Grupo Clarín S.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informe Final Manco Perez

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasd fghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx INFORME FINAL DE cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqPROYECTO DE INVESTIGACIÓN wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui Directora: Gloria Hintze Becaria: Ana Cecilia Manco Pérez opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg Abril de 2012 hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc Aval Académico - CIC Facultad de Ciencias P olíticas y Sociales. UNCuyo vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmrtyuiopa sdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz 2 FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS Y SOCIALES PROGRAMA DE BECAS PARA LA FORMACIÓN DE INVESTIGADORES CONVOCATORIA 2011-2012 Mi experiencia como becaria, con Aval Académico, del Centro de Investigaciones de nuestra Facultad, ha sido beneficiosa para mi formación como investigadora y docente en educación secundaria. Durante este tiempo, pude darme cuenta de lo apasionante que puede ser la ciencia en términos reflexivos y relacionales. Esto significa, pasar del plano de la observación, dejar de contemplar la realidad para tomar una conciencia crítica de la ciencia; una cultura de formación, que te permite dar forma y comprender el entorno a partir de la elaboración de una teoría. Ésta a su vez, es un pensamiento relacional con realidad ontológica que expresan cómo -

Trabajo Fin De Grado

Trabajo Fin de Grado Periodismo militante en Argentina Estudio de caso: Seis en el siete a las ocho (Televisión pública) y Periodismo para todos (Televisión privada) Autora Bárbara Solange Bufi Directora María Angulo Egea Facultad de Filosofía y Letras 2012-2013 Índice RESUMEN ................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introducción ........................................................................................................... 4 2. Metodología ........................................................................................................... 5 3. Marco teórico y contexto histórico ......................................................................... 6 3.1 Fórmulas de populismo y los orígenes del kirchnerismo ................................... 6 3.2 Eva y Cristina, mujeres de armas tomar ............................................................ 7 3.3 Peronismo, kirchnerismo y medios de comunicación ...................................... 10 4. Periodismo militante y periodismo independiente ................................................ 11 5. Formatos televisivos actuales: militancia e independencia....................................... 13 5.1 Seis en el siete a las ocho (6,7,8) .................................................................... 15 5.2 Periodismo para todos (PPT) .......................................................................... 25 6. Seis en el siete a las ocho vs. Periodismo para todos ............................................... -

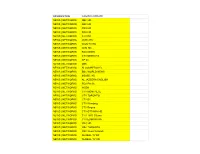

Listado De Canales Tv Prime Plus

Listado de Canales Tv Prime Plus ARGENTINA AR | TELEFE *FHD BR | TELECINE CULT *HD BR | DISNEY JUNIOR *HD CA | PBS Buffalo (WNED) AR | AMERICA 24 *FHD AR | TELEFE *HD BR | TELECINE ACTION *HD BR | DISNEY CHANNEL *HD CA | OWN AR | AMERICA 24 *HD AR | TELEFE *HD BR | TCM *HD BR | DISCOVERY WORLD *HD CA | OMNI_2 AR | AMERICA TV *FHD AR | TELEMAX *HD BR | TBS *HD BR | DISCOVERY TURBO *HD CA | OMNI_1 AR | AMERICA TV *HD AR | TELESUR *HD BR | SYFY *HD BR | DISCOVERY THEATHER *HD CA | OLN AR | AMERICA TV *HD | op2 AR | TN *HD BR | STUDIO UNIVERSAL *HD BR | DISCOVERY SCIENCE *HD CA | CablePulse 24 AR | C5N *HD AR | TV PUBLICA *FHD BR | SPACE *HD BR | DISCOVERY KIDS *HD CA | NBA_TV AR | C5N *HD | op2 AR | TV PUBLICA *HD BR | SONY *HD BR | DISCOVERY ID *HD CA | NAT_GEO AR | CANAL 21 *HD AR | TV PUBLICA *HD | op2 BR | REDE VIDA *HD BR | DISCOVERY H&H *HD CA | MUCH_MUSIC AR | CANAL 26 *HD AR | TV5 *HD BR | REDE TV *HD BR | DISCOVERY CIVILIZATION *HD CA | MTV AR | CANAL 26 NOTICIAS *HD AR | TVE *HD BR | REDE BRASIL *HD BR | DISCOVERY CH. *HD CA | Makeful AR | CANAL 26 NOTICIAS *HD AR | VOLVER *HD BR | RECORD NEWS *HD BR | COMEDY CENTRAL *HD CA | HLN AR | CANAL DE LA CIUDAD *HD BR | RECORD *HD BR | COMBATE *HD CA | History Channel AR | CANAL DE LA MUSICA *HD BOLIVIA BR | PLAY TV *HD BR | CINEMAX *HD CA | GOLF AR | CINE AR *HD BO | ATB BR | PARAMOUNT *HD BR | CARTOON NETWORK *HD CA | Global Toronto (CIII) AR | CINE AR *HD BO | BOLIVIA TV BR | NICKELODEON *HD BR | CANAL BRASIL *HD CA | Game TV AR | CIUDAD MAGAZINE *HD BO | BOLIVISION *HD BR | NICK JR -

