The Biological Survey of the Barlee-Menzies Study Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Pinaroo Ramsar Site

Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site Disclaimer The Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW (DECC) has compiled the Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. DECC does not accept responsibility for any inaccurate or incomplete information supplied by third parties. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. Readers should seek appropriate advice about the suitability of the information to their needs. © State of New South Wales and Department of Environment and Climate Change DECC is pleased to allow the reproduction of material from this publication on the condition that the source, publisher and authorship are appropriately acknowledged. Published by: Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney PO Box A290, Sydney South 1232 Phone: 131555 (NSW only – publications and information requests) (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au DECC 2008/275 ISBN 978 1 74122 839 7 June 2008 Printed on environmentally sustainable paper Cover photos Inset upper: Lake Pinaroo in flood, 1976 (DECC) Aerial: Lake Pinaroo in flood, March 1976 (DECC) Inset lower left: Blue-billed duck (R. Kingsford) Inset lower middle: Red-necked avocet (C. Herbert) Inset lower right: Red-capped plover (C. Herbert) Summary An ecological character description has been defined as ‘the combination of the ecosystem components, processes, benefits and services that characterise a wetland at a given point in time’. -

Supplementary Materialsupplementary Material

10.1071/BT13149_AC © CSIRO 2013 Australian Journal of Botany 2013, 61(6), 436–445 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Comparative dating of Acacia: combining fossils and multiple phylogenies to infer ages of clades with poor fossil records Joseph T. MillerA,E, Daniel J. MurphyB, Simon Y. W. HoC, David J. CantrillB and David SeiglerD ACentre for Australian National Biodiversity Research, CSIRO Plant Industry, GPO Box 1600 Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. BRoyal Botanic Gardens Melbourne, Birdwood Avenue, South Yarra, Vic. 3141, Australia. CSchool of Biological Sciences, Edgeworth David Building, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. DDepartment of Plant Biology, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801, USA. ECorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Table S1 Materials used in the study Taxon Dataset Genbank Acacia abbreviata Maslin 2 3 JF420287 JF420065 JF420395 KC421289 KC796176 JF420499 Acacia adoxa Pedley 2 3 JF420044 AF523076 AF195716 AF195684; AF195703 Acacia ampliceps Maslin 1 KC421930 EU439994 EU811845 Acacia anceps DC. 2 3 JF420244 JF420350 JF419919 JF420130 JF420456 Acacia aneura F.Muell. ex Benth 2 3 JF420259 JF420036 JF420366 JF419935 JF420146 KF048140 Acacia aneura F.Muell. ex Benth. 1 2 3 JF420293 JF420402 KC421323 JQ248740 JF420505 Acacia baeuerlenii Maiden & R.T.Baker 2 3 JF420229 JQ248866 JF420336 JF419909 JF420115 JF420448 Acacia beckleri Tindale 2 3 JF420260 JF420037 JF420367 JF419936 JF420147 JF420473 Acacia cochlearis (Labill.) H.L.Wendl. 2 3 KC283897 KC200719 JQ943314 AF523156 KC284140 KC957934 Acacia cognata Domin 2 3 JF420246 JF420022 JF420352 JF419921 JF420132 JF420458 Acacia cultriformis A.Cunn. ex G.Don 2 3 JF420278 JF420056 JF420387 KC421263 KC796172 JF420494 Acacia cupularis Domin 2 3 JF420247 JF420023 JF420353 JF419922 JF420133 JF420459 Acacia dealbata Link 2 3 JF420269 JF420378 KC421251 KC955787 JF420485 Acacia dealbata Link 2 3 KC283375 KC200761 JQ942686 KC421315 KC284195 Acacia deanei (R.T.Baker) M.B.Welch, Coombs 2 3 JF420294 JF420403 KC421329 KC955795 & McGlynn JF420506 Acacia dempsteri F.Muell. -

