Reconfiguring India: Narrating the Nation Through Great Men Biopics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Movies, Brand Australia and the Marketing of Australian Cosmopolitanism

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2013 Indian movies, brand Australia and the marketing of Australian cosmopolitanism Andrew Hassam University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hassam, Andrew, "Indian movies, brand Australia and the marketing of Australian cosmopolitanism" (2013). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 919. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/919 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Indian movies, brand Australia and the marketing of Australian cosmopolitanism Abstract Indian movies shot overseas have attracted the attention of not only advertising agencies keen to see their clients' brands appearing on-screen, but also government tourism commissions eyeing India's growing middle classes as potential visitors. Australian federal and state governments offer Indian film producers financial incentives to film in Australia, and Australian cities now regularly supply Indian movies with backdrops of upmarket shopping malls, stylish apartments and exclusive restaurants. Yet in helping to project the lifestyle fantasies of India's new middle classes, Australian government agencies are supporting an Indian view of Australia. While this image may attract Indian tourists to Australia, it presumes Australia is culturally White and British, and as a result Australian agencies market an Australian cosmopolitanism defined not in terms of cultural diversity but in terms of the availability of global brands. -

Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba

Om Sri Sai Ram BHAGAVAT GITA VAHINI By Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Greetings Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba is the Sanathana Sarathi, the timeless charioteer, who communicated the Geetha Sastra to Adithya and helped Manu and king Ikshwaku to know it; He was the charioteer of Arjuna during the great battle between good and evil fought out at Kurukshetra. When the rider, Arjuna, was overcome with grief at the prospect of the fight, Krishna instructed him in the science of recognising one's oneness with all, and removed the grief and the fear. He is the charioteer even now, for every one of us; let me greet you as a fellow-sufferer and a fellow-disciple. We have but to recognise Him and accept Him in that role, holding the reins of discrimination and flourishing the whip of detachment, to direct the horses of the senses along the path of Sathya, asphalted by Dharma and illumined by Prema towards the goal of Shanthi. Arjuna accepted Him in that role; let us do likewise. When worldly attachment hinders the path of duty, when ambition blinds the eyes of sympathy, when hate shuts out the call of love, let us listen to the Geetha. He teaches us from the chariot whereon He is installed. Then He showers His grace, His vision and His power, and we are made heroes fit to fight and win. This precious book is not a commentary or summary of the Geetha that was taught on the field of Kurukshetra. We need not learn any new language or read any old text to imbibe the lesson that the Lord is eager to teach us now, for victory in the battle we are now waging. -

Androcentrism in Indian Sports

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 Androcentrism in Indian sports Bijit Das [email protected] Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of Sociology Dibrugarh University Dibrugarh, Assam, India 786004 Abstract The personality of every individual concerning caste, creed, religion, gender in India depends on the structures of society. The society acts as a ladder in diffusing stereotypes from generation to generation which becomes a fundamental constructed ideal type for generalizing ideas on what is masculine or feminine. The gynocentric and androcentric division of labor in terms of work gives more potential for females in household works but not as the position of males. This paper is more concentrated on the biases of women in terms of sports and games which are male- dominated throughout the globe. The researcher looks at the growing stereotypes upon Indian sports as portrayed in various Indian cinemas. Content analysis is carried out on the movies Dangal and Chak de India to portray the prejudices shown by the Indian media. A total of five non-fictional sports movies are made in India in the name of Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013), Paan Singh Tomar(2012), MS Dhoni: An untold story(2016), Azhar(2016), Sachin: A billion dreams(26 May 2017) are on male sportsperson whereas only two movies are on women, namely Mary Kom (2014), Dangal(2017). This indicates that male preference is more than female in Indian media concerning any sports. The acquaintance of males in every sphere of life is being carried out from ancient to modern societies. This paper will widen the perspectives of not viewing society per media but to the independence and equity of both the sex in every sphere of life. -

