Tiananmen at 30 Event Transcript Fairbank Center for Chinese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

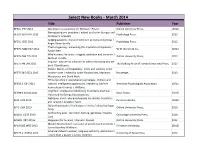

Select New Books - March 2014 Title Publisher Year BF321 .P67 2012 Attention in a Social World / Michael I

Select New Books - March 2014 Title Publisher Year BF321 .P67 2012 Attention in a social world / Michael I. Posner. Oxford University Press, c2012. Stereotyping and prejudice / edited by Charles Stangor and BF323.S63 S747 2013 Psychology Press, 2013. Christian S. Crandall. Judging passions : moral emotions in persons and groups / BF531 .G56 2012 Psychology Press, 2012. Roger Giner-Sorolla. That's disgusting : unraveling the mysteries of repulsion / BF575.A886 H47 2012 W.W. Norton & Co., c2012. Rachel Herz. Why humans like to cry : tragedy, evolution and the brain / BF575.C88 T75 2012 Oxford University Press, 2012. Michael Trimble. Impulse : why we do what we do without knowing why we BF575.I46 L49 2013 The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013. do it / David Lewis. Shame, blame, and culpability : crime and violence in the BF575.S45 S522 2013 modern state / edited by Judith Rowbotham, Marianna Routledge, 2013. Muravyeva, and David Nash. Ethical practice in operational psychology : military and BF636.3 .E84 2011 national intelligence applications / edited by Carrie H. American Psychological Association, c2011. Kennedy and Thomas J. Williams. Ungifted : intelligence redefined / Scott Barry Kaufman ; BF698.9.I6 K38 2013 Basic Books, [2013] illustrated by George Doutsiopoulos. Righteous mind : why good people are divided by politics BJ45 .H25 2012 Pantheon Books, c2012. and religion / Jonathan Haidt. Oxford handbook of the history of ethics / edited by Roger BJ71 .O94 2013 Oxford University Press, 2013. Crisp. Confronting evils : terrorism, torture, genocide / Claudia BJ1401 .C293 2010 Cambridge University Press, 2010. Card. BJ1481 .R87 2012x Happiness for humans / Daniel C. Russell. Oxford University Press, 2012. Muslim Brotherhood : evolution of an Islamist movement / BP10.I385 W53 2013 Princeton University, [2013] Carrie Rosefsky Wickham. -

Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989

Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989 Geremie Barmé1 There should be room for my extremism; I certainly don’t demand of others that they be like me... I’m pessimistic about mankind in general, but my pessimism does not allow for escape. Even though I might be faced with nothing but a series of tragedies, I will still struggle, still show my opposition. This is why I like Nietzsche and dislike Schopenhauer. Liu Xiaobo, November 19882 I FROM 1988 to early 1989, it was a common sentiment in Beijing that China was in crisis. Economic reform was faltering due to the lack of a coherent program of change or a unified approach to reforms among Chinese leaders and ambitious plans to free prices resulted in widespread panic over inflation; the question of political succession to Deng Xiaoping had taken alarming precedence once more as it became clear that Zhao Ziyang was under attack; nepotism was rife within the Party and corporate economy; egregious corruption and inflation added to dissatisfaction with educational policies and the feeling of hopelessness among intellectuals and university students who had profited little from the reforms; and the general state of cultural malaise and social ills combined to create a sense of impending doom. On top of this, the government seemed unwilling or incapable of attempting to find any new solutions to these problems. It enlisted once more the aid of propaganda, empty slogans, and rhetoric to stave off the mounting crisis. University students in Beijing appeared to be particularly heavy casualties of the general malaise. -

Standoff at Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: the Making of Goddess of Democracy

