Conservation of Temporary Wetlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fig. Ap. 2.1. Denton Tending His Fairy Shrimp Collection

Fig. Ap. 2.1. Denton tending his fairy shrimp collection. 176 Appendix 1 Hatching and Rearing Back in the bowels of this book we noted that However, salts may leach from soils to ultimately if one takes dry soil samples from a pool basin, make the water salty, a situation which commonly preferably at its deepest point, one can then "just turns off hatching. Tap water is usually unsatis- add water and stir". In a day or two nauplii ap- factory, either because it has high TDS, or because pear if their cysts are present. O.K., so they won't it contains chlorine or chloramine, disinfectants always appear, but you get the idea. which may inhibit hatching or kill emerging If your desire is to hatch and rear fairy nauplii. shrimps the hi-tech way, you should get some As you have read time and again in Chapter 5, guidance from Brendonck et al. (1990) and temperature is an important environmental cue for Maeda-Martinez et al. (1995c). If you merely coaxing larvae from their dormant state. You can want to see what an anostracan is like, buy some guess what temperatures might need to be ap- Artemia cysts at the local aquarium shop and fol- proximated given the sample's origin. Try incu- low directions on the container. Should you wish bation at about 3-5°C if it came from the moun- to find out what's in your favorite pool, or gather tains or high desert. If from California grass- together sufficient animals for a study of behavior lands, 10° is a good level at which to start. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of Anostracans (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) Inferred from Nuclear 18S Ribosomal DNA (18S Rdna) Sequences

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 25 (2002) 535–544 www.academicpress.com Phylogenetic analysis of anostracans (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) inferred from nuclear 18S ribosomal DNA (18S rDNA) sequences Peter H.H. Weekers,a,* Gopal Murugan,a,1 Jacques R. Vanfleteren,a Denton Belk,b and Henri J. Dumonta a Department of Biology, Ghent University, Ledeganckstraat 35, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium b Biology Department, Our Lady of the Lake University of San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78207, USA Received 20 February 2001; received in revised form 18 June 2002 Abstract The nuclear small subunit ribosomal DNA (18S rDNA) of 27 anostracans (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) belonging to 14 genera and eight out of nine traditionally recognized families has been sequenced and used for phylogenetic analysis. The 18S rDNA phylogeny shows that the anostracans are monophyletic. The taxa under examination form two clades of subordinal level and eight clades of family level. Two families the Polyartemiidae and Linderiellidae are suppressed and merged with the Chirocephalidae, of which together they form a subfamily. In contrast, the Parartemiinae are removed from the Branchipodidae, raised to family level (Parartemiidae) and cluster as a sister group to the Artemiidae in a clade defined here as the Artemiina (new suborder). A number of morphological traits support this new suborder. The Branchipodidae are separated into two families, the Branchipodidae and Ta- nymastigidae (new family). The relationship between Dendrocephalus and Thamnocephalus requires further study and needs the addition of Branchinella sequences to decide whether the Thamnocephalidae are monophyletic. Surprisingly, Polyartemiella hazeni and Polyartemia forcipata (‘‘Family’’ Polyartemiidae), with 17 and 19 thoracic segments and pairs of trunk limb as opposed to all other anostracans with only 11 pairs, do not cluster but are separated by Linderiella santarosae (‘‘Family’’ Linderiellidae), which has 11 pairs of trunk limbs. -

Updated Status of Anostraca in Pakistan

Int. J. Biol. Res., 2(1): 1-7, 2014. UPDATED STATUS OF ANOSTRACA IN PAKISTAN Quddusi B. Kazmi1* and Razia Sultana2 1Marine Reference Collection and Resource Center; University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan 2Food & Marine Resources Research Center, PCSIR Laboratories Complex Karachi; Karachi-75270, Pakistan *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Previously, nine species of the order Anostraca have been reported from Pakistan viz, Branchinella hardingi (Qadri and Baqai, 1956), B. spinosa (H. Milne Edwards, 1840) (now Phallocryptus spinosa), Streptocephalus simplex, 1906, S. dichotomus Baird, 1860, S. maliricus Qadri and Baqai, 1956, S. lahorensis Ghauri and Mahoon, 1980, Branchipus schaefferi Fischer, 1834, Chirocephalus priscus Daday, 1910 and Artemia sp. In the present report these Pakistani species are reviewed. Streptocephalus dichotomus collected from Pasni (Mekran), housed in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, USA (cat no. 213712) is inserted herein and another specimen of Streptocephalus sp., from a new locality, collected from Kalat not yet reported, is illustrated and described in this report, thus extending genus range further Northward. The need for further surveys directed towards getting the knowledge necessary in order to correctly understand and manage temporary pools- the elective habitat of large branchiopods is stressed. KEYWORDS: Anostraca, Brianchiopoda, Pakistan, Present status INTRODUCTION Anostraca is one of the four orders of Crustacea in the Class Branchiopoda. It is the most -

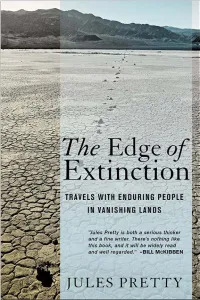

The Edge of Extinction: Travels with Enduring People in Vanishing

THE EDGE OF EXTINCTION Th e Edge of Extinction TRAVELS WITH ENDURING PEOPLE IN VANISHING LANDS M jules pretty Comstock Publishing Associates a division of Cornell University Press Ithaca and London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pretty, Jules N., author. Th e Edge of extinction : travels with enduring people in vanishing lands / Jules Pretty. pages cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8014-5330-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Nature—Eff ect of human beings on—Moral and ethical aspects. 2. Human beings—Eff ect of environment on—Moral and ethical aspects. I. Title. GF80.P73 2014 304.2—dc23 2014017464 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fi bers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu . Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 { iv } For My father, John Pretty (1932–2012), and mother, Susan and Gill, Freya, and Th eo Without my journey And without this spring I would have missed this dawn. -

Uncovering Ultrastructural Defences in Daphnia Magna – an Interdisciplinary Approach to Assess the Predator- Induced Fortification of the Carapace

Uncovering Ultrastructural Defences in Daphnia magna – An Interdisciplinary Approach to Assess the Predator- Induced Fortification of the Carapace Max Rabus1,2*, Thomas Söllradl3, Hauke Clausen-Schaumann3,4, Christian Laforsch2,5 1 Department of Biology II, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany, 2 Department of Animal Ecology I, University of Bayreuth, Germany, 3 Department of Precision, and Micro-Engineering, Engineering Physics, University of Applied Sciences Munich, Germany, 4 Center for NanoScience, Ludwig-Maximilians- University Munich, Germany, 5 Geo-Bio Center, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany Abstract The development of structural defences, such as the fortification of shells or exoskeletons, is a widespread strategy to reduce predator attack efficiency. In unpredictable environments these defences may be more pronounced in the presence of a predator. The cladoceran Daphnia magna (Crustacea: Branchiopoda: Cladocera) has been shown to develop a bulky morphotype as an effective inducible morphological defence against the predatory tadpole shrimp Triops cancriformis (Crustacea: Branchiopoda: Notostraca). Mediated by kairomones, the daphnids express an increased body length, width and an elongated tail spine. Here we examined whether these large scale morphological defences are accompanied by additional ultrastructural defences, i.e. a fortification of the exoskeleton. We employed atomic force microscopy (AFM) based nanoindentation experiments to assess the cuticle hardness along with tapping mode AFM imaging to visualise the surface morphology for predator exposed and non-predator exposed daphnids. We used semi-thin sections of the carapace to measure the cuticle thickness, and finally, we used fluorescence microscopy to analyse the diameter of the pillars connecting the two carapace layers. We found that D. magna indeed expresses ultrastructural defences against Triops predation. -

Anamorphic Development and Extended Parental Care in a 520 Million-Year-Old Stem-Group Euarthropod from China

Fu et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2018) 18:147 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1262-6 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Anamorphic development and extended parental care in a 520 million-year-old stem-group euarthropod from China Dongjing Fu1* , Javier Ortega-Hernández2,3, Allison C Daley4, Xingliang Zhang1 and Degan Shu1 Abstract Background: Extended parental care is a complex reproductive strategy in which progenitors actively look after their offspring up to – or beyond – the first juvenile stage in order to maximize their fitness. Although the euarthropod fossil record has produced several examples of brood-care, the appearance of extended parental care within this phylum remains poorly constrained given the scarcity of developmental data for Palaeozoic stem-group representatives that would link juvenile and adult forms in an ontogenetic sequence. Results: Here, we describe the post-embryonic growth of Fuxianhuia protensa from the early Cambrian Chengjiang Lagerstätte in South China. Our data demonstrate anamorphic post-embryonic development for F. protensa,in which new tergites were sequentially added from a posterior growth zone, the number of tergites varies from eight to 30. The growth of F. protensa is typified by the alternation between segment addition, followed by the depletion of the anteriormost abdominal segment into the thoracic region. The transformation of abdominal into thoracic tergite is demarcated by the development of laterally tergopleurae, and biramous walking legs. The new ontogeny data leads to the recognition of the rare Chengjiang euarthropod Pisinnocaris subconigera as a junior synonym of Fuxianhuia. Comparisons between different species of Fuxianhuia and with other genera within Fuxianhuiida suggest that heterochrony played a prominent role in the morphological diversification of fuxianhuiids. -

Crustacea, Notostraca) from Iran

Journal of Biological Research -Thessaloniki 19 : 75 – 79 , 20 13 J. Biol. Res. -Thessalon. is available online at http://www.jbr.gr Indexed in: Wos (Web of science, IsI thomson), sCOPUs, CAs (Chemical Abstracts service) and dOAj (directory of Open Access journals) — Short CommuniCation — on the occurrence of Lepidurus apus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Crustacea, notostraca) from iran Behroz AtAshBAr 1,2 *, N aser Agh 2, L ynda BeLAdjAL 1 and johan MerteNs 1 1 Department of Biology , Faculty of Science , Ghent University , K.L. Ledeganckstraat 35 , 9000 Gent , Belgium 2 Department of Biology and Aquaculture , Artemia and Aquatic Animals Research Institute , Urmia University , Urmia-57153 , Iran received: 16 November 2011 Accepted after revision: 18 july 2012 the occurrence of Lepidurus apus in Iran is reported for the first time. this species was found in Aigher goli located in the mountains area, east Azerbaijan province (North east, Iran). details on biogeography, ecology and morphology of this species are provided. Key words: Lepidurus apus , Aigher goli, east Azerbaijan, Iran. INtrOdUCtION their world-wide distribution is due to their anti qu - ity, but possibly also to their passive transport: geo - Notostracan records date back to the Carboniferous graphical barriers are more effective for non-passive - and possibly up to the devonian period (Wallossek, ly distributed animals. From an ecological point of 1993, 1995; Kelber, 1998). In fact, there are Upper view, notostracans, like most branchiopods, are re - triassic Triops fossils from germany -

Lepidurus Arcticus (Crustacea : Notostraca); an Unexpected Prey of Arctic Charr (Salvelinus Alpinus) in a High Arctic River

BOREAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH 23: 149–157 © 2018 ISSN 1797-2469 (online) Helsinki 20 April 2018 Lepidurus arcticus (Crustacea : Notostraca); an unexpected prey of Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) in a High Arctic river Reidar Borgstrøm1)*, Morten Aas1)2), Hanne Hegseth1)2), J. Brian Dempson3) and Martin-Arne Svenning2) 1) Faculty of Environmental Sciences and Natural Resource Management, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, P.O. Box 5003, NO-1432 Ås, Norway (*corresponding author’s e-mail: reidar.borgstrom@ nmbu.no) 2) Norwegian Institute of Nature Research, Arctic Ecology Department, Fram Center, P.O. Box 6606 Langnes, NO-9296 Tromsø, Norway 3) Fisheries & Oceans Canada, Science Branch, 80 East White Hills Road, P.O. Box 5667, St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1, Canada Received 20 Dec. 2017, final version received 16 Mar. 2018, accepted 12 Apr. 2018 Borgstrøm R., Aas M., Hegseth H., Dempson J.B. & Svenning M.-A. 2018: Lepidurus arcticus (Crusta- cea : Notostraca); an unexpected prey of Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) in a High Arctic river. Boreal Env. Res. 23: 149–157. The phyllopod Lepidurus arcticus, commonly called the arctic tadpole shrimp, is an important food item of both Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus and brown trout Salmo trutta in lakes in Iceland and Scandinavia, especially at low fish densities. In the High Arctic, the tadpole shrimp is abundant in fishless localities, but absent or rare in most lakes where fish are present. We studied the diet of Arctic charr in the Straumsjøen watercourse on Spitsbergen, the main island of Svalbard. The outlet river is dry nine months of the year, and all Arctic charr present during summer have descended from the lake. -

Crustacea: Notostraca) from Serbia

Arthropoda Selecta 28(1): 65–72 © ARTHROPODA SELECTA, 2019 Developmental and other body abnormalities in the genus Lepidurus Leach, 1819 (Crustacea: Notostraca) from Serbia Îòêëîíåíèÿ â ðàçâèòèè è äðóãèå íàðóøåíèÿ ñòðîåíèÿ òåëà â ðîäå Lepidurus Leach, 1819 (Crustacea: Notostraca) â Ñåðáèè Ivana Šaganović, Slobodan Makarov, Luka Lučić, Sofija Pavković- Lučić, Vladimir Tomić, Dragana Miličić Èâàíà Øàãàíîâèћ, Ñëîáîäàí Ìàêàðîâ, Ëóêà Ëó÷èћ, Ñîôè¼à Ïàâêîâèћ-Ëó÷èћ, Âëàäèìèð Òîìèћ, Äðàãàíà Ìèëè÷èћ University of Belgrade, Faculty of Biology, Institute of Zoology, Studentski Trg 16, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia. Университет Белграда, Биологический факультет, Институт зоологии, Белград, Сербия. KEY WORDS: morphological abnormalities, Lepidurus, Serbia. КЛЮЧЕВЫЕ СЛОВА: морфологические отклонения, Lepidurus, Сербия. ABSTRACT. The occurrence of morphological ab- шние изменения в строении тела у крупных рако- normalities and the emergence of body defects are образных-бранхиопод рода Lepidurus Leach, 1819 well-known phenomena in crustaceans and other groups (Notostraca), собранных в Сербии, и обсудить их of arthropods. They usually originate from genetic fac- возможную этиологию. Большинство изменений tors and are attributable to aberrations during the moult- отмечены у карапакса и конечностей, а затем у ing process, but they can also be of exogenous origin. брюшного отдела, тельсона с хвостовой долей и у The aims of this study were to present the external церкоподов. Что касается потенциальных причин, body changes that occurred in large branchiopod crus- наблюдаемые изменения могут вызываться как ге- taceans of the genus Lepidurus Leach, 1819 (Notostra- нетическими, так и негенетическими факторами ca) sampled in Serbia and discuss their possible etiolo- типа пресс хищников и возможные нарушения при- gy. The majority of variations were identified on the родной среды. -

Rock, Cherry Creek, Nannie Creek

Rock, Cherry and Narmie r-teks 3rhw t ;MeA o;- Watershed Analysis A 13.2: R 6 2/2x Winema National Forest - / TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. DESCRIPTION OF THE WATERSHED AREA 1 A. Location and Land Management 1 B. Geology 7 C. Climate 9 D. Soils 9 E. Hydrology 10 F. Potential Vegetation 10 III. BENEFICIAL USES AND VALUES 12 A. Biodiversity 12 B. Wilderness/Research Natural Area 12 C. Recreation 12 D. Cultural Resources 13 E. Timber and Roads 14 F. Agriculture and Water Source 14 G. Mineral Resources 15 H. Aesthetic/Scenic Values 15 IV. ISSUES TO BE EVALUATED 16 V. ANALYSIS OF ISSUES 17 A. Forest Health Decline 17 B. Wildlife and Plant Habitat Alteration 22 C. Fish Stocking in Subalpine Lakes 29 D. Impact to Native Fish Populations 31 E. Fish Habitat Degradation 36 F. Channel Condition Alteration 41 G. Hydrograph Change 45 H. Increased Sediment Loading 56 VI. MANAGEMENT RECOMMENDATIONS AND RESTORATION OPPORTUNITIES 63 A. Upland Forests 63 B. Low Elevation Wetlands 63 C. Fish/Aquatic Habitats 64 D. Roads and Channel Morphology 64 E. Trails 67 F. Riparian Reserves 67 G. Geomorphological Reserves 69 H. Soils 69 VII. REFERENCES 70 VIII. APPENDICES A. List of People Consulted 74 B. Wildlife Species 75 C. Plant and Fungi Species 80 D. Source of Vegetation Data 89 |&j0hERN OflEGOX~@NUND~IVEAQ UORARY WATERSHED ANALYSIS REPORT FOR THE ROCK, CHERRY. AND NANNIE CREEK WATERSHED AREA I. INTRODUCTION This report documents an analysis of the Rock, Cherry, and Nannie Watershed Area. The purpose of the analysis is to develop a scientifically-based understanding of the processes and interactions occurring within the watershed area and the effects of management practices. -

Lost Floodplain Wetland Environments and Efforts to Restore Connectivity, Habitat, and Water Quality Settings on the Great Barrier Reef

fmars-06-00071 February 25, 2019 Time: 15:47 # 1 POLICY AND PRACTICE REVIEWS published: 26 February 2019 doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00071 Lost Floodplain Wetland Environments and Efforts to Restore Connectivity, Habitat, and Water Quality Settings on the Great Barrier Reef Nathan J. Waltham1,2*, Damien Burrows1, Carla Wegscheidl3, Christina Buelow1,2, Mike Ronan4, Niall Connolly3, Paul Groves5, Donna Marie-Audas5, Colin Creighton1 and Marcus Sheaves1,2 1 Centre for Tropical Water and Aquatic Ecosystem Research, College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia, 2 Science for Integrated Coastal Ecosystem Management, School of Marine Biology and Aquaculture, College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia, 3 Rural Economic Development, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Queensland Government, Townsville, QLD, Australia, 4 Department of Environment and Science, Queensland Government, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 5 Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Australian Government, Townsville, QLD, Australia Edited by: Mario Barletta, Departamento de Oceanografia da Managers are moving toward implementing large-scale coastal ecosystem restoration Universidade Federal de Pernambuco projects, however, many fail to achieve desired outcomes. Among the key reasons for (UFPE), Brazil this is the lack of integration with a whole-of-catchment approach, the scale of the Reviewed by: A. Rita Carrasco, project (temporal, spatial), the requirement for on-going costs for maintenance, the Universidade do Algarve, Portugal lack of clear objectives, a focus on threats rather than services/values, funding cycles, Jacob L. Johansen, New York University Abu Dhabi, engagement or change in stakeholders, and prioritization of project sites. Here we United Arab Emirates critically assess the outcomes of activities in three coastal wetland complexes positioned *Correspondence: along the catchments of the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) lagoon, Australia, that have Nathan J. -

Crustacea: Branchiopoda: Anostraca

N. 97 Oct. 12,2002 ~ V) l n Biology and Geology ~ ~ V) Z ~ ~ 0 ~ Minnesota and Wisconsin Fairy Shrimps (Crustacea: U Branchiopoda: Anostraca) ~ •.......• including information on .......l other species of the Midwest o::l :::J By Joan Jass and Barbara Klausmeier Zoology Section ~ ~ Milwaukee Public Museum p.., 800 West Wells Street ~ ~ Milwaukee, WI 53233 Illustrated by Dale A. Chelberg ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ -< Z ~ .......l - 0 Milwaukee Public ~ U MUSEUM Milwaukee Public Museum Contributions in Biology and Geology Paul Mayer, Editor This publication is priced at $6.00 and may be obtained by writing to the Museum Shop, Milwaukee Public Museum, 800 West Wells Street, Milwaukee, WI 53233. Orders must include $3.00 for shipping and handling ($4.00 for foreign destinations) and must be accompanied by money order or check drawn on U.S. bank. Money orders or checks should be made payable to the Milwaukee Public Museum, Inc. Wisconsin residents please add 5% sales tax. ISBN 0-89326-210-2 ©2002 Milwaukee Public Museum, Inc. Sponsored by Milwaukee County Abstract Fieldwork in Minnesota and Wisconsin is summarized, providing new distribution information for the fairy shrimps in these states. Each species found in the field surveys is illustrated in a Picture Key. Maps present Minnesota and Wisconsin locality records from specimens in the collections of the Milwaukee Public Museum (MPM) and the Science Museum of Minnesota (SMM). Distribution and natural history information for anostra- cans from other states in the Midwestern region are also included. By far the most common fairy shrimp in Minnesota and Wisconsin is Eubranchipus bundyi. Hatching phenomena and records of predators are discussed.