Recruiter's Handbook 2020

Recruiter’s Handbook 2020 VISION To create a state-of-the-art institution that sets new standards of world-class education in film, communication and creative arts. MISSION Benchmarking quality, inspiring innovation, encouraging creativity & moulding minds, by leading from the front in the field of film, media and entertainment education. ONE OF THE TEN BEST FILM SCHOOLS IN THE WORLD - THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER Degree & Diploma 5.5 ACRE programmes CAMPUS acceredited by the TISS 1300+ 2200+ STUDENTS Media & Film industry Alumni campus SCHOOL OF EVENT MANAGEMENT Subhash Ghai Founder & Chairman, Whistling Woods International Chairman, Mukta Arts Limited Member, Executive Committee, Film & Television Producers Guild of India Member, United Producers Forum Education Evangelist Karamveer Chakra Awardee Chairman, MESC Subhash Ghai is a globally renowned filmmaker having directed 19 films over a four-decade career, with 14 of them being blockbusters. Recipient of many national and international awards, he has also been honoured by the United States Senate. He has been a former Chairman of the Entertainment Committee of Trade body CII and also a member of FICCI, NASSCOM and TIE Global & its alliances. He has been invited to address various forums and seminars on corporate governance and the growth of Media & Entertainment industry globally and in India. He is presently serving as the Chairman of Media and Entertainment Skills Council (MESC). Message from the Founder & Chairman My journey as a filmmaker in the Media & Entertainment (M&E) industry has been a long and cherished one. Over the years, the one factor that has grounded me and contributed to my success is the basic film education I received from the film institute I studied in, coupled with my strong desire to learn and re-learn from my days as part of the Indian film industry. -

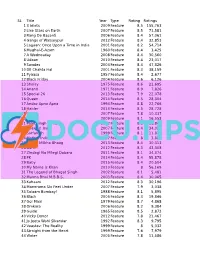

Aspirational Movie List

SL Title Year Type Rating Ratings 1 3 Idiots 2009 Feature 8.5 155,763 2 Like Stars on Earth 2007 Feature 8.5 71,581 3 Rang De Basanti 2006 Feature 8.4 57,061 4 Gangs of Wasseypur 2012 Feature 8.4 32,853 5 Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India 2001 Feature 8.2 54,714 6 Mughal-E-Azam 1960 Feature 8.4 3,425 7 A Wednesday 2008 Feature 8.4 30,560 8 Udaan 2010 Feature 8.4 23,017 9 Swades 2004 Feature 8.4 47,326 10 Dil Chahta Hai 2001 Feature 8.3 38,159 11 Pyaasa 1957 Feature 8.4 2,677 12 Black Friday 2004 Feature 8.6 6,126 13 Sholay 1975 Feature 8.6 21,695 14 Anand 1971 Feature 8.9 7,826 15 Special 26 2013 Feature 7.9 22,078 16 Queen 2014 Feature 8.5 28,304 17 Andaz Apna Apna 1994 Feature 8.8 22,766 18 Haider 2014 Feature 8.5 28,728 19 Guru 2007 Feature 7.8 10,337 20 Dev D 2009 Feature 8.1 16,553 21 Paan Singh Tomar 2012 Feature 8.3 16,849 22 Chakde! India 2007 Feature 8.4 34,024 23 Sarfarosh 1999 Feature 8.1 11,870 24 Mother India 1957 Feature 8 3,882 25 Bhaag Milkha Bhaag 2013 Feature 8.4 30,313 26 Barfi! 2012 Feature 8.3 43,308 27 Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara 2011 Feature 8.1 34,374 28 PK 2014 Feature 8.4 55,878 29 Baby 2015 Feature 8.4 20,504 30 My Name Is Khan 2010 Feature 8 56,169 31 The Legend of Bhagat Singh 2002 Feature 8.1 5,481 32 Munna Bhai M.B.B.S. -

Prabhat Prakashan (In English)