2019/4/23 Standoff At Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy 更多 创建博客 登录 Standoff At Tiananmen How Chinese Students Shocked the World with a Magnificent Movement for Democracy and Liberty that Ended in the Tragic Tiananmen Massacre in 1989. Relive the history with this blog and my book, "Standoff at Tiananmen", a narrative history of the movement. Home Days People Documents Pictures Books Recollections Memorials Monday, May 30, 2011 "Standoff at Tiananmen" English Language Edition Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy Click on the image to buy at Amazon "Standoff at Tiananmen" Chinese Language Edition On May 30, 1989, the statue Goddess of Democracy was erected at Tiananmen Square and became one of the lasting symbols of the 1989 student movement. The following is a re-telling of the making of that statue, originally published in the book Children of Dragon, by a sculptor named Cao Xinyuan: Nothing excites a sculptor as much as seeing a work of her own creation take shape. But although I was watching the creation of a sculpture that I had had no part in making, I nevertheless felt the same excitement. It was the "Goddess of Democracy" statue that stood for five days in Tiananmen Square. Until last year I was a graduate student at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, where the sculpture was made. I was living there when these events took place. 点击图像去Amazon购买 Students and faculty of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, which is located only a short distance from Tiananmen Square, had from the beginning been actively involved in the demonstrations. -

The Dimming of a Chinese Strongman's Aura Introduction A

The dimming of a Chinese strongman’s aura 01 June, 2020 | GS-II | International Relations | GS PAPER 2 | INTERNATIONAL ISSUES | CHINA | CHINA OBOR | INDIA AND CHINA The dimming of a Chinese strongman’s aura By, Sujan R. Chinoy, a China specialist and former Ambassador, is currently the Director General of the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. The views expressed are personal Introduction # To the outside world, China seeks to project a picture of monolithic unity behind President Xi Jinping’s highly centralised leadership. However, media tropes point to a greater scrutiny of his role and leadership style, especially during the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. # Reports have surfaced alleging delays in reporting facts, conflicting instructions and tight censorship. # Observers have drawn parallels between Mr. Xi and his powerful predecessors, Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, perhaps a tad unfairly to both the iconic architects of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). A timeline of change Mao # Mao presided over the founding of the PRC in 1949. # He consolidated his leadership during the Long March in the mid-1930s. Despite his many detractors, he remained the undisputed leader of China until his death on September 9, 1976 even if, towards the end, it was the Gang of Four, led by his wife Jiang Qing, which had usurped power in his name. # Mao banished his adversaries frequently, whether it was Liu Shaoqi, Lin Biao, or even Deng Xiaoping. # Mao’s reign after the founding of the PRC lasted 27 years. By comparison, the 67-year-old Xi Jinping has been at the helm for just under eight years. -

Tragic Anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Protests and Massacre

TRAGIC ANNIVERSARY OF THE 1989 TIANANMEN SQUARE PROTESTS AND MASSACRE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 3, 2013 Serial No. 113–69 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 81–341PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:13 Nov 03, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_AGH\060313\81341 HFA PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DANA ROHRABACHER, California Samoa STEVE CHABOT, Ohio BRAD SHERMAN, California JOE WILSON, South Carolina GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey TED POE, Texas GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MATT SALMON, Arizona THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BRIAN HIGGINS, New York JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina KAREN BASS, California ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts MO BROOKS, Alabama DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island TOM COTTON, Arkansas ALAN GRAYSON, Florida PAUL COOK, California JUAN VARGAS, California GEORGE HOLDING, North Carolina BRADLEY S. -

Testimony of Zhou Fengsuo, President Humanitarian China and Student Leader of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Demonstrations

Testimony of Zhou Fengsuo, President Humanitarian China and student leader of the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations Congressman McGovern, Senator Rubio, Members of Congress, thank you for inviting me to speak in this special moment on the 30th anniversary of Tiananmen Massacre. As a participant of the 1989 Democracy Movement and a survivor of the Massacre started in the evening of June 3rd, it is both my honor and duty to speak, for these who sacrificed their lives for the freedom and democracy of China, for the movement that ignited the hope of change that was so close, and for the last 30 years of indefatigable fight for truth and justice. I was a physics student at Tsinghua University in 1989. The previous summer of 1988, I organized the first and only free election of the student union of my department. I was amazed and encouraged by the enthusiasm of the students to participate in the process of self-governing. There was a palpable sense for change in the college campuses. When Hu Yaobang died on April 15, 1989. His death triggered immediately widespread protests in top universities of Beijing, because he was removed from the position of the General Secretary of CCP in 1987 for his sympathy towards the protesting students and for being too open minded. The next day I went to Tiananmen Square to offer a flower wreath with my roommates of Tsinghua University. To my pleasant surprise, my words on the wreath was published the next day by a national official newspaper. We were the first group to go to Tiananmen Square to mourn Hu Yaobang. -