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1 Authors: Jiang, Wei, He, Hua-Jie, Lu, Lu, Burgess, Kevin S., Wang, Hong, et. al. Source: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 104(2) : 171-229 Published By: Missouri Botanical Garden Press URL: https://doi.org/10.3417/2019337 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non - commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/Annals-of-the-Missouri-Botanical-Garden on 01 Apr 2020 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS Volume 104 Annals Number 2 of the R 2019 Missouri Botanical Garden EVOLUTION OF ANGIOSPERM Wei Jiang,2,3,7 Hua-Jie He,4,7 Lu Lu,2,5 POLLEN. 7. NITROGEN-FIXING Kevin S. Burgess,6 Hong Wang,2* and 2,4 CLADE1 De-Zhu Li * ABSTRACT Nitrogen-fixing symbiosis in root nodules is known in only 10 families, which are distributed among a clade of four orders and delimited as the nitrogen-fixing clade. -

FINAL REPORT 2019 Canna Reserve

FINAL REPORT 2019 Canna Reserve This project was supported by NACC NRM and the Shire of Morawa through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program Canna Reserve BioBlitz 2019 Weaving and wonder in the wilderness! The weather may have been hot and dry, but that didn’t stop everyone having fun and learning about the rich biodiversity and conservation value of the wonderful Canna Reserve during the highly successful 2019 BioBlitz. On the 14 - 15 September 2019, NACC NRM together with support from Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions and the Shire of Morawa, hosted their third BioBlitz at the Canna Reserve in the Shire of Morawa. Fifty professional biologists and citizen scientists attended the event with people travelling from near and far including Morawa, Perenjori, Geraldton and Perth. After an introduction and Acknowledgement of Country from organisers Jessica Stingemore and Jarna Kendle, the BioBlitz kicked off with participants separating into four teams and heading out to explore Canna Reserve with the goal of identifying as many plants, birds, invertebrates, and vertebrates as possible in a 24 hr period. David Knowles of Spineless Wonders led the invertebrate survey with assistance from, OAM recipient Allen Sundholm, Jenny Borger of Jenny Borger Botanical Consultancy led the plant team, BirdLife Midwest member Alice Bishop guided the bird survey team and David Pongracz from Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions ran the vertebrate surveys with assistance from volunteer Corin Desmond. The BioBlitz got off to a great start identifying 80 plant species during the first survey with many more species to come and even a new orchid find for the reserve. -

In This Issue: Contents

In this issue: Save the Date… Contents • Next meeting: Monthly Meeting Recap - June ........................ 2 • Wednesday, August 23, 7.30pm August Meeting Teaser: ................................... 5 Plant Profile: ..................................................... 6 Eucalyptus formanii ...................................... 6 Gibberellic acid (GA) ......................................... 8 Upcoming Events ............................................ 10 Contacts:......................................................... 12 Chris Lindorff spoke to us last year on Woodland Birds, including setting up an Upcoming Meetings: area for attracting them. This month, Chris will return and expand on setting up a - September 27 – sanctuary to attract wildlife Bonsai - October 8 – Nature Coming Up... walk thru Brisbane Ranges • Lots of other events, refer to pages 10 and 11 for more… - October 25 – AGM & Flower Table - November 22 – End Of Year & Photo Comp 1 | P a g e Monthly Meeting Recap - June Our first day meeting was held with a result of only 11 members able to attend. I can say with certainty that those who were absent missed out on a fabulous talk by Kathryn FitzGibbon, who is employed by the Melton City Council as a landscape architect. There were plenty of Awww’s as Kathryn showed us her humble beginnings in the garden as she recalled many hours helping her dad as she was growing up. Kathryn continued her love of gardening, formalising it by obtaining a Bachelor of Design and Master of Landscape Architecture at RMIT, although she admitted that it was a course about the ‘feelings’ of plants, and not actually about plants themselves. Her hard work paid off as she was part of a team that won a Gold Medal at the Grand Designs Live Exhibition in 2012 for their structure incorporating succulents. -