S.No ISBN Title Author MRP Lang. Pages Year Stock Binding 1 9789352664634 Kaka Ke Thahake Kaka Hathrasi 300.00 Hindi 128 2021 10 Hardcover 2 9789352664627 Kaka Ke Golgappe Kaka Hathrasi 450.00 Hindi 184 2021 10 Hardcover 3 9789386870803 Hindu Dharma Mein Vaigyanik Manyatayen K.V. Singh 400.00 Hindi 184 2021 10 Hardcover 4 9789390366842 Ahilyabai (& udaykiran) Vrindavan Lal Verma 700.00 Hindi 352 2021 10 Hardcover 5 9789352669394 Sudha Murty Ki Lokpriya Kahaniyan Sudha Murty 350.00 Hindi 176 2021 10 Hardcover 6 9788173150500 Amarbel Vrindavan Lal Verma 400.00 Hindi 200 2021 10 Hardcover 7 9788173150999 Shreshtha Hasya Vyangya Ekanki Kaka Hatharasi 450.00 Hindi 224 2021 10 Hardcover 8 9789389982664 Mera Desh Badal Raha Hai Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam 500.00 Hindi 224 2021 10 Hardcover 9 9789389982329 Netaji Subhash Ki Rahasyamaya Kahani Kingshuk Nag 350.00 Hindi 176 2021 10 Hardcover 10 9789389982022 Utho! Jago! Aage Barho Sandip Kumar Salunkhe 400.00 Hindi 160 2021 10 Hardcover 11 9789389982718 Champaran Andolan 1917 Ashutosh Partheshwar 400.00 Hindi 184 2021 10 Hardcover 12 9789389982916 Ramayan Ki Kahani, Vigyan Ki Zubani Saroj Bala 400.00 Hindi 206 2021 10 Hardcover 13 9789389982688 Vidyarthiyon Mein Avishkarak Soch Lakshman Prasad 400.00 Hindi 192 2021 10 Hardcover 14 9789390101757 Zimmedari (Responsibility) P.K. Arya 500.00 Hindi 240 2021 10 Hardcover 15 9789389982305 Samaya Prabandhan (Time Management) P.K. Arya 500.00 Hindi 232 2021 10 Hardcover 16 9789389982312 Smaran Shakti (Memory Power) P.K. Arya 400.00 Hindi 216 2021 10 Hardcover 17 9789389982695 Jannayak Atalji (Sampoorn Jeevani) Kingshuk Nag 350.00 Hindi 168 2021 10 Hardcover 18 9789389982671 Positive Thinking Napoleon Hill ; Michael J. -

Retelling the Nation: Narrating the Nation Through Biopics, Preeti

The Asian Conference on Film and Documentary 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan Retelling the Nation: Narrating the Nation through Biopics, Preeti Kumar St. Teresa's College, Ernakulam, India 0209 The Asian Conference on Film and Documentary 2013 Official Conference Proceedings 2013 Abstract Cinema plays a pivotal role in the negotiation and construction of national identity, selectively appropriating history, attempting to forge a sense of commonality in a set of people by evoking a sense of a shared past and by establishing a rupture with ‘others'. One of the means of constructing a nation is through the biopic. Great men biopics chronicle heroic deeds, sacrifice, and lofty moral virtues and either fabricate, or rediscover, and authenticate the myths of the founding fathers and celebrated men. Biopics disseminate the "myth of nationhood" by use of various narrative strategies - such as a glorification of hypermasculinity, structuring binary oppositions in terms of character and thematic concerns, ‘otherness', visualizing national territory, homogenizing a cultural diversity etc. These films become a part of the nationalistic discourse that reflect perceptions of what it means to be "Indian". Bollywood in general and the biopic in particular has moved away from the Mother India mythology and its feminine reading of the nation to produce a particular variant of nationalism. This paper attempts to deconstruct how the nation is simulated, and meanings, such as national pride and national idealism, are mediated to the audience in selected Indian biopics - Sardar, The Legend of Bhagat Singh, Mangal Pandey - The Rising and Bhaag Milkha Bhaag. Key terms: Cinema, biopic, Bollywood, identity, memory, otherness, gendering, simulation/construction. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

