Download the Entire Issue (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL How to cite: ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL (2021) English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13924/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush’s ‘Workers’ Music’ on 20 th Century Britain’s Left-Wing Music Scene Alice Robinson Abstract Workers’ music: songs to fight injustice, inequality and establish the rights of the working classes. This was a new, radical genre of music which communist composer, Alan Bush, envisioned in 1930s Britain. -

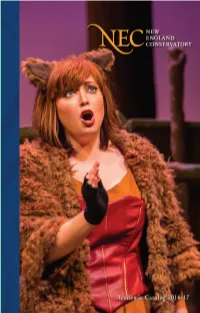

Academiccatalog 2017.Pdf

New England Conservatory Founded 1867 290 Huntington Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 necmusic.edu (617) 585-1100 Office of Admissions (617) 585-1101 Office of the President (617) 585-1200 Office of the Provost (617) 585-1305 Office of Student Services (617) 585-1310 Office of Financial Aid (617) 585-1110 Business Office (617) 585-1220 Fax (617) 262-0500 New England Conservatory is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. New England Conservatory does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, age, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, physical or mental disability, genetic make-up, or veteran status in the administration of its educational policies, admission policies, employment policies, scholarship and loan programs or other Conservatory-sponsored activities. For more information, see the Policy Sections found in the NEC Student Handbook and Employee Handbook. Edited by Suzanne Hegland, June 2016. #e information herein is subject to change and amendment without notice. Table of Contents 2-3 College Administrative Personnel 4-9 College Faculty 10-11 Academic Calendar 13-57 Academic Regulations and Information 59-61 Health Services and Residence Hall Information 63-69 Financial Information 71-85 Undergraduate Programs of Study Bachelor of Music Undergraduate Diploma Undergraduate Minors (Bachelor of Music) 87 Music-in-Education Concentration 89-105 Graduate Programs of Study Master of Music Vocal Pedagogy Concentration Graduate Diploma Professional String Quartet Training Program Professional -

Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 © Copyright by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line by Benjamin Grant Doleac Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Cheryl L. Keyes, Chair The black brass band parade known as the second line has been a staple of New Orleans culture for nearly 150 years. Through more than a century of social, political and demographic upheaval, the second line has persisted as an institution in the city’s black community, with its swinging march beats and emphasis on collective improvisation eventually giving rise to jazz, funk, and a multitude of other popular genres both locally and around the world. More than any other local custom, the second line served as a crucible in which the participatory, syncretic character of black music in New Orleans took shape. While the beat of the second line reverberates far beyond the city limits today, the neighborhoods that provide the parade’s sustenance face grave challenges to their existence. Ten years after Hurricane Katrina tore up the economic and cultural fabric of New Orleans, these largely poor communities are plagued on one side by underfunded schools and internecine violence, and on the other by the rising tide of post-disaster gentrification and the redlining-in- disguise of neoliberal urban policy. -

Pollution and Pandemic

WITHOUT F EAR OR FAVOUR Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXVIII No. 253 | 8 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 31.2 C -0.7 C Monday, November 09, 2020 | 24-07-2077 Biratnagar Jumla As winter sets in, Nepal faces double threat: Pollution and pandemic Studies around the world show the risk of Covid-19 fatality is higher with longer exposure to polluted air which engulfs the country as temperatures plummet. ARJUN POUDEL Kathmandu, relative to other cities in KATHMANDU, NOV 8 respective countries. Prolonged exposure to air pollution Last week, a 15-year-old boy from has been linked to an increased risk of Kathmandu, who was suffering from dying from Covid-19, and for the first Covid-19, was rushed to Bir Hospital, time, a study has estimated the pro- after his condition started deteriorat- portion of deaths from the coronavi- ing. The boy, who was in home isola- rus that could be attributed to the tion after being infected, was first exacerbating effects of air pollution in admitted to the intensive care unit all countries around the world. and later placed on ventilator support. The study, published in “When his condition did not Cardiovascular Research, a journal of improve even after a week on a venti- European Society of Cardiology, esti- lator, we performed an influenza test. mated that about 15 percent of deaths The test came out positive,” Dr Ashesh worldwide from Covid-19 could be Dhungana, a pulmonologist, who is attributed to long-term exposure to air also a critical care physician at Bir pollution. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Download File