Wikileaks Advisory Council

1 WikiLeaks Advisory Council 2 Hi everyone, My name is Tom Dalo and I am currently a senior at Fairfield. I am very excited to Be chairing the WikiLeaks Advisory Council committee this year. I would like to first introduce myself and tell you a little Bit about myself. I am from Allendale, NJ and I am currently majoring in Accounting and Finance. First off, I have been involved with the Fairfield University Model United Nations Team since my freshman year when I was a co-chair on the Disarmament and International Security committee. My sophomore year, I had the privilege of Being Co- Secretary General for FUMUN and although it was a very time consuming event, it was truly one of the most rewarding experiences I have had at Fairfield. Last year I was the Co-Chair for the Fukushima National Disaster Committee along with Alli Scheetz, who filled in as chair for the committee as I was unaBle to attend the conference. Aside from my chairing this committee, I am currently FUMUN’s Vice- President. In addition to my involvement in the Model UN, I am a Tour Ambassador Manager, and a Beta Alpha Psi member. I love the outdoors and enjoy skiing, running, and golfing. I am from Allendale, NJ and I am currently majoring in Accounting and Finance. Some of you may wonder how I got involved with the Model United Nations considering that I am a business student majoring in Accounting and Finance. Model UN offers any student, regardless of their major, a chance to improve their puBlic speaking, enhance their critical thinking skills, communicate Better to others as well as gain exposure to current events. -

Missing Lawyer at Risk of Torture: Jiang Tiangyong

Further information on UA: 148/17 Index: ASA 17/6838/2017 China Date: 28 July 2017 URGENT ACTION ACTIVISTS ARRESTED FOR TIANANMEN COMMEMORATION Two activists, Ding Yajun and Shi Tingfu, have been formally charged with “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” for commemorating the 28th anniversary of the Tiananmen crackdown. Hu Jianguo, another activist involved in the commemoration activities, has been missing since 27 June 2017. Ding Yajun was detained by police in Beijing on 12 June 2017 after she had posted a photo online of her posing at the Tiananmen Square in Beijing together with other petitioners on 4 June 2017 to commemorate the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown. She was criminally detained at Xicheng District Detention Centre in Beijing for one month until she was transferred to Hegang City Detention Centre in Heilongjiang, the province where she currently lives. Ding Yajun was formally arrested for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” on 12 July and will be tried on 31 July 2017. Hu Jianguo, a petitioner from Shanghai who also joined the same photo action, has been missing since 27 June. Shi Tingfu was criminally detained, on suspicion of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble”, the day after he made a speech in front of the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall on 4 June 2017 while wearing a shirt with the phrase “Don’t forget June 4”. He was formally arrested on 4 July for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” and his application for bail was rejected by authorities. His lawyer has visited him at the Yuhuatai District Detention Centre in Nanjing detention centre four times since his detention. -

Digital Authoritarianism and the Global Threat to Free Speech Hearing

DIGITAL AUTHORITARIANISM AND THE GLOBAL THREAT TO FREE SPEECH HEARING BEFORE THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 26, 2018 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available at www.cecc.gov or www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 30–233 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 VerDate Nov 24 2008 12:25 Dec 16, 2018 Jkt 081003 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\USERS\DSHERMAN1\DESKTOP\VONITA TEST.TXT DAVID CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Senate House MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Chairman CHRIS SMITH, New Jersey, Cochairman TOM COTTON, Arkansas ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina STEVE DAINES, Montana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TODD YOUNG, Indiana TIM WALZ, Minnesota DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TED LIEU, California JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon GARY PETERS, Michigan ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Not yet appointed ELYSE B. ANDERSON, Staff Director PAUL B. PROTIC, Deputy Staff Director (ii) VerDate Nov 24 2008 12:25 Dec 16, 2018 Jkt 081003 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 C:\USERS\DSHERMAN1\DESKTOP\VONITA TEST.TXT DAVID C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS Page Opening Statement of Hon. Marco Rubio, a U.S. Senator from Florida; Chair- man, Congressional-Executive Commission on China ...................................... 1 Statement of Hon. Christopher Smith, a U.S. Representative from New Jer- sey; Cochairman, Congressional-Executive Commission on China .................. 4 Cook, Sarah, Senior Research Analyst for East Asia and Editor, China Media Bulletin, Freedom House ..................................................................................... 6 Hamilton, Clive, Professor of Public Ethics, Charles Sturt University (Aus- tralia) and author, ‘‘Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia’’ ............ -