Volume 5 Pt 3

Conservation Science W. Aust. 7 (1) : 153–178 (2008) Flora and Vegetation of the banded iron formations of the Yilgarn Craton: the Weld Range ADRIENNE S MARKEY AND STEVEN J DILLON Science Division, Department of Environment and Conservation, Wildlife Research Centre, PO Box 51, Wanneroo WA 6946. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT A survey of the flora and floristic communities of the Weld Range, in the Murchison region of Western Australia, was undertaken using classification and ordination analysis of quadrat data. A total of 239 taxa (species, subspecies and varieties) and five hybrids of vascular plants were collected and identified from within the survey area. Of these, 229 taxa were native and 10 species were introduced. Eight priority species were located in this survey, six of these being new records for the Weld Range. Although no species endemic to the Weld Range were located in this survey, new populations of three priority listed taxa were identified which represent significant range extensions for these taxa of conservation significance. Eight floristic community types (six types, two of these subdivided into two subtypes each) were identified and described for the Weld Range, with the primary division in the classification separating a dolerite-associated floristic community from those on banded iron formation. Floristic communities occurring on BIF were found to be associated with topographic relief, underlying geology and soil chemistry. There did not appear to be any restricted communities within the landform, but some communities may be geographically restricted to the Weld Range. Because these communities on the Weld Range are so closely associated with topography and substrate, they are vulnerable to impact from mineral exploration and open cast mining. -

Honey and Pollen Flora of SE Australia Species

List of families - genus/species Page Acanthaceae ........................................................................................................................................................................34 Avicennia marina grey mangrove 34 Aizoaceae ............................................................................................................................................................................... 35 Mesembryanthemum crystallinum ice plant 35 Alliaceae ................................................................................................................................................................................... 36 Allium cepa onions 36 Amaranthaceae ..................................................................................................................................................................37 Ptilotus species foxtails 37 Anacardiaceae ................................................................................................................................................................... 38 Schinus molle var areira pepper tree 38 Schinus terebinthifolius Brazilian pepper tree 39 Apiaceae .................................................................................................................................................................................. 40 Daucus carota carrot 40 Foeniculum vulgare fennel 41 Araliaceae ................................................................................................................................................................................42 -

Acacia Study Group Newsletter

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia) Inc. ACACIA STUDY GROUP NEWSLETTER Group Leader and Seed Bank Curator Newsletter Editor and Membership Officer Esther Brueggemeier Bill Aitchison 28 Staton Cr, Westlake, Vic 3337 13 Conos Court, Donvale, Vic 3111 Phone 0411 148874 Phone (03) 98723583 Email: [email protected] No. 110 September 2010 ISSN 1035-4638 Contents Page From The Leader Dear Members, From the Leader 1 What a dramatic start to spring we have had down south. Welcome 2 The locals here are wondering if we are ever to see a dry From Members and Readers 2 day again. Melbourne recently braved some of the strongest Origin of Acacias in Australia 2 and most damaging winds in years with gusts up to 100 Acacia scirpifolia 2 km/h and 130 km/h on the Alps while bringing torrential Acacia glaucoptera 3 downpours to much of the state. Despite being one of the Acacia with part red flowers 3 wettest September's this century, I was amazed to see the Banish the winter blues 3 abundance of wattles bursting into full bloom, as if to say, Acacias and Allergies 4 it’s now or never! Those wattles that flower early, flowered Wattle as a symbol of safety 4 in September. Those wattles that flower late, flowered in Insects and Acacias 5 September, turning my entire garden into a glorious blaze of The Germination of Acacia Seeds 6 golden yellow. Myrtle Rust Fungus 9 Books 9 The Australian Plants issue on Acacias is well and truly Correction 10 printed, though I’m sorry to say, has taken a little longer Seed Bank 10 than expected. -

Lake Havasu City Recommended Landscaping Plant List

Lake Havasu City Recommended Landscaping Plant List Lake Havasu City Recommended Landscaping Plant List Disclaimer Lake Havasu City has revised the recommended landscaping plant list. This new list consists of plants that can be adapted to desert environments in the Southwestern United States. This list only contains water conscious species classified as having very low, low, and low-medium water use requirements. Species that are classified as having medium or higher water use requirements were not permitted on this list. Such water use classification is determined by the type of plant, its average size, and its water requirements compared to other plants. For example, a large tree may be classified as having low water use requirements if it requires a low amount of water compared to most other large trees. This list is not intended to restrict what plants residents choose to plant in their yards, and this list may include plant species that may not survive or prosper in certain desert microclimates such as those with lower elevations or higher temperatures. In addition, this list is not intended to be a list of the only plants allowed in the region, nor is it intended to be an exhaustive list of all desert-appropriate plants capable of surviving in the region. This list was created with the intention to help residents, businesses, and landscapers make informed decisions on which plants to landscape that are water conscious and appropriate for specific environmental conditions. Lake Havasu City does not require the use of any or all plants found on this list. List Characteristics This list is divided between trees, shrubs, groundcovers, vines, succulents and perennials. -