NAVIGATING MUSICAL PERIODICITIES: MODES OF PERCEPTION AND TYPES OF TEMPORAL KNOWLEDGE Galen Philip DeGraf Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Galen Philip DeGraf All rights reserved ABSTRACT Navigating Musical Periodicities: Modes of Perception and Types of Temporal Knowledge Galen Philip DeGraf This dissertation explores multi-modal, symbolic, and embodied strategies for navigating musical periodicity, or “meter.” In the first half, I argue that these resources and techniques are often marginalized or sidelined in music theory and psychology on the basis of definition or context, regardless of usefulness. In the second half, I explore how expanded notions of metric experience can enrich musical analysis. I then relate them to existing approaches in music pedagogy. Music theory and music psychology commonly assume experience to be perceptual, music to be a sound object, and perception of music to mean listening. In addition, observable actions of a metaphorical “body” (and, similarly, performers’ perspectives) are often subordinate to internal processes of a metaphorical “mind” (and listeners’ experiences). These general preferences, priorities, and contextual norms have culminated in a model of “attentional entrainment” for meter perception, emerging through work by Mari Riess Jones, Robert Gjerdingen, and Justin London, and drawing upon laboratory experiments in which listeners interact with a novel sound stimulus. I hold that this starting point reflects a desire to focus upon essential and universal aspects of experience, at the expense of other useful resources and strategies (e.g. extensive practice with a particular piece, abstract ideas of what will occur, symbolic cues) Opening discussion of musical periodicity without these restrictions acknowledges experiences beyond attending, beyond listening, and perhaps beyond perceiving. -

Judith Tick. Ruth Crawford Seeger: a Composer's Search for American Music

Document generated on 09/27/2021 2:58 a.m. Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Judith Tick. Ruth Crawford Seeger: A Composer's Search for American Music. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. xiv, 457 pp. ISBN 0-19- 506509-3 (hardcover) Joseph N. Straus. The Music of Ruth Crawford Seeger. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. xii, 260 pp. ISBN 0-521-41646-9 (hardcover) Lori Burns Volume 20, Number 2, 2000 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014470ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1014470ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (print) 2291-2436 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Burns, L. (2000). Review of [Judith Tick. Ruth Crawford Seeger: A Composer's Search for American Music. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. xiv, 457 pp. ISBN 0-19- 506509-3 (hardcover) / Joseph N. Straus. The Music of Ruth Crawford Seeger. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. xii, 260 pp. ISBN 0-521-41646-9 (hardcover)]. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 20(2), 141–147. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014470ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit des universités canadiennes, 2000 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. -

Charles Seeger Musical Compositions and Published Research Articles, 1908-1978

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1j49n5nv No online items Inventory of the Charles Seeger musical compositions and published research articles, 1908-1978 Processed by The Music Library staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Xiuzhi Zhou Music Library Hargrove Music Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-2623 Email: [email protected] URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/music_library_archives © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. ARCHIVES SEEGER 1 1 Inventory of the Charles Seeger musical compositions and published research articles, 1908-1978 Collection number: ARCHIVES SEEGER 1 The Music Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information Hargrove Music Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-2623 Email: [email protected] URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/music_library_archives Processed by: The Music Library staff Encoded by: Xiuzhi Zhou © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Charles Seeger musical compositions and published research articles, Date (inclusive): 1908-1978 Collection number: ARCHIVES SEEGER 1 Creator: Seeger, Charles, 1886-1979 Extent: Number of containers: 4 boxes (63 items) Repository: The Music Library Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Shelf location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the Library's online catalog. Language: English. Donor Professor Bonnie Wade, chairman of the Music Department. Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of the Music Library. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Charles Seeger musical compositions and published research articles, ARCHIVES SEEGER 1, The Music Library, University of California, Berkeley. -

