Gender, Class and Nation in the Foothills Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The ICFAI University, Dehradun

The ICFAI University, Dehradun Dehradun An exclusive Guide by The ICFAI University Dehradun Answered questions Get the latest answers on cutoff, courses, placements, admission, fees, ranking & eligibility. All answers have been submitted by students, alumni & experts. Which colleg e is better among Dehradun Law Colleg e, Chandig arh University and ICFAI University, Dehradun? 10 Answers . 838 Views SHWET A BHARDWAJ 4 weeks ago S Beg inner-Level 1 ICFAI University Dehradun is better then Chandigarh University in all a spects but when compared to the other Dehradun law schools, ICFAI Law school stands out at the top. It gives different course and choic e of subjects in legal studies and help students to choose a rightful path. The faculty is highly trained and all have excess to the library w hich is stocked with more then 10000 books. Which colleg e is better IBS, Dehradun or Doon Business School or Graphic Era in terms of placements and academics? Please help me out. 8 Answers . 531 Views DEBANJANA ROY a mo nth ago D Beg inner-Level 1 Disclaimer: This PDF is auto-generated based on the information available on Shiksha as on 24-Sep-2021. Hello Darshana, I can only give you an insight into IBS Dehradun as I am presently stu dying there. You can yourself compare different genuine reviews of t he mentioned colleges and make your own judgement. Firstly ICFAI Business School (IBS) , Dehradun offers M.B.A degree wh ich carries more value than PGDM Degree . If you do PGDM you won' t be able to do Phd if suddenly you feel you have the potential to act ually put Doctorate before your name. -

OUTCOME BUDGET DOON UNIVERSITY Dehradun

OUTCOME BUDGET 2012-13 DOON UNIVERSITY Dehradun Mothrowala Road, Kedarpur P.O. Ajabpur Dehradun-248001 Uttarakhand Doon University, Outcome Budget, 2012-13 Page 1 Doon University, Dehradun Outcome Budget 2012-13 1. About The University Doon University draws its profile from the vision of the State to transform the higher education of the region by creating centres of excellence. The Government of Uttarakhand approved the establishment of a University in 2005 vide Uttararanchal Adhiniyam Sankhya 18 of 2005 that would become a centre of higher learning in contemporary disciplines. The main campus of the University is located in an area of 22.26 hectares at Kedarpur, Dehradun. A second campus is proposed to be established on 40.47 hectares of land at Sahaspur. Doon University is a residential University. Students are expected to stay in the Hostel in the Campus as they will be required to participate in group discussions and attend tutorials after the regular classes are over which will help the student to clarify any doubts in the courses and improve their interpersonal and communication skills. The University is supported and funded by the State Government for its financial requirements under the recurring and non-recurring expenditures. The University has now obtained 12(B) Status under the UGC Act of 1956 and has now become eligible to obtain Development Assistance from University Grants Commission. Vision, Mission and Character of the University Vision of the University In accordance with the provision in Section 5(1) of the Act No 18 of 2005, Doon University shall become a Centre of Excellence in the chosen areas of studies, and shall carry out research for the advancement and dissemination of knowledge. -

No Short Cut to Success Is the Mantra for 2018 At

Editorial It is start of a fresh new year. We all have already wel - No Short Cut To Success is the comed 2018 in our own style. Some of us have partied to part ways with 2017 while some of us started our year by praying to the almighty to fulfill our wishes and give us A clear vision isM must faor any intstirtutiaon i f ift haos tor ex ce2l bo0th lo1ng t8erm aAnd shtor t tHerm. HZimgiUri Zee University best result in the future. Many of us have also set our that was founded on the philosophy of excellence in education has taken some steps forward in the direction in goals for 2018 and the years beyond so that we can make 2017 and plans to do so in 2018 and the years ahead. To understand this vision of the University Ankita Uniyal the best of what lies ahead of us. spoke with Dr. Rakesh Ranjan Vice Chancellor Himgiri Zee University. Edited Excerpts: We all might differ in our reasons and approach towards welcoming a fresh new year but we are all trying to ad - dress one big question in front of us. The question being – How to make our lives better by achieving that we all desire to? Yes, the first person of the University the Vice Chancellor has answered your question by putting it thus, he says, ‘there is no short cut to success and hard work is must if we wish to succeed in our endeavors This stands true for us even more so as we are all part of a coveted academic institution and with us lie the respon - sibility of building the nation as we are the porters of the nation. -

