Certificate Acknowledgement Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

MUMBAI an EMERGING HUB for NEW BUSINESSES & SUPERIOR LIVING 2 Raigad: Mumbai - 3.0

MUMBAI AN EMERGING HUB FOR NEW BUSINESSES & SUPERIOR LIVING 2 Raigad: Mumbai - 3.0 FOREWORD Anuj Puri ANAROCK Group Group Chairman With the island city of Mumbai, Navi Mumbai contribution of the district to Maharashtra. Raigad and Thane reaching saturation due to scarcity of is preparing itself to contribute significantly land parcels for future development, Raigad is towards Maharashtra’s aim of contributing US$ expected to emerge as a new destination offering 1 trillion to overall Indian economy by 2025. The a fine balance between work and pleasure. district which is currently dominated by blue- Formerly known as Kolaba, Raigad is today one collared employees is expected to see a reverse of the most prominent economic districts of the in trend with rising dominance of white-collared state of Maharashtra. The district spans across jobs in the mid-term. 7,152 sq. km. area having a total population of 26.4 Lakh, as per Census 2011, and a population Rapid industrialization and urbanization in density of 328 inhabitants/sq. km. The region Raigad are being further augmented by massive has witnessed a sharp decadal growth of 19.4% infrastructure investments from the government. in its overall population between 2001 to 2011. This is also attributing significantly to the overall Today, the district boasts of offering its residents residential and commercial growth in the region, a perfect blend of leisure, business and housing thereby boosting overall real estate growth and facilities. uplifting and improving the quality of living for its residents. Over the past few years, Raigad has become one of the most prominent districts contributing The report titled ‘Raigad: Mumbai 3.0- An significantly to Maharashtra’s GDP. -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : MUMBAI Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 16.01.001 SAKHARAM SHETH VIDYALAYA, KALYAN,THANE 185 185 22 57 52 29 160 86.48 27210508002 16.01.002 VIDYANIKETAN,PAL PYUJO MANPADA, DOMBIVLI-E, THANE 226 226 198 28 0 0 226 100.00 27210507603 16.01.003 ST.TERESA CONVENT 175 175 132 41 2 0 175 100.00 27210507403 H.SCHOOL,KOLEGAON,DOMBIVLI,THANE 16.01.004 VIVIDLAXI VIDYA, GOLAVALI, 46 46 2 7 13 11 33 71.73 27210508504 DOMBIVLI-E,KALYAN,THANE 16.01.005 SHANKESHWAR MADHYAMIK VID.DOMBIVALI,KALYAN, THANE 33 33 11 11 11 0 33 100.00 27210507115 16.01.006 RAYATE VIBHAG HIGH SCHOOL, RAYATE, KALYAN, THANE 151 151 37 60 36 10 143 94.70 27210501802 16.01.007 SHRI SAI KRUPA LATE.M.S.PISAL VID.JAMBHUL,KULGAON 30 30 12 9 2 6 29 96.66 27210504702 16.01.008 MARALESHWAR VIDYALAYA, MHARAL, KALYAN, DIST.THANE 152 152 56 48 39 4 147 96.71 27210506307 16.01.009 JAGRUTI VIDYALAYA, DAHAGOAN VAVHOLI,KALYAN,THANE 68 68 20 26 20 1 67 98.52 27210500502 16.01.010 MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KUNDE MAMNOLI, KALYAN, THANE 53 53 14 29 9 1 53 100.00 27210505802 16.01.011 SMT.G.L.BELKADE MADHYA.VIDYALAYA,KHADAVALI,THANE 37 36 2 9 13 5 29 80.55 27210503705 16.01.012 GANGA GORJESHWER VIDYA MANDIR, FALEGAON, KALYAN 45 45 12 14 16 3 45 100.00 27210503403 16.01.013 KAKADPADA VIBHAG VIDYALAYA, VEHALE, KALYAN, THANE 50 50 17 13 -

