An Interview with Jonathan Zalben

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMS/SMT Indianapolis 2010: Abstracts

AMS_2010_full.pdf 1 9/11/2010 5:08:41 PM ASHGATE New Music Titles from Ashgate Publishing… Adrian Willaert and the Theory Music, Sound, and Silence of Interval Affect in Buffy the Vampire Slayer The Musica nova Madrigals and the Edited by Paul Attinello, Janet K. Halfyard Novel Theories of Zarlino and Vicentino and Vanessa Knights Timothy R. McKinney Ashgate Popular and Folk Music Series Includes 69 music examples Includes 20 b&w illustrations Aug 2010. 336 pgs. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6509-0 Feb 2010. 304 pgs. Pbk. 978-0-7546-6042-2 Changing the System: The Musical Ear: The Music of Christian Wolff Oral Tradition in the USA Edited by Stephen Chase and Philip Thomas Anne Dhu McLucas Includes 1 b&w illustration and 49 musical examples SEMPRE Studies in The Psychology of Music Aug 2010. 284 pgs. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6680-6 Includes 1 b&w illustration, 2 music examples and a CD Mar 2010. 218 pgs. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6396-6 Shostakovich in Dialogue Form, Imagery and Ideas in Quartets 1–7 Music and the Modern Judith Kuhn Condition: Investigating Includes 32 b&w illustrations and 99 musical examples Feb 2010. 314 pgs. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6406-2 the Boundaries Ljubica Ilic Harrison Birtwistle: Oct 2010. 140 pgs. Hbk. 978-1-4094-0761-4 C The Mask of Orpheus New Perspectives M Jonathan Cross Landmarks in Music Since 1950 on Marc-Antoine Charpentier Includes 10 b&w illustrations and 12 music examples Edited by Shirley Thompson Y Dec 2009. 196 pgs. Hbk. 978-0-7546-5383-7 Includes 2 color and 20 b&w illustrations and 37 music examples Apr 2010. -

2004 Annual Report

2004 Annual Report Mission Statement Remembering Balanchine Peter Martins - Ballet Master in Chief Meeting the Demands Barry S. Friedberg - Chairman New York City Ballet Artistic NYCB Orchestra Board of Directors Advisory Board Balanchine 100: The Centennial Celebration 2003-2004 The Centennial Celebration Commences & Bringing Balanchine Back-Return to Russia On to Copenhagen & Winter Season-Heritage A Warm Welcome in the Nation's Capital & Spring Season-Vision Exhibitions, Publications, Films, and Lectures New York City Ballet Archive New York Choreographic Institute Education and Outreach Reaching New Audiences through Expanded Internet Technology & Salute to Our Volunteers The Campaign for New York City Ballet Statements of Financial Position Statements of Activities Statements of Cash Flows Footnotes Independent Auditors' Report All photographs by © Paul Kolnik unless otherwise indicated. The photographs in this annual report depict choreography copyrighted by the choreographer. Use of this annual report does not convey the right to reproduce the choreography, sets or costumes depicted herein. Inquiries regarding the choreography of George Balanchine shall be made to: The George Balanchine Trust 20 Lincoln Center New York, NY 10023 Mission Statement George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein formed New York City Ballet with the goal of producing and performing a new ballet repertory that would reimagine the principles of classical dance. Under the leadership of Ballet Master in Chief Peter Martins, the Company remains dedicated to their vision as it pursues two primary objectives: 1. to preserve the ballets, dance aesthetic, and standards of excellence created and established by its founders; and 2. to develop new work that draws on the creative talents of contemporary choreographers and composers, and speaks to the time in which it is made. -

Spoleto Festival Usa Program History 2016 – 1977

SPOLETO FESTIVAL USA PROGRAM HISTORY 2016 – 1977 Spoleto Festival USA Program History Page 2 2016 Opera Porgy and Bess; created by George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin; conductor, Stefan Asbury; director, David Herskovits; visual designer, Jonathan Green; lighting designer, Lenore Doxsee; wig and makeup designer, Ruth Mitchell; set designer, Carolyn Mraz; costume designer, Annie Simon; fight director, Brad Lemons; Cast: Alyson Cambridge, Lisa Daltirus, Eric Greene, Courtney Johnson, Lester Lynch, Sidney Outlaw, Victor Ryan Robertson, Indra Thomas; Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra, Johnson C. Smith University Concert Choir; Charleston Gaillard Center *La Double Coquette; music by Antoine Dauvergne with additions by Gérard Pesson; libretto by Charles-Simon Favart with additions by Pierre Alferi; director, Fanny de Chaillé; costume designer, Annette Messager; costume realization, Sonia de Sousa; lighting designer, Gilles Gentner; lighting realization, Cyrille Siffer; technical stage coordination, Francois Couderd; Cast: Robert Getchell, Isabelle Poulenard, Mailys de Villoutreys; Dock Street Theatre *The Little Match Girl; music and libretto by Helmut Lachenmann; conductor, John Kennedy; co-directors, Mark Down and Phelim McDermott; costume designer, Kate Fry; lighting designer, James F. Ingalls; set designer, Matt Saunders; puppet co-designers, Fiona Clift, Mark Down, Ruth Patton; Cast: Heather Buck, Yuko Kakuta, Adam Klein; Soloists: Chen Bo, Stephen Drury, Renate Rohlfing, Memminger Auditorium Dance Bill T. Jones/Arnie -

