The Sound of Queer Diaspora: Sonic Enactments of Filipinx Desire, Loss and Belonging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Banff Centre Annual Report

The Banff Centre Annual Report April 2007 - March 2008 The Banff Centre Annual Report Inspiring Creativity April 2007 - March 2008 Message from the Board Chair and the President Creativity and innovation will drive Alberta and Canada’s future. For 75 years, The Banff Centre has supported healthy communities and fuelled our economy by inspiring creativity and fostering innovation. Our multidisciplinary programs provoke thought, spark debate, and embrace new ideas. In doing so, they nurture tomorrow’s artists and leaders and advance our understanding of the world. The Banff Centre’s programs attract exceptional artists and thinkers, and support the creation and presentation of new performance and art works. By encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration, we foster applied research and the development of innovative processes and products within cultural industries. Our Leadership Development programming explores new methodologies, informed by artistic practice and by the Centre’s inspirational location. Our Mountain Culture programs and events celebrate our human connection to mountain landscapes and explore solutions to global environmental concerns. During 2007-08, the Centre completed the first project in our transformational Banff Centre Revitalization Project. Thanks to significant support from the Governments of Alberta and Canada, and generous donations from corporate, private, and foundation supporters, the Campaign for The Banff Centre exceeded our Phase One Goal, raising $122.2 million in support of new facilities and programming and scholarship endowments. The Banff Centre’s focus on the future in 2007-08 did not compromise our attention on the present. The Centre continued to deliver exceptional programming, consistently achieving high participant satisfaction ratings. We carefully stewarded our resources, and for the sixth consecutive year the Centre achieved a positive financial year end, enabling us to deploy our annual operating contingency funds to capital maintenance priorities. -

Students Cry Foul

Publication Date: 2009-10-22 View PDF Version 2009-10-22 Vol. 160 Issue 6 Contact the Publisher HOME Students cry foul Canadian Federation of Students deny ARTS & CULTURE receiving student petitions A dank night at the Ebar Daniel Bitonti Behind the counter at the Vinyl Café Featured Artist CFS-Ontario, the provincial component of the Canadian Federation of Students, Canada's largest student lobby, said Tuesday that they had not yet received petitions from any student organizers requesting that a Foodstuffs does Taste of referendum be held on the issue of continued membership in CFS-Ontario. Downtown Foraging for colour with Stefan Herda But according to three sworn affidavits obtained by the Ontarion, student organizers at the University of Guelph, Trent University and Carleton University have sent petitions to CFS-Ontario requesting a referendum Local Expression: Interactions with local be held on each campus at the end of March 2010. artists at the Guelph studio tour On each affidavit of service, Robert James Sutton, Process Server of the City of Toronto, made an oath Microbreweries: small in saying that he personally served CFS-Ontario with true copies of the petition by sliding them through the mail size, big on quality slot at CFS-Ontario headquarters on Sept. 29, 2009 at 4:27pm. David Paul Lee, a Notary Public of the Ohbijou, The Acorn and province of Ontario, notarized the three affidavits. The affidavits also included the signatures of 10 per cent of Kite Hill go to church. the student body at each school, a CFS-Ontario defederating requirement. On thin ice Pissoir pilot project "We have not received any petitions to date," said Shelley Melanson, chairperson of CFS-Ontario. -