Copyright by Elizabeth Ann Maclean 2014

Copyright by Elizabeth Ann MacLean 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Elizabeth Ann MacLean Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “Not Your Abuela’s Telenovela: Mujeres Asesinas As a Hybrid Latin American Fiction Format” Committee: Joseph D. Straubhaar, Supervisor América Rodríguez Charles Ramírez Berg Shanti Kumar Viviana Rojas “Not Your Abuela’s Telenovela: Mujeres Asesinas As a Hybrid Latin American Fiction Format” by Elizabeth Ann MacLean, B.F.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2014 Dedication To Alejandro, Diego, mom and dad, with all my love and gratitude. Acknowledgements Over my time at The University of Texas at Austin, I have received support and encouragement from a great number of individuals. Dr. Joseph D. Straubhaar has been not only a mentor, but also a colleague and a friend. His teaching and guidance pointed the way and made my journey through graduate school that much more rewarding. I would also like to thank my committee members, Drs. Charles Ramírez Berg, Shanti Kumar, Viviana Rojas and América Rodríguez who so kindly and patiently shared their knowledge and provided important insights as I moved from an idea to a proposal, and then to a completed study. I am grateful for the support of the National Association of Television Executives, NATPE, and Dr. Gregg Pitts, who provided an invaluable opportunity to learn about international television markets on site, in Miami. -

The Crisis of Journalism and State Retraction Policies in Argentina, Brazil and Chile

The crisis of journalism and state retraction policies in DANIELA INÉS MONJE1 Argentina, Brazil and Chile https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4579-855X Crisis del periodismo y EZEQUIEL ALEXANDER RIVERO2 políticas de retracción de los estados http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8124-0975 en Argentina, Brasil y Chile JUAN MARTÍN ZANOTTI3 DOI: https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2020.7491 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9871-0515 This article aims to study how the ownership structure of the media system and the role of the State are linked to the deterioration of journalistic work and the exercise of freedom of expression. From the Political Economy of Journalism and the discussions on the right to information, a comparative study is proposed to contrast the situation in Brazil, Argentina and Chile between 2016 and 2018. It is concluded that the high concentration in the three media systems, along with the retraction of the State as regulator and content producer, deepen a crisis that threatens journalistic activity. KEYWORDS: Journalism, Political economy, Freedom of Expression, Crisis, Media concentration. Este artículo analiza cómo la estructura de propiedad del sistema mediático y el rol del Estado, se vinculan con el deterioro del trabajo periodístico y el ejercicio de la libertad de expresión. Desde la Economía Política del Periodismo y las discusiones sobre el derecho a la información, el estudio comparativo propuesto contrasta la situación en Brasil, Argentina y Chile entre 2016 y 2018. Se concluye que la alta concentración en los tres sistemas de medios, junto a la retracción del Estado como regulador y productor de contenidos, profundizan una crisis que amenaza la actividad periodística. -

Channels List

INFORMATION COVID19 UPDATE NEWS | NETWORKS NBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS ABC HD NEWS | NETWORKS CBS HD NEWS | NETWORKS FOX HD NEWS | NETWORKS CTV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CNBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS WGN TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CNN HD NEWS | NETWORKS FOX NEWS NEWS | NETWORKS CTV NEWS HD NEWS | NETWORKS CP 24 NEWS | NETWORKS BNN NEWS | NETWORKS BLOOMBERG HD NEWS | NETWORKS BBC WORLD NEWS NEWS | NETWORKS MSNBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS AL JAZEERA ENGLISH NEWS | NETWORKS FOX Pacific NEWS | NETWORKS WSBK NEWS | NETWORKS CTV MONTREAL NEWS | NETWORKS CTV TORONTO NEWS | NETWORKS CTV BC NEWS | NETWORKS CTV Winnipeg NEWS | NETWORKS CTV Regina NEWS | NETWORKS CTV OTTAWA HD NEWS | NETWORKS CTV TWO Ottawa NEWS | NETWORKS CTV EDMONTON NEWS | NETWORKS CBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS CBC TORONTO NEWS | NETWORKS CBC News Network NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV BC NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV CALGARY NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV MONTREAL NEWS | NETWORKS CITY TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CITY VANCOUVER NEWS | NETWORKS WBTS NEWS | NETWORKS WFXT NEWS | NETWORKS WEATHER CHANNEL USA NEWS | NETWORKS MY 9 HD NEWS | NETWORKS WNET HD NEWS | NETWORKS WLIW HD NEWS | NETWORKS CHCH NEWS | NETWORKS OMNI 1 NEWS | NETWORKS OMNI 2 NEWS | NETWORKS THE WEATHER NETWORK NEWS | NETWORKS FOX BUSINESS NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 10 Miami NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 10 San Diego NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 12 San Antonio NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 13 HOUSTON NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 2 ATLANTA NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 4 SEATTLE NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 5 CLEVELAND NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 9 ORANDO HD NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 6 INDIANAPOLIS HD NEWS | NETWORKS -