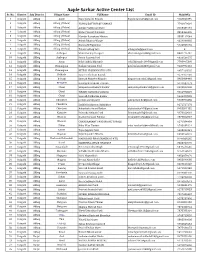

Aaple Sarkar Active Center List Sr

Aaple Sarkar Active Center List Sr. No. District Sub District Village Name VLEName Email ID MobileNo 1 Raigarh Alibag Akshi Sagar Jaywant Kawale [email protected] 9168823459 2 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) VISHAL DATTATREY GHARAT 7741079016 3 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Ashish Prabhakar Mane 8108389191 4 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Kishor Vasant Nalavade 8390444409 5 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Mandar Ramakant Mhatre 8888117044 6 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Ashok Dharma Warge 9226366635 7 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Karuna M Nigavekar 9922808182 8 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Tahasil Alibag Setu [email protected] 0 9 Raigarh Alibag Ambepur Shama Sanjay Dongare [email protected] 8087776107 10 Raigarh Alibag Ambepur Pranit Ramesh Patil 9823531575 11 Raigarh Alibag Awas Rohit Ashok Bhivande [email protected] 7798997398 12 Raigarh Alibag Bamangaon Rashmi Gajanan Patil [email protected] 9146992181 13 Raigarh Alibag Bamangaon NITESH VISHWANATH PATIL 9657260535 14 Raigarh Alibag Belkade Sanjeev Shrikant Kantak 9579327202 15 Raigarh Alibag Beloshi Santosh Namdev Nirgude [email protected] 8983604448 16 Raigarh Alibag BELOSHI KAILAS BALARAM ZAVARE 9272637673 17 Raigarh Alibag Chaul Sampada Sudhakar Pilankar [email protected] 9921552368 18 Raigarh Alibag Chaul VINANTI ANKUSH GHARAT 9011993519 19 Raigarh Alibag Chaul Santosh Nathuram Kaskar 9226375555 20 Raigarh Alibag Chendhre pritam umesh patil [email protected] 9665896465 21 Raigarh Alibag Chendhre Sudhir Krishnarao Babhulkar -

District Census Handbook, Yeotmal, Part a & B

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK YEOTMAL Part A-Town & Village Directory Part B-Primary Census Abstract Compiled by THE MAHARASHTRA CENSUS OFFICE BOMBAY Printed fn lodia by tbe Maoager. Nayan Printing Press. Gandhi R.oad. AJunocIabacS-J. and Published by the Director. Goveromont PriDtins and StatiODetJ Mabaraahtra Stat.. Bomba),-4 1973 {Prioe-Rs. Elabt ) ; ~ ...'" i t £ g ;;t S t- ,...o '-' Iii: a:::: « <C..... :I: ~ -e. V) « ~ __, <C« \ cc :I: « ~ :E: I: 0..... - 0 <> ·0 - o Q. :I: .." W o « ", a: a.. -« a:: Q " /( ::I: .... a l-- ' ~ ~: '" ,/. ~ ~ z • Ell < .. o z -._ ...... "".", o CENSUS OF INDIA 1m ---_ CeDtra' G.ftftmlent Publicatl_ Census Report, Series ll-Maharashtra~ is published in the following Parts I·A and JI •. -Geoanl Re,ort I-C •• Subsidiary Tables JI-A •• General PDpuJatJon l'ableB n-B General Economic Tables lI-C Social and Cu1tural Tables II-D Migration Table. nI .. Establishment-Report and Tables IV •• Housing-Report Bnd Tables V Scheduled Castes and Schedule~ Tribes 'in Mabarashtra-TabJe. VI-A Town Directory VI-B Special Survey Reports on Selected Towns VI-C Survey Reports on Selected Villages VII Report on Graduates 8nd Technical Personnel VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration (For ofticial::jJse.. OIQ"Y{'- VIU-B Administration Report-TabulatioD ( For o:ilifi:ial u~,o~\ IX Censul Atla. of Maharasbtta State GOfer_cat Publication. 26 Volumes of Datric:t CCDIIUI HaDilbDob in English 26 Volumes of District Census Handbooks in Marathi Alphabetical List of Villages in Maharashtra (iD Marathi ) IMTRODV"CT10N This is the third edition of district census han4'boob brought Ollt laJ'!C"Iy on the bam of the material collected. -