Justice in Winnipeg Special Four-Page Pullout Begins on Page 9

12 11 / / 11 2009 VOLUME 64 Justice in Winnipeg special four-page pullout begins on page 9 Discovering wrongful convictions Is Manitoba leading the way? NEWS page 9 out on bail, fresh outta jail But now what? NEWS page 11 celebrating someone who cared New book looks at the life of community activist Harry Lehotsky ARTS & CULTURE page 12 02 The UniTer November 12, 2009 www.UniTer.ca We like sports! "There's one thing that looking for listings? Cover Image CAmpUS & CommUNiTy ListiNgS ANd Read about last weekend's will be offensive to volunteer opportuniTies page 5 This mural, located at 518 Maryland Wesmen volleyball and many, many people." mUSiC page 14, FiLm page 15 St., celebrates the life and work of basketball action Galleries ANd Literature page 17 deceased community activist harry Theatre, dANCE ANd ComEdy page 16 Lehotsky. See story on page 12. awardS ANd FiNANCiAL Aid page 18 campUS news page 6 arts & culture page 16 Photo by Mark reimer UNITER STAFF News ManaGinG eDitor Aaron Epp » [email protected] BUSiness ManaGer Maggi Robinson » [email protected] The town that eliminated poverty PrODUcTiOn ManaGer Melody Morrissette [email protected] new data shows » “Kids [that were part cOPy anD styLe eDitor guaranteed income of mincome] stayed Chris Campbell » [email protected] in school longer and Photo eDitor improves quality Cindy Titus » [email protected] people used hospitals of life newS assiGnMenT eDitor less, especially for Andrew McMonagle » [email protected] accidents and newS PrODUcTiOn eDitor SoNya Howard injuries and mental Cameron MacLean » [email protected] volUNTeer STaff health reasons.” arts anD culture eDitor Sam Hagenlocher [email protected] - eveLyn FOrGeT, U OF M » cOMMents eDitor Imagine a town with no poverty. -

Bruce Peninsula

BRUCE PENINSULA PRESS KIT 203 Margueretta Street Toronto, ON Canada M6H 3S4 CONTACT: JULIE BOOTH p. 416 536 2698 | freshlypressedpr.com BRUCE PENINSULA AUX TV / July 27, 2011 http://www.aux.tv/2011/07/bruce-peninsula-announce-the-release-of-sophomore-album-open-flames-get-set-to-tour- the-east-coast/ Bruce Peninsula announce the release of sophomore album ‘Open Flames,’ get set to tour the East coast Nicole Villeneuve After announcing the Bruce Trail Fire Sale including a stop at the Halifax Pop music series earlier this year as a stopgap while Explosion). vocalist Neil Haverty completed cancer treatment and recovery, Toronto’s Bruce Full Tour dates as well as a sneak peek at Peninsula have finally confirmed that their some goosebump-giving music from Open much-anticipated new album Open Flames Flames can be found below. will be released on October 4 via Hand Drawn Dracula. With Haverty’s cancer in remission (he was diagnosed with Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia in December 2010), the band is also set to tour behind the new album and has announced a slew of dates for September (Ontario) and October (the Maritimes, EXCLAIM.CA / July 27, 2011 http://exclaim.ca/News/bruce_peninsula_return_with_open_flames_book_canadian_tour Bruce Peninsula Return with 'Open Flames,' Book Canadian Tour Alex Hudson The last few months have been rough for A press release says that the new disc contains Peninsula tided fans over with Bruce Trail Toronto roots rockers Bruce Peninsula. "10 new, sprawling songs, drawn from the Fire Sale, a series of free digital B-sides that Shortly after finishing their sophomore LP in skin of a drum and sung from deep down in the band released for free via their website. -

Philippine Arts & Social Studies in the Ontario Curriculum

PASSOC Philippine Arts & Social Studies in the Ontario Curriculum GRADE 8 GEOGRAPHY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Authors Marissa Largo, PASSOC Project Consultant & Coordinator, TCDSB Professor Philip Kelly, Geography, York University Professor Patrick Alcedo, Dance, York University Professor Ethel Tungohan, Politics & Social Science, York University Michelle Aglipay, TCDSB Fredeliza De Jesus, TCDSB Christella Duplessis-Sutherland, TCDSB Merle Gonsalves, TCDSB Patt Olivieri, TCDSB Jennilee Santican, TCDSB Special Thanks Rory McGuckin, Director of Education, TCDSB Nick D’Avella, Equity, Diversity, and Indigenous Education, TCDSB Jodelyn Huang, Community Relations Officer, TCDSB Alicia Filipowich, Centre Coordinator, York Centre for Asian Research Alex Felipe, York Centre for Asian Research Art Reproduced with Permission from Alex Humilde, Offhand Pictures Jo SiMalaya Alcampo and Althea Balmes, The Kwentong Bayan Collective The Graphic History Collective Casey Mecija, Ohbijou, Last Gang Records Alex Felipe, York Centre for Asian Research Thanks to the Generous Support of The Toronto Catholic District School Board The York Centre for Asian Research Canadian Heritage Canada 150 Fund York University Canada 150 Fund Social Sciences and Humanities Resesarch Council of Canada Faculty of Liberal Arts and Professional Studies, York University Canada 150 | Unity in Diversity: Fusion of Communities in Canada Out of our deep respect for Indigenous peoples in Canada, we acknowledge that much of our work takes place upon traditional territories. The territories include the Wendat, the Anishinabek Nation, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, and the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nations. We also recognize the contributions and enduring presence of all First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people in Ontario and the rest of Canada. WHAT IS THE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PASSOC PROJECT? Delve into the balikbayan experience, hop onto a jeepney, and try your hand at the Tinikling. -

Download a Volunteer Application Form at Spenceneigh- to the Second Phase, but Katz Turned Convocation Hall at the the University of Winnipeg

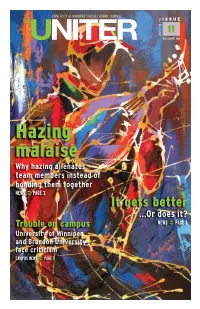

/10 11 2011 / 11 volume 66 Hazing malaise Why hazing alienates team members instead of bonding them together news page 3 It gets better ...Or does it? Trouble on campus news page 3 University of Winnipeg and Brandon University face criticism campus news page 7 02 The UniTer NOvemBer 10, 2011 www.UniTer.ca LookIng for LIsTIngs? Cover Image Wesmen women’s Basic income guarantee CAMPUS & COMMUNITY LISTINGS AND “Sound in Colour” volleyball team off could solve our social VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITIES page 4 By yiSa akinBolaji MUSIC page 12 Mixed-media on canvas, 2009 FILM & LIT page 14 to a hot start assistance woes yisa is a Winnipeg artist who GALLERIES & MUSEUMS pages 14 & 15 immigrated to Canada from nigeria .campus news page6 comments page9 THEATRE, DANCE & COMEDY page 15 in 1997 AWARDS & FINANCIAL AID page 18 Visit www.yisagallery.com PEoPlE Worth ReaDinG aBout UNITER STAFF one small pin ManaGinG eDitor aaron Epp » [email protected] ali Saeed relates his experience as an ethiopian political prisoner and activist BUSiness ManaGer Geoffrey Brown [email protected] ChrIS hUNTer » BeaT reporTer PrODUcTiOn ManaGer ayame Ulrich » [email protected] cOPy anD styLe eDitor Torture, imprisonment and death sentences Britt Embry » [email protected] were amongst the tribulations Ali Saeed and Photo eDitor other members of the Ethiopian People’s Revo- Dylan Hewlett » [email protected] lutionary Party (EPRP) endured when living in Ethiopia. newS assiGnMenT eDitor On Nov. 16, Saeed will travel to Washing- Ethan Cabel » [email protected] ton, D.C., from his home in Winnipeg to speak newS PrODUcTiOn eDitor about Ethiopian human rights violations at the Matt Preprost » [email protected] EPRP 39th Anniversary conference. -

News Niagara

http://www.newsatniagara.com Marchnews 16, 2007 FREE Volume 37, Issue 11 niagara@ See pg. 4 The Best Way To Connect With Niagara See pg. 19 LookingLooking forfor futurefuture starsstars It was a festive line of Denis Morris Secondary School’s actors in The Pile from Niagara Sears District Drama Festival that ran Feb. 19 to Feb. 23 at Brock University in St. Catharines. The event featured 18 performances by 16 high schools from Niagara’s public and Catholic school boards. Natalie Mastracci won an award for distinctive merit as lead role, acting. The Pile also won for best Canadian play as a district award and an award of excellence for adapation. For full reports on the overall winners and other participants, see page 26. Photo by Shawn Dixon SAC welcomes changes Niagara offers By KELLY ESSER past year, one being the U>Pass vote, INDEX Staff Writer an arrangement with municipal public literacy program Niagara College’s Student Administra- transportation networks for a student- tive Council (SAC) will be seeing some oriented travel pass. By LESLEY SMITH Workforce and Business Devel- Travel pg. 3 changes next year. “[This helps] make the college more Staff Writer opment division. “Some of our On Feb. 15, SAC members gathered in accessible,” says Elsie Vrugteveen, Diplomas are not all the col- students receive English and Editorials pg. 8 After Hours at the Welland campus for Niagara-on-the-Lake SAC president. lege has to offer students. math tutoring in the evening, the annual general meeting, to discuss Vrugteveen also thanked Jennifer The Literacy and Basic Skills and it has made a signifi cant Columns pg. -

Save Our Downtown Mrp Final

“SAVE OUR DOWNTOWN”: INDIE MUSIC’S CONTRIBUTION TO LOCAL CULTURE, COMMUNITY BUILDING, AND URBAN REGENERATION IN TWO SMALL ONTARIO CITIES MIKA POSEN A MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO AUGUST, 2012 ©Mika Posen AUGUST, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 - BRANTFORD AND THE FORD PLANT......................................................7 1.1 Brantford...........................................................................................................................7 1.2 The Ford Plant.................................................................................................................10 CHAPTER 2 – SARNIA AND EMPTY SPACES.................................................................20 2.1 Sarnia ..............................................................................................................................20 2.2 Empty Spaces..................................................................................................................21 CHAPTER 3 – LOCAL MUSIC: VALUE AND POTENTIAL............................................28 CHAPTER 4 – INDIE MUSIC...............................................................................................36 4.1 A Brief History of Indie Music ........................................................................................36 -

Music 96676 Songs, 259:07:12:12 Total Time, 549.09 GB

Music 96676 songs, 259:07:12:12 total time, 549.09 GB Artist Album # Items Total Time A.R. Rahman slumdog millionaire 13 51:30 ABBA the best of ABBA 11 43:42 ABBA Gold 9 36:57 Abbey Lincoln, Stan Getz you gotta pay the band 10 58:27 Abd al Malik Gibraltar 15 54:19 Dante 13 50:54 Abecedarians Smiling Monarchs 2 11:59 Eureka 6 35:21 Resin 8 38:26 Abel Ferreira Conjunto Chorando Baixinho 12 31:00 Ace of Base The Sign 12 45:49 Achim Reichel Volxlieder 15 47:57 Acid House Kings Sing Along With 12 35:40 The Acorn glory hope mountain 12 48:22 Acoustic Alchemy Early Alchemy 14 45:42 arcanum 12 54:00 the very best of (Acoustic Alchemy) 16 1:16:10 Active Force active force 9 42:17 Ad Vielle Que Pourra Ad Vielle Que Pourra 13 52:14 Adam Clayton Mission Impossible 1 3:27 Adam Green Gemstones 15 31:46 Adele 19 12 43:40 Adele Sebastan Desert Fairy Princess 6 38:19 Adem Homesongs 10 44:54 Adult. Entertainment 4 18:32 the Adventures Theodore And Friends 16 1:09:12 The Sea Of Love 9 41:14 trading secrets with the moon 11 48:40 Lions And Tigers And Bears 13 55:45 Aerosmith Aerosmith's Greatest Hits 10 37:30 The African Brothers Band Me Poma 5 37:32 Afro Celt Sound System Sound Magic 3 13:00 Release 8 45:52 Further In Time 12 1:10:44 Afro Celt Sound System, Sinéad O'Connor Stigmata 1 4:14 After Life 'Cauchemar' 11 45:41 Afterglow Afterglow 11 25:58 Agincourt Fly Away 13 40:17 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir Saint Hubert 11 38:26 Ahmad El-Sherif Ben Ennas 9 37:02 Ahmed Abdul-Malik East Meets West 8 34:06 Aim Cold Water Music 12 50:03 Aimee Mann The Forgotten Arm 12 47:11 Air Moon Safari 10 43:47 Premiers Symptomes 7 33:51 Talkie Walkie 10 43:41 Air Bureau Fool My Heart 6 33:57 Air Supply Greatest Hits (Air Supply) 9 38:10 Airto Moreira Fingers 7 35:28 Airto Moreira, Flora Purim, Joe Farrell Three-Way Mirror 8 52:52 Akira Ifukube Godzilla 26 45:33 Akosh S. -

Beats and Braids Artist Bios

Beats and Braids Artist Bios NATHAN ADLER is a writer, artist, and filmmaker. His novel Wrist, an Indigenous monster story, is published by Kegedonce Press (July 2016). He has a short story published in The playground of Lost Toys (Dec. 2015), and two forthcoming stories: Tyner's Creek in an anthology called Those Who Make Us ~ Canadian Creatures, Monsters and Myth, by Exile Editions; and, Valediction at The Star View Motel, in an Anthology called Love Beyond Body, Space, and Time, by Bedside Press. He is an MFA candidate in the Creative Writing program at UBC and works as a glass-artist. He is also working on a collection of short- stories and a second novel. He is Anishinaabe and Jewish, and a member of Lac Des Mille Lacs First Nation. SEAN CONWAY is an entertainer from Curve Lake First Nation, currently residing in Peterborough, Ontario. He is an avid musical explorer bridging classic country music, rockabilly and jazz as a guitarist, singer, songwriter and bandleader. From his stark intensity to his relentless humour, he takes his audience through his shows with grace and poignance. Come see him by himself, or with his band - Either way this lovely performer is sure to make you laugh, dance and carry-on. ANN BEAM has been a professional artist for more than 30 years, with a BA in Fine Art from State University of New York at Buffalo. She taught at the Art Gallery of Ontario and has worked extensively in a wide range of media including ceramics, watercolour, etching, concrete, canvas, as well as works on paper. -

The Cord Weekly (March 7, 2007)

The Cord Weekly The tie that binds since 1926 GLOBAL GIRL POWER STUDENTS TAKE PARKINSON'S Angela Merkel is among the world's Groundbreaking research and rehabilitation is female powerhouses... PAGE 8 happening just up the street... PAGE 16-17 Volume 47 Issue 24 WEDNESDAY MARCH 7,2007 www.cordweekly.com Second time's a charm Students WLUSU grill director hopefuls at second open forum yesterday; board and election awareness reigns as hot topic Photos by Sydney Helland VOTE FOR ME - Above, 5 of the now 12 SGM candidates tackle student questions. L to R: Colin LeFevre, Heather Blair, Justin Veenstra, Sheena Carson, Asif Bacchus. STEVE NILES friends, supporters and current due to her commute from Hamil- the ideas stated intheir platforms. running for vice president: univer- STAFF WRITER directors. is Whenthe until he forced ton. Henderson seeking a spot floor was opened, cur- sity affairs was to will Director candidates com- on the Waterlooboard despite be- rent director Jonathan Champagne withdraw due to pneumonia, Asif The final of the for five board that Bacchus made admitted stage second 2007 pete empty spots ing a commuter student attending asked candidates \vhy they had an paper- election took after lacklustre Brantford work that stalled his WLUSU campaign were reopened in- campus. not run in the previous election, error applica- Veenstra place Tuesday with a sparsely at- terest in WLUSU's annual election She explained that being located one that resulted in an acclaimed tion, and Justin was serv- tended board of directors forced the students' unionto hold a at the Brantford will board. -

Ontario, 2007-08

Canada Council for the Arts Funding to artists and arts organizations in Ontario, 2007-08 For more information or additional copies of this document, please contact: Research Office 350 Albert Street. P.O. Box 1047 Ottawa ON Canada K1P 5V8 (613) 566-4414 / (800) 263-5588 ext. 4526 [email protected] Fax (613) 566-4428 www.canadacouncil.ca Or download a copy at: http://www.canadacouncil.ca/publications_e This publication is a companion piece to the Annual Report of the Canada Council for the Arts 2007-08. www.canadacouncil.ca/annualreports Publication aussi offerte en français Research Office – Canada Council for the Arts Table of Contents 1.0 Overview of Canada Council funding to Ontario in 2007-08 ................................................................... 1 2.0 Statistical highlights about the arts in Ontario ............................................................................................. 2 3.0 Highlights of Canada Council grants to Ontario artists and arts organizations ................................ 3 4.0 Overall arts and culture funding to Ontario by all three levels of government ................................ 8 5.0 Detailed tables of Canada Council funding to Ontario ........................................................................... 11 List of Tables Table 1: Government expenditures on culture, to Ontario, 2003-04 ............................................................. 9 Table 2: Government expenditures on culture, to all provinces and territories, 2003-04 ......................9 Table