Pendidikan Siswa/I

EDISI REVISI 2018 Pendidikan Agama Hindu dan Budi Pekerti Pendidikan Buku pelajaran pendidikan agama Hindu untuk siswa/i tingkat Sekolah Dasar ini disusun sesuai dengan Kurikulum 2013, agar siswa/i aktif dalam proses pembelajaran. Buku ini dilengkapi dengan Agama Hindu kegiatan-kegiatan seperti, berpendapat, kreativitasku, aktivitasku, diskusi dengan orang tua, diskusi di kelas, bermain huruf, teka-teki silang, menceritakan pengalaman, demontrasi dan latih kognitif. Semua kegiatan tersebut bertujuan membantu siswa/i memahami dan mengaplikasikan ajaran agama Hindu dan Budi Pekerti dalam kehidupan. Buku ini dilengkapi glosarium dan ilustrasi guna memotivasi siswa/i gemar membaca, Kelas III SD • menumbuhkan rasa cinta melalui ajaran Tri Parartha, memahami ajaran Hindu melalui tokoh-tokoh dalam Mahābhārata, mengenal ajaran Daivi dan Asuri Sampad dalam Kitab Bhagavadgītā, mengenal nama-nama planet dalam tata surya Hindu serta mencintai budaya Hindu melalui materi Tari Profan dan Tari Sakral. Dengan buku agama Hindu ini, kami berharap siswa/i dapat belajar dengan mudah dalam memahami materi-materi pelajaran pendidikan agama Hindu, sehingga dapat menumbuhkan semangat dan kreativitas dalam meningkatkan Sraddha dan Bhakti siswa/i. Pendidikan Agama Hindu dan Budi Pekerti Agama Pendidikan ZONA 1 ZONA 2 ZONA 3 ZONA 4 ZONA 5 HET RpXX.XXX RpXX.XXX RpXX.XXX RpXX.XXX RpXX.XXX ISBN: SD 978-602-282-224-0 (jilid lengkap) 978-602-282-227-1 (jilid 3) KELAS III Hak Cipta © 2018 pada Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Dilindungi Undang-Undang Disklaimer: Buku ini merupakan buku siswa yang dipersiapkan Pemerintah dalam rangka implementasi Kurikulum 2013. Buku siswa ini disusun dan ditelaah oleh berbagai pihak di bawah koordinasi Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, dan dipergunakan dalam tahap awal penerapan Kurikulum 2013. -

Rebellion of 1857 Was Doomed to Fail, but the Religious and Cultural Tensions It Inflamed Would Ultimately Topple the British Raj by Ron Soodalter

THE INDIAN REBELLION OF 1857 WAS DOOMED TO FAIL, BUT THE RELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL TENSIONS IT INFLAMED WOULD ULTIMATELY TOPPLE THE BRITISH RAJ BY RON SOODALTER On May 9,1857, some 4,000 British soldiers and sepoys—native Indian troops—formed a three-sided hollow square on the parade ground at the Meerut mihtary cantonment, 40 miles northeast of Delhi, to witness punishment. On the fourth side of the square 85 sepoys of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry—Muslims and Hindus, many of them veterans with long years of service—stood at attention as their uniform jackets were stripped from them. The disgraced soldiers, weeping and begging for mercy, were then marched away to imprisonment at hard lahor. The offense for which they had been court-martialed was disobedience—they had refused to load their rifles. or more than 150 years historians percussion cap, bring the hammer to removed from the cartridge, the sides of have maintained that India's First full cock and fire. the bullet should be wetted in the mouth revolt against British rule broke During manufacture the cartridges bejoi e putting it into the barrel; the out at least in part over a gun-—to were coated with beeswax and tallow to saliva will serve the purpose of grease beF precise, the muzzle-loading Pattern protect the powder from the elements, for the time being. 1853 Enfield rifle-musket. Each of the and the bullets were greased to ensure a weapon's paper cartridges contained a proper seal in the barrel. The adjutant- When rumors spread among the precise amount of powder and a .577- general's official 1856 Instruction of caliber Minié ball. -