MAHARASHTRA Not Mention PN-34

SL Name of Company/Person Address Telephone No City/Tow Ratnagiri 1 SHRI MOHAMMED AYUB KADWAI SANGAMESHWAR SANGAM A MULLA SHWAR 2 SHRI PRAFULLA H 2232, NR SAI MANDIR RATNAGI NACHANKAR PARTAVANE RATNAGIRI RI 3 SHRI ALI ISMAIL SOLKAR 124, ISMAIL MANZIL KARLA BARAGHAR KARLA RATNAGI 4 SHRI DILIP S JADHAV VERVALI BDK LANJA LANJA 5 SHRI RAVINDRA S MALGUND RATNAGIRI MALGUN CHITALE D 6 SHRI SAMEER S NARKAR SATVALI LANJA LANJA 7 SHRI. S V DESHMUKH BAZARPETH LANJA LANJA 8 SHRI RAJESH T NAIK HATKHAMBA RATNAGIRI HATKHA MBA 9 SHRI MANESH N KONDAYE RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 10 SHRI BHARAT S JADHAV DHAULAVALI RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 11 SHRI RAJESH M ADAKE PHANSOP RATNAGIRI RATNAGI 12 SAU FARIDA R KAZI 2050, RAJAPURKAR COLONY RATNAGI UDYAMNAGAR RATNAGIRI RI 13 SHRI S D PENDASE & SHRI DHAMANI SANGAM M M SANGAM SANGAMESHWAR EHSWAR 14 SHRI ABDULLA Y 418, RAJIWADA RATNAGIRI RATNAGI TANDEL RI 15 SHRI PRAKASH D SANGAMESHWAR SANGAM KOLWANKAR RATNAGIRI EHSWAR 16 SHRI SAGAR A PATIL DEVALE RATNAGIRI SANGAM ESHWAR 17 SHRI VIKAS V NARKAR AGARWADI LANJA LANJA 18 SHRI KISHOR S PAWAR NANAR RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 19 SHRI ANANT T MAVALANGE PAWAS PAWAS 20 SHRI DILWAR P GODAD 4110, PATHANWADI KILLA RATNAGI RATNAGIRI RI 21 SHRI JAYENDRA M DEVRUKH RATNAGIRI DEVRUK MANGALE H 22 SHRI MANSOOR A KAZI HALIMA MANZIL RAJAPUR MADILWADA RAJAPUR RATNAGI 23 SHRI SIKANDAR Y BEG KONDIVARE SANGAM SANGAMESHWAR ESHWAR 24 SHRI NIZAM MOHD KARLA RATNAGIRI RATNAGI 25 SMT KOMAL K CHAVAN BHAMBED LANJA LANJA 26 SHRI AKBAR K KALAMBASTE KASBA SANGAM DASURKAR ESHWAR 27 SHRI ILYAS MOHD FAKIR GUMBAD SAITVADA RATNAGI 28 SHRI -

Annual Report 2009 10

MMAAHHAARRAASSHHTTRRAA WWAATTEERR RREESSOOUURRCCEESS RREEGGUULLAATTOORRYY AAUUTTHHOORRIITTYY Annual Report 2009 ─ 10 Stake Holder Consultation meeting to discuss Approach Paper on Developing Regulation for Bulk Water Pricing at Kolhapur on 25/05/2009 Dr. Mihir Shah, Member, Planning Commission, Govt. of India visited the Authority on 18/02/2010 Inaugural address by Shri. Ajit Nimbalkar at the State Level Workshop held at Pune on 21/01/2010 to discuss revised Approach Paper & draft Criteria for bulk water tariff MMAHARASHTRA WWATER RRESOURCES RREGULATORY AAUTHORITY (MWRRA) ANNUAL REPORT 2009 – 10 CONTENTS Sr. SUBJECT PAGE No. From To 1. Maharashtra Water Resources Regulatory 1 3 Authority, Act 2005 2. Organisation and Recruitment / Appointments 3 5 in 2009 – 10 3. Activities of the Authority in 2009 – 10 5 - 3.1. Entitlements 5 6 3.2. Bulk Water Tariff 6 7 3.3. Integrated State Water Plan 7 8 3.4. Clearance of New Projects 8 - 3.5. Development of Web Site 8 9 4. Formal Meetings of The Authority 10 - 5. Visit of Dignitaries to The Authority 10 - 6. Important Meetings 10 11 7. Appointment of Legal Consultant 12 - Sr. SUBJECT PAGE No. From To 8. Seminar / Conferences Attended by MWRRA 12 - Officers 9. Library 12 - 10. Accounts, Audit & Procurement 12 14 11. Irrigation Backlog 14 15 12. Action Plan 2010 – 11 15 - Annexure 1. Organogram 17 - 2. Pilot Projects for Entitlement For The Year 2009 19 22 – 10 3(1). Projects Cleared by MWRRA Under Section 11 23 24 (f) of the MWRRA Act 3(2). Projects Cleared for Keeping on Shelf. 25 - 4. Seminar / Workshops Attended by Hon. -

Rapid Environment Impact Assessment Report

KIHIM RESORT Rapid Environment Impact Assessment Report M R . GAUTAM CHAND Project Proponent +91 98203 39444 [email protected] MOEFCC Proposal No.:IA/MH/MIS/100354/2019 18 A p r i l , 2019 Project Proponent: Rapid Environment Impact Assessment Report for CRZ MCZMA Ref. No.: Mr. Gautam Chand (Individual) Proposed Construction of Holiday Resort CRZ-2015/CR-167/TC-4 Village: Kihim, Taluka: Alibag, District: Raigad, MOEFCC Proposal No.: State: Maharashtra, PIN: 402208, Country: India IA/MH/MIS/100354/2019 CONTENTS Annexure A from MOEFCC CRZ Meeting Agenda template 6 Compliance on Guidelines for Development of Beach Resorts or Hotels 10 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 13 1.1 Preamble 13 1.2 Objective and Scope of study 13 1.3 The Steps of EIA 13 1.4 Methodology adopted for EIA 14 1.5 Project Background 15 1.6 Structure of the EIA Report 19 CHAPTER 2: PROJECT DESCRIPTION 20 2.1 Introduction 20 2.2 Description of the Site 20 2.3 Site Selection 21 2.4 Project Implementation and Cost 21 2.5 Perspective view 22 2.5.1 Area Statement 24 2.6 Basic Requirement of the Project 24 2.6.1 Land Requirement 24 2.6.2 Water Requirement 25 2.6.3 Fuel Requirement 26 2.6.4 Power Requirement 26 2.6.5 Construction / Building Material Requirement 29 2.7 Infrastructure Requirement related to Environmental Parameters 29 2.7.1 Waste water Treatment 29 2.7.1.1 Sewage Quantity 29 2.7.1.2 Sewage Treatment Plant 30 2.7.2 Rain Water Harvesting & Strom Water Drainage 30 2.7.3 Solid Waste Management 31 2.7.4 Fire Fighting 33 2.7.5 Landscape 33 2.7.6 Project Cost 33 CHAPTER 3: DESCRIPTION -

Reading Samanth Subramanian's Nonfiction Following Fish

================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 18:6 June 2018 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ================================================================ Travel Literature Transgresses Cultures and Boundaries: Reading Samanth Subramanian’s Nonfiction Following Fish Dr. Gurpreet Kaur, Ph.D., M. Phil., M.A., B.Ed. =========================================================== Courtesy: https://www.amazon.in/Following-Fish-Samanth-Subramanian/dp/0143064479 Abstract Travel literature intends to put to record usually the personal experiences of an author touring a place for the pleasure of travel or intentionally for the purpose of research transgressing the cultural, social, racial, ethnic, religious and gender based boundaries that exist among humanity. Travel writing is another genre that has, as its focus, accounts of real or imaginary places. The genre encompasses a number of styles that may range from the documentary to the evocative, from literary to journalistic, and from the humorous to the serious. It is a form whose ==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 18:6 June 2018 Dr. Gurpreet Kaur, Ph.D., M. Phil., M.A., B.Ed. Travel Literature Transgresses Cultures and Boundaries: Reading Samanth Subramanian’s Nonfiction Following Fish 55 contours are shaped by places and their histories. Critical reflection on travel literature, however, is a relatively new phenomenon. Moreover in this context, India remains a land of deserts, mountains and plains in most imaginations. Only a few of the stories about India explore its vast rivers actually mention its coasts. This paper aims at exploring an Indian journalist turned writer, Samanth Subramanian’s nonfiction, Following Fish: Travels Around The Indian Coast (2010). -

Conference Brochure

Conference Brochure 15th Asian Australasian Congress of Neurological Surgeons, 68th Annual Conference of The Neurological Society of India, International Meningioma Society Congress & World Academy of Neurological Surgery (Members only, December 3-4 2019) with 40th Annual Conference of Society of Indian Neuroscience Nurses (SINN) (December 5-6 2019) Guest Societies: American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS) European Association of Neurological Surgeons (EANS) Venue: Renaissance Mumbai Convention Centre Hotel, Powai, Mumbai www.aasns.nsi2019.org www.aasns.nsi2Ol.org "Message" Dear Friends, th th It gives us great pleasure in welcoming you to the Joint Meeting of the 15 AACNS and 68 NSI th th between December 5 ~ 8 , 2019 in Mumbai. This is the first time that the 4 - yearly Asian Australasian Congress of Neurological Surgeons (AACNS) is coming to India. The Neurosurgical Community of India is leaving no stone unturned to make this a memorable meeting and has thus joined the 68 th Annual Conference of Neurological Society of India (NSI) along with the 15th Continental Congress of Asian Australasian Society of Neurological Surgeons.along with the continental congress of Asian Australasian Society of Neurological Surgeons (AASNS). We are delighted that the International Meningioma Society (IMS) will join us with their Congress. The World Academy of Neurological Surgery Interim Meeting (Members only) will precede our Congress between December rd th 3 ~ 4 , 2019. It is our pleasure to welcome the Guest Societies AANS and EANS and hope that this will be ∼The∼ Neurosurgery Congress of 2019. The theme of this congress is •Towards One World•. In spite of the tremendous progress in the field of neurosurgery in our continent, the standard of care is still very variable. -