Convocation || Issue Dec 2018 ||

SPECIAL EDITION: CONVOCATION || ISSUE DEC 2018 || THEREFLECTIONOFLIFE Pratibimb -The reflection of life “Success is the result of perfection, hard work, learning from failure loyalty and persistence”- Collin Powell. Pratibimb, The Reflection of Life, took gallons of enthusiasm, efforts and creative deluge of thoughts. It has today manifested into a form that vividly brings forth the reflections of life... Like every year the team of Pratibimb starts with the mammoth task of putting forth the ideas and thoughts of our peers together. As the gears started to move, things began to shape up and with each passing day we were coming close to the final outlook of the magazine. Eventually all the hard work and effort paid off in the form of this year’s edition of Pratibimb. Months of effort and dedication towards completing this magazine has brought us this well-deserved treat. We hope you enjoy browsing through this December 2018 issue of Pratibimb. Advisory Board Mr. Anuj Aggarwal, Chairman Prof. N. Ravi Shanker, Chancellor Prof. Kuldeep Kumar Raina, Vice Chancellor Prof . Brigadier M. Srinivasan, Pro Vice Chancellor Mr. Akshay Ghorpade, Public Relation Officer Editor- in Chief Dr. Sakshi Semwal Managing Editor Dr. Shachi Negi Student Editors Poorva Tiwari, CSE- CSF, IInd yr. (Head) Alukik Varun CSE-BDA, IInd yr. Raghav Bahuguna, BSC Physics Ist yr. Summanya, B.A English Hons. Ist yr. Ritika Manchanda, B.A English Hons. Ist yr. Yatharth Swaroop CSE- CSF, Ist yr. Akshat CSE-B Ist yr. Designing Head Ar. Rick Dé Designing Team Ar. Idha Sharma Aayush Saini, BCA IInd Year Sanat, BCA IInd Year Hemesh Khilani CSE- CSF, IInd yr. -

Making Way: Securing the Chilla-Motichur Corridor to Protect

OCCASIONAL REPORT NO. 10 MAKING WAY Till recent past the elephant population of Chilla on the east bank of the Ganga and Motichur, on the west, was one with regular movement between these two forest ranges of Rajaji National Park. Securing the Chilla-Motichur Corridor This movement, at one point, came to a virual halt because of to protect elephants of Rajaji National Park manmade obstacles like the Chilla power channel, an Army ammunition dump and rehabilitation of Tehri dam evacuees. The Eds: Vivek Menon, PS Easa and AJT Johnsingh problem was compounded by accidents owing to the railway track that passes through the area as National highway (NH 72). This study looks at WTI’s initiative in both securing the corridor as well as eliminating rail-hit incidents. B-13, Second floor, Sector - 6, NOIDA - 201 301 Uttar Pradesh, India Tel: +91 120 4143900 (30 lines) Fax: +91 120 4143933 Email: [email protected], Website: www.wti.org.in Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), is a non-profit conservation organisation, committed to help conserve nature, especially endangered species and threatened habitats, in partnership with communities and governments. Its vision is the natural heritage of India is secure. Project Team Suggested Citation: Menon, V; Easa,P.S; Johnsingh, A.J.T (2010) ‘Making Ashok Kumar Way’ - Securing the Chilla-Motichur corridor to protect elephants of Rajaji National Park. Wildlife Trust of India, New Delhi. Vivek Menon Aniruddha Mookerjee Keywords: Encroachment, Degradation, Sand mining, Corridor, Khand Gaon, P.S Easa Rehabilitation, Rajaji National Park, Anil Kumar Singh The designations of geographical entities in this publication and the A J T Johnsingh presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the authors or WTI concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries Editorial Team All rights reserved. -

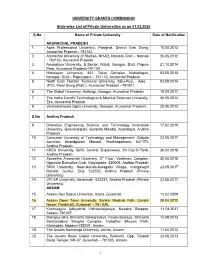

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION State-Wise List of Private

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION State-wise List of Private Universities as on 01.02.2020 S.No Name of Private University Date of Notification ARUNACHAL PRADESH 1. Apex Professional University, Pasighat, District East Siang, 10.05.2013 Arunachal Pradesh - 791102. 2. Arunachal University of Studies, NH-52, Namsai, Distt – Namsai 26.05.2012 - 792103, Arunachal Pradesh. 3. Arunodaya University, E-Sector, Nirjuli, Itanagar, Distt. Papum 21.10.2014 Pare, Arunachal Pradesh-791109 4. Himalayan University, 401, Takar Complex, Naharlagun, 03.05.2013 Itanagar, Distt – Papumpare – 791110, Arunachal Pradesh. 5. North East Frontier Technical University, Sibu-Puyi, Aalo 03.09.2014 (PO), West Siang (Distt.), Arunachal Pradesh –791001. 6. The Global University, Hollongi, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 18.09.2017 7. The Indira Gandhi Technological & Medical Sciences University, 26.05.2012 Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh. 8. Venkateshwara Open University, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 20.06.2012 S.No Andhra Pradesh 9. Bharatiya Engineering Science and Technology Innovation 17.02.2019 University, Gownivaripalli, Gorantla Mandal, Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh 10. Centurian University of Technology and Management, Gidijala 23.05.2017 Junction, Anandpuram Mandal, Visakhapatnam- 531173, Andhra Pradesh. 11. KREA University, 5655, Central, Expressway, Sri City-517646, 30.04.2018 Andhra Pradesh 12. Saveetha Amaravati University, 3rd Floor, Vaishnavi Complex, 30.04.2018 Opposite Executive Club, Vijayawada- 520008, Andhra Pradesh 13. SRM University, Neerukonda-Kuragallu Village, mangalagiri 23.05.2017 Mandal, Guntur, Dist- 522502, Andhra Pradesh (Private University) 14. VIT-AP University, Amaravati- 522237, Andhra Pradesh (Private 23.05.2017 University) ASSAM 15. Assam Don Bosco University, Azara, Guwahati 12.02.2009 16. Assam Down Town University, Sankar Madhab Path, Gandhi 29.04.2010 Nagar, Panikhaiti, Guwahati – 781 036. -

Trends, Issues and Women in Hospitality and Tourism Industry

SCHOOL OF HOTEL MANAGEMENT & HOSPITATLITY Trends, Issues and Women in Hospitality and Tourism Industry SPONSORS IN COLLABORATION WITH SPONSORS Accredited by NAAC with Grade A SCHOOL OF HOTEL MANAGEMENT & HOSPITATLITY Trends, Issues and Women in Hospitality and Tourism Industry IN COLLABORATION WITH ORGANIZERS SCHOOL OF HOTEL MANAGEMENT & HOSPITALITY, GRAPHIC ERA UNIVERSITY SPONSORS Accredited by NAAC with Grade A SCHOOL OF HOTEL MANAGEMENT & HOSPITATLITY Trends, Issues and Women in Hospitality and Tourism Industry IN COLLABORATION WITH ORGANIZERS SCHOOL OF HOTEL MANAGEMENT & HOSPITALITY, GRAPHIC ERA UNIVERSITY GRAPHIC ERA UNIVERSITY Graphic Era University, Dehradun has been a pioneer in the Field of Education as well as in reviving cultures and promoting the state of Uttarakhand. It has been s a centre for research and specialized studies, an institution that has created engineers, managers, technocrats and entrepreneurs with a world class rating. GEU has been appreciated over the years by owing to its excellent education services .Graphic Era University has been awarded "A" grade from National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC). Please visit our website www.geu.ac.in for further details. SCHOOL OF HOTEL MANAGEMENT AND HOSPITALITY Department of hotel management was established in the year 2004 keeping in mind the need for providing quality skilled manpower for hospitality industry. Since then the department continues to prepare dedicated industry professionals and focuses on training the students in a way that they meet head on challenges of the hotel industry. The “The best way Department of Hotel management has been upgraded to School of Hotel management and Hospitality from the year 2015.The School of Hotel to find yourself is to lose management and Hospitality (SOHMH) offers 1 year Certificate course in Hotel and Hospitality Management, 4 years degree under the course yourself in the service of Bachelor of Hotel Management and also offer PhD in Hotel Management. -

6.3.3 Annual Report 2015-16.Pdf

From the Chancellor’s Desk .................................................................................. 4 From the Vice-Chancellor’s Desk ......................................................................... 5 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 6 2. Vision & Mission ............................................................................................. 6 3. Governance ..................................................................................................... 6 • Organogram ............................................................................................ 7 • Officers of the University ..................................................................... 8 • Authorities of the University ............................................................... 8 • Members of the University.................................................................. 8 4. Accreditations ................................................................................................. 9 5. Campus and Infrastructure ........................................................................ 10 6. Faculties and Programs ............................................................................... 11 7. Distance Education Programs .................................................................... 20 8. Resources and Facilities .............................................................................. 22 9. Faculty Resources and Support Staff -

Consolidated List Private Universities

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION State-wise List of Private Universities as on 06.08.2021 S.No Name of Private University Date of Notification ARUNACHAL PRADESH 1. Apex Professional University, Pasighat, District East Siang, 10.05.2013 Arunachal Pradesh - 791102. 2. Arunachal University of Studies, NH-52, Namsai, Distt – Namsai 26.05.2012 - 792103, Arunachal Pradesh. 3. Arunodaya University, E-Sector, Nirjuli, Itanagar, Distt. Papum 21.10.2014 Pare, Arunachal Pradesh-791109 4. Himalayan University, 401, Takar Complex, Naharlagun, 03.05.2013 Itanagar, Distt – Papumpare – 791110, Arunachal Pradesh. 5. North East Frontier Technical University, Sibu-Puyi, Aalo 03.09.2014 (PO), West Siang (Distt.), Arunachal Pradesh –791001. 6. The Global University, Hollongi, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 18.09.2017 7. The Indira Gandhi Technological & Medical Sciences University, 26.05.2012 Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh. 8. Venkateshwara Open University, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 20.06.2012 Andhra Pradesh 9. Bharatiya Engineering Science and Technology Innovation 17.02.2019 University, Gownivaripalli, Gorantla Mandal, Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh 10. Centurian University of Technology and Management, Gidijala 23.05.2017 Junction, Anandpuram Mandal, Visakhapatnam- 531173, Andhra Pradesh. 11. KREA University, 5655, Central, Expressway, Sri City-517646, 30.04.2018 Andhra Pradesh 12. Saveetha Amaravati University, 3rd Floor, Vaishnavi Complex, 30.04.2018 Opposite Executive Club, Vijayawada- 520008, Andhra Pradesh 13. SRM University, Neerukonda-Kuragallu Village, mangalagiri 23.05.2017 Mandal, Guntur, Dist- 522502, Andhra Pradesh (Private University) 14. VIT-AP University, Amaravati- 522237, Andhra Pradesh (Private 23.05.2017 University) ASSAM 15. Assam Don Bosco University, Azara, Guwahati 12.02.2009 16. Assam Down Town University, Sankar Madhab Path, Gandhi 29.04.2010 Nagar, Panikhaiti, Guwahati – 781 036. -

The Political Economy of Water Security in Mussoorie, Uttarakhand

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF WATER SECURITY IN MUSSOORIE, UTTARAKHAND Final Project Report Submitted by: Nuvodita Singh In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sustainable Development Practice May 2015 0 DECLARATION This is to certify that the work that forms the basis of this project “The Political Economy of Water Security in Mussoorie, Uttarakhand” is an original work carried out by me and has not been submitted anywhere else for the award of any degree. I certify that all sources of information and data are fully acknowledged in the project report. Signature (Nuvodita Singh) Place and Date 1 Certificate This is to certify that “Nuvodita Singh” has carried out her major project in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Sustainable Development Practice on the topic “The Political Economy of Water Security in Mussoorie, Uttarakhand” during January 2015 to May 2015. The project was carried out at the “Centre for Ecology Development and Research (CEDAR), Dehradun”. The report embodies the original work of the candidate to the best of our knowledge. Date: (Signature) (Signature) Name of the External Supervisor: Name of the Internal Supervisor Dr. Devendra Chauhan Dr. Arabinda Mishra Designation: Senior Fellow Designation: Dean Name of the Organization Name of the Organization: Centre for Ecology Development TERI University and Research (CEDAR) (Signature) Dr. Shaleen Singhal Head of the Department Department of Policy Studies TERI University, New Delhi 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The last 4 months have involved a great deal of work. It has involved new challenges, new learning, new opportunities and experiences. -

Selected Abstract List 11Th UTTARAKHAND STATE SCIENCE and ORAL Presentation TECHNOLOGY CONGRESS 201 6-17 Presenting Author Wise

Selected Abstract List 11th UTTARAKHAND STATE SCIENCE AND ORAL Presentation TECHNOLOGY CONGRESS 201 6-17 Presenting Author wise Presenting Affiliation/ Roll Author* Organization Discipline Cat. Title of Abstract No Department of Hydrology LANDUSE/LANDCOVER CHANGE IN Indian Institute of Technology Engineering Science AGLAR WATERSHED(TEHRI-GARWAL Aamir Ishaq Shah 1 179 Roorkee and Technology DISTRICT, UTTARAKHAND): IS IT Haridwar (UK) MANMADE OR NATURAL Department of Physics H.N.B. Garhwal University DIELECTRIC PROPERTIES OF ORDER- Aanchal Rawat Physics 1 367 Srinagar (Garhwal) DISORDER FERROELECTRIC CRYSTALS Pauri (UK) GC-MS CHARACTERIZATION OF Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry Medical Science ISOLATED FRACTIONS AND Abhay Prakash H.N.B. Garhwal University including 1 ANTIBACTERIAL POTENTIAL OF 289 Mishra Srinagar (Garhwal) Pharmaceutical Science PETROLEUM ETHER EXTRACT FROM Pauri (UK) SAUSSUREA OBVALLATA EFFECT OF DIFFERENT NITRATE School of Environment and Natural CONCENTRATIONS ON THE GROWTH Resourc es Abhijeet D. Environmental Science AND LIPID CONTENT OF CHLORELLA Doon University 2 218 Kadam & Forestry SPECIES AND ITS BIODIESEL Ajabpur PROPERTIES BASED ON FATTY ACID Dehradun (UK) COMPOSITION Centre of Excellence on Forest Based Livelihood in Uttarakhand SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF Uttarakhand State Council for Science and Environmental Science Ajeet Kaur Technology 3 NON-TIMBER FOREST PRODUCTS OF 226 & Forestry Vigyan Dham UTTARAKHAND Jhajra Dehradun (UK) Chemistry Division CHEMICAL CHARACTERISATION OF Aje et Kumar Forest Research -

Best Private Universities Ranking 2021

EDUCATION POST | May-June 2021 | 110 IIRF-2021| BEST PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES tate ame City Zone S N Rank* tate Rank Zone Rank Zone S Preferential Preferential Dhirubhai Ambani Institute of 1 Information and Communication Gandhinagar Gujarat 1 West 1 Technology 2 AMITY University Noida Uttar Pradesh 1 North 1 3 Shiv Nadar University Dadri Uttar Pradesh 2 North 2 4 O.P. Jindal Global University Sonipat Haryana 1 North 3 5 Nirma University Ahmedabad Gujarat 2 West 2 6 Reva University Bangalore Karnataka 1 South 1 7 Azim Premji University Bangalore Karnataka 2 South 2 8 Sri Sri University Bhubaneswar Odisha 1 East 1 9 AMITY University Jaipur Rajasthan 1 North 4 10 ITM University Gwalior Madhya Pradesh 1 Central 1 10 AMITY University Gwalior Madhya Pradesh 1 Central 1 11 Dayanand Sagar University Bangalore Karnataka 3 South 3 12 AMITY University Gurgaon Haryana 2 North 5 Centre for Environmental Planning Ahemdabad Gujarat West 13 and Technology University 3 3 13 Apeejay Stya University Sohna Haryana 3 North 6 14 Chitkara University Patiala Punjab 1 North 7 15 Ahmedabad University Ahmedabad Gujarat 4 West 4 Shoolini University of Biotechnology Solan Himachal Pradesh North 16 and Management Sciences 1 8 *Page 6 (Disclaimer) EDUCATION POST | May-June 2021 | 112 EDUCATION POST | May-June 2021 | 113 IIRF-2021| BEST PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES tate ame City Zone S N Rank* tate Rank Zone Rank Zone S Preferential Preferential University of Petroleum and Energy Dehradun Uttarakhand North 17 Studies (UPES) 1 9 18 Chandigarh University Mohali Punjab 2 North 10