PDF Version of This Article

INDIA It's never too late... by Paramesh Krishnan Nair Afew years ago, a well-known Indian Reverso Inter-negative" process is prac¬ turned to powder, or after extraction of the film pioneer told me that of the forty tically unknown and all release copies are silver from the nitro-cellulose base, had odd films he had made he con¬ printed from the original negatives. As a been turned into bangles and ladies' sidered that only two or three were worth result, a large number of original negatives handbags. preserving in the National Film Archive of In¬ of highly successful films have been damag¬ One such film was Alam Ara (1 931 , in Hin¬ dia. This in a way reflects the attitude of most ed beyond repair due to indiscriminate di), the first Indian talkie, which is still not of our film-makers to archival preservation of duplication of positive prints, both 35mm traceable. When contacted two years before their films. and 16mm. his death, Ardeshir M. Irani, the maker of The average film-maker in India does not In India the cinema has never been ac¬ this film and the man who brought sound to believe that what he is doing is of any corded high priority. To the intelligentsia and Indian cinema, told us that he had kept some historical consequence, let alone of cultural educationists the cinema was something to reels of the film in his office at the Imperial interest. For him, as for his colleagues be looked down on with contempt and it was Studio (now Jyothi Studio). -

My Favourite Singers

MY FAVOURITE SINGERS 12 01 01 SAMJHAWAN 17 CHALE CHALO 33 BARSO RE 48 JEENA 63 AY HAIRATHE 79 DIL KYA KARE (SAD) 94 SAAJAN JI GHAR AAYE 108 CHHAP TILAK 123 TUM MILE (ROCK) 138 D SE DANCE ARTIST: ARIJIT SINGH, SHREYA GHOSHAL • ALBUM/FILM: HUMPTY SHARMA KI DULHANIA ARTIST: A. R. RAHMAN, SRINIVAS • ALBUM/FILM: LAGAAN ARTIST: SHREYA GHOSHAL, UDAY MAZUMDAR • ALBUM/FILM: GURU ARTIST: SONU NIGAM, SOWMYA RAOH • ALBUM/FILM: DUM ARTIST: ALKA YAGNIK, HARIHARAN • ALBUM/FILM: GURU ARTIST: KUMAR SANU, ALKA YAGNIK • ALBUM/FILM: DIL KYA KARE ARTIST: KAVITA KRISHNAMURTHY, ALKA YAGNIK, KUMAR SANU ARTIST: KAILASH KHER • ALBUM/FILM: KAILASA JHOOMO RE ARTIST: SHAFQAT AMANAT ALI • ALBUM/FILM: TUM MILE ARTIST: VISHAL DADLANI, SHALMALI KHOLGADE, ANUSHKA MANCHANDA 02 ENNA SONA 18 ROOBAROO 34 KHUSHAMDEED 49 WOH PEHLI BAAR 64 AGAR MAIN KAHOON 80 DEEWANA DIL DEEWANA ALBUM/FILM: KUCH KUCH HOTA HAI 109 CHAANDAN MEIN 124 TERE NAINA ALBUM/FILM: HUMPTY SHARMA KI DULHANIA ARTIST: ARIJIT SINGH • ALBUM/FILM: OK JAANU ARTIST: A. R. RAHMAN, NARESH IYER • ALBUM/FILM: RANG DE BASANTI ARTIST: SHREYA GHOSHAL • ALBUM/FILM: GO GOA GONE ARTIST: SHAAN • ALBUM/FILM: PYAAR MEIN KABHI KABHI ARTIST: ALKA YAGNIK, UDIT NARAYAN • ALBUM/FILM: LAKSHYA ARTIST: UDIT NARAYAN, AMIT KUMAR • ALBUM/FILM: KABHI HAAN KABHI NA 95 MAIN ALBELI ARTIST: KAILASH KHER • ALBUM/FILM: KAILASA CHAANDAN MEIN ARTIST: SHAFQAT AMANAT ALI • ALBUM/FILM: MY NAME IS KHAN 139 VELE 03 GERUA 19 TERE BINA 35 BAHARA 50 TUNE MUJHE PEHCHAANA NAHIN 65 KUCH TO HUA HAI 81 KUCH KUCH HOTA HAI ARTIST: KAVITA KRISHNAMURTHY, SUKHWINDER SINGH • ALBUM/FILM: ZUBEIDAA 110 AA TAYAR HOJA 125 AKHIYAN ARTIST: VISHAL DADLANI, SHEKHAR RAVJIANI • ALBUM/FILM: STUDENT OF THE YEAR ARTIST: ARIJIT SINGH, ANTARA MITRA • ALBUM/FILM: DILWALE ARTIST: A.