Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol2 Case History English(1-206)

Renewal & Upgrading of Hydropower Plants IEA Hydro Technical Report _______________________________________ Volume 2: Case Histories Report March 2016 IEA Hydropower Agreement: Annex XI AUSTRALIA USA Table of contents㸦Volume 2㸧 ࠙Japanࠚ Jp. 1 : Houri #2 (Miyazaki Prefecture) P 1 㹼 P 5ۑ Jp. 2 : Kikka (Kumamoto Prefecture) P 6 㹼 P 10ۑ Jp. 3 : Hidaka River System (Hokkaido Electric Power Company) P 11 㹼 P 19ۑ Jp. 4 : Kurobe River System (Kansai Electric Power Company) P 20 㹼 P 28ۑ Jp. 5 : Kiso River System (Kansai Electric Power Company) P 29 㹼 P 37ۑ Jp. 6 : Ontake (Kansai Electric Power Company) P 38 㹼 P 46ۑ Jp. 7 : Shin-Kuronagi (Kansai Electric Power Company) P 47 㹼 P 52ۑ Jp. 8 : Okutataragi (Kansai Electric Power Company) P 53 㹼 P 63ۑ Jp. 9 : Okuyoshino / Asahi Dam (Kansai Electric Power Company) P 64 㹼 P 72ۑ Jp.10 : Shin-Takatsuo (Kansai Electric Power Company) P 73 㹼 P 78ۑ Jp.11 : Yamasubaru , Saigo (Kyushu Electric Power Company) P 79 㹼 P 86ۑ Jp.12 : Nishiyoshino #1,#2(Electric Power Development Company) P 87 㹼 P 99ۑ Jp.13 : Shin-Nogawa (Yamagata Prefecture) P100 㹼 P108ۑ Jp.14 : Shiroyama (Kanagawa Prefecture) P109 㹼 P114ۑ Jp.15 : Toyomi (Tohoku Electric Power Company) P115 㹼 P123ۑ Jp.16 : Tsuchimurokawa (Tokyo Electric Power Company) P124㹼 P129ۑ Jp.17 : Nishikinugawa (Tokyo Electric Power Company) P130 㹼 P138ۑ Jp.18 : Minakata (Chubu Electric Power Company) P139 㹼 P145ۑ Jp.19 : Himekawa #2 (Chubu Electric Power Company) P146 㹼 P154ۑ Jp.20 : Oguchi (Hokuriku Electric Power Company) P155 㹼 P164ۑ Jp.21 : Doi (Chugoku Electric Power Company) -

Pull-Out Map of Kanazawa Kanazawa’S Museums / Art Venues Contd

Pull-Out Map Of Kanazawa Kanazawa’s Museums / Art Venues contd... D5 HONDA MUSEUM -(Honda Zouhinkan). (all bus routes referenced from JR Kanazawa Station unless noted) Displays the Honda family collection. The first Lord Honda was secretary to the ruling Maeda clan and his family heirlooms include some truly fascinating stuff ranging from instruments of war to candy boxes and sake cups. Fee: 500-yen Open: 9:00-16:30 TEL: (076) 261-0500 / 3-1 Dewa- machi. Bus: (Get off at Kencho-mae) Bus #: 10-11-12-15-25-33-50-53-70-71-73-75-80-84-85-90. Places Of Interest In Kanazawa D5 NAKAMURA MEMORIAL MUSEUM -(Nakamura Kinen Bijutsukan) Smaller museum whose highlight is an intricate display of tea ceremony tools and utensils. Ticket includes tea and sweets in the tearoom. Fee: 300-yen Open: 9:00-16:30 (closed Thurs.) TEL: (076) 221-0751 / 3-2-29 Honda-machi. Map Ref. Bus: (Get off at Honda-machi). Bus #: 18-19-91 D6 KENROKU-EN GARDEN One of Japan’s Three Sublime Gardens dating back to the 17th Century. The best times to visit: before 11 AM and after 3 PM – avoid the throng. Enjoy the serene ponds and old-world teahouses. Don’t miss the sprawling Seison Kaku Villa within the castle grounds, (a separate th -- KANAZAWA CITIZEN’S ART CENTRE – (Geijutsu Mura) Not on map but an excellent facility for modern and classical art work exhibitions, regular fee must be paid). This is an opulent, original home beautifully built in1863 by the 13 Lord Maeda for his mother.The soothing tsukushi garden here live drama and music performances. -

