History of Learning and Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Problem Solving and Learning

Science Watch Problem Solving and Learning John R. Anderson Newell and Simon (1972) provided a framework for un- computer simulation of human thought and was basically derstanding problem solving that can provide the needed unconnected to research in animal and human learning. bridge between learning and performance. Their analysis Research on human learning and research on prob- of means-ends problem solving can be viewed as a general lem solving are finally meeting in the current research characterization of the structure of human cognition. on the acquisition of cognitive skills (Anderson, 1981; However, this framework needs to be elaborated with a Chi, Glaser, & Farr, 1988; Van Lehn, 1989). Given nearly strength concept to account for variability in problem- a century of mutual neglect, the concepts from the two solving behavior and improvement in problem-solving skill fields are ill prepared to relate to each other. I will argue with practice. The ACT* theory (Anderson, 1983) is such in this article that research on human problem solving an elaborated theory that can account for many of the would have been more profitable had it attempted to in- results about the acquisition of problem-solving skills. Its corporate ideas from learning theory. Even more so, re- central concept is the production rule, which plays an search on learning would have borne more fruit had analogous role to the stimulus-response bond in earlier Thorndike not cast out problem solving. learning theories. The theory has provided a basis for con- This article will review the basic conception of prob- structing intelligent computer-based tutoring systems for lem solving that is the legacy of the Newell and Simon the instruction of academic problem-solving skills. -

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

Teacher Training: Learning to Be Instigators of Thought™ Through a Process Aligned with Inspired Teaching's Educational Phil

Transforming education through innovation teacher training Teacher Training: Learning to be Instigators of Thought™ Through a process aligned with Inspired Teaching’s educational philosophy – which engages participants intellectually, physically, and emotionally - Inspired Teaching trains teachers to design and implement rigorous, student-centered lessons and activities that meet student needs and academic standards, including the Common Core State Standards. Like the teaching process itself, our teacher training is complex and allows for customization to meet the specific needs of each teacher. This audience-sensitivity creates a permanent shift in teachers’ thinking about their jobs and is one of the key reasons our process is so effective. Inspired Teaching’s Five Step Process for Teacher Education Each teacher navigates the following process: Step 1. Analyze and deepen my understanding of the ways I learn through a rigorous examination of the teaching and learning process, including my including my own experiences as a child and adult learner. Step 2. Articulate and defend my philosophy of teaching and learning , including what I believe about children. Challenge myself to listen to and consider other points of view and to find room in my philosophy for an appreciation of children's natural curiosity and innate desire to learn. Step 3. Make the connection to classroom practice , analyzing my current instructional strategies and whether they support my philosophy, so that I can explore and develop new ways to make sure what I do in the classroom matches my philosophy of teaching and learning. Step 4. Build the skills of effective teachers , including active listening, asking questions that will spark students' intellect and imaginations, observing to assess for student understanding, and communicating effectively. -

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky and Robert A. Bjork Introduction Memory has been of interest to scholars and laypeople alike for over 2,000 years. In a rather gruesome example from antiquity, Cicero tells the story of Simonides (557– 468 BC), who discovered the method of loci, which is a powerful mental mnemonic for enhancing one’s memory. Simonides was at a banquet of a nobleman, Scopas. To honor him, Simonides sang a poem, but to Scopas’s chagrin, the poem also honored two young men, Castor and Pollux. Being upset, Scopas told Simonides that he was to receive only half his wage. Simonides was later called from the banquet, and legend has it that the banquet room collapsed, and all those inside were crushed. To help bereaved families identify the victims, Simonides reportedly was able to name every- one according to the place where they sat at the table, which gave him the idea that order brings strength to our memories and that to employ this ability people “should choose localities, then form mental images of things they wanted to store in their memory, and place these in the localities” (Cicero, 2001). Tis example highlights an early discovery that has had important applied impli- cations for improving the functioning of memory (see, e.g., Yates, 1997). Memory theory was soon to follow. Aristotle (385–322 BC) claimed that memory arises from three processes: Events are associated (1) through their relative similarity or (2) rela- tive dissimilarity and (3) when they co-occur together in space and time. -

