pictures, Inc. Seth Green, Executive Producer/Writer/Directed by Stephen Hillenburg, Executive Producer Matthew Senreich, Executive Producer/Writer Paul Tibbitt, Supervising Producer Keith Crofford, Executive Producer Tom Yasumi, Animation Director/Timer Mike Lazzo, Executive Producer Alan Smart, Animation Director/Supervising Director/Timer Corey Campodonico, Producer Casey Alexander, Storyboard Director/Written by Alex Bulkley, Producer Chris Mitchell, Storyboard Director/Written by Tom Root, Head Writer Luke Brookshier, Storyboard Director/Written by -

Table of Membership Figures For

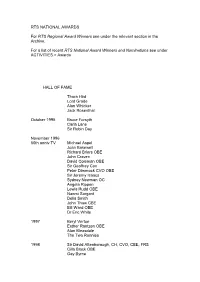

RTS NATIONAL AWARDS For RTS Regional Award Winners see under the relevant section in the Archive. For a list of recent RTS National Award Winners and Nominations see under ACTIVITIES > Awards HALL OF FAME Thora Hird Lord Grade Alan Whicker Jack Rosenthal October 1995 Bruce Forsyth Carla Lane Sir Robin Day November 1996 60th anniv TV Michael Aspel Joan Bakewell Richard Briers OBE John Craven David Coleman OBE Sir Geoffrey Cox Peter Dimmock CVO OBE Sir Jeremy Isaacs Sydney Newman OC Angela Rippon Lewis Rudd OBE Naomi Sargant Delia Smith John Thaw CBE Bill Ward OBE Dr Eric White 1997 Beryl Vertue Esther Rantzen OBE Alan Bleasdale The Two Ronnies 1998 Sir David Attenborough, CH, CVO, CBE, FRS Cilla Black OBE Gay Byrne David Croft OBE Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly Verity Lambert James Morris 1999 Sir Alistair Burnet Yvonne Littlewood MBE Denis Norden CBE June Whitfield CBE 2000 Harry Carpenter OBE William G Stewart Brian Tesler CBE Andrea Wonfor In the Regions 1998 Ireland Gay Byrne Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly James Morris 1999 Wales Vincent Kane OBE Caryl Parry Jones Nicola Heywood Thomas Rolf Harris AM OBE Sir Harry Secombe CBE Howard Stringer 2 THE SOCIETY'S PREMIUM AWARDS The Cossor Premium 1946 Dr W. Sommer 'The Human Eye and the Electric Cell' 1948 W.I. Flach and N.H. Bentley 'A TV Receiver for the Home Constructor' 1949 P. Bax 'Scenery Design in Television' 1950 Emlyn Jones 'The Mullard BC.2. Receiver' 1951 W. Lloyd 1954 H.A. Fairhurst The Electronic Engineering Premium 1946 S.Rodda 'Space Charge and Electron Deflections in Beam Tetrode Theory' 1948 Dr D. -

Bold-Type-CV.Pdf View

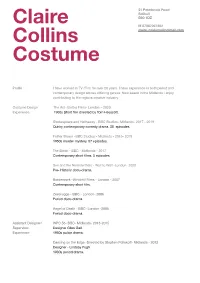

21 Peterbrook Road Solihull Claire B90 1DZ M 07967097262 Collins [email protected] Costume Profile I have worked in TV /Film for over 20 years. I have experience in both period and contemporary design across differing genres. Now based in the Midlands I enjoy contributing to the regions creative industry. Costume Design The Act- Elettra Films- London – 2020 Experience. 1960s Short film directed by Tom Hesscott. Shakespeare and Hathaway - BBC Studios- Midlands- 2017 - 2019 Quirky contemporary comedy drama. 30 episodes. Father Brown -BBC Studios - Midlands - 2015- 2019 1950s murder mystery. 57 episodes. The Break - BBC - Midlands - 2017 Contemporary short films. 5 episodes Sex and the Neanderthals - Wall to Wall -London- 2008 Pre- Historic docu-drama. Borderwork -Windmill Films - London - 2007 Contemporary short film. Zeebrugge - BBC - London- 2006 Period docu-drama. Angel of Death - BBC- London -2006 Period docu-drama. Assistant Designer/ WPC 56- BBC- Midlands- 2013-2015 Supervisor Designer Giles Gail. Experience 1950s police drama. Dancing on the Edge -Directed by Stephen Poliakoff- Midlands - 2013 Designer - Lindsay Pugh 1930s period drama. Hustle - Kudos- London / Midlands 2004-2012 Designer- Richard Cook Ian Macaulay Contemporary drama. Miss Marple- ITV- London - 2004-2013 Designer - Sheena Napier 1950s murder mystery. Miss Austen Regrets- BBC Film - London - 2007 Designer - Andrea Galer Georgian period drama. Costume Assistant Jane Eyre- BBC- London - 2006 Experience Designer - Andrea Galer Victorian mini series. Scenes of a Sexual Nature - Directed by Ed Blum- London - 2006 Designer - Jo Thompson Contemporary feature film. Starter for 10- HBO/Playtone/Neal street productions/BBC films- London -2006 Designer - Charlotte Morris 1980s Feature Film. Bleak House - BBC- London- 2005 Designer - Andrea Galer Victorian Mini Series.