Geography & Climate

Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE A country of diverse topography and climate characterized by peninsulas and inlets and Geography offshore islands (like the Goto archipelago and the islands of Tsushima and Iki, which are part of that prefecture). There are also A Pacific Island Country accidented areas of the coast with many Japan is an island country forming an arc in inlets and steep cliffs caused by the the Pacific Ocean to the east of the Asian submersion of part of the former coastline due continent. The land comprises four large to changes in the Earth’s crust. islands named (in decreasing order of size) A warm ocean current known as the Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku, Kuroshio (or Japan Current) flows together with many smaller islands. The northeastward along the southern part of the Pacific Ocean lies to the east while the Sea of Japanese archipelago, and a branch of it, Japan and the East China Sea separate known as the Tsushima Current, flows into Japan from the Asian continent. the Sea of Japan along the west side of the In terms of latitude, Japan coincides country. From the north, a cold current known approximately with the Mediterranean Sea as the Oyashio (or Chishima Current) flows and with the city of Los Angeles in North south along Japan’s east coast, and a branch America. Paris and London have latitudes of it, called the Liman Current, enters the Sea somewhat to the north of the northern tip of of Japan from the north. The mixing of these Hokkaido. -

Gaudenz Domenig

Gaudenz DOMENIG * Land of the Gods Beyond the Boundary Ritual Landtaking and the Horizontal World View** 1. Introduction The idea that land to be taken into possession for dwelling or agriculture is already inhabited by beings of another kind may be one the oldest beliefs that in the course of history have conditioned religious attitudes towards space. Where the raising of a building, the founding of a settlement or city, or the clearing of a wilderness for cultivation was accompanied by ritual, one of the ritual acts usually was the exorcising of local beings supposed to have been dwelling there before. It is often assumed that this particular ritual act served the sole purpose of driving the local spirits out of the new human domain. Consequently, the result of the ritual performance is commonly believed to have been a situation where the castaways were thought to carry on beyond the land’s boundary, in an outer space that would surround the occupied land as a kind of “chaos.” Mircea Eliade has expressed this idea as follows: One of the characteristics of traditional societies is the opposition they take for granted between the territory they inhabit and the unknown and indeterminate space that surrounds it. Their territory is the “world” (more precisely, “our world”), the cosmos; the rest is no longer cosmos but a kind of “other world,” a foreign, chaotic space inhabited by ghosts, demons, and “foreigners” (who are assimilated to the demons and the souls of the dead). (Eliade 1987: 29) * MSc ETH (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology), Zürich. -

Flood Loss Model Model

GIROJ FloodGIROJ Loss Flood Loss Model Model General Insurance Rating Organization of Japan 2 Overview of Our Flood Loss Model GIROJ flood loss model includes three sub-models. Floods Modelling Estimate the loss using a flood simulation for calculating Riverine flooding*1 flooded areas and flood levels Less frequent (River Flood Engineering Model) and large- scale disasters Estimate the loss using a storm surge flood simulation for Storm surge*2 calculating flooded areas and flood levels (Storm Surge Flood Engineering Model) Estimate the loss using a statistical method for estimating the Ordinarily Other precipitation probability distribution of the number of affected buildings and occurring disasters related events loss ratio (Statistical Flood Model) *1 Floods that occur when water overflows a river bank or a river bank is breached. *2 Floods that occur when water overflows a bank or a bank is breached due to an approaching typhoon or large low-pressure system and a resulting rise in sea level in coastal region. 3 Overview of River Flood Engineering Model 1. Estimate Flooded Areas and Flood Levels Set rainfall data Flood simulation Calculate flooded areas and flood levels 2. Estimate Losses Calculate the loss ratio for each district per town Estimate losses 4 River Flood Engineering Model: Estimate targets Estimate targets are 109 Class A rivers. 【Hokkaido region】 Teshio River, Shokotsu River, Yubetsu River, Tokoro River, 【Hokuriku region】 Abashiri River, Rumoi River, Arakawa River, Agano River, Ishikari River, Shiribetsu River, Shinano -