Types of Memory and Models of Memory

Inf1: Intro to Cognive Science Types of memory and models of memory Alyssa Alcorn, Helen Pain and Henry Thompson March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 1 1. In the lecture today A review of short-term memory, and how much stuff fits in there anyway 1. Whether or not the number 7 is magic 2. Working memory 3. The Baddeley-Hitch model of memory hEp://www.cartoonstock.com/directory/s/ short_term_memory.asp March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 2 2. Review of Short-Term Memory (STM) Short-term memory (STM) is responsible for storing small amounts of material over short periods of Nme A short Nme really means a SHORT Nme-- up to several seconds. Anything remembered for longer than this Nme is classified as long-term memory and involves different systems and processes. !!! Note that this is different that what we mean mean by short- term memory in everyday speech. If someone cannot remember what you told them five minutes ago, this is actually a problem with long-term memory. While much STM research discusses verbal or visuo-spaal informaon, the disNncNon of short vs. long-term applies to other types of sNmuli as well. 3/21/12 Intro to Cognitive Science 3 3. Memory span and magic numbers Amount of informaon varies with individual’s memory span = longest number of items (e.g. digits) that can be immediately repeated back in correct order. Classic research by George Miller (1956) described the apparent limits of short-term memory span in one of the most-cited papers in all of psychology. -

Handbook of Metamemory and Memory Evolution of Metacognition

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 29 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Handbook of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky, Robert A. Bjork Evolution of Metacognition Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203805503.ch3 Janet Metcalfe Published online on: 28 May 2008 How to cite :- Janet Metcalfe. 28 May 2008, Evolution of Metacognition from: Handbook of Metamemory and Memory Routledge Accessed on: 29 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203805503.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Evolution of Metacognition Janet Metcalfe Introduction The importance of metacognition, in the evolution of human consciousness, has been emphasized by thinkers going back hundreds of years. While it is clear that people have metacognition, even when it is strictly defined as it is here, whether any other animals share this capability is the topic of this chapter. -

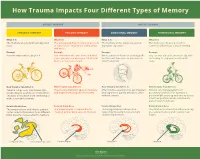

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Cognitive Psychology

COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY PSYCH 126 Acknowledgements College of the Canyons would like to extend appreciation to the following people and organizations for allowing this textbook to be created: California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office Chancellor Diane Van Hook Santa Clarita Community College District College of the Canyons Distance Learning Office In providing content for this textbook, the following professionals were invaluable: Mehgan Andrade, who was the major contributor and compiler of this work and Neil Walker, without whose help the book could not have been completed. Special Thank You to Trudi Radtke for editing, formatting, readability, and aesthetics. The contents of this textbook were developed under the Title V grant from the Department of Education (Award #P031S140092). However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. Unless otherwise noted, the content in this textbook is licensed under CC BY 4.0 Table of Contents Psychology .................................................................................................................................................... 1 126 ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 1 - History of Cognitive Psychology ............................................................................................. 7 Definition of Cognitive Psychology -

The Nature of Learning and Memory

Arlo Clark-Foos, Ph.D. 2 October 2017 1 • Life Without Memory (Clive Wearing) – Video Clive’s Diary “10:08 a.m.: Now I am superlatively awake. First time aware for years.” “10:13 a.m.: Now I am overwhelmingly awake.” “10:28 a.m.: Actually I am now the first time awake for years.” 10/2/2017 12:41 PM 2 • Genes determine the possible range. • Reflex actions, simple behaviors – Knee-jerk, swallow, suck, grip John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner 2 October 2017 3 • Experience (and memory of it) determines our individual differences and allows us to improve upon initial behaviors and reflexes. 2 October 2017 4 • How well can you read these sentences? The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. Pack my box with five dozen liquor jugs. 2 October 2017 5 • Context and Expectations Group 1 Group 2 2 October 2017 6 Bugelski & Alampay (1961) 2 October 2017 7 Jastrow (1899) 2 October 2017 8 Kremen (2010) 2 October 2017 9 2 October 2017 10 2 October 2017 11 • Introspection, Logic, & Philosophy • Plato’s Aviary metaphor 2 October 2017 12 “other animals (as well as man) have memory, but … none … except man, shares in the faculty of recollection” • Observation and Data Theories • Contiguity, Frequency, Similarity • All knowledge is innate, • Memory The Republic – Replication of sensory perception – Passive re-perception • Familiarity? • Intuition and Logic • Reminiscence – Replaying an entire experience – Temporal contiguity • Recollection? 2 October 2017 13 Mind Body Cogito ergo sum Stimulus, Response (reflex arc) (Descartes, 1637) Like a machine/clock Animal “Spirits” flow Knowledge is mostly innate 2 October 2017 14 • Absolute Power of the Monarchy – Isaac Newton’s Light and Robert Boyle’s chemicals • Associationism (Green, Bitter/Sour vs. -

Memory-Modulation: Self-Improvement Or Self-Depletion?