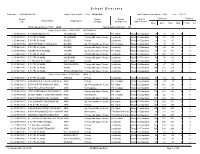

S C H O O L D I R E C T O

S c h o o l D i r e c t o r y State Name : MAHARASHTRA District Code & Name : 2714 YAVATMAL Total Schools in this district : 3165 Year : 2011-12 School School School Location & Enrolment Teachers Code School Name Village Name Category Management Type of School Boys Girls Total Male Female Total Block Code & Name: 271401 ARNI Total Schools in this block : 185 Cluster Code & Name: 2714010003 ANJANKHED 1 27140100802 R. TAGOR VIDYALAYA ANJANKHED No Response Pvt. Aided Rural Co-Educational 27 38 65 4 1 2 27140100801 Z. P. PRI. SCHOOL ANJANKHED Primary with Upper Primary Local body Rural Co-Educational 53 55 108 4 1 3 27140102901 Z. P. PRI. SCHOOL DAHELI Primary Local body Rural Co-Educational 33 32 65 1 1 4 27140103002 LATE SURTIBAI C. VIDYALAYA DATODI Up. Primary with sec./H.sec Pvt. Unaided Rural Co-Educational 45 34 79 1 1 5 27140103001 Z. P. PRI. SCHOOL DATODI Primary with Upper Primary Local body Rural Co-Educational 72 48 120 4 0 6 27140103902 ICHORA HIGH SCHOOL ICHORA Up. Primary with sec./H.sec Pvt. Aided Rural Co-Educational 55 46 101 2 0 7 27140103901 Z. P. PRI. SCHOOL ICHORA Primary with Upper Primary Local body Rural Co-Educational 138 149 287 3 4 8 27140107801 Z. P. PRI. SCHOOL MALEGAON Primary with Upper Primary Local body Rural Co-Educational 72 70 142 3 1 9 27140107802 Z.P. PRI SCH NILEGAON MALEGAON Primary Local body Rural Co-Educational 9 8 17 2 0 10 27140109201 Z. P. PRI. SCHOOL RANIDHANORA Primary with Upper Primary Local body Rural Co-Educational 98 87 185 4 1 11 27140110001 Z. -

Providing Infrastructure to Facilitate Ro-Ro Services and Construction of Breakwater at Mandawa Kaikade Jay Arun, Subba Rao2, Jaffar Patel N.3

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 9, Issue 4, April-2018 112 ISSN 2229-5518 Providing Infrastructure To Facilitate Ro-Ro Services And Construction Of Breakwater At Mandawa Kaikade Jay Arun, Subba Rao2, Jaffar Patel N.3 Abstract— Alibaug is located about 120 km south of Mumbai. The distance from Mumbai to Alibaug in 10 Nautical miles which is about an hour ferry ride from where catamaran/ferry services are available to Mumbai, whereas road takes about 31/2 hour to 5 hours to travel. Ferry service from 6AM to 6PM is available thought the year, except during monsoon. Speedboats from the Gateway of India to Mandwa Jetty take roughly 20–25 minutes depending on the weather and can be hired at the Gateway of India. The new jetty installed in 2014 at Mandwa ensures safety of passengers traveling by speedboat. So the Mumbai Maritime Board has decided to construct the RollOn - RollOff (RO-RO) services to reduce the travel time and that too in half the price. This will help people to reach Alibaug in very less time and so this will increase the reach of Mumbai to Alibaug. This will help in increasing the wharf area and keeping the tourist locations alive, as it will become easy to reach, it will attract more and more people and so will the government will generate revenue out of it due to tourism. The present work thus discusses the practical aspects of the construction stages of a breakwater and a jetty and also the practical executional challenges related to it.