Japanese Mythology: from Traditional Theatre Forms To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Performativity in Japan

IJMSS Vol.04 Issue-09, (September, 2016) ISSN: 2321-1784 International Journal in Management and Social Science (Impact Factor- 5.276) Gender Performativity in Japan Lin Fan I-Shou University No. 1, Section 1, Xuecheng Rd., Dashu District Kaohsiung City, TAIWAN Abstract This paper explores gender issues Japanese daily life or traditional and contemporary shows. Specifically, it looks at gender politics in a number of performing arts, highlighting ways in which humor constructs the feminine. Like eroticism, humor builds on a fascination with the real ambiguity of gender; and reciprocally gender is sensually and humorously fashioned. Humorous performances arise from the aesthetic disturbance or subversion of historically specific gender prescriptions, just as the child develops role-playing strategies to understand what makes a male and a female body, game or activity before assimilating the gender divisions that prevail in her world. Gender is understood in this paper as a sort of unfinished picture that people have fun crafting. Keywords: humor; gender; performance; Japan. A Monthly Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories International Journal in Management and Social Science http://www.ijmr.net.in email id- [email protected] Page 288 IJMSS Vol.04 Issue-09, (September, 2016) ISSN: 2321-1784 International Journal in Management and Social Science (Impact Factor- 5.276) Gender politics in kyōgen and kabuki The classical theatrical genres that are still performed today are known as sarugaku and kabuki. Gaining popularity throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the two types of sarugaku, nō and kyōgen, acquired their present form between the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. -

Girlhood Reimagined: Representations of Girlhood in the Films of Hayao Miyazaki

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Karissa Sabine for the degree of Master of Arts in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies presented on June 8, 2017. Title: Girlhood Reimagined: Representations of Girlhood in the Films of Hayao Miyazaki. Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________ Bradley Boovy Despite the now common usage of the term “girl”, there has been little call for pause and deeper analysis into what we actually mean when we use this term. In particular, animated film provides a wide scope of media texts that claim to focus on girlhood; but how do we in fact know girlhood? How is girlhood constructed? With these questions in mind, I use feminist textual analysis to examine three films— Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), and Princess Mononoke (1997)—by acclaimed Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki in which girl characters and girlhood play prominently into the film's construction as a whole. In particular, I examine how Miyazaki constructs girlhood through his storylines and characters and how these characters (i.e. girls) are then positioned in relation to three specific aspects of their representation: their use of clothing, their relationships to other characters, and their freedom of movement relative to other characters. In doing so, I deconstruct more traditionally held notions of girlhood in which girls are seen as dependent and lacking autonomy. Through Miyazaki’s work, I instead offer up a counternarrative of girlhood in which the very category of gender, and indeed “girls”, are destabilized. In doing so, I hope to provide a wider breadth of individuals the chance to see themselves represented in animated film in both significant and meaningful ways. -

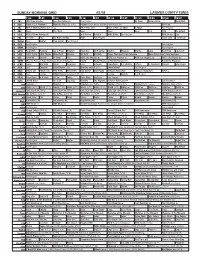

Sunday Morning Grid 4/1/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/1/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program JB Show History Astro. Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Boston Bruins at Philadelphia Flyers. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Misa de Pascua: Papa Francisco desde el Vaticano Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Spirited Away Study Guide

Spirited Away Directed by Hayao Miyazki This study guide suggests cross-curricular activities based on the film Spirited Away by Hanoko Miyazaki. The activities seek to complement and extend the enjoyment of watching the film, while at the same time meeting some of the requirements of the National Curriculum and Scottish Guidelines. The subject area the study guide covers includes Art and Design, Music, English, Citizenship, People in Society, Geography and People and Places. The table below specifies the areas of the curriculum that the activities cover National Curriculum Scottish Guidelines Subject Level Subject Level Animation Art +Design KS2 2 C Art + Investigating Visually and 3 A+B Design Reading 5 A-D Using Media – Level B-E Communicating Level A Evaluating/Appreciating Level D Sound Music KS2 3 A Music Investigating: exploring 4A-D sound Level A-C Evaluating/Appreciating Level A,C,D Setting & English KS2 Reading English Reading Characters 2 A-D Awareness of genre 4 C-I Level B-D Knowledge about language level C-D Setting & Citizenship KS2 1 A-C People People & Needs in Characters 4 A+B In Society Society Level A Japan Geography KS2 2 E-F People & Human Environment 3 A-G Places Level A-B 5 A-B Human Physical 7 C Interaction Level A-D Synopsis When we first meet ten year-old Chihiro she is unhappy about moving to a new town with her parents and leaving her old life behind. She is moody, whiney and miserable. On the way to their new house, the family get lost and find themselves in a deserted amusement park, which is actually a mythical world. -