Gp 3.Qxt 7/14/17 12:16 PM Page 1

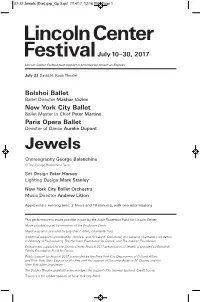

07-22 Jewels (Eve).qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/14/17 12:16 PM Page 1 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 22 David H. Koch Theater Bolshoi Ballet Ballet Director Makhar Vaziev New York City Ballet Ballet Master in Chief Peter Martins Paris Opera Ballet Director of Dance Aurélie Dupont Jewels Choreography George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust Set Design Peter Harvey Lighting Design Mark Stanley New York City Ballet Orchestra Music Director Andrew Litton Approximate running time: 2 hours and 10 minutes, with two intermissions This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Made possible in part by members of the Producers Circle Major support is provided by LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust. Additional support is provided by Jennie L. and Richard K. DeScherer, the Lepercq Charitable Foundation in Memory of Paul Lepercq, The Harkness Foundation for Dance, and The Joelson Foundation. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2017 presentation of Jewels is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. Public support for Festival 2017 is provided by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. The Bolshoi Theatre gratefully acknowledges the support of its General Sponsor, Credit Suisse. Travelers is the Global Sponsor of New York City Ballet. 07-22 Jewels (Eve).qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/14/17 12:16 PM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2017 JEWELS July 22, 2017, at 7:30 p.m. -

Download the Entire Issue (PDF)

AMERICAN MUSIC REVIEW THE HITCHCOCK INSTITUTE FOR STUDIES IN AMERICAN MUSIC Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York VOLUME L, ISSUE 2 SPRING 2021 Cecil Taylor’s Posthumanistic Musical Score Jessie Cox “He would play the line, and we would repeat it. That way we got a more natural feeling for the tune and we got to understand what Cecil wanted.”1 Archie Shepp’s recount of working with Cecil Taylor in 1959 sparked my inquiry into Taylor’s use of musical scores. The music exists, it is written, not on a sheet of paper that is handed to the interpreter, but as a score that is communicated through Taylor demonstrating the piece on the piano.2 I will read this practice of musical scoring alongside Taylor’s own writing; specifically, “Sound Structure of Subculture Becoming Major Breath/Naked Fire Gesture,” the liner notes to the record Unit Structures.3 These scores, which are taught via playing the music for the interpreters, are aura-visual as well as embodied through/in the act of piano playing. Taylor writes that “Western notation” is a “blocking” of “total absorption in the ‘action’ playing,”4 where he conceives of “action” as both internal and external—as the interactivity between the musicians.5 I propose to hear this via intra-action6 (Barad’s term for the co-making of differences [subjects/objects, concepts, instruments, etc.]), elaborated via Glissantian créolité,7 which relies on opacity and the unforseeable.8 This approach to composition problematizes the location and function of musical scores and at the same time, of course, also interpretation. -

What Is a Philistine? : Music in the Nineteenth Century

What is a Philistine? : Music in the Nineteenth Century http://www.oxfordwesternmusic.com/view/Volume3/actrade-9780195... Oxford History of Western Music: Richard Taruskin See also from Grove Music Online Hector Berlioz Robert Schumann Schumann: The music critic WHAT IS A PHILISTINE? Chapter: CHAPTER 6 Critics Source: MUSIC IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Author(s): Richard Taruskin fig. 6-1 Robert Schumann, drawing from a daguerreotype by Johann Anton Völlner, Hamburg, March 1850. 1 / 4 2011.01.27. 16:28 What is a Philistine? : Music in the Nineteenth Century http://www.oxfordwesternmusic.com/view/Volume3/actrade-9780195... The Philistines, in history, were a non-Semitic (probably Greek) people who settled on the Mediterranean coast, in a region now named Palestine after them, around 1200 bce. In the Bible, of course, they figure as the historical enemies of the Israelites, God's “chosen people.” It is easy to see how the term could be applied to the opponents of any chosen, or self-chosen, group. In the early nineteenth century the name was applied by artists imbued with the ideals of romanticism to those perceived as their enemies, namely the materialistic, hedonistic “crowd,” indifferent to culture and content with commonplace entertainment. Already a tension within romanticism is exposed, because that crowd, with its “democ ratized” taste, was now the primary source of support for artists, and many romantic artists, notably Liszt, took sustenance from it and actively wooed it. For an idea of romantic ambivalence toward the public, we might recall that it was none other than Liszt who defined for us (in his memoir of John Field, quoted in chapter 2) the romantic ideal of subjective privacy and public indifference.