The Memory of Tiananmen 1989

Timeline The Memory of Tiananmen 1989 The spring of 1989 saw the largest pro-democracy demonstration in the history of China's communist regime. The following timeline tracks how the protests began in April among university students in Beijing, spread across the nation, and ended on June 4 with a final deadly assault by an estimated force of 300,000 soldiers from People's Liberation Army (PLA). Throughout these weeks, China's top leaders were deeply divided over how to handle the unrest, with one faction advocating peaceful negotiation and another demanding a crackdown. Excerpts from their statements, drawn from The Tiananmen Papers, reveal these internal divisions. Related Features April 17 Newspaper Headlines About the "Tank Man" Mourners flock to Tiananmen Gate. Eyewitness To Tiananmen Spring Tens of thousands of university students begin gathering spontaneously in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, The Legacy of June Fourth the nation's symbolic central space. They come to mourn the death of Hu Yoabang, former General Secretary of the Communist Party. Hu had been a symbol to them of anti-corruption and political reform. In his name, the students call for press freedom and other reforms. April 18 - 21 Unrest Spreads Demonstrations escalate in Beijing and spread to other cities and universities. Workers and officials join in with complaints about inflation, salaries and housing. Party leaders fear the demonstrations might lead to chaos and rebellion. One group, lead by Premier Li Peng, second- ranking in the Party hierarchy, suspects "black -

Inventory of the Collection Chinese People's Movement, Spring 1989 Volume Ii: Audiovisual Materials, Objects and Newspapers

International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ INVENTORY OF THE COLLECTION CHINESE PEOPLE'S MOVEMENT, SPRING 1989 VOLUME II: AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS, OBJECTS AND NEWSPAPERS at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ For a list of the Working Papers published by Stichting beheer IISG, see page 181. International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ Frank N. Pieke and Fons Lamboo INVENTORY OF THE COLLECTION CHINESE PEOPLE'S MOVEMENT, SPRING 1989 VOLUME II: AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS, OBJECTS AND NEWSPAPERS at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) Stichting Beheer IISG Amsterdam 1991 International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ CIP-GEGEVENS KONINLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Pieke, Frank N. Inventory of the Collection Chinese People's Movement, spring 1989 / Frank N. Pieke and Fons Lamboo. - Amsterdam: Stichting beheer IISG Vol. II: Audiovisual Materials, Objects and Newspapers at the International Institute of Social History (IISH). - (IISG-werkuitgaven = IISG-working papers, ISSN 0921-4585 ; 16) Met reg. ISBN 90-6861-060-0 Trefw.: Chinese volksbeweging (collectie) ; IISG ; catalogi. c 1991 Stichting beheer IISG All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar worden gemaakt door middel van druk, fotocopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. Printed in the Netherlands International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents v Preface vi 1. -

Tiananmen Square

The Tiananmen Legacy Ongoing Persecution and Censorship Ongoing Persecution of Those Seeking Reassessment .................................................. 1 Tiananmen’s Survivors: Exiled, Marginalized and Harassed .......................................... 3 Censoring History ........................................................................................................ 5 Human Rights Watch Recommendations ...................................................................... 6 To the Chinese Government: .................................................................................. 6 To the International Community ............................................................................. 7 Ongoing Persecution of Those Seeking Reassessment The Chinese government continues to persecute those who seek a public reassessment of the bloody crackdown. Chinese citizens who challenge the official version of what happened in June 1989 are subject to swift reprisals from security forces. These include relatives of victims who demand redress and eyewitnesses to the massacre and its aftermath whose testimonies contradict the official version of events. Even those who merely seek to honor the memory of the late Zhao Ziyang, the secretary general of the Communist Party of China in 1989 who was sacked and placed under house arrest for opposing violence against the demonstrators, find themselves subject to reprisals. Some of those still targeted include: Ding Zilin and the Tiananmen Mothers: Ding is a retired philosophy professor at