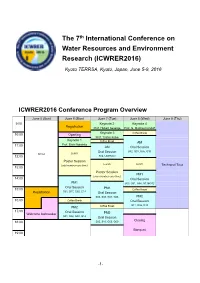

The 7Th International Conference on Water Resources and Environment

th The 7 International Conference on Water Resources and Environment Research (ICWRER2016) Kyoto TERRSA, Kyoto, Japan, June 5-9, 2016 ICWRER2016 Conference Program Overview June 5 (Sun) June 6 (Mon) June 7 (Tue) June 8 (Wed) June 9 (Thu) 9:00 Keynote 2 Keynote 4 Registration Prof. Hubert Savenije Prof. G. Mathias Kondolf Keynote 3 Coffee Break 10:00 Opening Prof. Toshio Koike Keynote 1 Coffee Break AM 11:00 Prof. Eiichi Nakakita AM Oral Session Oral Session S02, G01, G05, G10 Arrival Lunch 12:00 S02, UNESCO Poster Session Lunch (odd number core time) Lunch Technical Tour 13:00 Poster Session PM1 (even number core time) 14:00 Oral Session PM1 S03, G01, G04, G11&G12 Oral Session 15:00 PM1 Coffee Break Registration S01, S07, G02, G14 Oral Session S02, S05, G07, G08 PM2 16:00 Coffee Break Oral Session S11, G06, G13 PM2 Coffee Break 17:00 Oral Session Welcome Icebreaker PM2 S01, S06, G02, G14 Oral Session Closing 18:00 S02, S10, G03, G09 Banquet 19:00 -1- ICWRER2016 Session & Room Information Room Ⅰ Room Ⅱ Room Ⅲ Room Ⅳ Keynote 1 K1 Prof. Eiichi Nakakita S07: Optimum Management of G02: GIS and Remote Sensing in S01: Climate Change Impacts G14: Sustainable Water Resources June 6 PM1 Water Resources and Hydrology and Water on Natural Hazards (1) Management (1) (Mon) Environmental Systems Resources (1) G02: GIS and Remote Sensing in S01: Climate Change Impacts G14: Sustainable Water Resources PM2 S06: Isotope Hydrology Hydrology and Water on Natural Hazards (2) Management (2) Resources (2) Keynote 2 K2 Prof. Hubert Savenije Keynote 3 K3 Prof. -

The Moon Bear As a Symbol of Yama Its Significance in the Folklore of Upland Hunting in Japan

Catherine Knight Independent Scholar The Moon Bear as a Symbol of Yama Its Significance in the Folklore of Upland Hunting in Japan The Asiatic black bear, or “moon bear,” has inhabited Japan since pre- historic times, and is the largest animal to have roamed Honshū, Shikoku, and Kyūshū since mega-fauna became extinct on the Japanese archipelago after the last glacial period. Even so, it features only rarely in the folklore, literature, and arts of Japan’s mainstream culture. Its relative invisibility in the dominant lowland agrarian-based culture of Japan contrasts markedly with its cultural significance in many upland regions where subsistence lifestyles based on hunting, gathering, and beliefs centered on the mountain deity (yama no kami) have persisted until recently. This article explores the significance of the bear in the upland regions of Japan, particularly as it is manifested in the folklore of communities centered on hunting, such as those of the matagi, and attempts to explain why the bear, and folklore focused on the bear, is largely ignored in mainstream Japanese culture. keywords: Tsukinowaguma—moon bear—matagi hunters—yama no kami—upland communities—folklore Asian Ethnology Volume 67, Number 1 • 2008, 79–101 © Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture nimals are common motifs in Japanese folklore and folk religion. Of the Amammals, there is a wealth of folklore concerning the fox, raccoon dog (tanuki), and wolf, for example. The fox is regarded as sacred, and is inextricably associated with inari, originally one of the deities of cereals and a central deity in Japanese folk religion. It has therefore become closely connected with rice agri- culture and thus is an animal symbol central to Japan’s agrarian culture. -