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY published: 05 April 2018 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00469 Memory-Modulation: Self-Improvement or Self-Depletion? Andrea Lavazza* Neuroethics, Centro Universitario Internazionale, Arezzo, Italy Autobiographical memory is fundamental to the process of self-construction. Therefore, the possibility of modifying autobiographical memories, in particular with memory-modulation and memory-erasing, is a very important topic both from the theoretical and from the practical point of view. The aim of this paper is to illustrate the state of the art of some of the most promising areas of memory-modulation and memory-erasing, considering how they can affect the self and the overall balance of the “self and autobiographical memory” system. Indeed, different conceptualizations of the self and of personal identity in relation to autobiographical memory are what makes memory-modulation and memory-erasing more or less desirable. Because of the current limitations (both practical and ethical) to interventions on memory, I can Edited by: only sketch some hypotheses. However, it can be argued that the choice to mitigate Rossella Guerini, painful memories (or edit memories for other reasons) is somehow problematic, from an Università degli Studi Roma Tre, Italy ethical point of view, according to some of the theories of the self and personal identity Reviewed by: in relation to autobiographical memory, in particular for the so-called narrative theories Tillmann Vierkant, University of Edinburgh, of personal identity, chosen here as the main case of study. Other conceptualizations of United Kingdom the “self and autobiographical memory” system, namely the constructivist theories, do Antonella Marchetti, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, not have this sort of critical concerns. -

Cognition, Affect, and Learning —The Role of Emotions in Learning

How People Learn: Cognition, Affect, and Learning —The Role of Emotions in Learning Barry Kort Ph.D. and Robert Reilly Ed.D. {kort, reilly}@media.mit.edu formerly MIT Media Lab Draft as of date January 2, 2019 Learning is the quintessential emotional experience. Our species, Homo Sapiens, are the beings who think. We are also the beings who learn, and the beings who simultaneously experience a rich spectrum of affective emotional states, including a selected suite of emotional states specifically and directly related to learning. This proposal reviews previously published research and theoretical models relating emotions to learning and cognition and presents ideas and proposals for extending that research and reducing it to practice. Our perspective The concept of affect in learning (i.e., emotions in learning) is the same pedagogy applied by an athletic coach at a sporting event. A coach recognizes the affective state of an athlete, and, for example, exhorts that athlete toward increased performance (e.g., raises the level of enthusiasm), or, redirects a frustrated athlete to a productive affective state (e.g., instills confidence, or pride). A coach recognizes that an athlete’s affective state is a critical factor during performance; and, when appropriate, a coach will intervene with a meaningful strategy or tactic. Athletic coaches are skilled at recognizing affective states and intervening appropriately. Educators can have the same impact on a learner by understanding a learner’s affective state and intervening with appropriate strategies or tactics that will meaningfully manage and guide a person’s learning journey. There are several learning theories and a great deal of neuroscience/affective research. -

An Introduction to Late British Associationism and Its Context This Is a Story About Philosophy. Or About Science

Chapter 1: An Introduction to Late British Associationism and Its Context This is a story about philosophy. Or about science. Or about philosophy transforming into science. Or about science and philosophy, and how they are related. Or were, in a particular time and place. At least, that is the general area that the following narrative will explore, I hope with sufficient subtlety. The matter is rendered non-transparent by the fact that that the conclusions one draws with regard to such questions are, in part, matters of discretionary perspective – as I will try to demonstrate. My specific historical focus will be on the propagation of a complex intellectual tradition concerned with human sensation, perception, and mental function in early nineteenth century Britain. Not only philosophical opinion, but all aspects of British intellectual – and practical – life, were in the process of significant transformation during this time. This cultural flux further confuses recovery of the situated significance of the intellectual tradition I am investigating. The study of the mind not only was influenced by a set of broad social shifts, but it also participated in them fully as both stimulus to and recipient of changing conditions. One indication of this is simply the variety of terms used to identify the ‘philosophy of mind’ as an intellectual enterprise in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.1 But the issue goes far deeper into the fluid constitutive features of the enterprise - including associated conceptual systems, methods, intentions of practitioners, and institutional affiliations. In order to understand philosophy of mind in its time, we must put all these factors into play.