Grupo Perfil Tendrá Dos Nuevas Señales, Alfa Y Bravo TV

Grupo Perfil tendrá dos nuevas señales, Alfa y Bravo TV Junto a Net TV suman tres los nuevos canales de televisión de aire, género distinto a las señales de cable que son monotemáticas. Por Jorge Fontevecchia, cofundador de Editorial Perfil y CEO de Perfil Network Acaban de cumplirse dos años del lanzamiento de NET TV, el primer nuevo canal de televisión de aire después de medio siglo: ese mismo día –1° de octubre– El Trece cumplió 60 años. Todos los demás canales de televisión abierta nacieron en la misma época, Canal 9 también cumple 60 años, Telefe cumple 30 años con ese nombre pero 59 años como Canal 11, y América TV, 54 años. NET TV es del Grupo Perfil en sociedad con la mayor y más exitosa productora de televisión abierta de la Argentina: Kuarzo, ex Endemol, conducida por quien acumula más horas de experiencia en producción de programas de televisión en la Argentina, Martín Kweller, introductor de los realities en el país a partir de la saga de Gran Hermano y con programas en todos los canales de televisión. En Telefe: PH con Andy Kusnetzoff y Cortá por Lozano con Verónica Lozano. En El Trece: Bienvenidos a bordo con Guido Kaczka y Nosotros a la mañana. En Canal 9: El show del problema y Todo puede pasar. En América TV: Polémica en el bar. Más todos los programas no periodísticos de NET TV: Pampita online, Como todo y Editando tele. En estos dos años de vida NET TV duplicó el rating con que comenzó y aunque aún está lejos de los canales de televisión abierta comerciales, llegó a superar en rating a la TV Pública durante el prime time y se prepara para seguir creciendo. -

Descargar Informe

Nuevo Informe TOP Julio 2012 TOP presenta el nuevo informe sobre Consumo, Coyuntura Nacional y Medios. Te acercamos un pequeño avance. Para ver el informe completo ingresá a www.termometrotop.com.ar Además, visitá la sección Desk Research donde encontrarás nuevas investigaciones sobre tendencias. CIENCIA PARA TODOS • Tras la reapertura de Tecnópolis, te contamos cuantos de nuestros entrevistados planean asistir al parque temático este año. LONDRES 2012 • Comenzaron los Juegos Olímpicos y algunos piensan en cambiar su televisión para no perderse de ningún detalle. Te mostramos cuantos de nuestros entrevistados optan por renovar su pantalla. SUBE • A partir del 6 de agosto quienes no utilicen el sistema SUBE deben pagar sus viajes sin subsidio. Ante esto, surge una pregunta inevitable: ¿qué nivel de satisfacción tiene la tarjeta entre los usuarios? ¿NO VA MÁS? • Desde hace unos meses, el Gobierno Nacional y Hugo Moyano, líder de la CGT, están enfrentados. ¿Cómo ven esta situación Contacto [email protected] o [email protected] nuestros entrevistados? ¿Es una ruptura definitiva o todavía es posible una reconciliación? AZULES • Restricciones y dólar blue, temas presentes en las conversaciones de los argentinos desde que se anunció la medida. Te contamos cómo ven nuestros entrevistados las restricciones para la compra/ venta de dólares. MEDIO Y MEDIO • Los empleados públicos de la Provincia de Buenos Aires cobraron su aguinaldo en dos cuotas, debido al déficit fiscal que vive el distrito. Más allá de los pases de facturas entre Provincia y Nación, ¿quién es responsable por el desdoblamiento del pago? AFUERA • Cavenaghi y Alejandro “Chori” Domínguez se fueron de River, ¿cómo ven su salida nuestros entrevistados? LANATA • En abril, Jorge Lanata volvió a la televisión con PPT (Periodismo para todos), en la pantalla de El Trece, y en estos meses ya generó varios debates. -