Palatability of Plants to Camels (DBIRD NT)

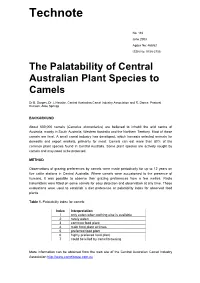

Technote No. 116 June 2003 Agdex No: 468/62 ISSN No: 0158-2755 The Palatability of Central Australian Plant Species to Camels Dr B. Dorges, Dr J. Heucke, Central Australian Camel Industry Association and R. Dance, Pastoral Division, Alice Springs BACKGROUND About 600,000 camels (Camelus dromedarius) are believed to inhabit the arid centre of Australia, mainly in South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. Most of these camels are feral. A small camel industry has developed, which harvests selected animals for domestic and export markets, primarily for meat. Camels can eat more than 80% of the common plant species found in Central Australia. Some plant species are actively sought by camels and may need to be protected. METHOD Observations of grazing preferences by camels were made periodically for up to 12 years on five cattle stations in Central Australia. Where camels were accustomed to the presence of humans, it was possible to observe their grazing preferences from a few metres. Radio transmitters were fitted on some camels for easy detection and observation at any time. These evaluations were used to establish a diet preference or palatability index for observed food plants. Table 1. Palatability index for camels Index Interpretation 1 only eaten when nothing else is available 2 rarely eaten 3 common food plant 4 main food plant at times 5 preferred food plant 6 highly preferred food plant 7 could be killed by camel browsing More information can be obtained from the web site of the Central Australian Camel Industry Association http://www.camelsaust.com.au 2 RESULTS Table 2. -

Austin Land System Unit Landform Soil Vegetation Area (%) 1

Pages 186-237 2/12/08 11:26 AM Page 195 Austin land system Unit Landform Soil Vegetation area (%) 1. 5% Low ridges and rises – low ridges of Shallow red earths and Scattered (10-20% PFC) shrublands outcropping granite, quartz or greenstone shallow duplex soils on or woodlands usually dominated by and low rises, up to 800 m long and granite or greenstone Acacia aneura (mulga) (SIMS). 2-25 m high, and short footslopes with (4b, 5c, 7a, 7b). abundant mantles of cobbles and pebbles. 2. 80% Saline stony plains – gently undulating Shallow duplex soils on Very scattered to scattered (2.5- plains extending up to 3 km, commonly greenstone (7b). 20% PFC) Maireana spp. low with mantles of abundant to very abundant shrublands (SBMS), Maireana quartz or ironstone pebbles. species include M. pyramidata (sago bush), M. glomerifolia (ball- leaf bluebush), M. georgei (George’s bluebush) and M. triptera (three- winged bluebush). 3. 10% Stony plains – gently undulating plains Shallow red earths on Very scattered to scattered (2.5- within or above unit 2; quartz and granite granite (5c). 20% PFC) low shrublands (SGRS). pebble mantles and occasional granite outcrop. 4. <1% Drainage foci – small discrete Red clays of variable depth Moderately close to close (20-50% (10-50 m in diameter) depositional zones, on hardpan or parent rock PFC) acacia woodland or tall occurring sparsely within units 2 and 5. (9a, 9b). shrubland; dominant species are A. aneura and A. tetragonophylla (curara) (GRMU). 5. 5% Drainage lines – very gently inclined Deep red earths (6a). Very scattered (2.5-10% PFC) A linear drainage tracts, mostly unchannelled aneura low woodland or tall but occasionally incised with rills, gutters shrubland (HPMS) or scattered and shallow gullies; variable mantles of Maireana spp. -

Acacia Coolgardiensis Maiden

WATTLE Acacias of Australia Acacia coolgardiensis Maiden Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin Source: Australian Plant Image Index (dig.22402). ANBG © M. Fagg, 2011 Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin Source: Australian Plant Image Index (dig.22403). ANBG © M. Fagg, 2011 Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver.