Opening Pages.Rtf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soul Top 1000

UUR 1: 14 april 9 uur JAAP 1000 Isley Brothers It’s Your Thing 999 Jacksons Enjoy Yourself 998 Eric Benet & Faith Evans Georgy Porgy 997 Delfonics Ready Or Not Here I Come 996 Janet Jackson What Have Your Done For Me Lately 995 Michelle David & The Gospel Sessions Love 994 Temptations Ain’t Too Proud To Beg 993 Alain Clark Blow Me Away 992 Patti Labelle & Michael McDonald On My Own 991 King Floyd Groove Me 990 Bill Withers Soul Shadows UUR 2: 14 april 10 uur NON-STOP 989 Michael Kiwanuka & Tom Misch Money 988 Gloria Jones Tainted Love 987 Toni Braxton He Wasn’t Man Enough 986 John Legend & The Roots Our Generation 985 Sister Sledge All American Girls 984 Jamiroquai Alright 983 Carl Carlton She’s A Bad Mama Jama 982 Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings Better Things 981 Anita Baker You’re My Everything 980 Jon Batiste I Need You 979 Kool & The Gang Let’s Go Dancing 978 Lizz Wright My Heart 977 Bran van 3000 Astounded 976 Johnnie Taylor What About My Love UUR 3: 14 april 11 uur NON-STOP 975 Des’ree You Gotta Be 974 Craig David Fill Me In 973 Linda Lyndell What A Man 972 Giovanca How Does It Feel 971 Alexander O’ Neal Criticize 970 Marcus King Band Homesick 969 Joss Stone Don’t Cha Wanna Ride 1 968 Candi Staton He Called Me Baby 967 Jamiroquai Seven Days In Sunny June 966 D’Angelo Sugar Daddy 965 Bill Withers In The Name Of Love 964 Michael Kiwanuka One More Night 963 India Arie Can I Walk With You UUR 4: 14 april 12 uur NON-STOP 962 Anthony Hamilton Woo 961 Etta James Tell Mama 960 Erykah Badu Apple Tree 959 Stevie Wonder My Cherie Amour 958 DJ Shadow This Time (I’m Gonna Try It My Way) 957 Alicia Keys A Woman’s Worth 956 Billy Ocean Nights (Feel Like Gettin' Down) 955 Aretha Franklin One Step Ahead 954 Will Smith Men In Black 953 Ray Charles Hallelujah I Love Her So 952 John Legend This Time 951 Blu Cantrell Hit' m Up Style 950 Johnny Pate Shaft In Africa 949 Mary J. -

1 Hey Jude the Beatles 1968 2 Stairway to Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 3 Stayin' Alive Bee Gees 1978 4 YMCA Village People 1979 5

1 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 2 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 3 Stayin' Alive Bee Gees 1978 4 YMCA Village People 1979 5 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 6 Da Ya Think I'm Sexy? Rod Stewart 1979 7 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 8 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 9 Tragedy Bee Gees 1979 10 Le Freak Chic 1978 11 Macho Man Village People 1978 12 I Will Survive Gloria Gaynor 1979 13 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 14 Night Fever Bee Gees 1978 15 Fire Pointer Sisters 1979 16 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 17 Shake Your Groove Thing Peaches & Herb 1979 18 Hound Dog Elvis Presley 1956 19 Heartbreak Hotel Elvis Presley 1956 20 The Twist Chubby Checker 1960 21 Johnny B. Goode Chuck Berry 1958 22 Too Much Heaven Bee Gees 1979 23 Last Dance Donna Summer 1978 24 American Pie Don McLean 1972 25 Heaven Knows Donna Summer & Brooklyn Dreams 1979 26 Mack The Knife Bobby Darin 1959 27 Peggy Sue Buddy Holly 1957 28 Grease Frankie Valli 1978 29 Love Me Tender Elvis Presley 1956 30 Soul Man Blues Brothers 1979 31 You Really Got Me The Kinks 1964 32 Hot Blooded Foreigner 1978 33 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 34 Layla Derek & The Dominos 1972 35 September Earth, Wind & Fire 1979 36 Don't Be Cruel Elvis Presley 1956 37 Blueberry Hill Fats Domino 1956 38 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 39 Copacabana (At The Copa) Barry Manilow 1978 40 Shadow Dancing Andy Gibb 1978 41 Evergreen (Love Theme From "A Star Is Born") Barbra Streisand 1977 42 Miss You Rolling Stones 1978 43 Mandy Barry Manilow 1975 -

Das SWR1 Hitparädle

Meine Nummer 1: Film- und Serienhits Das SWR1 Hitparädle Platz Titel Interpret 1 Man with the harmonica (Spiel mir das Lied vomMorricone, Tod) Ennio 2 Skyfall Adele 3 Das Boot Doldinger, Klaus 4 Main theme (Star Wars) Williams, John 5 I've had the time of my life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes 6 Who wants to live forever? Queen 7 My heart will go on Dion, Céline 8 Goldfinger Bassey, Shirley 9 Circle of life John, Elton 10 Eye of the tiger Survivor 11 Bohemian Rhapsody Queen 12 He's a pirate Orchester 13 Unknown stuntman Majors, Lee 14 Axel F. Faltermeyer, Harold 15 The Imperial March (Darth Vader's Theme Star Williams,Wars) John 16 Always look on the bright side of life Monty Python 17 Streets of Philadelphia Springsteen, Bruce 18 Shallow Lady Gaga & Bradley Cooper 19 Heroes Bowie, David 20 Live and let die McCartney, Paul & Wings 21 James Bond Theme Barry, John & Orchestra 22 Born to be wild Steppenwolf 23 Everybody needs somebody to love Blues Brothers 24 Golden Eye Turner, Tina 25 I don't want to miss a thing Aerosmith 26 I will always love you Houston, Whitney 27 Aquarius/ Let the sunshine in Fifth Dimension 28 I see fire Sheeran, Ed 29 I will follow him Goldberg, Whoopi 30 The pink panther theme Henry Mancini & His Orchestra 31 The sound of silence Simon & Garfunkel 32 Oh pretty woman Orbison, Roy 33 Flashdance ... what a feeling Cara, Irene 34 The end Doors 35 Mrs. Robinson Simon & Garfunkel 36 Die Biene Maja Gott, Karel 37 Can you feel the love tonight John, Elton 38 Ain't no mountain high enough Gaye, Marvin & Tammi Terrell 39 -

LCSH Section J

J (Computer program language) J. I. Case tractors Thurmond Dam (S.C.) BT Object-oriented programming languages USE Case tractors BT Dams—South Carolina J (Locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) J.J. Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) J. Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) BT Locomotives USE Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) UF Clark Hill Lake (Ga. and S.C.) [Former J & R Landfill (Ill.) J.J. "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) heading] UF J and R Landfill (Ill.) UF "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clark Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) J&R Landfill (Ill.) Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clarks Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) BT Sanitary landfills—Illinois BT Public buildings—Texas Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) J. & W. Seligman and Company Building (New York, J. James Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) BT Lakes—Georgia USE Banca Commerciale Italiana Building (New UF Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Lakes—South Carolina York, N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) Reservoirs—Georgia J 29 (Jet fighter plane) BT Public buildings—Nebraska Reservoirs—South Carolina USE Saab 29 (Jet fighter plane) J. Kenneth Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) J.T. Berry Site (Mass.) J.A. Ranch (Tex.) UF Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) UF Berry Site (Mass.) BT Ranches—Texas BT Post office buildings—Virginia BT Massachusetts—Antiquities J. Alfred Prufrock (Fictitious character) J.L. Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, N.C.) J.T. Nickel Family Nature and Wildlife Preserve (Okla.) USE Prufrock, J. Alfred (Fictitious character) UF Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, UF J.T. -

Great Movie Soundtracks, Part 2

Great movie soundtracks brought to you by HOOPLA! With HOOPLA, you can stream movies, television, e-books, audiobooks and comics – and also music. They carry over 7000 soundtracks, so I narrowed it down to my twenty favorites. Here’s part two of my favorites. La La Land (2016) Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling star Mia, an aspiring actress/barista, and Sebastian, a struggling jazz musician, who fall in love in backdrop of Los Angeles; an homage to the old musicals with a modern twist. The Oscar winning soundtrack includes original, catchy tunes, my favorite being the opening number “Another Day of Sun” – a dance sequence filmed on a real LA Freeway. The Mambo Kings (1992) Armand Assante and Antonio Banderas star as the musician brothers Cesar and Nestor who leave Cuba for America in the 1950’s, hoping to hit the top of the Latin music scene. Soundtrack features many big names from the world of latin jazz and salsa music, including songs by Arturo Sandoval, Celia Cruz, Tito Puente, and Mambo All-Stars. Mamma Mia! (2008) A bride-to-be tries to find her real father told using hit songs by the popular 1970’s group ABBA. If you need an ABBA fix, here it is. National Lampoon's Animal House (1978) John Belushi stars in one of the most irreverent, politically incorrect comedies of all time - follows a group of rowdy fraternity brothers at the fictional Faber College in 1962 and all their shenanigans. Soundtrack includes early sixties classics by Sam Cooke, Lloyd Williams, Paul & Paula, and Stephen Bishop. -

Where Was the Outrage? the Lack of Public Concern for The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by TopSCHOLAR Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 8-2014 Where Was the Outrage? The Lack of Public Concern for the Increasing Sensationalism in Marvel Comics in a Conservative Era 1978-1993 Robert Joshua Howard Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Howard, Robert Joshua, "Where Was the Outrage? The Lack of Public Concern for the Increasing Sensationalism in Marvel Comics in a Conservative Era 1978-1993" (2014). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1406. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1406 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHERE WAS THE OUTRAGE? THE LACK OF PUBLIC CONCERN FOR THE INCREASING SENSATIONALISM IN MARVEL COMICS IN A CONSERVATIVE ERA 1978-1993 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Robert Joshua Howard August 2014 I dedicate this thesis to my wife, Marissa Lynn Howard, who has always been extremely supportive of my pursuits. A wife who chooses to spend our honeymoon fund on a trip to Wyoming, to sit in a stuffy library reading fan mail, all while entertaining two dogs is special indeed. -

BOONE-DISSERTATION.Pdf

Copyright by Christine Emily Boone 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Christine Emily Boone Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics Committee: James Buhler, Supervisor Byron Almén Eric Drott Andrew Dell‘Antonio John Weinstock Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics by Christine Emily Boone, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Acknowledgements I want to first acknowledge those people who had a direct influence on the creation of this document. My brother, Philip, introduced me mashups a few years ago, and spawned my interest in the subject. Dr. Eric Drott taught a seminar on analyzing popular music where I was first able to research and write about mashups. And of course, my advisor, Dr. Jim Buhler has given me immeasurable help and guidance as I worked to complete both my degree and my dissertation. Thank you all so much for your help with this project. Although I am the only author of this dissertation, it truly could not have been completed without the help of many more people. First I would like to thank all of my professors, colleagues, and students at the University of Texas for making my time here so productive. I feel incredibly prepared to enter the field as an educator and a scholar thanks to all of you. I also want to thank all of my friends here in Austin and in other cities. -

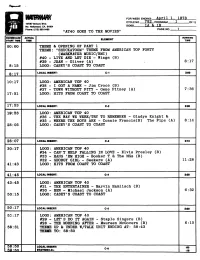

IWJIIARK for WEEK ENDING: A:G;R1l L

~· IWJIIARK FOR WEEK ENDING: A:g;r1l l. 1e:za CYCLE NO. 782 PROGRAM '1 OF13 10700 Ventura Blvd. No. Hollywood, CA. 91604 SIDES lA & lB ] Phone: (213) 980-9490 "AT40 GOES TO THE MOVIES" PAGE NO. SCHeDULED ACTUAL RUNNING ELEMENT STAMTI- ,.... TIME 00:00 THEME & OPENING OF PART 1 THEME: "SHUCKATOOid" THEME FROM AMERICAN TOP FORTY (MARKWATER MUSIC/BMI) #40- LIVE AND LET DIE·- Wings (B) #39 - JEAN - Oliver (A) 8:17 8:15 LOGO: CASEY'S COAST TO COAST 8_.17 LOCAL INSERT: C-1 2:00 10:17• LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #38 - I GOT A NAME - Jim Croce (B) #37 - TOWN WITHOUT PITY - Gene Pitney (A) 7:36 17:51 LOGO: HITS FROM COAST TO COAST 17:53 LOCAL INSERT: C-2 2:00 19:53 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #36 - THE WAY WE WERE/TRY TO REMEMBER - Gladys Knight & #35 - WHERE THE BOYS ARE - Connie Francis(B) The Pips (A) 8:14 28:05 LOGO: CASEY'S COAST TO COAST 28:07 LOCAL INSERT: C-3 2:10 30:17 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #34 - CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE - Elvis Presley (B) #33 - HANG 'EM HIGH - Booker T & The MGs (B) #32 - GEORGY GIRL - Seekers (A) 11:28 41:43 LOGO: HITS FROM COAST TO COAST 41:45 LOCAL INSERT: C-4 2:00 43:45 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #31 - THE ENTERTAINER - Marvin Hamlisch (B) #30 - BEN - Michael Jackson (A) 6:32 50:15 LOGO: CASEY'S COAST TO COAST 50:17 LOCAL INSERT: C-5 2:00 5S:l7 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #29- LET'S DO IT AGAIN- Staple Singers (B) #28 - THE MORNING AFTER - Maureen McGovern (B) 6:15 58:31 THEME UP & UNDER W/TALK UNIT ENDING AT: 58:43 1'BBD TO: 58:50 I LOCAL·~~~ 1: c-e ;:~~~ :10 M1IMI49( FOR WEEK ENDING: AQril 1 1 1978 CYCLE NO. -

HAYES by ROB BOWMAN

i S f ? PERFORMERS HAYES By ROB BOWMAN IN THE PAST FIFTY YEARS, THERE HAVE BEEN A HAND- Hayes’s story is one of epic proportions. Begin ful of seminal, innovative albums that truly changed ning in 1969, with the release of Hot Buttered Soul, the course of popular-music history. LPs such as he became the biggest artist Stax Records ever pro Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, James Brown’s Live at the duced and one of the most important artists in the Apollo, the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club history of rhythm & blues. In the first few years of Band and the Sex Pistols’ Never Mind the Bollocks the 1970s, he single-handedly redefined the sonic opened new doors, created new possibilities and possibilities for black music, in the process opening suggested new directions to other musicians, record up the album market as a commercially viable me company personnel and fans alike. Each of these al dium for black artists. Earlier, Hayes, alongside bums, in its own way, defined a moment in time, cap partner David Porter, had helped shape the sound tured the Zeitgeist of an era and helped create a mu of soul music in the 1960s with such definitive com sical subgenre in the process. To have created one positions as “Hold On! I’m a Cornin’,” “Soul Man,” such album over the course of a career “When Something Is Wrong With My Isaac Hayes: (Opposite) is a heady accomplishment. To have Baby,” “B-A-B-Y,” “I T hank You” and In 1972, in Shaft mode, and “Wrap It Up.” The fact that one artist done it twice, as Isaac Hayes did with (above) as Black Moses, Hot Buttered Soul and Shaft, puts one in the title of one of three could be responsible for such disparate extremely rarefied company indeed. -

PG-13 Song List 2 Pages

Ramapo Runway “It’s A Wrap” Movie Song Guide MOVIE SONG ARTIST 21 Jump Street Party Rock Anthem LMFAO 8 Mile Lose Yourself Eminem Beverly Hills Cop Axel F Harold Faltermeyer Garden State Don’t Panic (slow) Coldplay Garden State New Slang (slow) The Shins Slumdog Millionaire Jai Ho AR Rahman Almost Famous Reelin’ in the Years Steeley Dan Trainspotting Perfect Day (slow) Lou Reed The Hangover Who Let the Dogs Out Baha Men The Hangover Yeah Usher The Hangover Right Round Flo Rida Goodfellas Layla Eric Clapton Space Jam I Believe I Can Fly (slow) R. Kelly American Reunion Wannabe Spice Girls American Reunion Tub Thumping Chumbawumba American Reunion Sexy and I Know It LMFAO Toy Story You Got a Friend In Me (slow) Randy Newman James Bond (any) James Bond Theme (slow) Monty Norman Shaft Theme from Shaft Isaac Hayes Pink Panther Theme from Pink Panther Henry Mancini Wayne’s World Theme from Wayne’s World Wayne and Garth La Bamba La Bamba Richie Valens Grease You’re the One That I want Travolta/Newton-John Grease Summer Nights Cast Grease We Go Together Cast Men In Black Big Willie Style Will Smith Men In Black 3 Back in Time Pitbull Jackass 3-D Boom Boom Pow Black Eyed Peas The Help Sherry Frankie Valli & the 4 Seasons Pulp Fiction Jungle Boogie Kool and the Gang Blues Brothers Twist It/Shake your tail The Blues Brothers Blues Brothers Soul Man The Blues Brothers Blues Brothers Everybody Needs Somebody The Blues Brothers Ferris Bueller’s Day Off Twist and Shout Beatles Iron Man Back in Black AC/DC Shrek All-Star Smash Mouth Shrek 2 Accidentally in Love Counting Crows Shrek 2 Funkytown Lipps, Inc. -

The Top 200 Greatest Funk Songs

The top 200 greatest funk songs 1. Get Up (I Feel Like Being a Sex Machine) Part I - James Brown 2. Papa's Got a Brand New Bag - James Brown & The Famous Flames 3. Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice Elf Agin) - Sly & The Family Stone 4. Tear the Roof Off the Sucker/Give Up the Funk - Parliament 5. Theme from "Shaft" - Isaac Hayes 6. Superfly - Curtis Mayfield 7. Superstition - Stevie Wonder 8. Cissy Strut - The Meters 9. One Nation Under a Groove - Funkadelic 10. Think (About It) - Lyn Collins (The Female Preacher) 11. Papa Was a Rollin' Stone - The Temptations 12. War - Edwin Starr 13. I'll Take You There - The Staple Singers 14. More Bounce to the Ounce Part I - Zapp & Roger 15. It's Your Thing - The Isley Brothers 16. Chameleon - Herbie Hancock 17. Mr. Big Stuff - Jean Knight 18. When Doves Cry - Prince 19. Tell Me Something Good - Rufus (with vocals by Chaka Khan) 20. Family Affair - Sly & The Family Stone 21. Cold Sweat - James Brown & The Famous Flames 22. Out of Sight - James Brown & The Famous Flames 23. Backstabbers - The O'Jays 24. Fire - The Ohio Players 25. Rock Creek Park - The Blackbyrds 26. Give It to Me Baby - Rick James 27. Brick House - The Commodores 28. Jungle Boogie - Kool & The Gang 29. Shining Star - Earth, Wind, & Fire 30. Got To Give It Up Part I - Marvin Gaye 31. Keep on Truckin' Part I - Eddie Kendricks 32. Dazz - Brick 33. Pick Up the Pieces - Average White Band 34. Hollywood Singing - Kool & The Gang 35. Do It ('Til You're Satisfied) - B.T. -

1 Marvin Gaye What's Going on 2 Otis Redding

1 Marvin Gaye What's going on 2 Otis Redding (Sittin' on) The dock of the bay 3 Amy Winehouse Back to black 4 Marvin Gaye Let's get it on 5 Kyteman Sorry 6 Bill Withers Ain't no sunshine 7 Stevie Wonder Superstition 8 John Legend All of me 9 Aretha Franklin Respect 10 Miles Davis So what 11 Sam Cooke A change is gonna come 12 Curtis Mayfield Move on up 13 Al Green Let's stay together 14 James Brown It's a man's man's man's world 15 Michael Jackson Billie Jean 16 Gregory Porter Be good (lion's song) 17 Temptations Papa was a rollin' stone 18 Beyonce ft. Jay-Z Crazy in love 19 Dave Brubeck Take five 20 Earth Wind & Fire September 21 Erykah Badu Tyrone (live) 22 Gregory Porter 1960 what 23 Stevie Wonder As 24 Daft Punk ft. Pharrell & Nile RodgersGet lucky 25 Gladys Knight & The Pips Midnight train to Georgia 26 James Brown Sex machine 27 Michael Kiwanuka Home again 28 Michael Jackson Don't stop 'till you get enough 29 B.B. King The thrill is gone 30 Luther Vandross Never too much 31 Stevie Wonder Sir Duke 32 Michael Jackson Off the wall 33 Donny Hathaway A song for you 34 Bobby Womack Across 110th street 35 Earth Wind & Fire Fantasy 36 Bill Withers Grandma's hands 37 Roots ft. Cody Chesnutt The seed (2.0) 38 Billy Paul Me and mrs Jones 39 Marvin Gaye I heard it through the grapevine 40 Etta James At last 41 Chaka Khan I'm every woman 42 Bill Withers Lovely day 43 Giovanca How does it feel 44 Isaac Hayes Theme from Shaft 45 Alicia Keys Empire state of mind (part 2) 46 Chic Le freak 47 Dusty Springfield Son of a preacher man 48 Pharrell Happy