Standing Committee on Copyright and Related Rights

E SCCR/30/5 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH DATE: JUNE 2, 2015 Standing Committee on Copyright and Related Rights Thirtieth Session Geneva, June 29 to July 3, 2015 CURRENT MARKET AND TECHNOLOGY TRENDS IN THE BROADCASTING SECTOR prepared by IHS Technology IHS TECHNOLOGY Current Market and Technology Trends in the Broadcasting Sector May 2015 ihs.com Introduction Like so many facets of the modern world, television has been transformed by the application of digital technologies and the parallel and related development of the fast evolving Internet. While some broadcasters – especially those in developing economies - still utilise traditional analogue transmission techniques, most have transitioned to more efficient and powerful digital means of sending their programming to viewers. Use of digital technologies has enabled explosive growth in the number of channels and choices of programmes offered. It has also ceded more control to the viewer, allowing on-demand access to programming – not only from broadcasters and pay TV service providers, but also increasingly from online video services delivered over the open Internet. Indeed, as this report outlines, the definitional boundaries between broadcasting and other forms of digital video delivery are increasingly blurred. The viewer is undoubtedly a winner as a result of these developments as we move ever closer to the ultimate provision of ubiquitous choice, convenience and control. And broadcasters are usually winners too as evidenced by the impressive global TV market growth described in this report. Inevitably, that growth and technological development is not evenly distributed geographically, and we outline some of the key regional trends in the pages that follow, as well as some more focused snapshots of the market evolution within selected countries. -

Lista De Canales Megatv

PaÍses/ Clasificación Canales MAX PRIME HD FOX FAMILY HD HBO PLUS OESTE MULTICINEMA HD FX MOVIES OESTE CINEMAX OESTE MAX HD FOX SERIES OESTE HBO PLUS ESTE MAX UP HD FX MOVIES CINEMAX FOX SERIES MAX HD (SAP) HBO PLUS PANICO HD FX MOVIES HD MAX PRIME ESTE FOX SERIES HD FOX COMEDY HBO SIGNATURE GOLDEN HD FOX ACTION FX HD CINECANAL (PANREGIONAL) FOX COMEDY HD HBO FAMILY DE PELICULA FOX ACTION HD MAX PRIME OESTE PELÍCULAS CINECANAL FOX CINEMA HBO 2 (PANAMERICANA) STUDIO UNIVERSAL FOX MOVIES MAX PRIME CINECANAL HD HBO FAMILY HD HBO 2 UNIVERSAL FOX MOVIES HD DHE HD CINEMA DINAMITA FOX CINEMA HD HBO OESTE SPACE (PANAMERICANO) FOX CLASSICS MAX (PANAMERICANO) CINE LATINO HBO 2 HD HBO ESTE SPACE HD FOX CLASSICS HD CHOCHO HD GOLDEN EDGE (PANREGIONAL) HBO HD PARAMOUNT CHANNEL FOX FAMILY OESTE MULTIPREMIER GOLDEN HBO SIGNATURE HD PARAMOUNT HD FOX FAMILY TNT SPORTS GOL PERU FIGHTING SPORTS NETWORK HD ESPN BR HD CABLE ONDA SPORTS FC HD LIGA BOLIVIA HD GOL TV NBC SPORTS NETWORK ESPN BRASIL ESPN 2 HD (NORTE) FOX SPORTS PREMIUM (ARGENTINA) TYC SPORTS HD TENNIS CHANNEL HD ESPN BRASIL HD CABLE ONDA SPORTS HD COMBATE HD FOX SPORTS BR FOX SPORTS 2 HD (NORTE) FOX SPORTS 3 (SUR) ESPN (SUR) NBA TV FOX SPORTS HD BR CBS SOPRTS NETWORK FOX SPORTS 3 HD (SUR) ESPN HD (SUR) ESPN 3 (SUR) UNIVISION DEPORTES HD FOX SPORTS (CONO SUR) FOX SPORTS 3 HD (NORTE) ESPN (NORTE) ESPN 3 (NORTE) TNT SPORTS HD FOX SPORTS 1 (SUR) FOX SPORTS 2 (SUR) ESPN HD (NORTE) DEPORTE ESPN 2 (SUR) TYC SPORTS FOX SPORTS 1 HD (CHILE) FOX SPORTS 2 HD (SUR) ESPN+HD CLARO SPORT CDF BASICO FOX SPORTS 1 -

La Televisión Abierta Argentina En El Escenario Digital* Argentinian Open Television in the Digital Scenery a Televisão Aberta Argentina No Palco Digital

Artículos La televisión abierta argentina en el escenario digital* Argentinian Open Television in the Digital Scenery A televisão aberta argentina no palco digital Ornela Vanina Carboni a DOI: https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.syp39.taae Universidad Nacional de Quilmes, Argentina [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3968-6455 Recibido: 25 Marzo 2018 Aceptado: 16 Abril 2019 Publicado: 24 Junio 2020 Resumen: Los procesos de digitalización y convergencia tecnológica representan un desafío para los medios de comunicación en el siglo XXI. La tradicional industria televisiva debió adaptar la distribución de contenidos audiovisuales a través de diversas pantallas. Este artículo intenta sistematizar la implementación de la televisión abierta en Internet en Argentina. El estudio abarca desde la aparición de los sitios web de las emisoras televisivas hasta el 2017, es decir, a partir de la presencia corporativa de los canales hasta el desarrollo de contenidos ad hoc para la web y/o aplicaciones móviles y el uso de las redes sociales. Especícamente, el trabajo se centra en los casos de El Trece (Canal 13), Telefe (Canal 11) y la Televisión Pública (Canal 7). De este modo, el estudio de carácter descriptivo y exploratorio observa la distribución de los contenidos a través de Internet por parte de las emisoras televisivas en abierto de Argentina y su adaptación al ecosistema mediático digital con la aparición de competidores emergentes del universo online. El diseño metodológico de tipo cualitativo analiza la distribución de contenidos audiovisuales en la red por parte de las emisoras televisivas en abierto de Argentina (El Trece, Telefe y TV Pública), para ello se procedió a la revisión bibliográca y a la realización de entrevistas a los responsables de las áreas digitales. -

Canal Institucional *Hq Co | Canal Trece *Hd Co

CO | CABLE NOTICIAS *HD CL | CANAL 13 *FHD | Directo AR | AMERICA TV *HD | op2 AR | SENADO *HD CO | CANAL CAPITAL *HD CL | CANAL 13 CABLE *HD AR | C5N *HD AR | TELEFE *FHD CO | CANAL INSTITUCIONAL *HQ CL | CANAL 13 AR | C5N *HD | op2 AR | TELEFE *HD CO | CANAL TRECE *HD INTERNACIONACIONAL *HD AR | CANAL 21 *HD AR | TELEFE *HD CO | CANAL UNO *HD CL | CHV *HQ AR | CANAL 26 *HD AR | TELEMAX *HD CO | CANTINAZO *HD CL | CHV *HD AR | CANAL 26 NOTICIAS *HD AR | TELESUR *HD CO | CARACOL *HQ CL | CHV *FHD AR | CANAL 26 NOTICIAS *HD AR | TN *HD CO | CARACOL *HD CL | CHV *FHD | Directo AR | CANAL DE LA CIUDAD *HD AR | TV PUBLICA *FHD CO | CARACOL *FHD CL | LA RED *HQ AR | CANAL DE LA MUSICA *HD AR | TV PUBLICA *HD CO | CARACOL 2 *FHD CL | LA RED *HD AR | CINE AR *HD AR | TV PUBLICA *HD | op2 CO | CARACOL INTERNACIONAL *HD CL | LA RED *FHD AR | CINE AR *HD AR | TV5 *HD CO | CITY TV *HD CL | LA RED *FHD | Directo AR | CIUDAD MAGAZINE *HD AR | TVE *HD CO | COSMOVISION *HD CL | MEGA *HQ AR | CN23 *HD AR | VOLVER *HD CO | EL TIEMPO *HD CL | MEGA *HD AR | CN23 *HD AR | TELEFE INTERNACIONAL *HD CO | LA KALLE *HD CL | MEGA *FHD AR | CONEXION *HD A&E *FHD CO | NTN24 *HD CL | MEGA *HD | Op2 AR | CONSTRUIR *HD A3 SERIES *FHD CO | RCN *HQ CL | MEGA *FHD | Directo AR | CRONICA *HD AMC *FHD CO | RCN *HD CL | MEGA PLUS *FHD AR | CRONICA *HD ANTENA 3 *FHD CO | RCN *FHD CL | TVN *HQ AR | DEPORTV *HD AXN *FHD CO | RCN 2 *FHD CL | TVN *HD AR | EL NUEVE *HD CINECANAL *FHD CO | RCN NOVELAS *HD CL | TVN *FHD AR | EL NUEVE *FHD CINEMAX *FHD CO | RCN INTERNACIONAL CL |