Copyright by Peter David Siegenthaler 2004

Copyright by Peter David Siegenthaler 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Peter David Siegenthaler certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Looking to the Past, Looking to the Future: The Localization of Japanese Historic Preservation, 1950–1975 Committee: Susan Napier, Supervisor Jordan Sand Patricia Maclachlan John Traphagan Christopher Long Looking to the Past, Looking to the Future: The Localization of Japanese Historic Preservation, 1950–1975 by Peter David Siegenthaler, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2004 Dedication To Karin, who was always there when it mattered most, and to Katherine and Alexander, why it all mattered in the first place Acknowledgements I have accumulated many more debts in the course of this project than I can begin to settle here; I can only hope that a gift of recognition will convey some of my gratitude for all the help I have received. I would like to thank primarily the members of my committee, Susan Napier, Patricia Maclachlan, Jordan Sand, Chris Long, and John Traphagan, who stayed with me through all the twists and turns of the project. Their significant scholarly contributions aside, I owe each of them a debt for his or her patience alone. Friends and contacts in Japan, Austin, and elsewhere gave guidance and assistance, both tangible and spiritual, as I sought to think about approaches broader than the immediate issues of the work, to make connections at various sites, and to locate materials for the research. -

Japanese Folk Tale

The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale Copublished with Asian Folklore Studies YANAGITA KUNIO (1875 -1962) The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale Translated and Edited by FANNY HAGIN MAYER INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington This volume is a translation of Nihon mukashibanashi meii, compiled under the supervision of Yanagita Kunio and edited by Nihon Hoso Kyokai. Tokyo: Nihon Hoso Shuppan Kyokai, 1948. This book has been produced from camera-ready copy provided by ASIAN FOLKLORE STUDIES, Nanzan University, Nagoya, japan. © All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nihon mukashibanashi meii. English. The Yanagita Kunio guide to the japanese folk tale. "Translation of Nihon mukashibanashi meii, compiled under the supervision of Yanagita Kunio and edited by Nihon Hoso Kyokai." T.p. verso. "This book has been produced from camera-ready copy provided by Asian Folklore Studies, Nanzan University, Nagoya,japan."-T.p. verso. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Tales-japan-History and criticism. I. Yanagita, Kunio, 1875-1962. II. Mayer, Fanny Hagin, 1899- III. Nihon Hoso Kyokai. IV. Title. GR340.N52213 1986 398.2'0952 85-45291 ISBN 0-253-36812-X 2 3 4 5 90 89 88 87 86 Contents Preface vii Translator's Notes xiv Acknowledgements xvii About Folk Tales by Yanagita Kunio xix PART ONE Folk Tales in Complete Form Chapter 1. -

Product Catalogue 2020

We Bridge Over Borders and Generations with the Treasures of Japan Catalogue of Authentic Japanese foods & drinks Japonte Ltd. Authentic Japanese foods & drinks RICE 3 Koshihikari TEA 4 Kamairicha, Organic Matcha, Organic Hojicha NORI 7 Premium Nori SHIITAKE 8 Forest-grown Shiitake DASHI 9 Honkarebushi IPPON-DZURI KUZU 10 Premium Honkuzu AME 11 Rice Syrup SEASONING 12 Fermented Nori Seasoning 10 Whole-grains Miso, Dried Ten grain miso FISH 15 Golden Anago DRINK 16 Sake, Kuma Shochu, Awamori Japonte Ltd. L14, Hibiya Central Building, 1-2-9 Nishi Shimbashi Minato-ku, Tokyo [email protected] Kurobe Koshihikari 黒部産こしひかり The Kurobe River fan where the melting snow waters from the Tateyama mountain range flows is a great area for cultivating safe delicious rice. Our Koshihikari rice is carefully cultivated with significant reduction of agro-chemical usage. Balanced soil making has been carried out by utilizing composts of ripened rice hulls and so on, to develop the environmentaly sustainable processes continuously. Kurobe Item NET Shelf life White rice 10 kg 1 year Brown rice 10 kg 1 year Black rice 1 kg 1 year Japonte Ltd. L14, Hibiya Central Building, 1-2-9 Nishi Shimbashi Minato-ku, Tokyo [email protected] Ureshino Kamairi Cha うれしの釜炒り茶 A clear, golden-hued Japanese tea with a light, refreshing fragrance and faint sweetness. Brought to you by producers that have practiced organic farming for many generations in Ureshino - a place famous in the history of Japanese tea for its production of brand-name teas. Tea leaves are prepared with the utmost care, through the traditional Kamairi method that came to Japan through China 500 years ago. -