Title Call # Category

Title Call # Category 2LDK 42429 Thriller 30 seconds of sisterhood 42159 Documentary A 42455 Documentary A2 42620 Documentary Ai to kibo no machi = Town of love & hope 41124 Documentary Akage = Red lion 42424 Action Akahige = Red beard 34501 Drama Akai hashi no shita no nerui mizu = Warm water under bridge 36299 Comedy Akai tenshi = Red angel 45323 Drama Akarui mirai = Bright future 39767 Drama Akibiyori = Late autumn 47240 Akira 31919 Action Ako-Jo danzetsu = Swords of vengeance 42426 Adventure Akumu tantei = Nightmare detective 48023 Alive 46580 Action All about Lily Chou-Chou 39770 Always zoku san-chôme no yûhi 47161 Drama Anazahevun = Another heaven 37895 Crime Ankokugai no bijo = Underworld beauty 37011 Crime Antonio Gaudí 48050 Aragami = Raging god of battle 46563 Fantasy Arakimentari 42885 Documentary Astro boy (6 separate discs) 46711 Fantasy Atarashii kamisama 41105 Comedy Avatar, the last airbender = Jiang shi shen tong 45457 Adventure Bakuretsu toshi = Burst city 42646 Sci-fi Bakushū = Early summer 38189 Drama Bakuto gaijin butai = Sympathy for the underdog 39728 Crime Banshun = Late spring 43631 Drama Barefoot Gen = Hadashi no Gen 31326, 42410 Drama Batoru rowaiaru = Battle royale 39654, 43107 Action Battle of Okinawa 47785 War Bijitâ Q = Visitor Q 35443 Comedy Biruma no tategoto = Burmese harp 44665 War Blind beast 45334 Blind swordsman 44914 Documentary Blind woman's curse = Kaidan nobori ryu 46186 Blood : Last vampire 33560 Blood, Last vampire 33560 Animation Blue seed = Aokushimitama blue seed 41681-41684 Fantasy Blue submarine -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-2010 The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira Shannon Victoria Stevens University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Repository Citation Stevens, Shannon Victoria, "The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira" (2010). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 371. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1606942 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RHETORICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF GOJIRA by Shannon Victoria Stevens Bachelor of Arts Moravian College and Theological Seminary 1993 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Communication Studies Department of Communication Studies Greenspun College of Urban Affairs Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2010 Copyright by Shannon Victoria Stevens 2010 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE COLLEGE We recommend the thesis prepared under our supervision by Shannon Victoria Stevens entitled The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Studies David Henry, Committee Chair Tara Emmers-Sommer, Committee Co-chair Donovan Conley, Committee Member David Schmoeller, Graduate Faculty Representative Ronald Smith, Ph. -

Grades 9-12 Sample High School Fundamentals I Learning Plan Big Idea/ Topic Researching Historical Styles

Grades 9-12 Sample High School Fundamentals I Learning Plan Big Idea/ Topic Researching Historical Styles (This lesson plan along with Lesson plan 4 should be repeated for multiple historical periods) Connecting Theme/Enduring Understanding: The skills associated with auditioning allow students to explore skills similar to presentations in non-theatre related fields. Students will demonstrate an understanding of the process of preparing a performance associated with a particular historical period through research. Essential Questions: How does one research appropriately for a given acting style? What is a period style? How do theatrical traditions connect to specific societal, cultural, and historical contexts? Standard Alignment PERFORMING TAHSFT.PR.1 Act by communicating and sustaining roles in formal and informal environments. c. Explore various acting methods and techniques (e.g. Stanislavski, Uta Hagen, sense memory, emotional recall) for the purpose of character development. d. Perform acting choices for an audience based on critiques. RESPONDING TAHSFT.RE.1 Engage actively and appropriately as an audience member. b. State and support aesthetic judgments through experience in diverse styles and genres of theatre. TAHSFT.RE.2 Critique various aspects of theatre and other media using appropriate supporting evidence. a. Generate and use the terminology for critiquing theatre presentations. b. Analyze performance and utilize various effective forms of criticism to respond to and/or improve performance. CONNECTING TAHSFT.CN.1 Explore how theatre connects to life experiences, careers, and other Content d. Explore various careers in the theatre arts (e.g. performance, design, production, administrative, education, promotion). TAHSFT.CN.2 Examine the role of theatre in a societal, cultural, and historical context. -

A Thesis Entitled Yoshimoto Taka'aki, Communal Illusion, and The

A Thesis entitled Yoshimoto Taka’aki, Communal Illusion, and the Japanese New Left by Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for requirements for The Master of Arts Degree in History ________________________ Adviser: Dr. William D. Hoover ________________________ Adviser: Dr. Peter Linebaugh ________________________ Dr. Alfred Cave ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo (July 2005) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is customary in a note of acknowledgments to make the usual mea culpa concerning the impossibility of enumerating all the people to whom the author has incurred a debt in writing his or her work, but, in my case, this is far truer than I can ever say. This note is, therefore, a necessarily abbreviated one and I ask for a small jubilee, cancellation of all debts, from those that I fail to mention here due to lack of space and invidiously ungrateful forgetfulness. Prof. Peter Linebaugh, sage of the trans-Atlantic commons, who, as peerless mentor and comrade, kept me on the straight and narrow with infinite "grandmotherly kindness" when my temptation was always to break the keisaku and wander off into apostate digressions; conversations with him never failed to recharge the fiery voltage of necessity and desire of historical imagination in my thinking. The generously patient and supportive free rein that Prof. William D. Hoover, the co-chair of my thesis committee, gave me in exploring subjects and interests of my liking at my own preferred pace were nothing short of an ideal that all academic apprentices would find exceedingly enviable; his meticulous comments have time and again mercifully saved me from committing a number of elementary factual and stylistic errors. -

Download the Program (PDF)

ヴ ィ ボー ・ ア ニ メー シ カ ョ ワ ン イ フ イ ェ と ス エ ピ テ ッ ィ Viborg クー バ AnimAtion FestivAl ル Kawaii & epikku 25.09.2017 - 01.10.2017 summAry 目次 5 welcome to VAF 2017 6 DenmArk meets JApAn! 34 progrAmme 8 eVents Films For chilDren 40 kAwAii & epikku 8 AnD families Viborg mAngA AnD Anime museum 40 JApAnese Films 12 open workshop: origAmi 42 internAtionAl Films lecture by hAns DybkJær About 12 important ticket information origAmi 43 speciAl progrAmmes Fotorama: 13 origAmi - creAte your own VAF Dog! 44 short Films • It is only possible to order tickets for the VAF screenings via the website 15 eVents At Viborg librAry www.fotorama.dk. 46 • In order to pick up a ticket at the Fotorama ticket booth, a prior reservation Films For ADults must be made. 16 VimApp - light up Viborg! • It is only possible to pick up a reserved ticket on the actual day the movie is 46 JApAnese Films screened. 18 solAr Walk • A reserved ticket must be picked up 20 minutes before the movie starts at 50 speciAl progrAmmes the latest. If not picked up 20 minutes before the start of the movie, your 20 immersion gAme expo ticket order will be annulled. Therefore, we recommended that you arrive at 51 JApAnese short Films the movie theater in good time. 22 expAnDeD AnimAtion • There is a reservation fee of 5 kr. per order. 52 JApAnese short Film progrAmmes • If you do not wish to pay a reservation fee, report to the ticket booth 1 24 mAngA Artist bAttle hour before your desired movie starts and receive tickets (IF there are any 56 internAtionAl Films text authors available.) VAF sum up: exhibitions in Jane Lyngbye Hvid Jensen • If you wish to see a movie that is fully booked, please contact the Fotorama 25 57 Katrine P. -

From 'Scottish' Play to Japanese Film: Kurosawa's Throne of Blood

arts Article From ‘Scottish’ Play to Japanese Film: Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood Dolores P. Martinez Emeritus Reader, SOAS, University of London, London WC1H 0XG, UK; [email protected] Received: 16 May 2018; Accepted: 6 September 2018; Published: 10 September 2018 Abstract: Shakespeare’s plays have become the subject of filmic remakes, as well as the source for others’ plot lines. This transfer of Shakespeare’s plays to film presents a challenge to filmmakers’ auterial ingenuity: Is a film director more challenged when producing a Shakespearean play than the stage director? Does having auterial ingenuity imply that the film-maker is somehow freer than the director of a play to change a Shakespearean text? Does this allow for the language of the plays to be changed—not just translated from English to Japanese, for example, but to be updated, edited, abridged, ignored for a large part? For some scholars, this last is more expropriation than pure Shakespeare on screen and under this category we might find Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (Kumonosu-jo¯ 1957), the subject of this essay. Here, I explore how this difficult tale was translated into a Japanese context, a society mistakenly assumed to be free of Christian notions of guilt, through the transcultural move of referring to Noh theatre, aligning the story with these Buddhist morality plays. In this manner Kurosawa found a point of commonality between Japan and the West when it came to stories of violence, guilt, and the problem of redemption. Keywords: Shakespeare; Kurosawa; Macbeth; films; translation; transcultural; Noh; tragedy; fate; guilt 1. -

Hayao Miyazaki Film

A HAYAO MIYAZAKI FILM ORIGINAL STORY AND SCREENPLAY WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY HAYAO MIYAZAKI MUSIC BY JOE HISAISHI THEME SONGS PERFORMED BY MASAKO HAYASHI AND FUJIOKA FUJIMAKI & NOZOMI OHASHI STUDIO GHIBLI NIPPON TELEVISION NETWORK DENTSU HAKUHODO DYMP WALT DISNEY STUDIOS HOME ENTERTAINMENT MITSUBISHI AND TOHO PRESENT A STUDIO GHIBLI PRODUCTION - PONYO ON THE CLIFF BY THE SEA EXECUTIVE PRODUCER KOJI HOSHINO PRODUCED BY TOSHIO SUZUKI © 2008 Nibariki - GNDHDDT Studio Ghibli, Nippon Television Network, Dentsu, Hakuhodo DYMP, Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, Mitsubishi and Toho PRESENT PONYO ON THE CLIFF BY THE SEA WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY HAYAO MIYAZAKI Running time: 1H41 – Format: 1.85:1 Sound: Dolby Digital Surround EX - DTS-ES (6.1ch) INTERNATIONAL PRESS THE PR CONTACT [email protected] Phil Symes TEL 39 346 336 3406 Ronaldo Mourao TEL +39 346 336 3407 WORLD SALES wild bunch Vincent Maraval TEL +33 6 11 91 23 93 E [email protected] Gaël Nouaille TEL +33 6 21 23 04 72 E [email protected] Carole Baraton / Laurent Baudens TEL +33 6 70 79 05 17 E [email protected] Silvia Simonutti TEL +33 6 20 74 95 08 E [email protected] PARIS OFFICE 99 Rue de la Verrerie - 75004 Paris - France TEL +33 1 53 01 50 30 FAX +33 1 53 01 50 49 [email protected] PLEASE NOTE: High definition images can be downloaded from the ‘press’ section of http://www.wildbunch.biz SYNOPSIS CAST A small town by the sea. Lisa Tomoko Yamaguchi Koichi Kazushige Nagashima Five year-old Sosuke lives high on a cliff overlooking Gran Mamare Yuki Amami the Inland Sea.