2013 R&B Festival at Metrotech Kicks Off A

2013 R&B Festival at MetroTech kicks off a summer of free live funk, dub, Afrobeat, brass band, West African, blues, and soul Thursdays (except Avery*Sunshine on Wednesday, July 3) Jun 6—Aug 8, 12—2pm MetroTech Commons June 6: Mint Condition June 13: Bobby Rush June 20: Kaleta & ZoZo Afrobeat June 27: Stooges Brass Band July 3: Avery*Sunshine July 11: Sly & Robbie featuring Bunny Rugs from Third World July 18: Fatoumata Diawara July 25: Bombino Aug 1: Sheila E. Aug 8: Shuggie Otis First New York Partners is the Presenting Sponsor of the 2013 R&B Festival at MetroTech. Brooklyn, NY/May 2, 2012—BAM announces the 2013 BAM R&B Festival at MetroTech. Now in its 19th year, the festival continues to feature R&B legends alongside vibrant and groundbreaking newcomers with 10 free outdoor concerts from June 6 through August 8. Event producer Danny Kapilian said, "With this year's 19th annual BAM R&B Festival, the total number of artists who have graced our stage reaches 202! (Booker T & the MG's remains the only act to perform twice). Classic stars making their MetroTech debuts in 2013 include the Twin City funk/pop legends Mint Condition (opening on June 6th), Chicago's timeless star Bobby Rush bandleader, percussionist, and Prince alumnus Sheila E and Mr. "Strawberry Letter 23" himself Shuggie Otis (closing on August 8th). New Orleans funk returns with the fabulous Stooges Brass Band, and contemporary soul diva Avery*Sunshine spreads her love and music on July 3rd (the season's only Wednesday afternoon concert, due to the holiday). -

AMS/SMT Indianapolis 2010: Abstracts

AMS_2010_full.pdf 1 9/11/2010 5:08:41 PM ASHGATE New Music Titles from Ashgate Publishing… Adrian Willaert and the Theory Music, Sound, and Silence of Interval Affect in Buffy the Vampire Slayer The Musica nova Madrigals and the Edited by Paul Attinello, Janet K. Halfyard Novel Theories of Zarlino and Vicentino and Vanessa Knights Timothy R. McKinney Ashgate Popular and Folk Music Series Includes 69 music examples Includes 20 b&w illustrations Aug 2010. 336 pgs. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6509-0 Feb 2010. 304 pgs. Pbk. 978-0-7546-6042-2 Changing the System: The Musical Ear: The Music of Christian Wolff Oral Tradition in the USA Edited by Stephen Chase and Philip Thomas Anne Dhu McLucas Includes 1 b&w illustration and 49 musical examples SEMPRE Studies in The Psychology of Music Aug 2010. 284 pgs. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6680-6 Includes 1 b&w illustration, 2 music examples and a CD Mar 2010. 218 pgs. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6396-6 Shostakovich in Dialogue Form, Imagery and Ideas in Quartets 1–7 Music and the Modern Judith Kuhn Condition: Investigating Includes 32 b&w illustrations and 99 musical examples Feb 2010. 314 pgs. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6406-2 the Boundaries Ljubica Ilic Harrison Birtwistle: Oct 2010. 140 pgs. Hbk. 978-1-4094-0761-4 C The Mask of Orpheus New Perspectives M Jonathan Cross Landmarks in Music Since 1950 on Marc-Antoine Charpentier Includes 10 b&w illustrations and 12 music examples Edited by Shirley Thompson Y Dec 2009. 196 pgs. Hbk. 978-0-7546-5383-7 Includes 2 color and 20 b&w illustrations and 37 music examples Apr 2010. -

2004 Annual Report

2004 Annual Report Mission Statement Remembering Balanchine Peter Martins - Ballet Master in Chief Meeting the Demands Barry S. Friedberg - Chairman New York City Ballet Artistic NYCB Orchestra Board of Directors Advisory Board Balanchine 100: The Centennial Celebration 2003-2004 The Centennial Celebration Commences & Bringing Balanchine Back-Return to Russia On to Copenhagen & Winter Season-Heritage A Warm Welcome in the Nation's Capital & Spring Season-Vision Exhibitions, Publications, Films, and Lectures New York City Ballet Archive New York Choreographic Institute Education and Outreach Reaching New Audiences through Expanded Internet Technology & Salute to Our Volunteers The Campaign for New York City Ballet Statements of Financial Position Statements of Activities Statements of Cash Flows Footnotes Independent Auditors' Report All photographs by © Paul Kolnik unless otherwise indicated. The photographs in this annual report depict choreography copyrighted by the choreographer. Use of this annual report does not convey the right to reproduce the choreography, sets or costumes depicted herein. Inquiries regarding the choreography of George Balanchine shall be made to: The George Balanchine Trust 20 Lincoln Center New York, NY 10023 Mission Statement George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein formed New York City Ballet with the goal of producing and performing a new ballet repertory that would reimagine the principles of classical dance. Under the leadership of Ballet Master in Chief Peter Martins, the Company remains dedicated to their vision as it pursues two primary objectives: 1. to preserve the ballets, dance aesthetic, and standards of excellence created and established by its founders; and 2. to develop new work that draws on the creative talents of contemporary choreographers and composers, and speaks to the time in which it is made.