The Body As a Mode of Conceptualization in the Kojiki Cosmogony1)

47 The Body as a Mode of Conceptualization in the Kojiki Cosmogony1) ロ ー ベ ルト・ヴィットカン プ WITTKAMP, Robert F. Although the Kojiki was submitted to the court in 712, it is not mentioned in the Shoku Nihongi, which contains the official history from 697 till 791. This paper is based on the assumption that intrinsic reasons were at least partially at work and will address the problem by subjecting the conceptualization of the text to closer review. “Conceptu- alization” refers to kōsō 構想(concept, idea, design of a text), an important concept used in text-oriented Kojiki research to describe the selections and restrictions of words, phrases or stories and their arrangement in a coherent and closed text. The examina- tion shows that mi 身(“body”) belongs to the keywords in Kojiki myths, and another assumption is that the involvement of mi is a unique feature of Kojiki text design which distinguishes the work from the Nihon Shoki myths – one, which possibly overshot the mark. キーワード:日本神話(Japanese myths)、古事記(Kojiki)、構想(conceptualiza- tion)、身(body)、上代史(pre-Heian history) 1) This paper is based on a talk given at a conference at Hamburg University( Arbeitskreis vormoderne Literatur Japans, 2017, June 29th to July 2nd). 48 According to its preface the Kojiki is an official chronicle which was commissioned by Genmei Tenno in 711 and submitted some months later in 712. But why is it not mentioned in the Shoku Nihongi, the second of the six Japanese histories( rikkokushi 六国史) of the Nara and Heian period, which contains the official history from 697 till 791 and was submitted in 797? There are many possible explanations, ranging from a forged Kojiki preface to the simple fact that other texts of the eighth century are not mentioned either. -

Eighth Century Classics Japanese G9040 (Spring 2009)

Graduate Seminar on Premodern Japanese Literature: Eighth Century Classics Japanese G9040 (Spring 2009) W 4:10-6:00, 716A Hamilton David Lurie (212-854-5034, [email protected]) Office Hours: M 3:00-4:30 and W 11:00-12:30, 500A Kent Hall Course Rationale: A non-systematic overview of Nara period classics, with some attention to their reception in the medieval, early modern, and modern periods, this class is intended for PhD. and advanced M.A. students in Japanese literature, history, and related fields. The emphasis will be on following up particular themes that cut across multiple works, for their own intrinsic interest, but also because they allow comparative insights into the distinctive characteristics of the Kojiki, Nihon shoki, Fudoki, and Man’yôshû. Requirements: 1) Consistent attendance and participation, including in-class reading and translation of selected passages 2) Occasional presentations on selected secondary sources 3) A short final project (around 10 pages), topic subject to instructor’s approval: either an interpretative essay concerning one or more of the primary sources considered this semester, or an annotated translation of a passage from one of them or from a reasonably closely connected work. Schedule: 1) 21 Jan. Introduction: Course Objectives and Materials As our basic texts, we will rely on the Shinpen Nihon koten bungaku zenshû (SNKBZ) editions of the Kojiki, Nihon shoki, Fudoki, and Man’yôshû. These will be supplemented by various other modern commentaries, among the most important of which are: Kojiki: Shinchô Nihon koten shûsei (SNKS) and Nihon shisô taikei (NST) Nihon shoki and Fudoki: Nihon koten bungaku taikei (NKBT) Man’yôshû: Shin Nihon koten bungaku taikei (SNKBT) and Waka bungaku taikei (WBT).1 Besides the Nihon koten bungaku daijiten, Kokushi daijiten, and Nihon kokugo daijiten, essential references include: Jidaibetsu Kokugo daijiten Jôdaihen, Jôdai bungaku kenkyû jiten, Man’yô kotoba jiten, Nihon shinwa jiten, and Jôdai setsuwa jiten.